A few weeks ago, a studio flat in East London caused quite a stir when it went up for sale. Marketed as a “microflat,” but likened by many online to a “prison cell,” the property measured less than seven square metres. Articles dubbed it “London’s smallest flat”, and photos seemed to suggest that you’d have to shower while perched on the toilet.

After a fierce bidding war, it sold for 80 per cent above its minimum listing price, fetching a remarkable £90,000. The previous owner, the estate agent informed interested parties, was able to rent it out for £800 a month, should the new buyer want to make good on their “investment”.

As this story was playing out in the press, a new exhibition opened just a stone’s throw away at London’s Whitechapel Gallery, located in Tower Hamlets, one of London’ most economically deprived boroughs. It focuses on a very different kind of studio space: that of the artist.

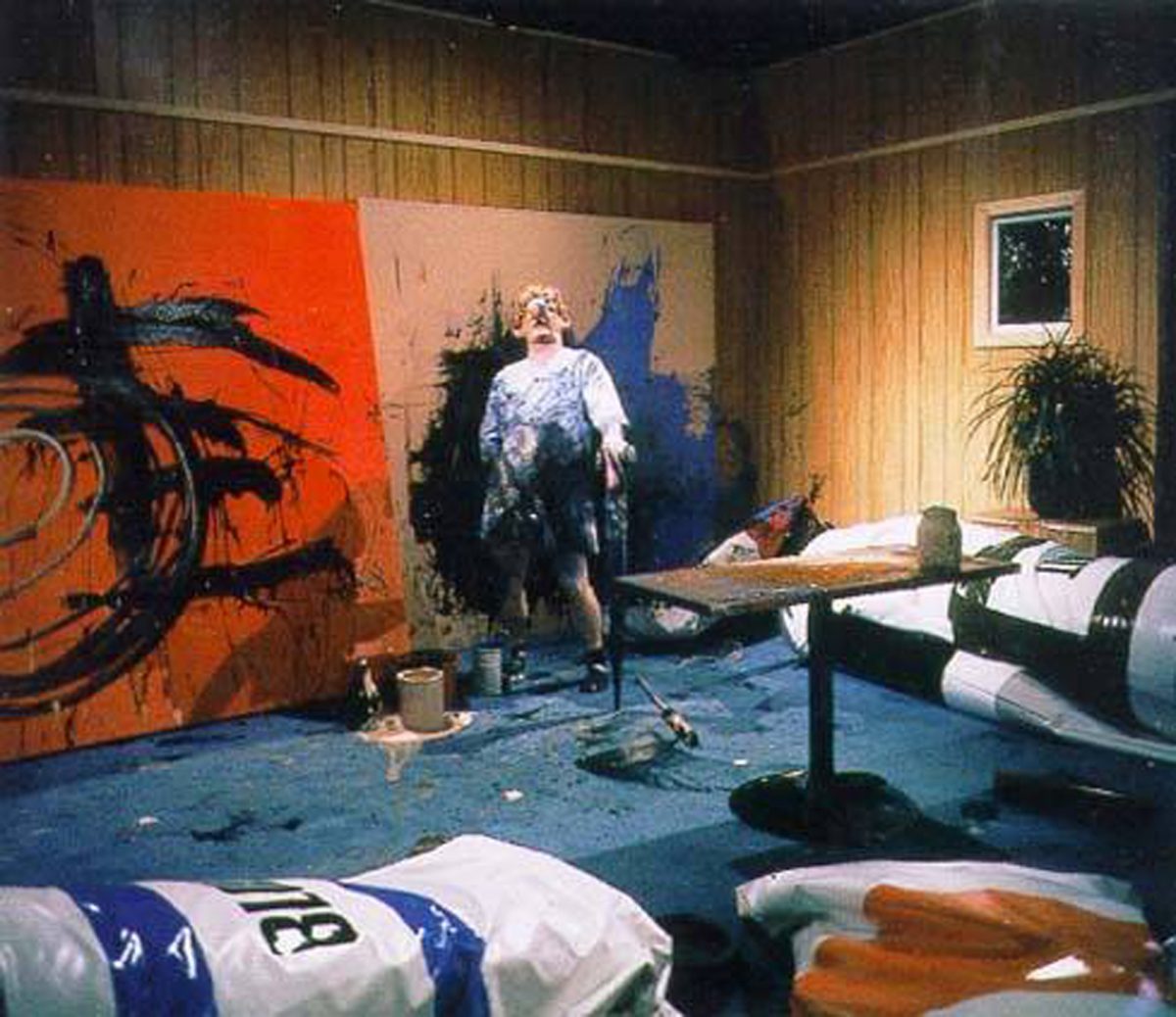

The enormous show, which spans every space within the gallery, features theme-park like reconstructions of iconic creative workspaces. Over there is a corner of Charleston, the Sussex home of Bloomsbury Group members Vanessa Bell and Duncan. Here a sliver of Kurt Schwitters’ room-sized, sculptural ‘Merzbau’. Next a wall-sized photo of Francis Bacon’s notoriously chaotic studio, with some papers scattered underneath for added effect.

