Can We Start Over Again?

When I hear somebody say “Life is hard”, I am always tempted to ask “Compared to what?”

—Sydney J. Harris, American journalist

I retired a few years ago. Actually, I didn’t exactly retire. One day in 2015, at four in the afternoon, I abruptly stood up from my office desk, placed a few possessions in a carton, and took it to be mailroom to be shipped to my apartment in New York City. I then went upstairs and told the CEO: “Kiss my ass. Goodbye.” I was fed up with the corporate world.

While working as the manager of that company’s communications department, I interviewed graphics people, web designers, writers and others. I was forced to be “politically correct”, which meant that I couldn’t ask an applicant’s age, marriage status, address or interests. One woman complained about me to her employment agency because I asked if she had children, another for my asking where he lived. For God’s sake, if I hired them, we would be working elbow-to-elbow. In the interviews, I would sometimes cheat by saying, for example, “Unfortunately, I cannot ask if you’re married.” Inevitably, the person I was interviewing would then just tell me if they were married.

“There are eight billion humans on the planet; what possible secret could you have that at least millions of others don’t share with you?”

I have known people who have so many secrets that I’m sure they cannot remember them all. Why would anyone have many secrets? I have few. There are eight billion humans on the planet; what possible secret could you have that at least millions of others don’t share with you? Exceptions include murdering your mother—best to keep that one a secret.

Of course, publishing your secrets is a different matter entirely because that’s permanent. No erasures possible. So think twice. Philip Roth must be incredibly courageous.

Nevertheless, based on a request from the editor of Elephant, I will begin this column by revealing that I grew up in South Carolina, where I have now returned. I was a neurotic child. My mother’s friends told her that I was crazy and that I should see a psychotherapist or psychiatrist. I’m not sure that there were any in town then; there are now more than fifty. What goes around comes around.

I lived in a house with my mother and aunt, who were both single at the time. By the time I was ten, my mother had remarried, and I grew up in a trailer (or caravan). I never invited a friend to visit due to my social embarrassment. My mother, stepfather, two brothers and I moved every year from the time I was about fourteen to seventeen. The name for us was “trailer trash”.

I had one friend at a time, who was a loser like me. I subscribed to a number of magazines, read many books and consumed every page, more than once, of the fifteen volumes of Compton’s Encyclopedia. I was a real boy, even though no one else thought so. I collected insects, had an aquarium, saw a movie every week, lived the movie in my mind during the following week, was pointed out by teachers as being perfect which caused bullies to physically attack me, was determined to have revenge on them when I became an adult, hid a lot, was skinny and nonathletic, wore upscale clothes given to me by my Aunt Dollie, despised attending church on Sundays, had migraine headaches, incessantly listened to crime fiction on the radio and classical music on a 45rpm Bakelite record player, and rose early in the morning to avoid associating with anyone, even though I hated waking up early.

I left the mobile home at seventeen to live at a big university, where life was blissful. I discovered that I could be whoever I wanted to be; I didn’t lie, just didn’t volunteer the whole truth. All of my college friends were rich. During holidays, I would go to their homes, not mine. I loved the university, the professors, the library, the beautiful campus with redbrick walls covered with ivy. I acted in the theatre. When I visit the campus now, my eyes tear up.

Immediately after receiving a diploma in journalism on a very hot Friday in June, I left for New York City the next day on a train with about $700 in my pocket. Finding a job was difficult because my thick Southern accent was interpreted by snutty New Yorkers as meaning that I was stupid. I first lived in a home for old men and then the YMCA for $25 a day. No phone. Few clothes.

Manhattan was laidback when I arrived. Compared to now, it was a small city, even cosy. There were no $30-million apartments for sale then. My two-bedroom flat, with a 450 sq ft living room in one of the best neighbourhoods, was about $1,500 in the late Sixties.

My first job was with a college-book publisher. I wrote and designed brochures that were supposed to encourage professors to adopt textbooks. I never studied design, but I did make posters with Speedball pens as a child. The members of the family-held company were indifferent to the quality of the graphic design, but not to that of the writing. My boss indulged me. I was often late, and the timeclock calculator that stamped my card would not let me cheat.

I was so stupid that, for one of the brochures, I wrote “astrology” instead of “astronomy”.

Life moved fast in New York City. In 1962 I moved to another publisher, where I designed books by well-known people like General Douglas MacArthur and the Dalai Lama, who gave me a Tibetan flag. It is one of the very few of the zillions of objects I have been given or collected that I have retained.

