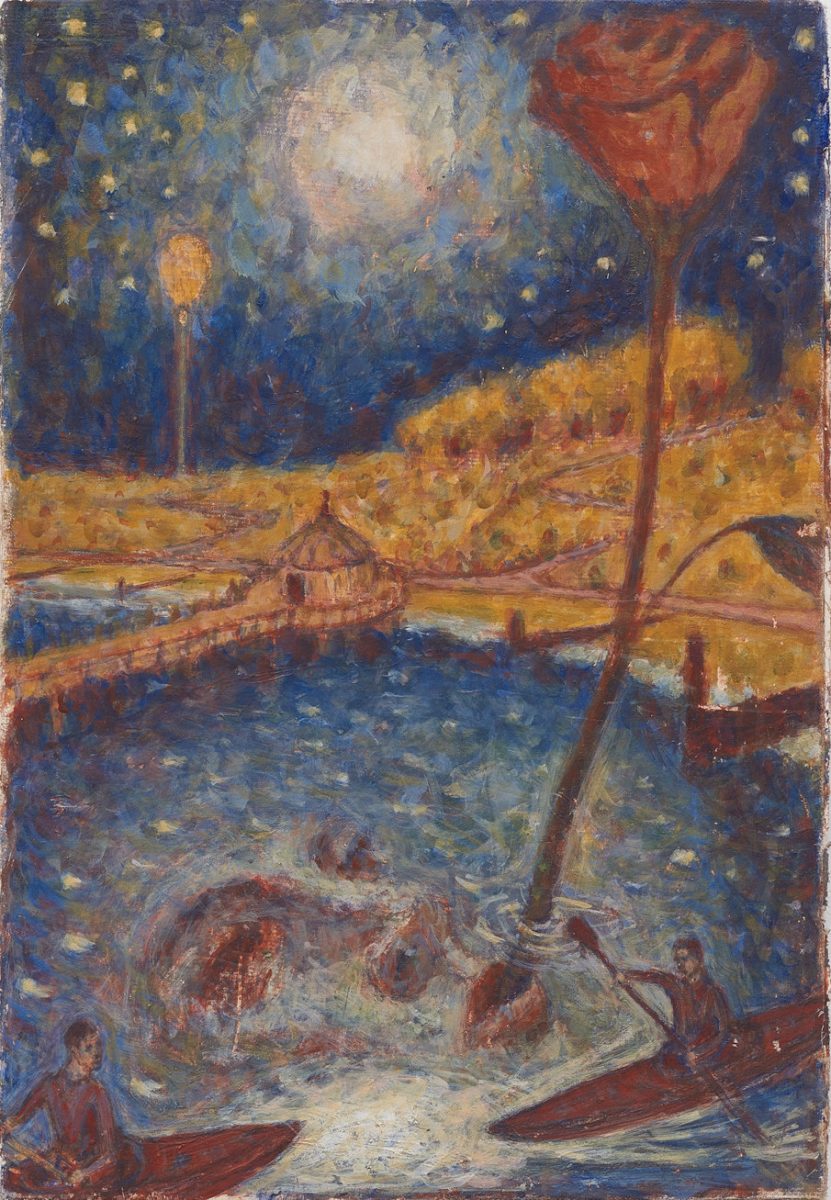

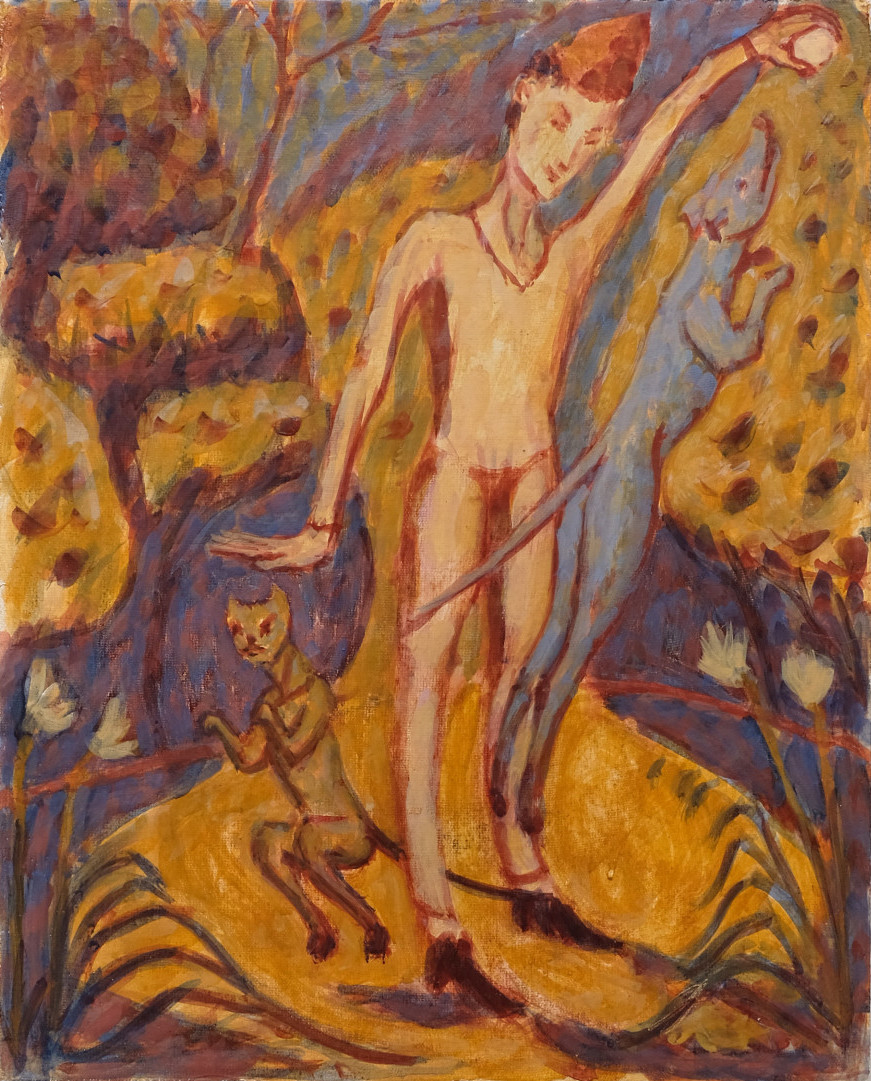

Elfin creatures tap their pointed shoes and dance under the moonlight. A face emerges from a vast lake, and hazy figures gaze down from a cloudy sky. The paintings of Glasgow-based artist Stephen Polatch surface as if from a long-buried dream, summoned from the subconscious in a whimsical moment of deeper imagination. Working with egg tempera, he paints quickly and intuitively to sketch out scenes drawn in part from walks taken in suburban British streets, made strange by their combination with mythological and religious references.