“In the contemporary city of housing-crisis and property hoarding, can creative faltering be sentimentalised in this way?”

A Century of the Artist’s Studio attempts to grapple with the eternally enthralling and elusive question of how great art is made. It is a paean to process, and a nod to the desire to pull back the curtain, peep behind the canvas, and reveal just what it is The Artist gets up to all day, how their daily actions transcend labour to become The Work.

Reviews of the show have been almost unanimously breathless and glowing, but, despite the cornucopia of artists’ work on display, I have to say it left me cold. Emerging from the gallery, instead of dwelling on how the studio can be a site of refuge or resistance, all I found myself thinking was how much a seven square metre studio space in East London might cost per month. how much that might be on top of a month’s rent; how much you’d have to make in order for it to be worthwhile. Microflats and co-working spaces and extortionately priced Hackney Wick warehouses swam before my eyes.

The curator of the Whitechapel show, the longstanding director of the gallery Iwona Blazwick, suggests that the artist’s studio represents not just “an archive of thinking, being and making, but also of indecision, boredom and failure.”

Yet, in the contemporary city of housing-crisis and property hoarding, can creative faltering be sentimentalised in this way, as an intrinsic part of the artist’s everyday, their struggle towards creative fulfilment? Can failure be an option? Surely, with space at such a premium, the artist’s studio can only be a marker of success? Not a crucible of experiment and play, but evidence of financial stability or commercial viability?

In mid-March, the cheapest studio available from SPACE, London’s largest studio provider, costs £391 per month to sub-let, a figure that “will increase to £404 per month from 1st April,” according to the rental advert. The story is similar across the board.

