The term “female strength” is a loaded one. For the most part, it is an idea synonymous with resilience and even suffering. While masculinity is inextricably tied to physical power, women are more likely to be connected through the notion of physical endurance—just ask anyone who has given birth. Physical fortitude is an accepted facet of male gender roles, but it is still surprisingly hard to find equivalent female counterparts. Even as gym-going has become a fashionable pastime and various fitness trends take hold, there is still an overwhelming aesthetic that prefers women to look alluring, even when they are testing their physical limits. The huge scrutiny that so many female athletes undergo, the prime example being Serena Williams, shows just how narrow the perceptions of womanhood remain in some people’s eyes.

I pondered this recently while attending an EVE Pro Wrestling event. The self-appointed Riot Grrrls of wrestling sport use the tagline “Punk, Feminist, Empowered”, and hold an absolute zero tolerance policy on any kind of harassment or shaming. As I stood next to the ring, in a sweaty venue housed under the arches in Bethnal Green, I watched women engage in various theatrics while they pounded each other to a pulp.

Events like this have grown in popularity thanks to the huge success of Netflix’s GLOW, a fictional take on a real 1980s wrestling show, which manages to toe a thin line between subverting the male gaze and revelling in it. But one of the amazing takeaways from the production came from actor Betty Gilpin, whose Glamour op-ed explained how her wrestling training not only changed her relationship with her body for the better but built a collaborative bond with her co-stars which was based on not only emotional, but physical trust.

“While masculinity is inextricably tied to physical power, women are more likely to be connected through the notion of physical endurance”

That same faith is demonstrated at EVE, where women of all shapes and sizes engage in a delicate balance of choreography and improvisation to tackle their opponents. I saw one wrestler jump from the rafters and smash her rival into a table, while another flung herself from the ropes and use her thighs to trap her counterpart in a headlock. As the sweat (and blood) sprayed, I was delighted by the action, and shocked by how seldom I have witnessed women who do not fit a carefully crafted aesthetic ideal showing off feats of physical strength.

This is largely informed by visual culture. What few references we have often lie within very specific parameters. Take, for example, the impossible standards of Teyana Taylor, who starred in the video for Kanye West’s track Fade. Here, she engages in some sort of enigmatic, hyper-sexualized workout routine while sporting the world’s tiniest thong. It is something of a microcosm for the swathe of media declaring #strongnotskinny, while promoting narrow and possibly dangerous expectations for female physical health. And let’s not forget the legacy of the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue, which first utilized the lithe female form as a way to boost sales figures among its predominantly male subscriber base.

When it comes to contemporary art, representation remains equally limited. One of the few examples comes from Robert Mapplethorpe (currently the subject of a year-long, two-part exhibition at the Guggenheim), whose tender images of bodybuilder Lisa Lyon were inspired by the photographer’s quest for a “sculptural ideal”. Though he takes classical aesthetics as a starting point, his images challenged accepted beauty standards of the time and toy with binary readings of gender and female physicality.

