“I see you like dark lipstick too. It’s great, isn’t it? Not really like lipstick at all, more like paint,” Rose Wylie remarks as we settle down in an ante-room of the Serpentine for a chat about her new exhibition, Quack-Quack. “It’s nice to meet you. I feel as though I’ve known you for a long time from your writing.”

“The paintings remain fresh, curious and playful. Age is just a number. Imagination and curiosity are all.”

Born in 1934, Rose dresses like an art student. Grey hair cut into a bob that flops over her round Harry Potter specs. A baggy tweed jacket worn with a short skirt over tights and trainers. And, of course, the dark red lipstick. She is very friendly, very unaffected and tells me she’s enjoying her new-found fame. I remind her of Louise Bourgeois’s acerbic comment to a journalist on becoming a celebrity in her nineties that she’d been “‘ere all along”. Rose Wylie laughs. Yes, she’s been here all along, too, busily painting away. Though, as a second child, she says, she’s used to being put in her place. “So, when something finally happens that’s funny and surreal, it’s really rather nice.”

She’s been accused by detractors of making “childish” images. But that is completely to miss the point of her work. It takes a good deal of insight and self-awareness to paint this freely. Unlike a child there’s a sophisticated editing process. Decisions have to be made as to what to use and what to discard based on an instinctive sense of aesthetic “rightness”. An endless evaluation of what works and what doesn’t. The past, for her, is not so much another country but one that is continually alive and present in her work. She does not “depict” things “as they are” but rather creates memory-maps. Rosemount (Coloured), 1999, reframes some of her early childhood memories. A central black house sits surrounded by a front lawn and privet hedge, allotments and chicken run, all signposted in her loopy handwritten script. She had difficulty, she says, remembering which side of the house the chimney went. So first she had to remember which door she’d used, where the fireplace was, where the cat sat and the chickens lived. Only then, by going through all these things in her mind’s eye, could she be sure to which side of the house the chimney belonged. “What you remember,” she says, “is what was special and significant for you as a child.”

Park, Dogs and Air Raid, 2017 grew from memories of living for a short period, when she was five, close to Kensington Gardens during the Second World War. Dogs, ducks and lakes, along with the present-day Serpentine Gallery, are all thrown pell-mell into the mix, as Messerschmitts and Spitfires lour overhead in the Blitz. The Quack-Quack of the exhibition title onomatopoeically mixes the memories of ducks in the park with the more sinister sound of “ack-ack” fire. There’s an extraordinary physicality and fluidity to her paintings that remind me in their delightful irreverence of early Paula Rego or Philip Guston’s loose cartoonish shapes. I mention Cy Twombly’s use of text and she pulls a face. “Too highfalutin, too erudite,” she says.

Usually, she tells me, she paints what she sees. A work often starts with a drawing, a close observation. Though the scale may change and she may fiddle with the rules of gravity. Repetition is also important. Going at things from different perspectives and angles. It’s as if she’s grappling not to describe how things actually are, but rather what they feel like. As though the physical act of painting becomes a mechanism for remembering.

“Her use of language is anarchic and wayward. Sometimes words are misspelt or slip over the edge of a painting to remind us that they’re really a form of painterly mark-making.”

