Rose B. Simpson speaks to me from her immutable home within the sun burnished landscape of her tribe’s terra firma, otherwise known as the Santa Clara Pueblo. This historic area of the Pueblo people has existed for thousands of years; sustained by the waters of the Rio Grande and now abutted by the New Mexico capital of Santa Fe on one side, and the notorious city of Española—known as the Lowrider car capital of the world—on the other. As we’re talking, Simpson’s three-year-old daughter can be heard playing in the background, adding her own charming narrative to our conversation as we discuss Simpson’s recent successes.

One of these notable accomplishments is her current exhibition Duo, currently on view at Jessica Silverman Gallery in San Francisco. When I ask Simpson about the impetus behind the show, she describes the importance of site specificity to her work: “I was thinking about audience and space. I wanted to see an arrangement of bodies facing each other in a line, as a way to formally display relationships and activate the space between,” she explains.

“The sculptural couplets elicit both the tension and fecundity of co-existence; the ability for beings to work together or against one another”

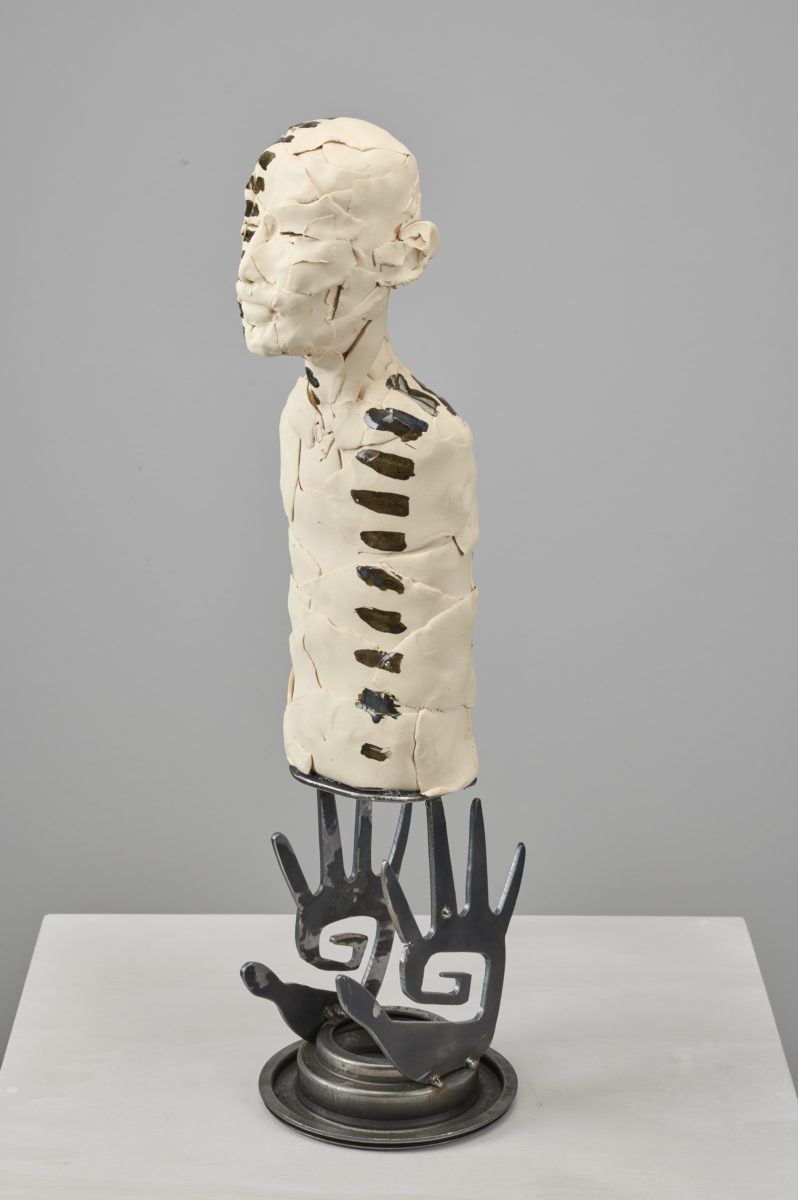

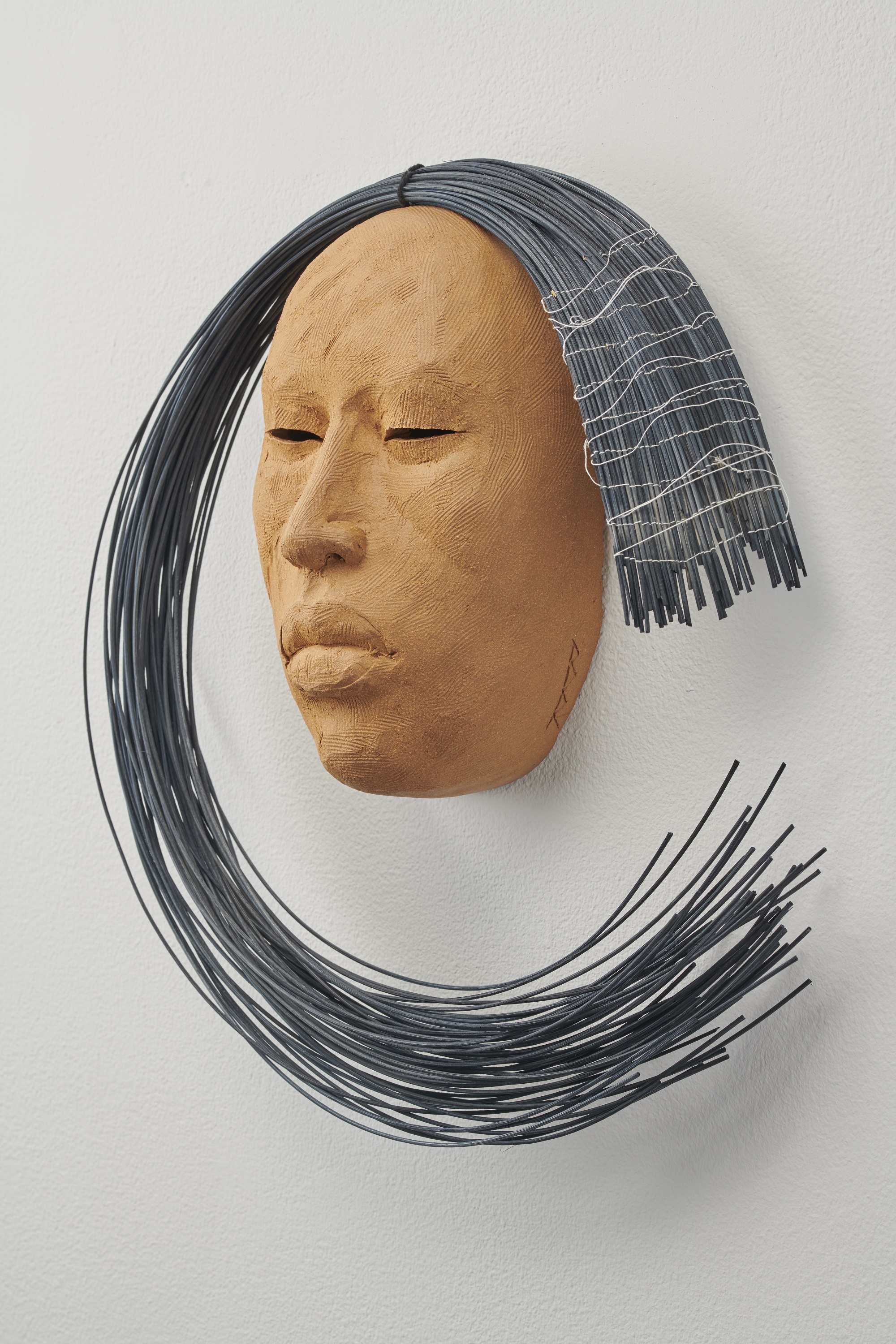

Eleven sets of genderless corporal sculptures, some evoking totemic forms, others akin to funerary masks, can be seen in the exhibition. The colours and processes hearken back to Simpson’s own Pueblo culture and her tribe’s venerated practice of creating ceramics and pottery. Simpson, along with her mother, Roxanne Swentzell, is among several Santa Clara sculptors whose work has received global recognition.

