My first experiences with hallucinogens were in my early twenties. The first time, I made a lot of mistakes: I took it on my own, in a confined space. It wasn’t an entirely good experience but neither was it all bad—it was transformative.

For someone who had suffered various bouts of depressive thoughts, the therapeutic benefits of LSD were a revelation to me. In my experiences, the chemicals seemed to break all the chains of regular destructive thoughts in my brain and made reality appear less stable and fixed. I was able to confront the darkest and most repressed fears in my own mind, to explore them. Back IRL, I felt stronger—and relieved.

LSD was initially used as a treatment for depression, anxiety and alcoholism. But by the 1960s, even its earliest advocate, Albert Hofmann, deemed that acid was being misused recreationally, and the political establishment at the time banned LSD from medical research for more than thirty-five years. It was only in 2007 that Swiss medical authorities permitted LSD to be used in clinical trials again.

“I was able to confront the darkest and most repressed fears in my own mind, to explore them”

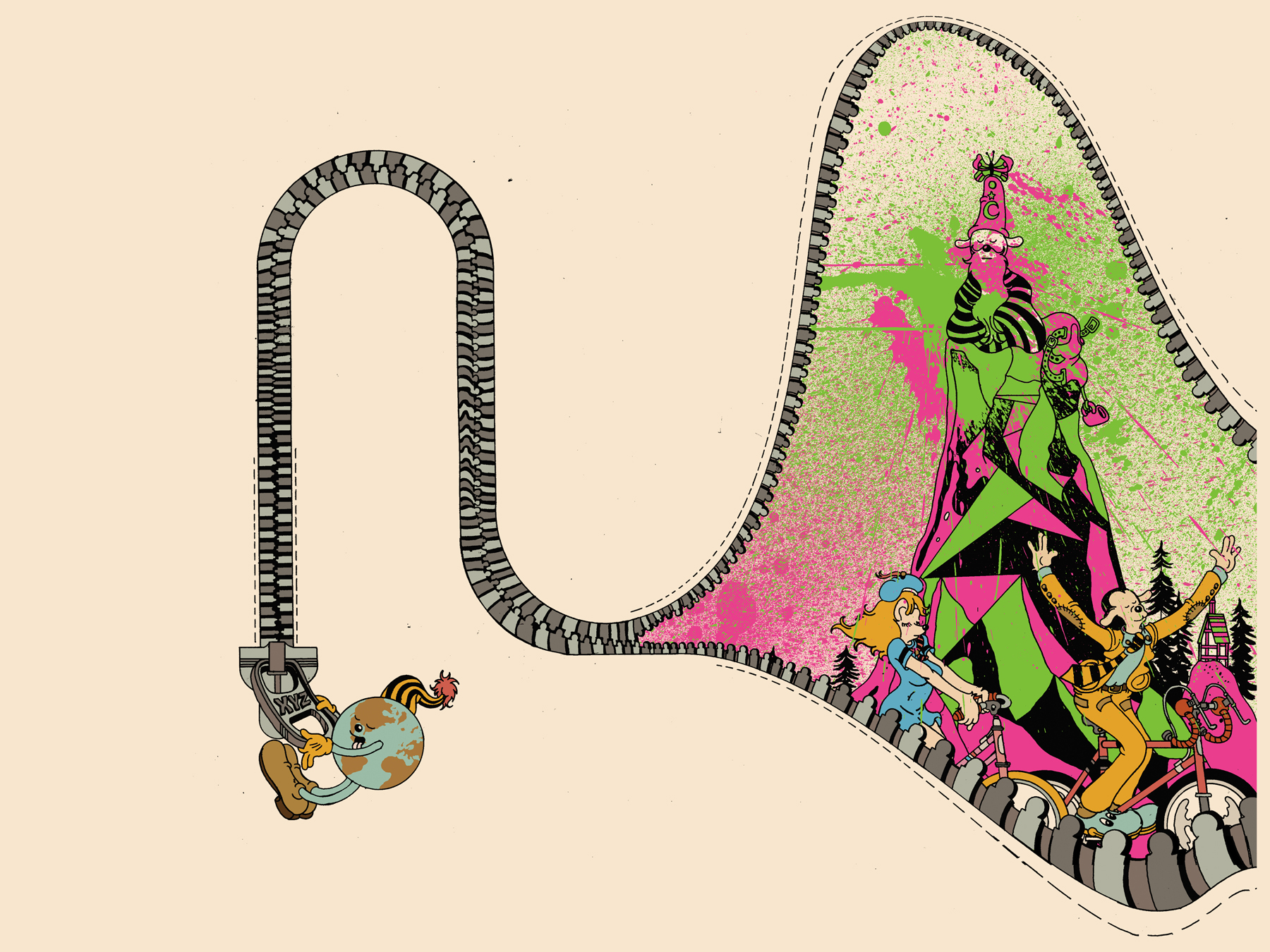

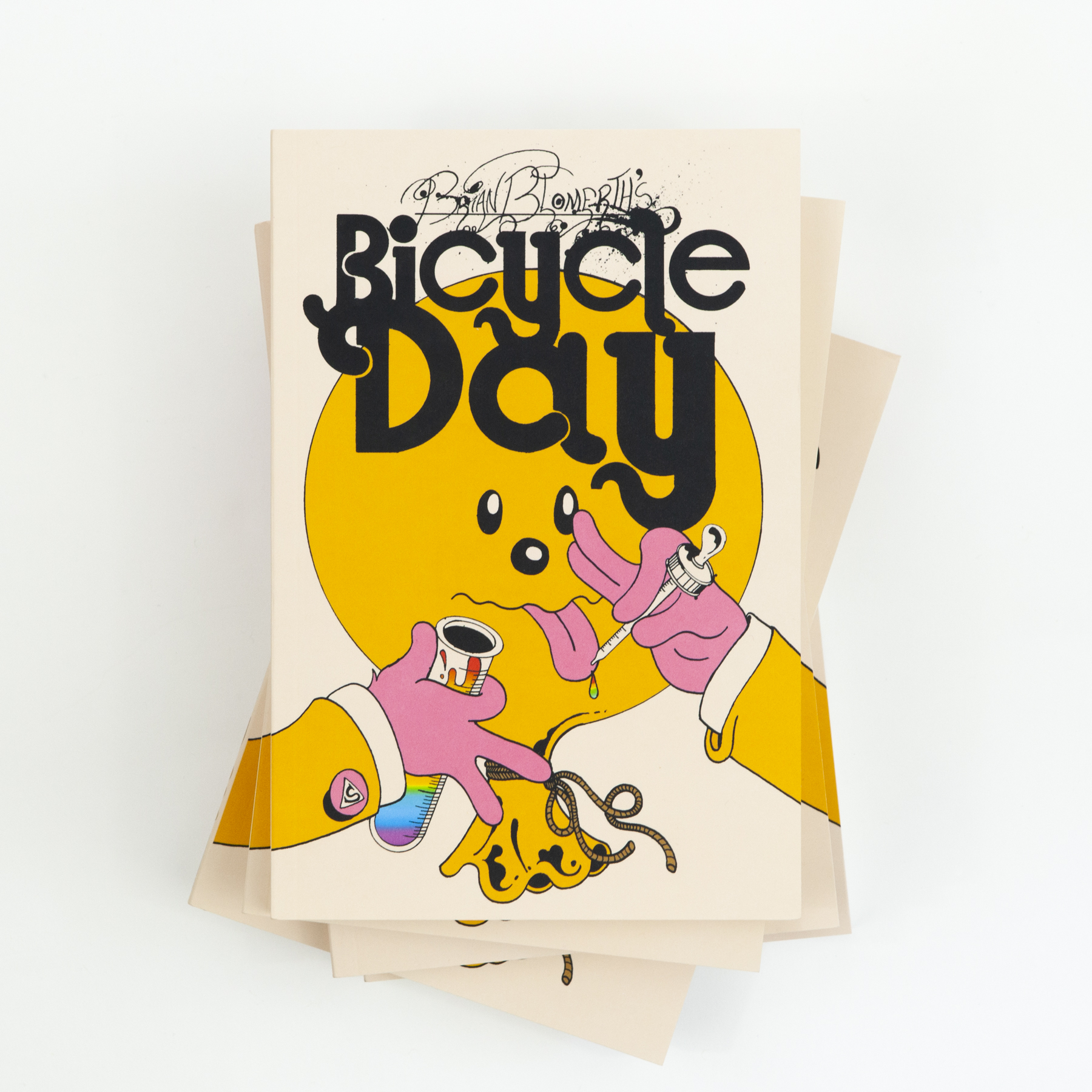

Individual experiences with LSD are what inform artist Brian Blomerth’s Bicycle Day, a graphic novel narrating the historic moment Albert Hofmann—at the time, a young chemist working at Sandoz Pharmaceuticals in Basel—first synthesized and used LSD-25.