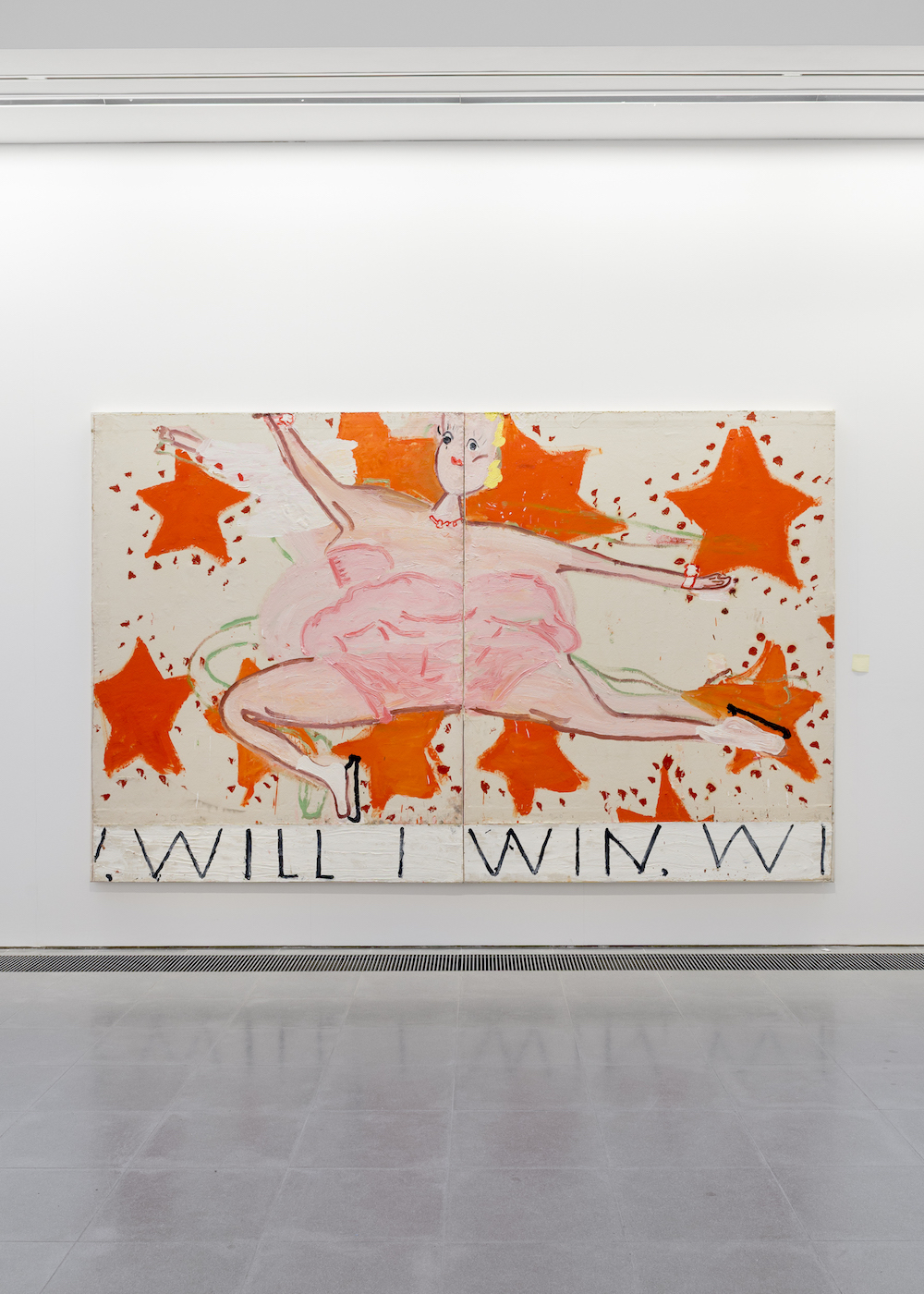

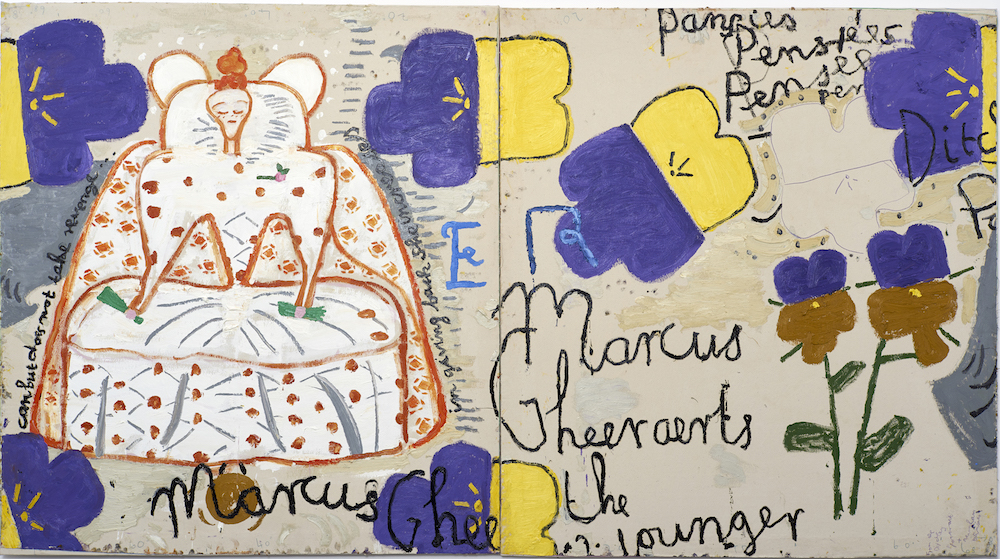

There’s a strong sense of place in her work and the text helps to detonate and to fix memories. She’s a fan of the poetry of JH Prynne, the Cambridge poet, also in his eighties, known for his powerful, dense and experimental poetry. Her use of language is anarchic and wayward. Sometimes words are misspelt or slip over the edge of a painting to remind us that they’re really a form of painterly mark-making. Her sentences are not captions but an intrinsic part of the visual whole. They may look as though they have been written by a first-year infant, but there’s a knowing physicality to them. She labels the parts of a horse in Irreverent Anatomy Drawing, 2017 in the way a child at school may label them in a biology lesson: sternum, femur, tibia, etc. Her paintings are scruffy and messy as though the one element of childhood that hasn’t abandoned her in her eighties is the ability to play.

Football—Yellow Strip, 2006, with its Eadweard Muybridge sense of sequential movement—and film are also important influences. Many of her paintings can be read like cinematic storyboards. Kill Bill (Film Notes), 2017 explores one scene from the Tarantino film from slightly different points of view. While NK (Syracuse Line Up), 2014 evokes a freeze from antiquity, Knossos, say, or an ancient wall painting from Pompeii, as well as the frames of a film. Her love of cinema is also alluded to in ER & ET, 2011, in which a generic Liz Taylor lies languidly in skimpy swimwear, surrounded by a plethora of eyes and ears. These were appropriated from the decoration on a cloak belonging to Elizabeth I and suggest that we all become voyeurs and spies when we gawp at the famous and their personal lives become public. The two parts of Pink Table Cloth (Close-Up) (Film Notes), 2013, inspired by the 2005 film Syriana directed by Stephen Gaghan, are based on a panoramic long shot and a close-up of a meeting in the desert that takes place at a table draped, rather surreally, in a pink table-cloth. As in this work, Wylie often adds sections to her paintings, another panel, say, to run along the bottom, building them into almost sculptural forms.

There’s a wonderful anarchy to her work that seems to reach back to make connections with early cave paintings—the desire for human beings to chart and explain the world—while also embracing popular culture. Above all Rose Wylie is a testament to “doing one’s own thing”. To the integrity of individual vision rather than the slavish following of fashion. She may be in her eighties but the paintings remain fresh, curious and playful. Age is just a number. Imagination and curiosity are all. And, no doubt, she will still be sporting the dark red lipstick when she is in her nineties.