While each set of bodies in Duo consist of a double, they are not parts of a whole, but rather mutual individuals—equals with a common identity, twins navigating the world simultaneously but alone. The sculptural couplets elicit both the tension

and fecundity of co-existence; the ability for beings to work together or against one another. Simpson informs me that, though she created each work as doubles, they are sent into the world as single pieces.

These can be purchased individually or together, therefore bestowing a weighted decision on the collector: “If someone buys one of them, they’re responsible for the splitting of the work. To me, that adds to the conversation,” she asserts. The twinness of the works is key; they are birthed together, but through circumstance have to navigate the world as solitary beings.

Simpson’s bodily forms are evocatively tactile, with the trace of the artist’s touch remaining strikingly visible on the ceramic surface. This is due largely to Simpson’s idiosyncratic process of furiously reworking the clay’s density. With a method she calls “slap slab,” she repeatedly throws clay onto a diagonal surface until the material is paper thin. From here, she applies an additive process to build up the body of the works in wafer-like strips, which come together to create the solid somatic form.

It could be said that Simpson’s work is ultimately about the human

condition. Her identity as a Native female may be in danger of becoming fetishized, but for the artist, her work exists within a far less prescriptive state. Simpson is forced to grapple with cultural insensitivity, but ultimately she sees the fight against the racial determination of her work as a privileged engagement: “I’ve had a lot of access because of these cultural fixations, which I’ve had to navigate in strange ways because the work that I do within the Native art sphere is considered weird and unheard of. Also, because I’m sensitive not to overshare or capitalize on my identity, I’m able to have a deeper conversation about humanity. Some of the decisions I’ve made are intentional to deconstructing the stereotypes around culture and gender.”

Our discussion of gender inevitably leads to a discussion on Simpson’s predilection for automobiles, and her active involvement in car culture. This obsession goes so far that she even formally studied Automotive Science at the Northern New Mexico College (she graduated in 2015), subsequent to receiving her formal art training at the Rhode Island School of Design and the University of New Mexico. With its built-in velocity and utilitarian economy, Simpson treats cars as a vessel in much the same way as she does her ceramic sculptures.

“Where Simpson comes from, cars are emphatically celebrated as symbols of pride, and as a means of survival”

Earlier this year Simpson installed Maria, her custom built 1984 Chevrolet El Camino, within the Minneapolis Institute of Art, as her contribution to the group exhibition Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists. The car’s moniker pays homage to Maria Martinez, a Native potter of the San Ildefonso Pueblo, who painted using a distinct black-on-black technique. It is a process that continues to be implemented by Simpson’s tribe, whereby alternating matte and polished treatments are used to create geometric and figurative imagery. Simpson applied this technique to the body of her El Camino, painting swift geometric lines of glossy paint across the car’s paneling.

For Simpson, this use of automobiles within her art is a way to speak to her identity through means that eschew stereotypical mores. Rose explains how the car culture of Española suffused her upbringing (the artist bought her first car at the age twelve.) Where Simpson comes from, cars are emphatically celebrated as symbols of pride, and as a means of survival.

When I ask Simpson why she chose to continue to remain on her tribe’s reservation while pursuing a career as an artist, she explains the nature of her Native spirituality, deeply rooted in a sense of place: “You can’t go somewhere else and practice our indigenous religious belief system. I was raised very strongly in my traditional beliefs at the Pueblo, and because of that, to leave is to make a choice that is too hard.” This fidelity speaks to Simpson’s uncompromising nature. Simpson communicates her identity with reverence, and with a sanctity for its secrets.