Has a work of art ever moved you to tears? Or a painting stayed with you across the years? For Sutapa Biswas, that artwork is Johannes Vermeer’s Woman Reading A Letter. Painted in 1663, the scene depicts a lady standing at a window, bathed in morning light and absorbed in her correspondence. The smock she wears is cornflower blue. The moment Biswas saw it she was floored, because it reminded her, quite profoundly, of her mother.

Biswas was born in Shantiniketan, India, in 1962, but her family’s status there was fraught. Her father had been at odds with the Indian government for opposing the so-called Green Revolution. He was a Marxist, an academic, and vocal in his stance against new economic and agricultural policies. In the end, it was unsafe for him to stay in the country, and so he slipped away to the UK. “Six months later, very quietly, my mum, myself and my four siblings left too, in the middle of the night,” Biswas says. They travelled from Calcutta to Bombay and on to Genoa via the Suez Canal, and then they took a train to Calais. From there, they boarded a boat to Dover, and finally began a new life in London.

“After we arrived here, I remember watching my mother when she didn’t know I was looking, and she used to stand by the window, reading letters from home and crying,” she says. In the image that persists in her mind, her mother is wearing blue, just like in the painting, but also like sea water, rivers and tears. Later, when studying art at the University of Leeds, she would return to Vermeer, but this time she would realise she was looking at a moment in history of great Dutch colonial expansion, the very root of her family’s displacement.

“The matrilineal journey often gets left out of the grand narratives of history so this story is told through my mother’s eyes”

The symbolism of that formative journey had a powerful effect on Biswas. This year, at Kettle’s Yard, she is unveiling a newly commissioned film piece called Lumen, a fictional narrative based on the story of her mother and grandmother. “The matrilineal journey often gets left out of the grand narratives of history,” she says, “so this story is told through my mother’s eyes. What had once been India became British India, and then after Partition it became East Pakistan and finally Bangladesh, so really my family was displaced twice over. This work explores the trauma associated with that.”

Mixing archival material with new footage, the film is narrated by just one woman. Looking into the mirror she delivers her monologue with a gentle rhythm, speaking to the audience and to herself.

Biswas came of age in London’s Southall in the 1970s, amid an intense political landscape. “Anti-facist protests and riots were breaking out, and Blair Peach was killed just ahead of me going off to university,” she recalls. Later Biswas became associated with the British Black Arts movement, a political current inspired by anti-racist discourse. At Leeds, she was the first South Asian artist to study art, and the first person of colour in the department. Their lectures were heavily Eurocentric, with texts like Nikolaus Pevsner’s The Englishness of English Art on the reading list.

“From day one I began to decolonise the curriculum,” she laughs. “My father instilled a real sense of self-worth in me, and so I was able to go there and challenge my tutors. I think I was really sensitised to the fact that in order to shift the dialogue, I needed to make art that brought together iconography that fell outside of the usual reference points.”

