Josh Kline, Thank You for Your Years of Service (Joann / Lawyer), 2016. 3D-printed plaster, ink-jet ink, and cyanoacrylate; foam; polyethylene bag, 60.96 x 81.28 x 109.22 cm. © Josh Kline, courtesy the artist, Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London & 47 Canal, New York, NY

It’s 2031, society has become highly automated and once stable middle-class professions such as lawyer, accountant, banker, secretary have become obsolete, following the jobs of taxi driver, trucker, factory worker down the pan. “What is to be done with the hundreds of millions of people who will never earn another paycheck?… Will you Airbnb your body out to strangers in order to make the rent?”

This stark scenario was served up at the Serpentine Galleries’ annual ideas festival this past weekend by the artist Josh Kline (whose dystopian 2016 installation Unemployment presents 3D-scanned sculptures of real jobless professionals bagged up like trash). The theme this year was Work, and how to prepare for a future where big data and automation have eliminated most jobs. The ten-hour event at the Royal Geographical Society brought together some fifty philosophers, artists, musicians, writers, poets and filmmakers to grapple with what labour and leisure will mean in a post-work future.

A panel discussion with Walthamstow Labour MP Stella Creasey debated Universal Basic Income and how to adapt to the tech economy; Rana Dasgupta considered possible scenarios if mass joblessness destroys capitalism—among them war, authoritarian regimes, alternative economies and “reservations” for spiritual activities outside the political system (think modern-day monasteries).

