‘My work doesn’t come from the head. It comes from the heart.’ Bill Viola beams a beatific smile, hand raised like a saint. Sitting beside him, his wife and Executive Director Kira Perov leans closer, ready to interject if the conversation moves into dangerous territory.

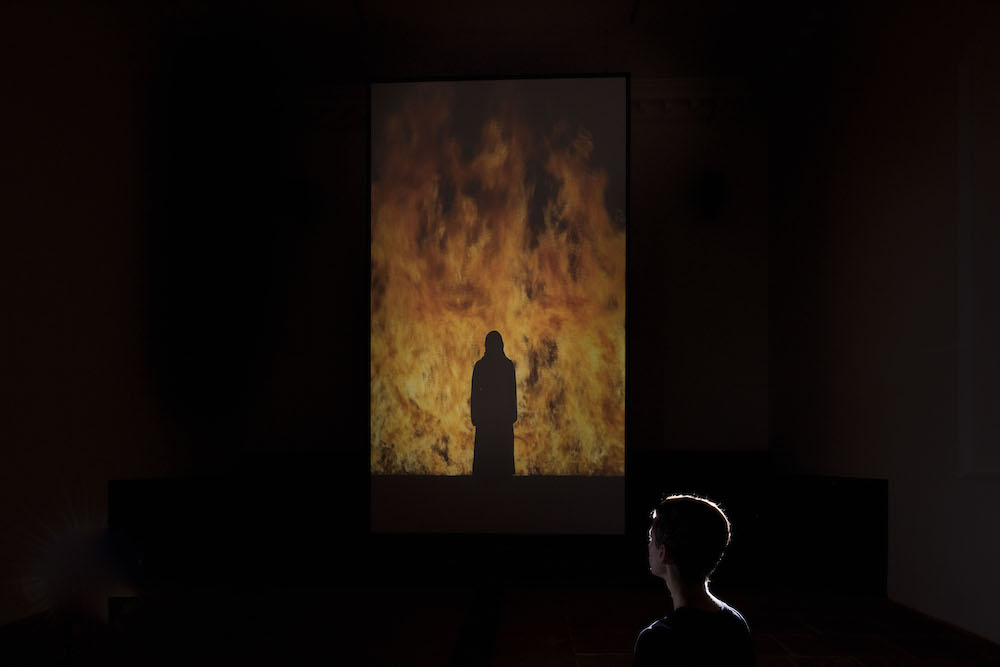

We’re at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, where the Underground Gallery has been transformed into a dark, labyrinthine hoarding of Viola’s video installations, charting his career from The Veiling (1995) to the premier of a new work, The Trial (2015). Across the park, the windows of the Chapel have been boarded up to contain the vast video projections Fire Woman and Tristan’s Ascension (2005).