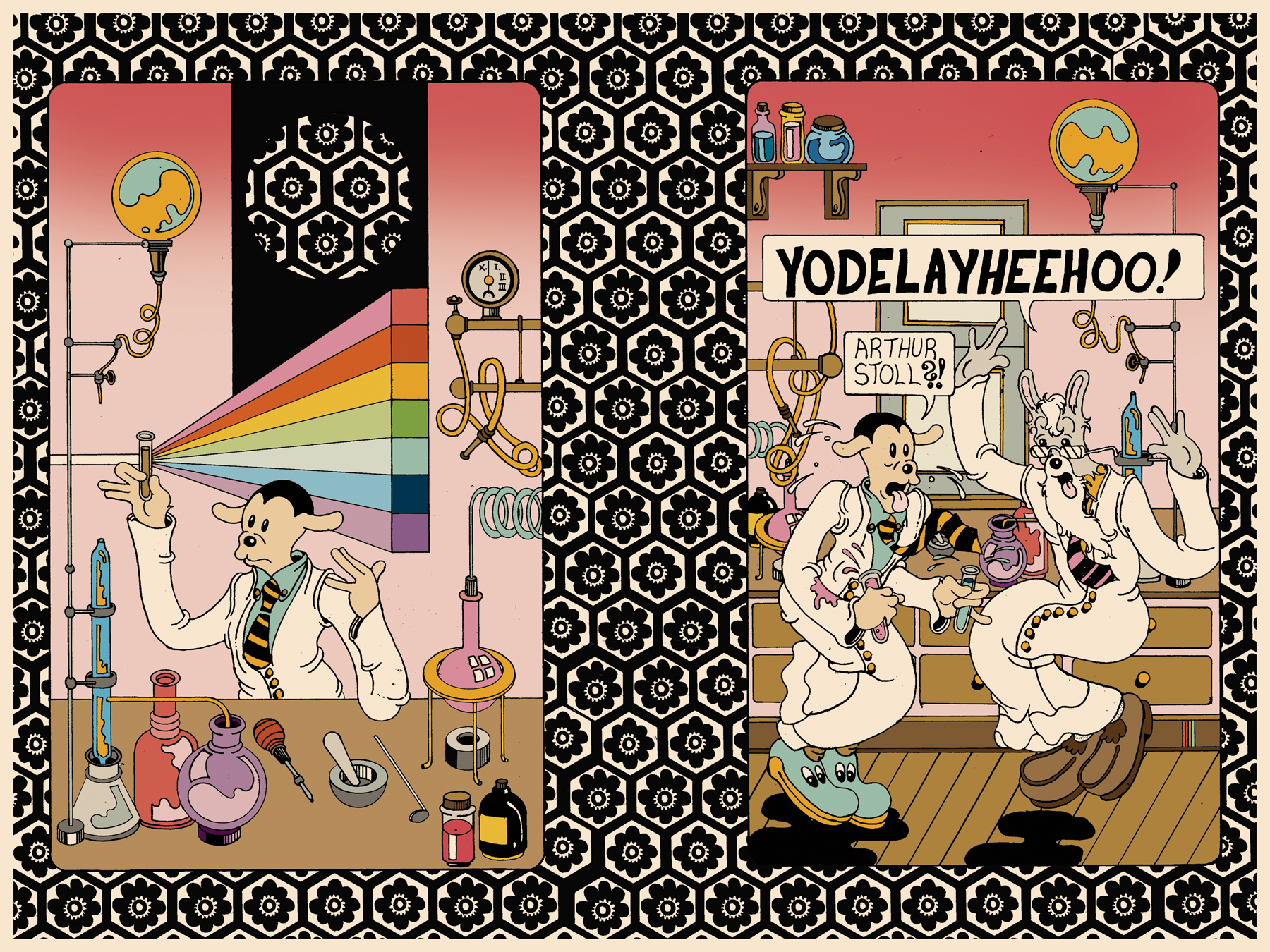

The story is legendary—and documented in Hofmann’s own words. But there are some details that Hofmann left out in his book, LSD: My Problem Child, that Blomerth reintroduces to the tale: including Susi (he deliberately leaves out her surname as it’s unclear why Hoffman never mentioned her in his book) the first woman known to have taken acid. Blomerth also champions “the real hero”, Anita Hofmann. The animalistic figures were inspired by visits to Prospect Park Zoo.

Hoffmann’s story begins in the late 1930s at Sandoz, where he was diligently investigating parasitic fungus. During those experiments he came up with LSD-25—aka acid. However, since it had seemingly no effects for the intended purpose, he shelved it.

It was only five years later, on 16 April 1943, that Hoffmann decided to return to the compound he’d synthesized. While concocting a new batch he became exposed to a small amount of the chemical; feeling nauseous and dizzy, he rode his bike home, where he had some kaleidoscopic visions and dreamlike hallucinations. Blomerth depicts Hoffmann lying on the sofa, the walls swirling with colours, as the voices of his wife and children drift in and out. Hoffmann wasn’t sure what had caused this experience, but he went back to the lab, and three days later purposefully took 0.25mg of his new batch of LSD-25—the most potent psychoactive substance that we know of.

“LSD is an example of all that is good about humanity: a triumph of science, curiosity, imagination, spirit and the unending search for meaning and truth”