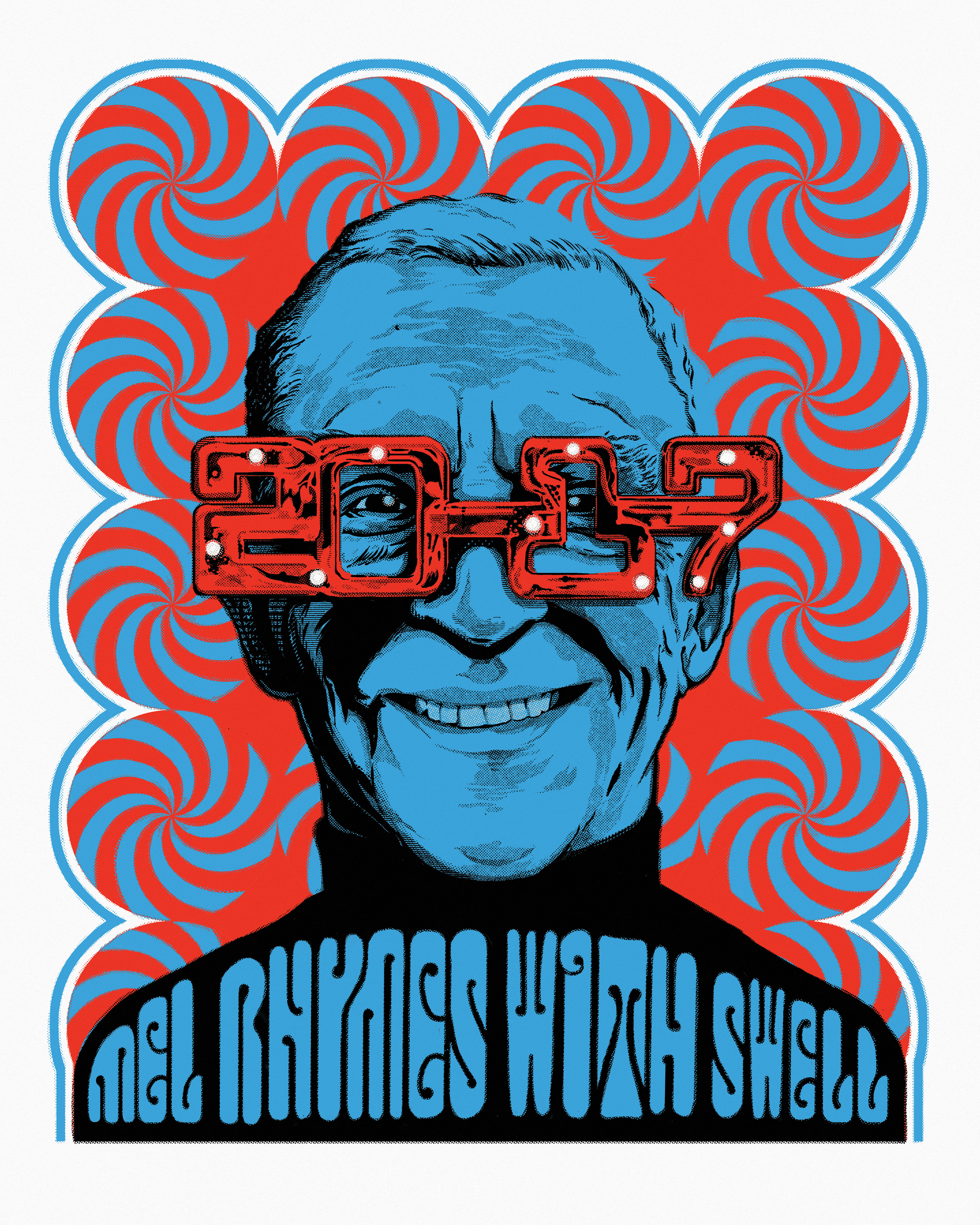

Becoming bored frequently, I would rent an apartment on a two-year lease, fully decorate it, and then, at the end of the lease, move on to another one. In the space of fifty-five years, I lived in possibly thirty different apartments, one with black walls, another with a kitchen floor in black, highly polished linoleum like in a Busby Berkeley musical. After moving and selling everything, I would buy more for the next one. I have been a collector forever: African art, period Louis furniture, lighting, Pop art when it was cheap, Chinese and Afghan war rugs, vintage photographs, a jukebox, vintage Herman Miller and Knoll furniture, endless possessions. As my salary increased, the pedigree of my belongings increased. I finally stopped selling and began gifting to museums in New York, Paris, Prague and even, recently, a collection of more than a hundred Sixties psychedelic, textually indecipherable rock-era posters to a museum in my hometown.