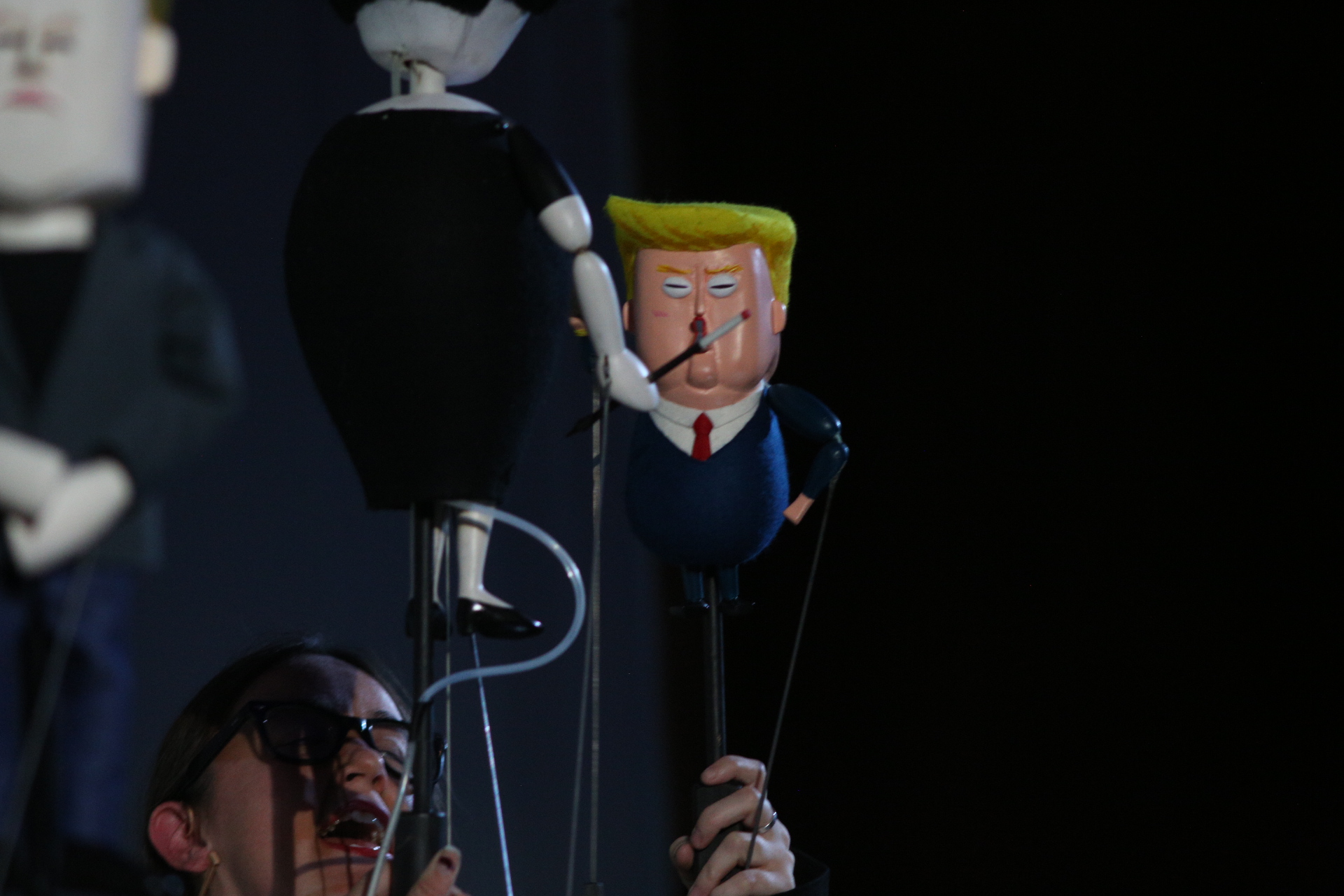

Amid all the heavy stuff, there was irreverent fun to be had too. In homage to John and Yoko’s famous 1969 Bed-In for Peace in New York, Beatriz Colomina organized her own bed-in in Frida Escobedo’s pavilion and Pedro Reyes staged part of his puppet sci-fi comedy Manufacturing Mischief, featuring a rapping Karl Marx, a tiny yappy Trump and Elon Musk as an exploding robot.

Every year it offers a fantastic slice of very current art world discussions—and a taste of what’s to come in critical thinking and our wider world. So what were the key conversation points?

Plug In or Rewild?