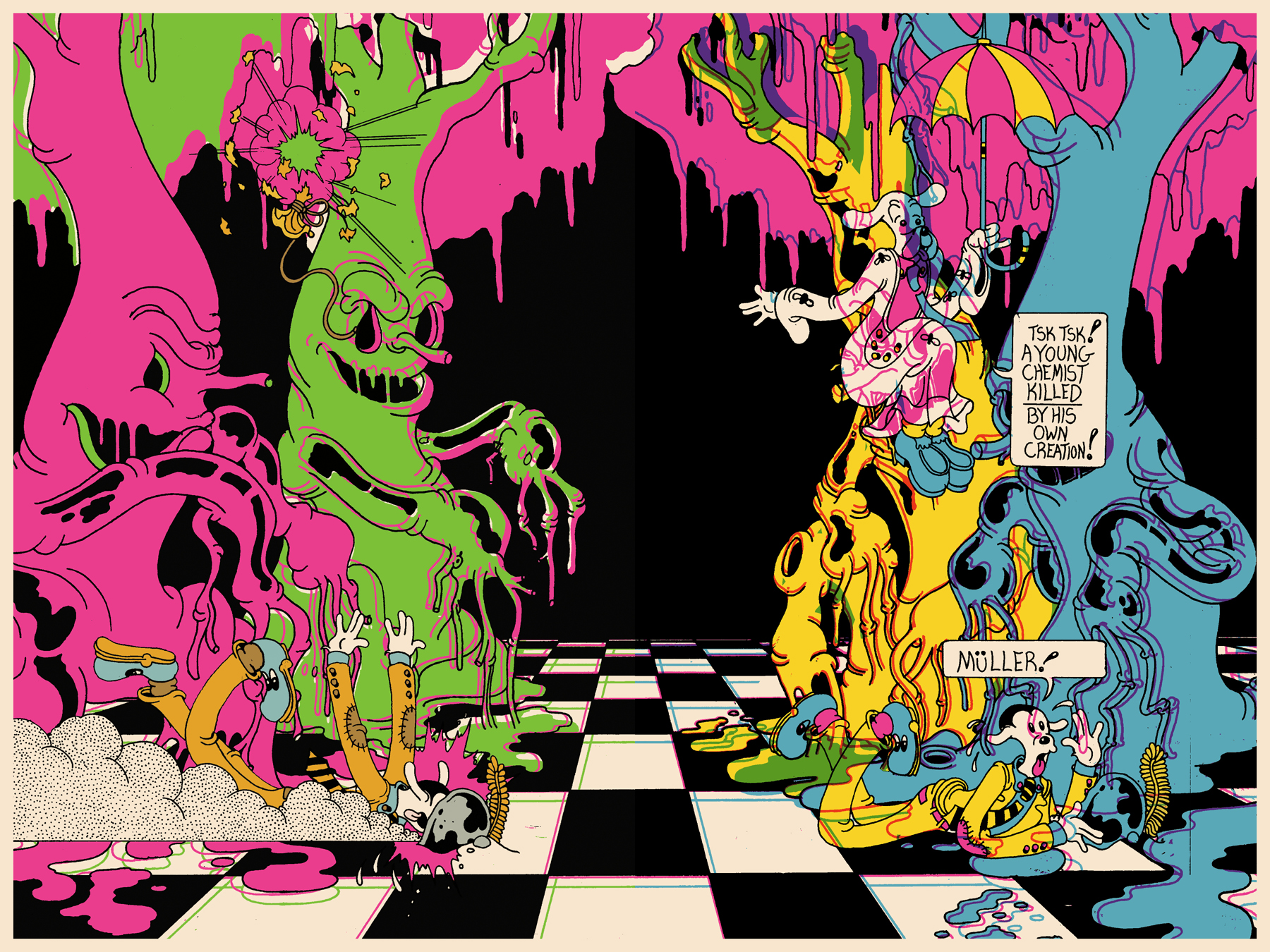

It was then, 19 April 1943, that Hofmann embarked on what would be the world’s first acid trip. Blomerth exuberantly illustrates, with a fluid, unstructured rhythm, mystical forms and raucous colours, an experience that was both revelatory and terrifying (Hofmann had visions of his own death) as reality melted away. It’s hard to imagine how Hofmann must have felt, not knowing what the consequences of his trip would be.

“LSD is an example of all that is good about humanity: a triumph of science, curiosity, imagination, spirit and the unending search for meaning and truth,” writes Dennis McKenna in the introduction to Bicycle Day that sets out the events of 1943. Both McKenna and Blomerth are unambiguous in their support of LSD—“LSD was a gift to humanity from the realm of the perfected archetypes, a gift for the future evolution of consciousness”—as McKenna puts it.

Hofmann always insisted on the safe and medical use of acid—not as a recreational drug, but as a form of psychotherapy that needed closer examination and study. Now, multiple organizations such as MAPS, Beckley and The Heffter Research Institute continue Hoffman’s legacy. The Heffter Research Institute receives a special mention at the end of the book from Blomerth, who gives a “personal endorsement”.

The same day that Hofmann was tripping—Passover Eve—the Warsaw ghetto was being seized by the Nazis. A month later, more than 56,000 Jews were murdered. Both McKenna and Blomerth bring these two events into parallel, demonstrating evil and the search to understand it. The discovery of LSD, McKenna writes, had the potential to be a “shining beacon capable of illuminating even the most obscure recesses of the human consciousness, a light of hope for humanity”.