Terence Nance’s film, An Oversimplification of Her Beauty (2012), tells the story of the male protagonist—played by Nance himself, and also named Terence—chasing the woman he loves, and of the miscommunications and bad luck that keep them from being together. Built out of an earlier film How Would You Feel? (2010), An Oversimplification is a blend of fact and fiction, as Nance embellishes real events and people from his own life.

The film is built of layers of uncertainty, as documentary sweeps from imagined narrative and live action blur into futuristic animation. “Your dreams are so powerful” says the narrator, “that you often miss things you never had.” As Nance plays with the line between creator and created in his attempt to find answers, our own uncertainty about reality brings us closer to Terence’s experience.

This attempt to find stability within uncertainty is a central tenet of Afrofuturism, the genre which centres the black experience through different and imagined realities. The archetype of the genre are the musical and filmic performances of American jazz composer, Sun Ra, particularly his 1972 feature film Space is the Place. Afrofuturism plays with past and future, fact and fiction, experience and imagination and throws it all into a celestial sci-fi space. It is characterized by colour, by pattern, by movement, by the integration of music and sound. The moon is a present and recurring character.

“Afrofuturism plays with past and future, fact and fiction, experience and imagination and throws it all into a celestial sci-fi space”

While Nance has said that he sees his work more as Afrosurrealism, there is no denying that Afrofuturistic elements are fundamental to his work and ever-present. It is also evident that their appearance paved the way for the aesthetic to move into mainstream explorations of Africa and the African diaspora in Western visual culture. Nance’s legacy is films like Sharon Lewis’s Brown Girl Begins (2017) and Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther (2018), as well as music videos such as Jay Z’s Family Feud (2017) and Janelle Monae’s album Dirty Computer (2018), which opened up the world of Afrofuturism to a far-reaching audience.

The Afrofuturist concern with space and time centres around the recognition that African Americans and other African diasporas are communities that have historically been erased and censored, until their pasts are obliterated and their futures uncertain. Loyal to Afrofuturism, Nance’s film blends past and future into the present, both in the narrative (particular moments are repeatedly returned to) and in the aesthetic.

The narrative is always darting off from chronological progression to look at experience from a new angle, like a cubist painting, where the aim is to get a sense of the whole by approaching the object from all sides, rather than perceiving things in the more limiting tones of realism. Space is a concern of the film in all its facets; Terence repeatedly refers to the fact that he has lost touch with the women he loved because they now occupy a different space, whether that be a new house, a new heart or another hemisphere.

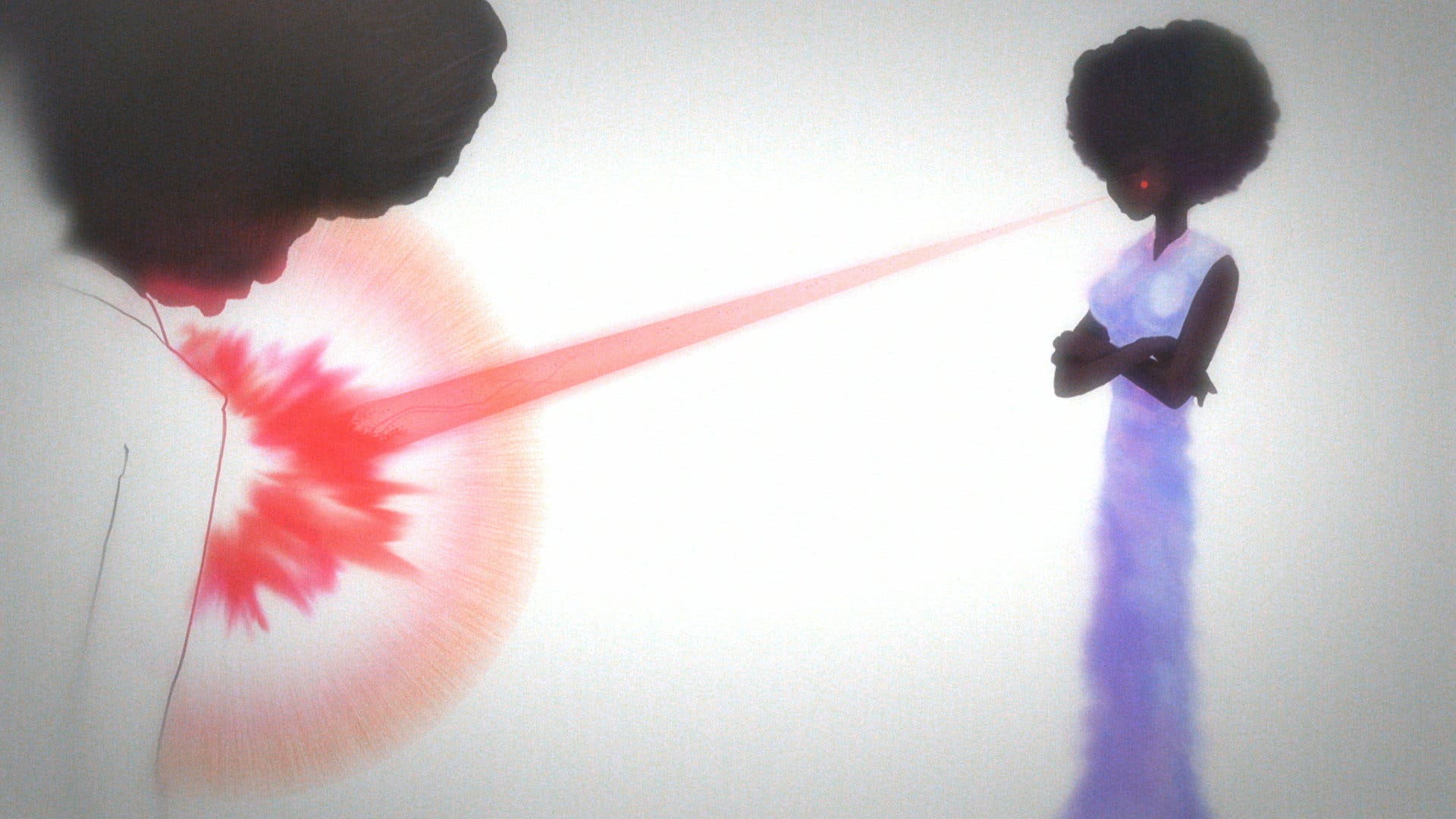

But Sun Ra’s assertion that “space is the place” is not ignored and the celestial aesthetic is significant. Nance’s animations visit the moon in their elation and fall through an infinity of stars when their romantic efforts are thwarted. After a descent through a visualization of the metaphorical void of heartbreak, Terence’s love interest fights off the love beams that shoot from his heart with her own red neon light sabre. Recently, Nance has ventured into music videos in a manner that would likely make Sun Ra proud, and his Afrofuturistic aesthetic continues to show in his art directing in Solange’s When I Get Home, and The Dig’s You and I and You.

Afrofuturism does not include just any film that centres the experience of a black person. At its heart is an acknowledgement of the alienation that black people have experienced at the hands of institutional racism, and privilege that has benefitted white people, for hundreds of years. It is a genre that carves out for black people the imaginative space that they have been excluded from historically, in a world that has been determined to leave them “out of sync”.

While it is not therefore intended for white people as such, it is as important for privileged majorities to pay attention to visual culture that does not centre them as it is for minorities to see themselves reflected. As the aesthetic and soul of Afrofuturism becomes more mainstream and finds new audiences, this can only be a good thing.