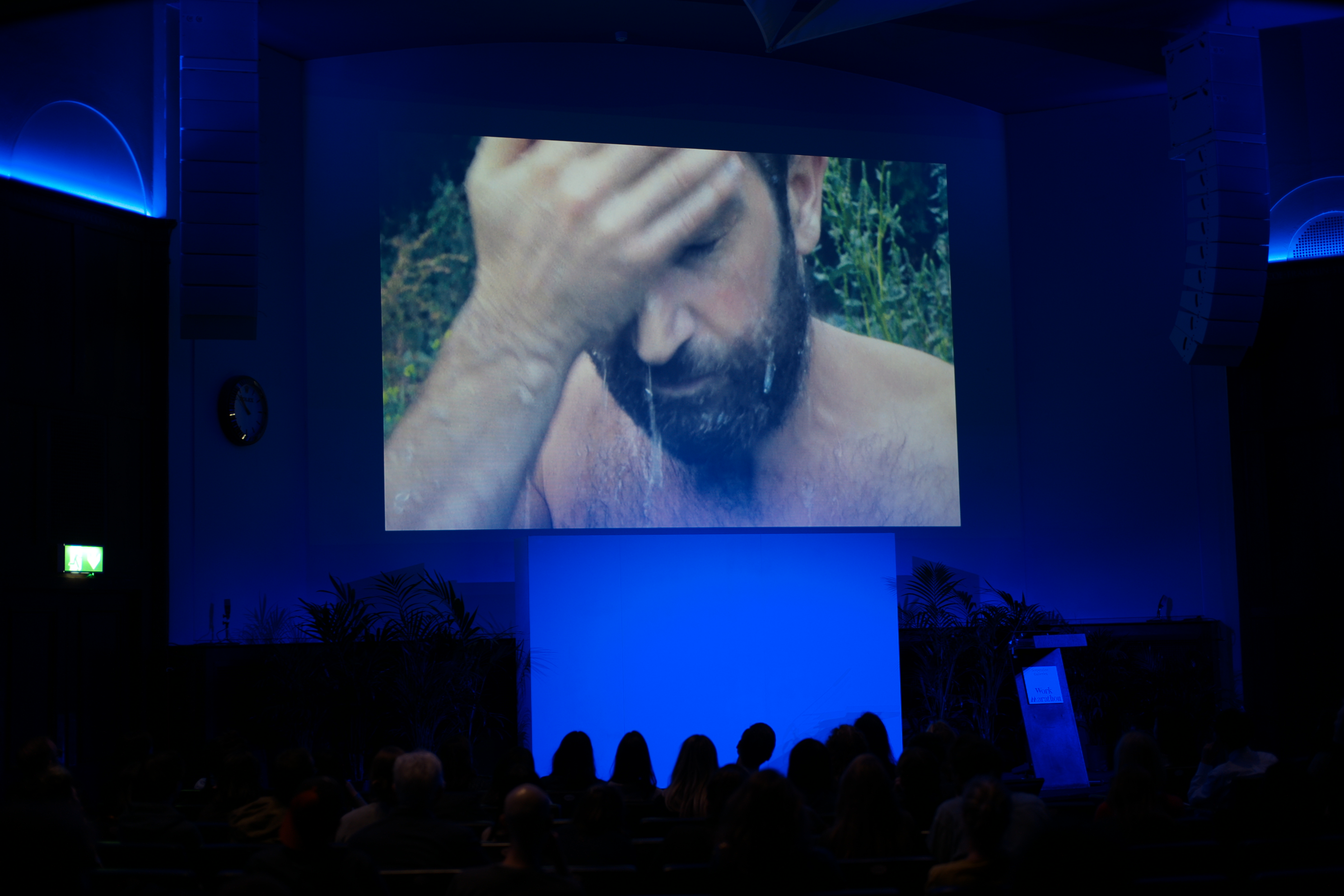

The marathon opened with the often tempting idea of ditching our tech-dependent lives and going back to nature. Lily Cole’s new short film Marblehill follows Mark Boyle, author of The Moneyless Man, who gave up all technology three years ago for ecological reasons and now lives on his wits in the wilds of western Ireland. Boyle built his own cabin and cycles twenty miles to the nearest lake to fish, going hungry if he hasn’t caught food, but this “work” makes him happier than he’s ever been. “There’s a joy and an aliveness that comes from the connection to the earth,” Boyle said in an uplifting (if idealistic) conversation with anthropologist James Suzman. On the subject of sustainability, Boyle asked, “Why would we want to sustain a culture that is wiping out life on earth?” Social or ecological breakdown, he reckons, will ultimately force us to change.

The Final Warning

“In the Anthropocene, we are heading at a greatly accelerated rate towards a dead end, thanks to the consumerist model,” warned Bernard Stiegler, whose ideas about work formed the backbone of this year’s Serpentine Marathon. He and his colleagues are urgently trying to steer humanity from our current toxic age of war, famine, corruption and environmental degradation (the Entropocene) towards a new epoch (the Neganthropocene), where work is rethought as a mobilization of collective knowledge. As jobs are taken over by robots—around fifty percent in the US and France in the next twenty years, according to some studies—he argues that wealth inequality and rapacious consumption must be reversed and a new economic model adopted. “We have twenty years to make the change before the situation is catastrophic,” Stiegler said.

The Working Bed

In 2012, architecture historian Beatriz Colomina came across the staggering statistic that eighty percent of young professionals in New York regularly work from their beds. The internet and social media have broken down the divide erected by industrialization between factory and home, work and rest. Playboy founder Hugh Hefner presaged this shift, turning his bedroom into the epicentre of his porn empire and rarely venturing outside. His rotating, vibrating bed was kitted out with a fridge, hi-fi, filing cabinet, TV, video camera, work table; it was where he conducted interviews and cavorted with bunnies, seamlessly fusing business and pleasure. But perhaps AI will offer the solution, forcing an end to current demands for hyper-productivity.

Josh Kline, still from Universal Early Retirement (Spots #1 & #2), 2016 © Josh Kline, courtesy the artist, Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London & 47 Canal, New York, NY

The Happy Cage of the Me Society

“Most people’s jobs are pointless, they only do them so they can earn money to do their real job, which is to go shopping”—filmmaker Adam Curtis’s trenchant take on the life-work cycle today. What we think of as work isn’t really work in the socialist sense that industry was supposed to create a better, fairer world. “Self-expression and individualism is the mood of the age,” argued Curtis. “The downside is that you’re not very powerful by yourself, and when things go wrong you’re alone. We’ve lost a real sense of collectivism.” Part of the problem is that we’re too comfortable, so we end up being managed by politicians and computers. As Curtis said, “We’re in a happy cage… You know that you’re in the system but you like the system.”

Want to learn more about art and labour? You can read about fully automated luxury communism in Hettie Judah’s issue 36 essay

BUY ISSUE 36