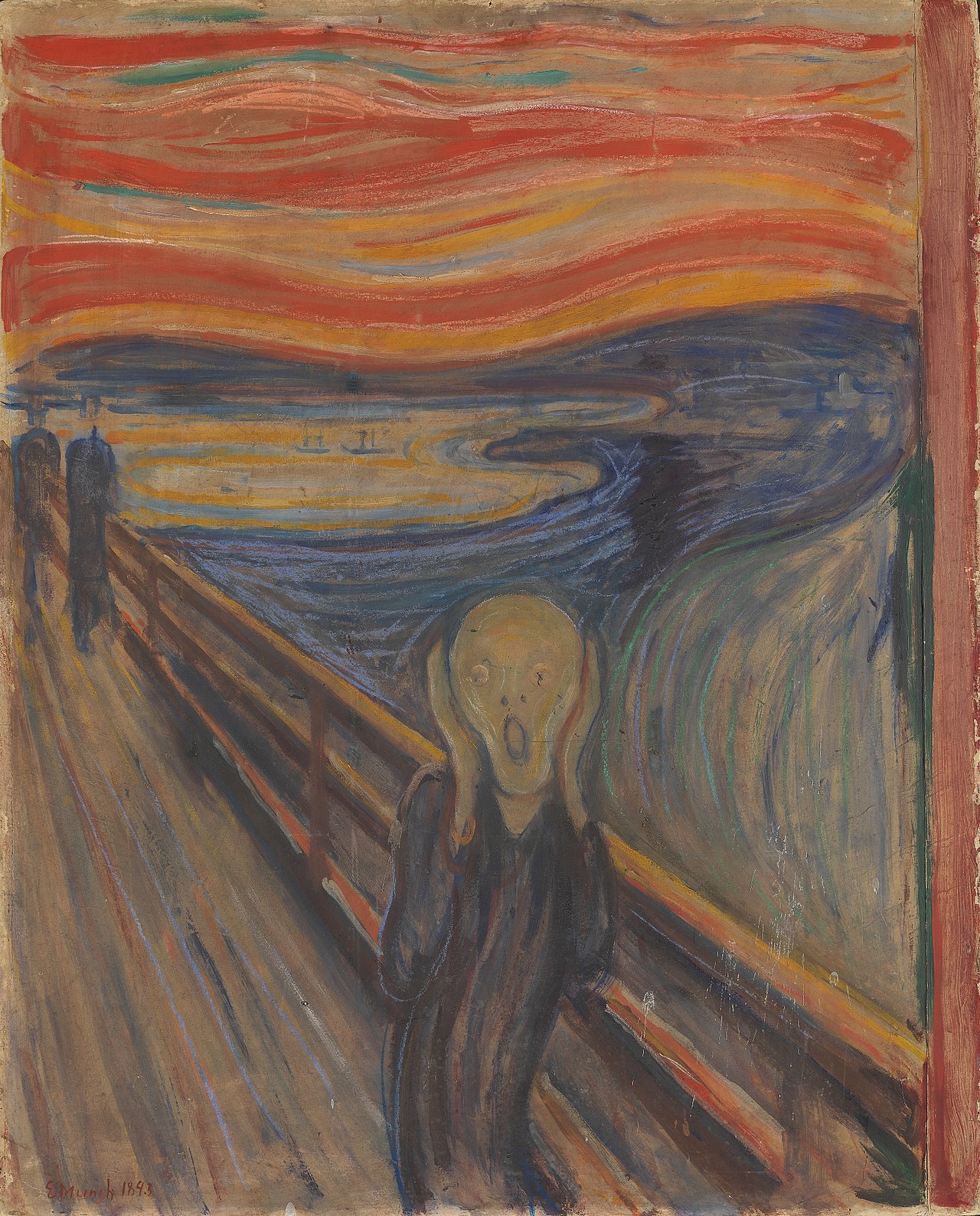

One of the most renowned representations of psychological anguish in the history of art has to be Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893). Akin to Francis Bacon’s “screaming popes”, Munch’s tortured figure embodies existential agony and the dark extremes of emotional turmoil. However, unlike Bacon, Munch’s painting has been reproduced on countless occasions, commodified into countless products. A cursory internet search brings up the proverbial—socks, tote bags, hoodies, mugs—as well as the more obscure: a $600 dress, a packet of plasters and a re-imagining of the painting starring a cow (appropriately, by Edvard Moo-nch). Woven into popular culture, too, Munch’s figure also appears briefly in an episode of The Simpsons, and is said to have inspired the “Ghostface” mask analogous with the Scream slasher films. And that’s without even unpacking the obvious relationship with the emoji “gasp” face.