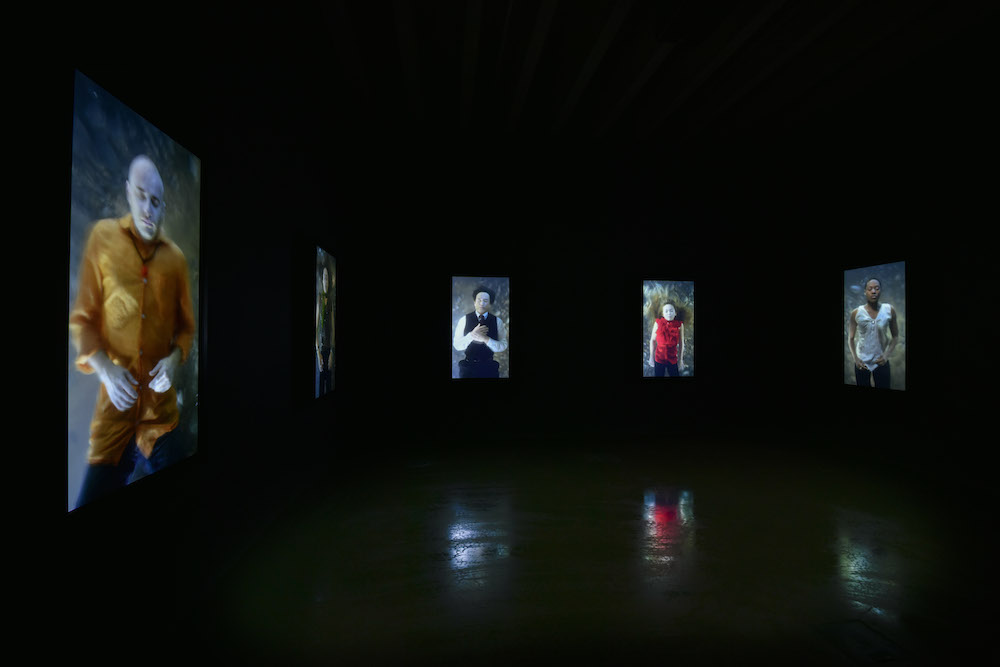

Viola was among the first to adopt the Sony Portapak in the late 1960s, becoming a pioneer of early video art. Living in Long Beach, California, he has all the technical wizardry of Hollywood at his fingertips – works such as The Innocents (2007), The Return (2007) and Three Women (2008) were created with the help of technicians from James Cameron’s production studio. Known as the Transfiguration series, these installations use grainy CCTV footage to reveal figures approaching unseen screen of water: they emerge, soaked, shocked and exalted, into high definition colour. Viewed out of context these films resemble a high-spec ghost hoax. Experienced on plasma screens in a darkened room, they convey a message which transcends the medium.

There’s not much space for spiritual visions in contemporary art — seraphic sincerity just doesn’t sell that well. Bill Viola is an exception to the rule. With parallel exhibitions at Blain Southern and The Vinyl Factory and his installation Martyrs (2014) enshrined at St Paul’s, his work taps into a latent desire for the sacred. Yet behind each screen is a logistical miracle performed by two women: Kira Perov, who promotes, protects and disseminates Viola’s work, and Studio Director Bobby Jablonski who carefully stages our experience of the work. The gallery spaces at YSP have been re-proportioned to create a mood of immersion; sight-lines and dark corridors open up dialogues between rooms and benches serve the same purpose as an altar.

These two women are integral to Viola’s success, but their role made me wonder whether a female artist could achieve the same recognition. A spiritual male artist is a sage. A spiritual female artist is a mystic.

We have a weakness for venerable visionaries, and male artists age better than women: Ai Wei Wei dominates at the Royal Academy, Lawrence Weiner holds court at Blenheim Palace, Frank Auerbach reigns at the Tate. That isn’t to say that a female artist can’t be treated with the same reverence — just look at Marina Abramovic. However, the grand old women of art tend to be classed either as eccentrics (Yayoi Kusama), controversialists (Lynda Benglis) or confessionalists (Louise Bourgeois). More often than not, as in the case of Paula Rego, they’re all three. Their spiritual counterparts are more likely to be found in art therapy classes, banished to the category of Outsider Art.

While the work of female artists is too often interpreted in relation the individual and the body (Dorothy Iannone’s ‘erotic spiritualism’ comes to mind), Viola’s videos attempt to encapsulate universal truth. Although he has confessed that his obsession with water arose from falling into a lake at the age of 6, his work is presented as elemental rather than subjective. For his installation The Dreamers (2013) Viola specifically chose performers with an affinity to water: a synchronised swimmer, a water baby, a diver. Under the gurgling, jellied surface of the plasma screen individual characters become an idealised forms. ‘Immortalised in video’, they resemble the beautified bodies found in Californian mortuaries.

Bill Viola’s work is undeniably moving. But it’s a very clean vision, achieved with much housewifery. If you want a spokesman for spirituality, you’ll call on a man. Next year, Mary joins Martyrs at St Paul’s. We’ll see what she has to say about the situation.

Bill Viola is showing at Yorkshire Sculpture Park until 10 April 2016. All images © Kira Perov, courtesy Bill Viola Studio