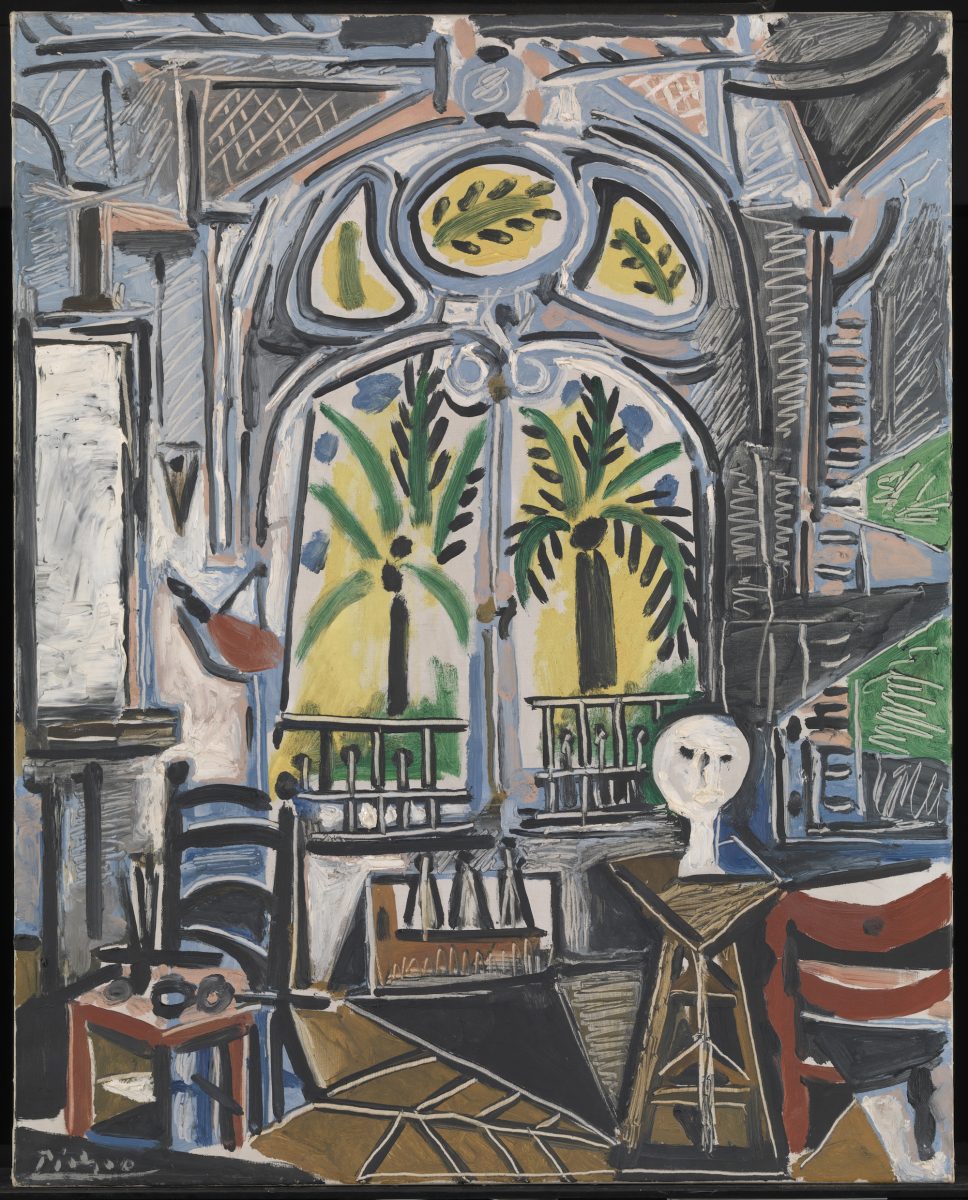

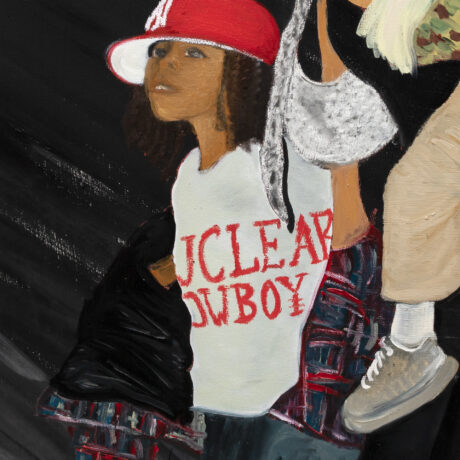

- Left: Pablo Picasso, L'Atelier (The Studio), 1955. © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2021; right: Inji Efflatoun, Portrait of Inji Efflatoun, 1958. Courtesy Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art

ACME studios, which was founded “by artists, for artists” in 1972, and proclaims to provide “studio space for fine artists who are unable to afford to rent workspace on the open market,” came under fire in April 2020 for pushing ahead with a 7% rent increase, just as the pandemic began to make a severe economic impact on artists (though it did offer three-month payment breaks to tenants).

“Like microflats, it seems artist studios are often most rewarding, not for tenants, but for absent investors”

Unlike most other studio providers in the capital, ACME offers long-term live/work residencies, guaranteed to artists for five years, stating that this scheme “allows artists more time to concentrate on the development of their work and careers, and less time working to survive.” But, even before the 2020 hike, residents were paying £565 a month. Rent for the current group is £720, a whopping 27.4% increase, which puts the charity’s spaces on par with an average London room rental.

In the grand scheme of housing, cladding, and cost of living crises, the accessibility of surplus space (space not just to survive but to thrive) might not seem like the most pressing concern. But these issues are intrinsically linked. The question of who is able to comfortably develop their practice, create work, and be part of an artistic community is a crucial part of any broader question about who contemporary cities are being shaped for, and what kind of society we want to live in.

In London, and in other urban centres that used to be attractive to artists at all stages of their lives and careers, the answer increasingly seems to be that ‘young creatives’ are being priced out, or pushed into ever-smaller and more dismal conditions. Any notion of creating ‘affordable working spaces’ for artists is often an illusion.

“The artists arrive: the property appreciates in value. Then the artists are pushed out, and the reason why people came is no longer there”

Indeed, in an incendiary open letter addressed to “Slumlords of the Art World,” the Acme Firestation Residents 2020-25 accused the organisation of having “misrepresented” the residency. Detailing relentless noise disturbances, lack of hot water, and maintenance problems, it declared the live/work spaces “unfit” for purpose. Like microflats, it seems artist studios are often most rewarding, not for tenants, but for absent investors.

It’s perhaps surprising then, with this economic trash-fire raging apparently unchecked, that the artist’s studio is being romanticised and idealised more than ever. Celebrated artist’s studios are preserved and sold to galleries for vast sums, gallery exhibitions are eulogising creative spaces, and magazine spreads are poring over acclaimed artists’ living and working arrangements.

This is the logic of gentrification. In cities such as London, New York and, more recently, Berlin, a familiar pattern is followed. “The artists arrive: the property appreciates in value,” Elke Kupfer, an artist who was forced out of her studio in the Kreuzberg district of Berlin in 2015, explained to the Art Newspaper in 2018. “Then the artists are pushed out, and the reason why the people came in the first place is no longer there.”

Changing this narrative and turning the tide back against studios only being available as luxury workspaces for the financially secure will involve a concerted effort. It will need to take into account the precarious conditions rife within the creative industries, and recognise how this connects with other social issues: rising homelessness, booming property prices, and the displacement of communities.

Maybe it’s harder to romanticise advocating for rent controls, eviction bans, and a dramatic shift in the balance of power between property tycoons and tenants than it is to eulogise the exalted, archetypal artist’s studio, but perhaps that’s not a bad thing. Perhaps what we desperately need is less reminiscing about the past and more action in the here and now.

Eloise Hendy is a writer and poet living in London