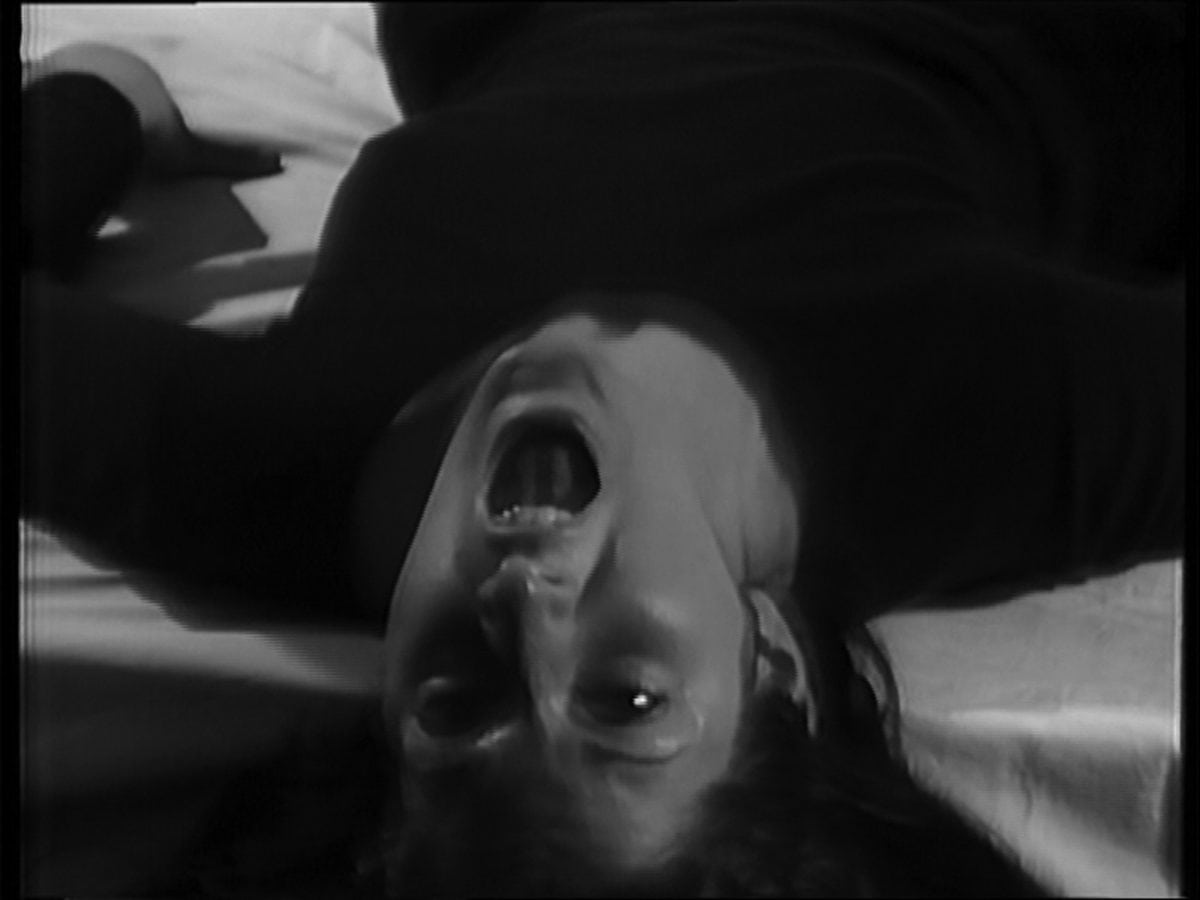

- Marina Abramović, Freeing the voice, 1975. Single screen projection © Marina Abramović. Courtesy Lisson Gallery

The open intensity of Munch’s expressionist practice, particularly the way he foregrounded his own human vulnerability, made a deep impression on Tracey Emin as a young artist. The Scream is cited as one of her favourite works. In 1998, Emin made a short video work titled Homage to Edvard Munch and All My Dead Children, in which she appears naked, crouched in the foetal position, at the edge of the water of the Oslo Fjord. As the camera pans across the water, we hear her scream, suspended unbearably for a whole minute. In October 2013, in collaboration with Oslo’s Ekeberg Park—looking over the same landscape in which Munch’s painting is set—Marina Abramović staged a collective screaming performance with over 300 citizens.

“When you are pushing against your own limits, the voice turns into a sound object”

No stranger to the visceral, existential power of the scream, in 1975—at the Student Cultural Center in Belgrade—Abramović first performed Freeing the Voice. The direction was simple; “I lie on the floor with my head tilted backwards. I scream, until I lose my voice.” In the video documentation of the performance, the camera has been angled so that Abramović’s face fills the screen. The psychic and physical endurance of the body is centred. Her mouth is wide, projecting an uninterrupted, wordless scream, which builds into a hysterical crescendo, faltering, and then gradually falling into slow, deep breathing. “When you are screaming in this way, without interruption, at first you recognize your own voice,” she explained, “but later, when you are pushing against your own limits, the voice turns into a sound object.”

Abramović’s understanding of the scream as a form of catharsis—a way to release tension from the body and mind—can be perhaps aligned with Dr Arthur Janov’s controversial Primal Scream Therapy, developed as a means to elicit repressed emotional pain from his patients and treat anxiety, trauma and stress disorders. Primal Therapy became a popular, cultural phenomenon in the 1970s, and despite some sustained presence in America, is now generally regarded as pseudoscience. However, the image of the scream as a way to radically rupture the conventional norms of behaviour in public space is an interesting one to hold onto. In the 1980s, radical performance artists like Rachel Rosenthal and Karen Finley used the scream—in tandem with shouts, sobs and laughs—in order to communicate a non-verbal, transgressive physicality.

Yoko Ono, along with John Lennon, reportedly went through months of intensive therapy with Janov, although their engagement with the psychic power of the scream far pre-dates that. In an interview with Rolling Stone in 1971, Lennon says, “Listen to ‘Twist and Shout’. I couldn’t sing the damn thing I was just screaming. Don’t get the therapy confused with the music. Yoko’s whole thing was that scream.” In her legendary work Voice Piece for Soprano (1961), Ono invited the audience to engage in a moment of rebellion against traditional museum etiquette. The work consists of a microphone, loudspeakers and the instructions: “Scream against the wind/against the wall/against the sky.” The work was reportedly so popular with audiences during her 2010 retrospective at MoMA in New York, that the museum was forced by its staff to turn the volume down. I scream, you scream, we all scream…

Summertime Angst – Art in the Age of Uncertainty

BUY ISSUE 35