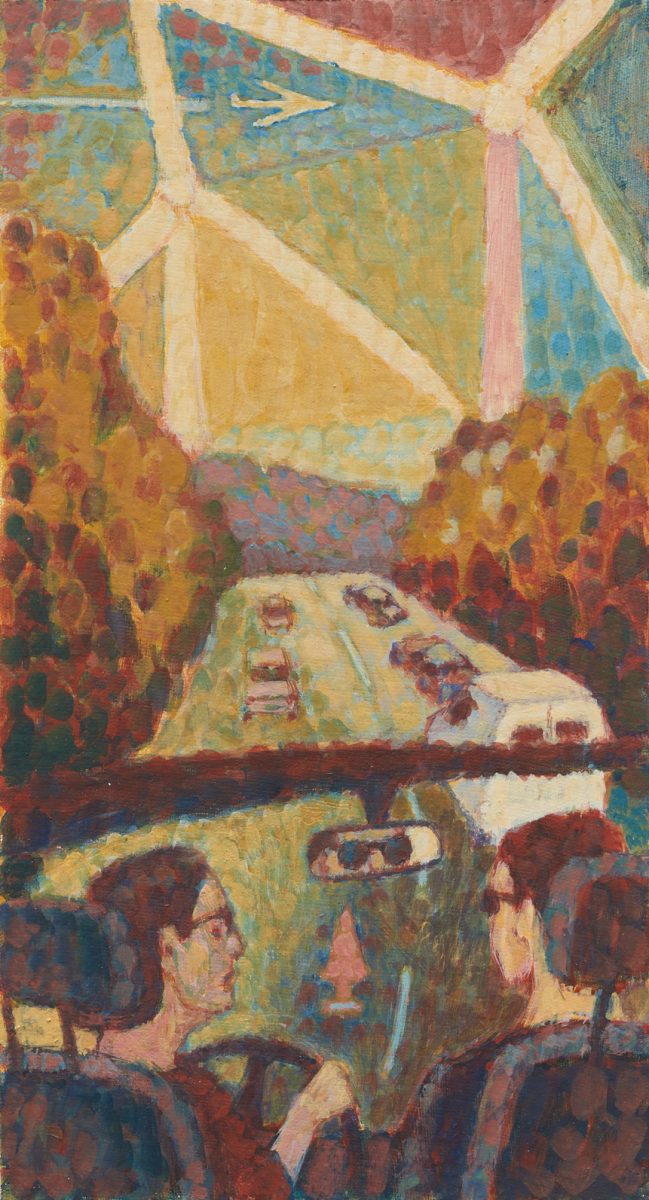

Polatch’s curious cast of characters are a meld of overlapping references, from video games to 12th-century Italian painting, as much a reflection of the artist’s own mind as they are the strange array of individual influences that we each carry with us. A tune once heard through an open car window, or a snatch of conversation in a busy park… there is a sense of fleeting encounters in these paintings, of endless motion and activity. Like the details of a dream that begin to disappear upon waking, there is also loss in these images, as if we are chasing for answers that never quite appear.

The scenes that you depict always seem to show events in the middle of unfolding, neither at their beginning or their end. How do you approach the temporal nature of these frozen narratives in your work?

I don’t usually have a clear idea myself about what happened before and after what you see in the painting. What attracts me to making still images is that there is no need to explain and describe a series of events. Instead you manipulate colours and shapes and create a mood. The narrative of the painting is ambiguous but the mood is very specific.

“What attracts me to still images is that there is no need to explain and describe a series of events”

Another way of looking at it is that the painting does have a narrative but not one that can be told. The painting starts with the first marks, develops from early stages to a problematic middle period, and finally settles in the state you see it in. This narrative can be “read” in the painting and is its real content. I don’t mean to sound like a formalist though, the imagery influences the form and vice-versa.

What was the first piece of art to have a profound impact on you?

I can remember in my grandparents’ house there was a lamp in the shape of a seaside town built up on a hill, with the houses done in low relief. I have a distinct memory of looking at that lamp and imagining walking up from the sea along the lanes, up past the houses and to the point where the lamp fixing met the ceramic lamp stand. I wouldn’t have thought of it this way at the time, but it was probably a very early experience of being transported by visual art.

A few years later I got a Playstation and after that I spent less time staring at lamp stands. In fact, I often think about the spaces in those early 3D games too, like Crash Bandicoot and Zelda, some of them were very strange and memorable. It wasn’t until I was 18 or so that I started to look at ‘proper’ art: I loved Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach and Francis Bacon. I still like those guys but happily my influences have broadened since then.