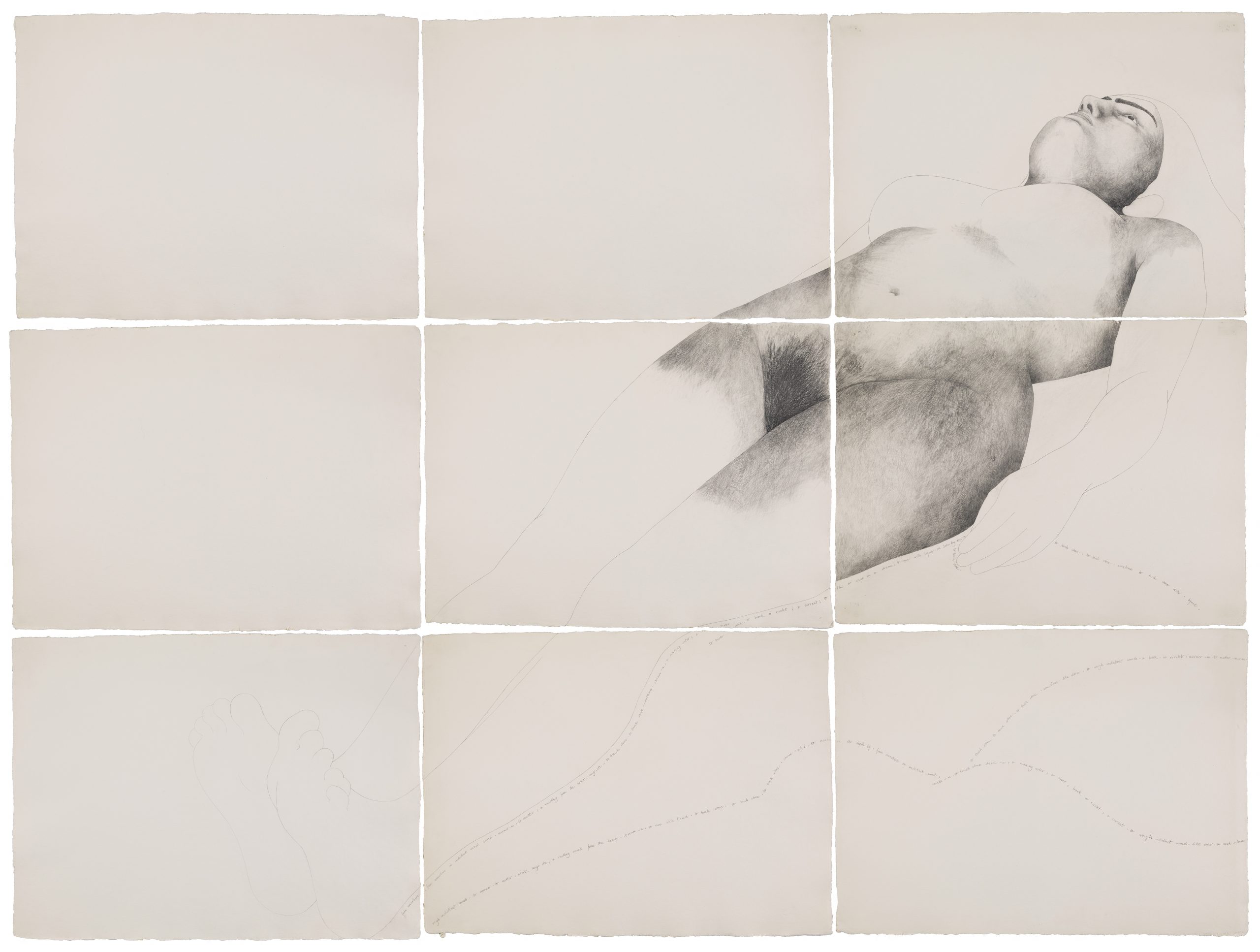

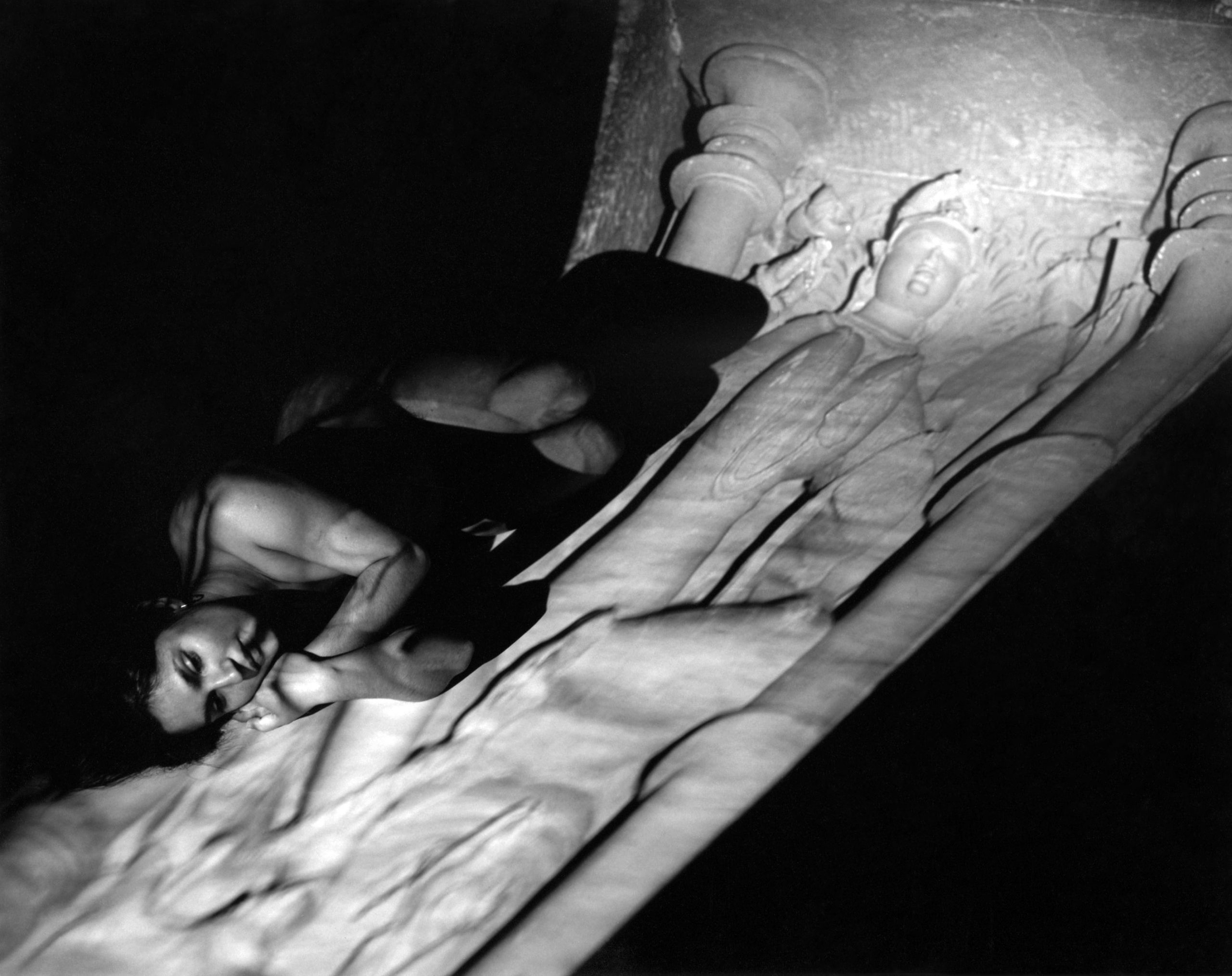

In the years after studying, she utilised her own body as a way to go against the stereotyping of South Asian women as meek and mild figures. In Synapse II, made between 1987-1992, she projects slides taken on her first trip back to India onto her naked form.

“I think trauma associates right within the body, and so this was a way of reclaiming a space I had been separated from,” she says. “Placing it onto myself physically was like an active form of recovery.” Much of her work since has probed questions of subjectivity through the conjuring of immersive, feminine spaces just like this, image-worlds in which brutalised bodies or silenced voices can exist without fear.

Biswas’ best-known work is undoubtedly Housewives With Steak Knives, a 1985 mixed-media piece in which the Hindu goddess Kali brandishes a weapon, pokes out her tongue, and wears a necklace made of dictator’s heads. “What I love about Kali is that she’s so transgressive,” Biswas smiles. “It’s still considered fearful for women to be possessive of themselves—sexually, powerfully, intellectually—but a figure like Kali gives us permission to be and do just that. She’s the goddess of war, but also peace, and I love that she’s both feminine and masculine. I find her liberating, and the density of melanin in her skin just makes her even more so.”

What is most remarkable about Housewives is how perpetually contemporary it feels. The severed head Kali holds could be Boris Johnson or Donald Trump, with its mass of white-blonde hair. It’s chillingly prophetic in that way. Perhaps that’s one of the reasons it’s reception has been so polarised? Biswas recalls the time an unknown assailant spat on the work, right between Kali’s eyes, during an exhibition at the ICA in London.

“I do think there’s something incredibly haunting about that piece,” she reflects now, “but that’s what brings all of my work together: across its various forms, there is consistently something that resonates and doesn’t let you go.”

