Can We Start Over Again?

“If you tell the truth, you don’t have to remember anything.”

—attributed to Mark Twain

I have sworn against writing about politics, even to friends in emails, because fact often champions fiction. I have also sworn that I would not publish a living person’s name, but might cheat.

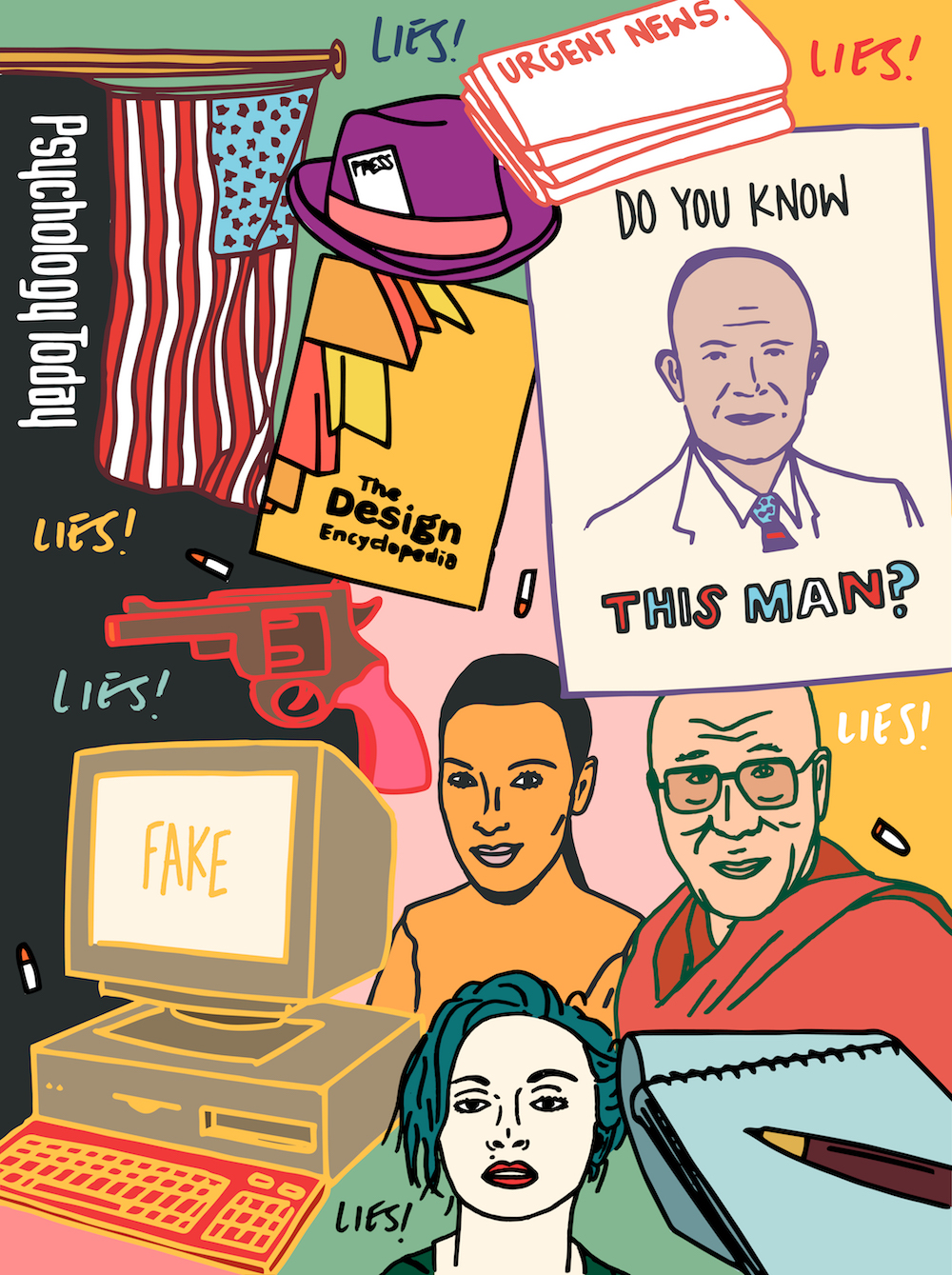

I am no different from everyone else, except those who live in a vacuum. I would live in a vacuum if I was not so impossibly nosey. Most of us know more about politics today than at any other time in history, even if we know just a bit about our leaders. Times have changed. In the 1950s, only about half of all Americans knew the president’s name—Eisenhower. Even then, probably due to his prominence during World War II. Mass media have always been blabbermouths. They serve a vast audience who want to know everything about everyone, from Kim Kardashian and the Dalai Lama to Madonna and Prince Harry. Gossip is better than sex, and it lasts longer.