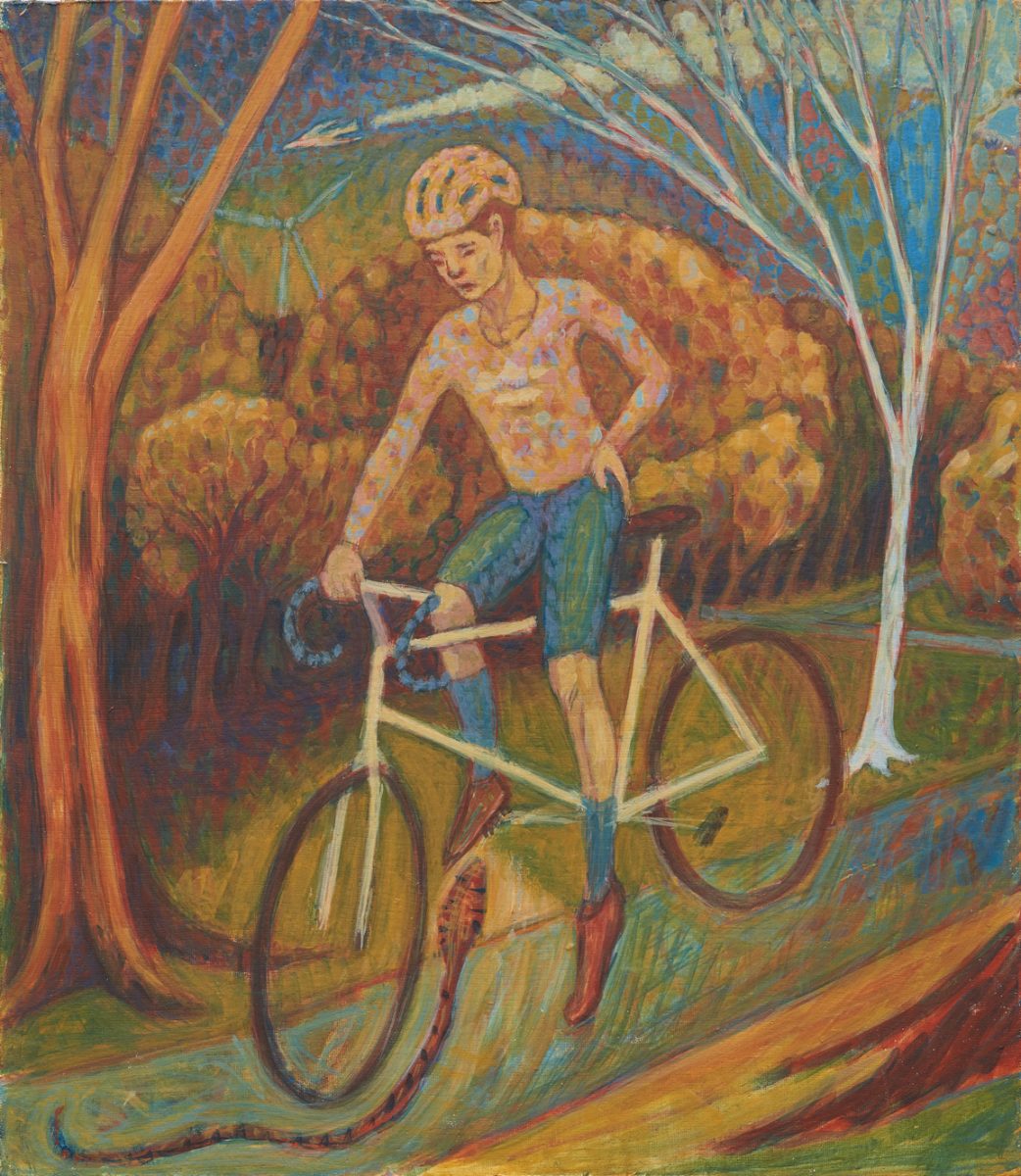

Your paintings are curiously anachronistic, in everything from your choice of egg tempera to the fashions worn by the characters in them. When and where do you imagine them being set, and what is your relationship to contemporary painting?

That’s a fair point but it’s worth saying that more recent media hasn’t surpassed egg tempera—you can get extremely pure colour and it behaves uniquely as a paint. Tempera is direct and surprisingly versatile—you can break up colour like a post-impressionist painting and use thin washes like watercolour, and you can work quickly with it. In a sense, using oil paint is more of an anachronism, all those greasy tubes and palate knives are so Victorian.

“Tempera is surprisingly versatile—you can break up colour like a post-impressionist painting and use thin washes like watercolour”

I have to agree about the fashion though, it looks like it’s from another time. I’m not sure why this is and recently I’ve been trying to dress my figures in more modern clothing. I don’t work with any kind of reference material so the characters and their dress spring from somewhere in the subconscious and apparently mine is populated by fey characters from the distant past. If I’m really honest with myself, it probably comes from looking at a lot of old paintings, especially primitive Sienese art. I try to remind myself that those artists were painting people in contemporary dress—it all looks strange and romantic to us, but to them it would have been ordinary. The images themselves, though, must always have seemed magical.

Anyway, I’ve been painting with oil this year—people wearing puffa jackets and carrying mobile phones, I’m getting up to date. My relationship with contemporary painting is that I like it and hope my work can offer something new to it. I also think that contemporary figurative painting has to learn from abstract art if it’s to move forward.

What do you think is the best gift to bring to a party?

Flowers and champagne. Not that I would ever bring those to someone else’s party—you’d be lucky to get crisps.

Animals, birds and other elements from nature make frequent appearances in your work, taking on an almost symbolic role. How important is folklore to your work, and how does a specifically British legacy of myths and magic influence you?

I prefer to use animals that I encounter frequently on walks around Glasgow, where I live, so that means a lot of cats, foxes, swans and ducks—in other words, animals commonly seen in urban and suburban Britain. I’m not saying that I’d never try painting an elephant, for example, but since I work from imagination and memory, I’d struggle to find a way to make it convincing. In this sense, living in Britain influences my paintings. The landscapes also come from what I see around me and I like to go out and draw from nature regularly.

I don’t think British Folklore has influenced me any more than French, German, Italian or anywhere else’s folklore. Some influences for recent paintings include The Magic Flute (German/Italian), Schubert Lieder (German) and Hank Williams’ songs (Alabaman), so it’s a range of stories, myths and legends.

Louise Benson is Elephant’s deputy editor