In 2018, art historian Griselda Pollock wrote a paper introducing a handful of artists who are largely unknown in art market terms. Biswas was among them. When asked what she thinks the reason for her exclusion from the market is, Biswas says, “I have always been deeply immersed in feminist issues, colonial perspectives and the decolonisation of art. And those are three very big pills to swallow.

“I also want to possess the rights to engage with aesthetics and formal concerns,” she continues, “but changing the discourse through the aesthetics of practice… that’s male terrain, isn’t it? It really hasn’t been the case for British artists who are brown and Black, especially women. Patriarchal systems need to be challenged, but those of us who have already been challenging it for decades have been overlooked.”

“I have always been deeply immersed in feminist issues, colonial perspectives and the decolonisation of art. And those are three very big pills to swallow”

Moving subversively between forms of practice, from paintings and photographs to spectral projections, Biswas has always privileged the freedom to create over conditions that would compromise what she has to say. Nevertheless, she adds, “I think it’s really time that artists like myself found patronage, not only through commercial representation, but perhaps through museums and galleries too.”

With two major shows this year, at BALTIC in Gateshead and then at Kettle’s Yard, the art world may finally be catching up to Biswas, but still she remains a radiant and unconventional figure, multitalented and perhaps a little feared for that. She represents that most revered embodiment of female power. Just like Kali.

Joanna Cresswell is a writer and editor specialising in art, literature, history and culture

All images courtesy the artist and Kettle’s Yard

Sutapa Biswas: Lumen

At Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, from 16 October 2021 to 30 January 2022

VISIT WEBSITE