About politicians: their obvious falsehoods are so outrageous that they induce yawns. Fact checkers will soon become unemployed because there are few true claims. And all CEOs lie too. In fact, everyone lies. Your parents have lied to you. If you want to stay married for a long time, you must fib often or wind up seldom or never getting laid. I was an inveterate liar as a child—even a thief. I once stole a toy gun from a neighbourhood child. The incident created a big hoopla that involved him, his father and my father. I swore I didn’t do it and stuck to my story. Thinking back on the incident, I don’t even know why I wanted it. I am sure it had something to do with hating or envying the neighbour, or some other mental disorder.

Was I exceptional in being crazy, or are all children crazy, whether they follow through on all their neurotic desires or not? Some psychologists claim that toddlers live in the right side of their brains where impulsive, emotional and nonverbal behaviour resides. The sutures or separations in our brains don’t fuse until about thirty-five, but even then, as you know, ridiculous conduct continues, particularly lying. The Western justice system is founded on perjury’s being a no-no, but we do it anyway.

Even though my mother was an angel, she told me a mountain of lies because she wanted me to know how life should be and what truth should be. Unfortunately, almost nothing was or is true. She broke every promise, or so it seemed, unaware that her son had an elephant’s memory.

One of my bosses, whom I had known for decades, lied about almost everything, and many knew his predilection, including me. I couldn’t figure out why. Then I finally realized that he was saying how he wanted things to be, not how they are.

At university in the 1950s for the school newspaper, I reviewed a just-published, important novel. I hadn’t read it and used information published in numerous high-profile magazines. My review didn’t confess that the criticism, positive or negative, was that of others. I could have easily written “Time magazine claims…” or “The New York Times argues…” If I had, my article would have been better. The toy-gun and the book-review incidents haunt me still. While not excusing these transgressions, they are minor compared to the plethora of false internet stories that have inured the public from believing anything except what it wants to believe.

I became a published professional writer in 1988. Since then, I have always written what I believe to be the truth. Of course, this is an absurd claim because there is no absolute truth. For example, if a law-enforcement officer immediately interviews on-site observers after an automobile accident, they will each tell a completely different story—so different that they might not appear to be about the same incident.

When I was ten, my mother remarried and left me with her sister for a school year. My mother chose to be with her new husband whose job necessitated travel. Because the incident was traumatic, I remembered for a long time that the hiatus was two years. It was one, and I visited her once during that period. I might have lied to myself on purpose to reinforce what I considered to be her bad behaviour.

When a historian writes about the lives of dead people, he or she is by definition re-retelling the recorded past, sometimes the long distant past. It’s obvious that no historian today has lived in the far distant past. When journalists write about people contemporary to themselves, whom they have never met, they often publish the information incorrectly, even though they might have called on audio recordings as notes. History books are filled with misinformation that is intentional. Throwing the truth asunder, US publishers (and certainly others) print various versions of textbooks to satisfy a range of local and national school boards.

Surely you don’t think that when I wrote The Design Encyclopedia for The Museum of Modern Art that I had had first-hand interviews with the hundreds of people I included? I simply scraped the data from a vast number of pages in libraries, including my own, that contained information from a vast number of other pages that held information from a vast number of historians—and so on. In addition to my disliking libraries because they’re boring, the problem with the process is that, when incorrect information is garnered from a historical account, the distortions, half-truths and fabrications spread like a pandemic virus. A prime example is that Charlemagne was illiterate. He wasn’t. In fact, he fostered literacy.

During the first edition of the Encyclopedia, a museum curator and friend saved me. He firmly suggested: “Mel, you must follow each entry with sources.” Fortunately, I had written only 20% of the book at the time. If I had had to return to a complete manuscript to include over twenty-five hundred bibliographies, I would have pulled my hair out. Much to my surprise, years since the book’s completion, I have discovered that many scholars and students are solely using it for its bibliographies. The practice does not displease me.

At one point, maybe up to twenty years ago, I told the brutal truth, at least as I knew it, most of the time. Then I discovered that the practice didn’t advance me at work, didn’t foster friendships and didn’t endear me to my relatives, who loved me but didn’t like me. They still don’t.

In “The Big Lie”, a 2014 article in Psychology Today magazine, psychotherapist William Berry points out: “Nietzsche expressed the idea that people need their illusions and that, when all is considered, they live in a lie. Even when people hear the truth, their defenses rise up and protect the ego against it….”

I ask friends to tell me that I’m sexy and adorable, whether it’s true or not.