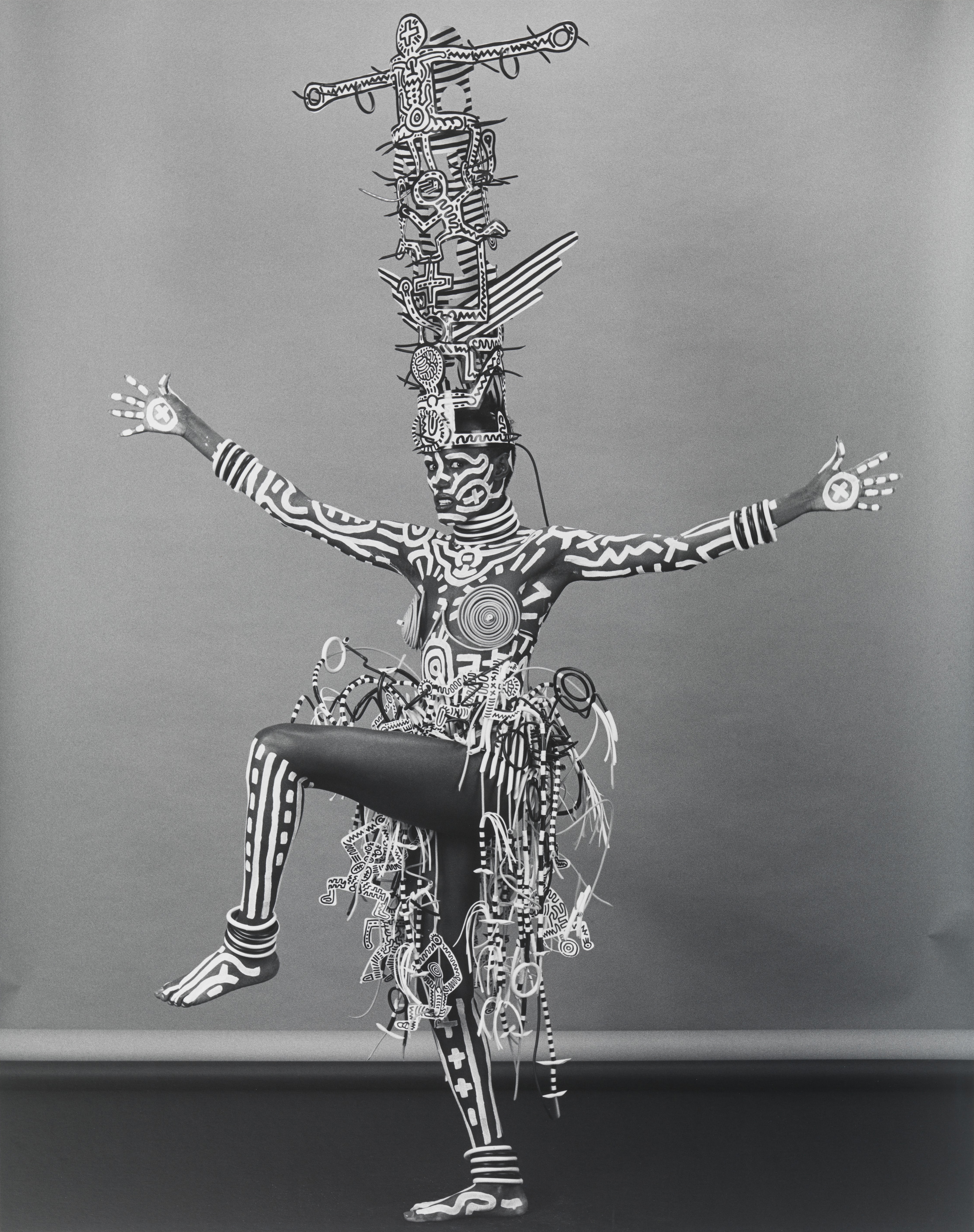

In a similar vein, Jean-Paul Goude’s collaborative relationship with Grace Jones (who was also a subject for Mapplethorpe) helped catapult the singer to stardom, thanks to her androgynous, formidable persona. However, to say that elements of Goude’s oeuvre are problematic would be an understatement. Just take his 1981 book Jungle Fever, in which the female black body is exoticized to the extreme, and images of stripper and bodybuilder Kellie Everts present a fetishistic notion of female physicality, which is often played for laughs.

“His images challenged accepted beauty standards of the time and toy with binary readings of gender and female physicality”

More recently, Camille Vivier manages to capture the female body with greater nuance. Her photographs of muse Sophie present a more realistic example of a professional bodybuilder, where her journey to become “indestructible” has kept her off the path of steroids and surgery that so many competitors succumb to. In a recent interview the pair discussed how important it is that Sophie is presented as an individual, not as a vessel for a particular idea of beauty. The model explains: “Women are complex and muscles are not the monopoly of men.”

Though Vivier’s work does break from many accepted tropes, the fact remains that more diverse portrayals are still scant, and portrayals of strength are usually limited to depictions of the body, as opposed to action. In a recent Salty article by Caroline Anderson, she explains the appeal of “being able to benchpress [her] husband” while remaining plus-sized, and it is a rare example of a media story that centres around newfound physical strength—one that doesn’t focus on any kind of traditional aesthetic value. She is not talking about toning up or losing weight, but about the pure joy and freedom found in pumping iron. There are other women who are sharing their stories via social media, but they tend to be few and far between.

“She is not talking about toning down or losing weight, but about the pure joy and freedom found in pumping iron”

It is also important to remember that, while “working out” is a key component to physical strength, it is by no means the ultimate. In my quest to find other representations of women, I recalled a particularly striking painting by Russian avant-garde artist Aleksandr Deineka, which was on show at the Royal Academy as part of Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932, back in 2016. Construction of New Workshops features a female labourer straining under the weight of a container that needs transporting, while a slighter textile worker looks on.

The labourer’s muscular heft is defined against the lines of her dress, her calves and bare feet flexing with the effort of it all. In this moment, these two women are not fulfilling any aesthetic desire, they are fulfilling the ideals of the Soviet Union through brute force. In this image, Deineka captures a completely different view on physicality, which transcends the male gaze and delights in some sort of collective joy (just revel in the textile worker’s grin). It is a remarkable portrayal of female strength, and one that remains shockingly rare. It seems that if we want to change the imagery of the future, we might have to start looking back.