Actually, I didn’t and still don’t like rock music. I only listened to Thirties and Forties music and didn’t know about the posters at the time. It was a West Coast, particularly San Francisco, phenomenon. Living in New York City and working for book publishers and advertising agencies, I was only interested in Swiss design. The idea of words in advertising or posters that people cannot read would have been absurd to me—just as today. The rock-music artists were drugged hippies. Only one was female, the wife of the Fillmore Auditorium’s Bill Graham. They were not consciously selling anything. They were not propagandists. The images included are dotty, having no relationship whatsoever to the musicians—Edgar Allan Poe, Gloria Swanson, Santa Claus with horns, the Taj Mahal and Jesus. Much of what travelled from the designers to the final images on paper were with the appreciable intervention of the printers.

One of the two most prominent designers, Victor Moscoso, who studied with Josef Albers at Yale University, said he didn’t care if his posters were readable. (The other most prominent designer was Wes Wilson.) If you think that the phenomenon of the unreadable died after the Sixties and early Seventies, you are forgetting April Greiman’s messy scrapbook aesthetic and David Carson’s intentionally unreadable work, such as his so-called deconstructivist pages for Ray Gun.

(As an aside about psychedelic posters, I had a dream a few days ago that made me aware that they are all positive—no matter how silly. Nothing dark. Yet they were being created at the same time—late Sixties—as the youth protests in the US and Europe.)

“I don’t think that I and other obsessive collectors can explain ourselves. I don’t have much left except a hundred-plus examples of Navajo blankets that I am wishing to grant to an as-yet-undetermined institution.”

Serial collectors are strange people. I don’t think that I and other obsessive collectors can explain ourselves. I don’t have much left except a hundred-plus examples of Navajo blankets that I am wishing to grant to an as-yet-undetermined institution. (If there is a curator out there interested, speak up.) The rarest, most interesting gift I have made—at least in my opinion—is probably a quipu to the Israel Museum.

Back to my career. One art-director position followed another. One award followed another. I was not only an art director at publishers but also at magazines, small studios and large advertising agencies. For four years in the early Seventies I was the principal of a small agency/graphics studio with Hollywood movie-studio accounts. It closed due to my financial mismanagement. Lesson learned: I never again managed a company’s funds. And more generally: I never again took on tasks that I don’t do well, which includes my abstaining from financial matters.

Concurrent from the late 1960s, I was active in art. On some canvases I glued clothes and other objects. Others were grizzly, Fontana-inspired, with slashes sewn up and red paint oozing through them. Still other pieces were sealed Mason jars containing posters of famous art cut into strips. After about ten years I stopped because, as I have admitted, I often become bored. Most were intentionally destroyed. Only a handful now exist, including a frozen glove from 1969 filled with electronic parts, now owned by a Parisian collector, and a white lifesize sculpture in plywood, outlining a real person, with a red heart in a clear Plexiglas-box insertion.

Everything changed for me in 1988, when I broke my personal first commandment: “I will never live anywhere other than Manhattan.” By this time, about fifty of my friends had died of AIDS. I stopped excessive drink and recreational-drug consumption and moved up the Hudson River (about 50 miles) from Manhattan, made an initial visit to the furniture fair in Milan, spent some time in Paris, began teaching the history of graphic and industrial design, and started writing the first edition of The Design Encyclopedia. The Design Encyclopedia is my best accomplishment and was made possible by the publisher himself, Laurence King—twice. For the first edition, there was no significant internet available to help me appreciably with the research; therefore, much of it was garnered from books in a range of languages. Only an insane person like me with no advanced degree in the subject and no prior books published would attempt to write an encyclopedia. Laurence has claimed that he recognized that I was nevertheless capable. It is possible that he used a divining stick or witching rod. I was about fifty years old at the time.

I learned that writing nonfiction books will not make me rich; in fact, will make me poor. I learned that serendipity plays a big role in everyone’s significant accomplishments: I was relatively free at the time of the second edition, lived in Paris with a garden (the garden helped), and was meagrely supported by a small sum bequeathed to me by my stepfather. Possibly the biggest lesson I learned is that, because I become bored easily, I have quit a number of projects in midstream in my past—the cause of great but secretive shame, if one can be secretively shamed. The fact that I persisted with the first and second editions of the encyclopedia to their very end—and I emphasize “very end”—somewhat absolved me in my mind. And when, in the introduction to the second edition, Terence Riley, the head of MoMA’s design and architecture department at the time, called me the Diderot of design, he closed the door on my quest.

Being awarded the Besterman/McColvin Gold Medal for best reference book was momentarily thrilling, but the excitement soon faded. And, by the way, I have lost the medal—cannot find it anywhere. Besides, what would I do with it? Certainly not wear it or place it on display.

Some people at a prominent enterprise recently hired me for a project because they had been told that I am the ultimate authority on design. Can this be true? Of course not.

Remember my mentioning that the world’s population is about eight billion? If there are those out there who believe that they are the ultimate or the best at anything—or better than anyone else—please contact me directly, and I will refer you to a psychiatrist like the one to whom my mother never took me.