British artist Simon Starling and Japanese curator Yukie Kamiya first worked together in 2008, when Starling was beginning to explore Henry Moore’s Atom Piece, housed at Kamiya’s then place of work, the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art. The pair have most recently worked on At Twilight, at New York’s Japan Society Gallery.

Kamiya is the recently-appointed Gallery Director at the Japan Society, and At Twilight, is the latest gallery stop for Starling’s ongoing exploration of Japanese Noh—via W. B. Yeats’s 1916 play At The Hawk’s Well, which took inspiration itself from the traditional theatre form. This Summer, Glasgow’s The Common Guild presented the artist’s re-interpreted performance of At The Hawk’s Well, which is documented in At Twilight alongside many sources of inspiration for Starling, including Brancusi sculptures from the Estate of Constantin Brancusi and works from New York’s Museum of Modern Art, The Noguchi Museum and the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College.

I spoke to Starling and Kamiya as planning for At Twilight was underway.

Can you tell me a little about your first points of working together, and how that’s developed over the years?

Yukie Kamiya: I first visited Simon in Denmark in 2008. I knew his practice and I really wanted to work with him. I went to meet him in his studio without any kind of particular idea and the conversation started. Simon already had a great idea, he had been working around the Henry Moore sculpture at Hiroshima [City Museum of Contemporary Art] and he was interested in researching this artist at the museum. We had one sculpture that was the trigger to start the project [Atom Piece, 1963–5].

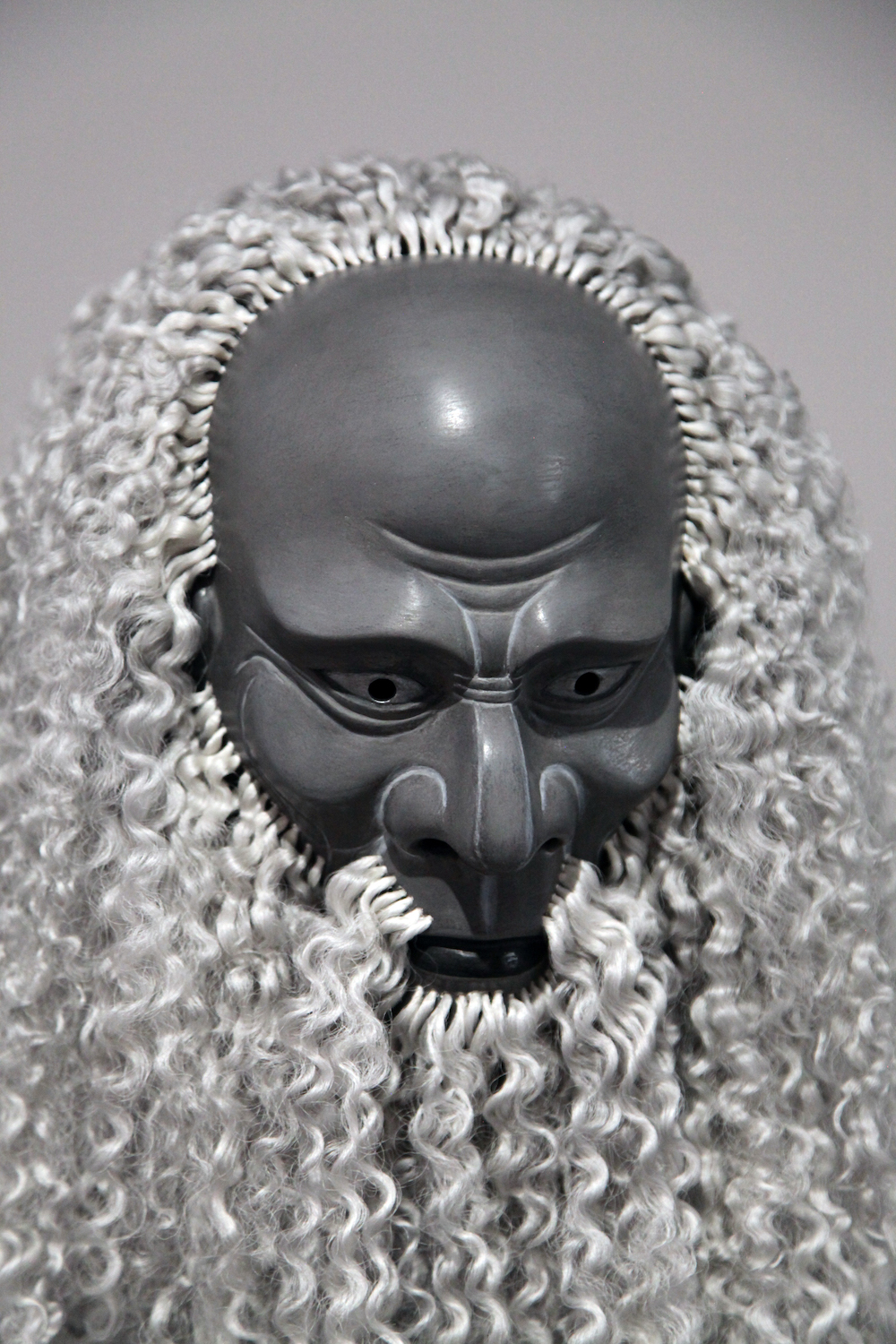

Simon Starling: In a way, the Henry Moore hits you when you arrive at the museum immediately. I started to hear these stories about the kind of odd, ambiguous status of this Atom Piece sculpture inside this big collection and people seemed almost a little bit spooked by it. There was a sense of, I don’t know, trouble or anxiety that seemed to surround it as an object within the collection. I started to dig a little bit, with Yukie’s help, and found out about this situation in the 90s which had arisen when somebody had published a newspaper story about the Atom Piece’s connection to the Chicago monument [Henry Moore, Nuclear Energy, 1965] for Fermi’s Pile No.1—the first sustained nuclear reaction, which was the beginning of the atom bomb project essentially. The question was: Why would a Hiroshima museum spend their money on a piece which celebrated the atom bomb project? So from there this project began to emerge, and the idea of working with the form of a masquerade. There was this sense that the sculpture had two names, but also a double identity in a way. And I linked this quite quickly to Japanese Noh theatre, where nobody is who they seem because of the masks, and gender shifts, and ghosts becoming human form. So it set up an interesting dynamic for me between the Cold War drama surrounding the creation of Henry Moore’s monument and its reception in Hiroshima. That was the beginning of my interest in working with Noh theatre, and Japan in general. It’s nothing I’d really touched on before and it was a long process.

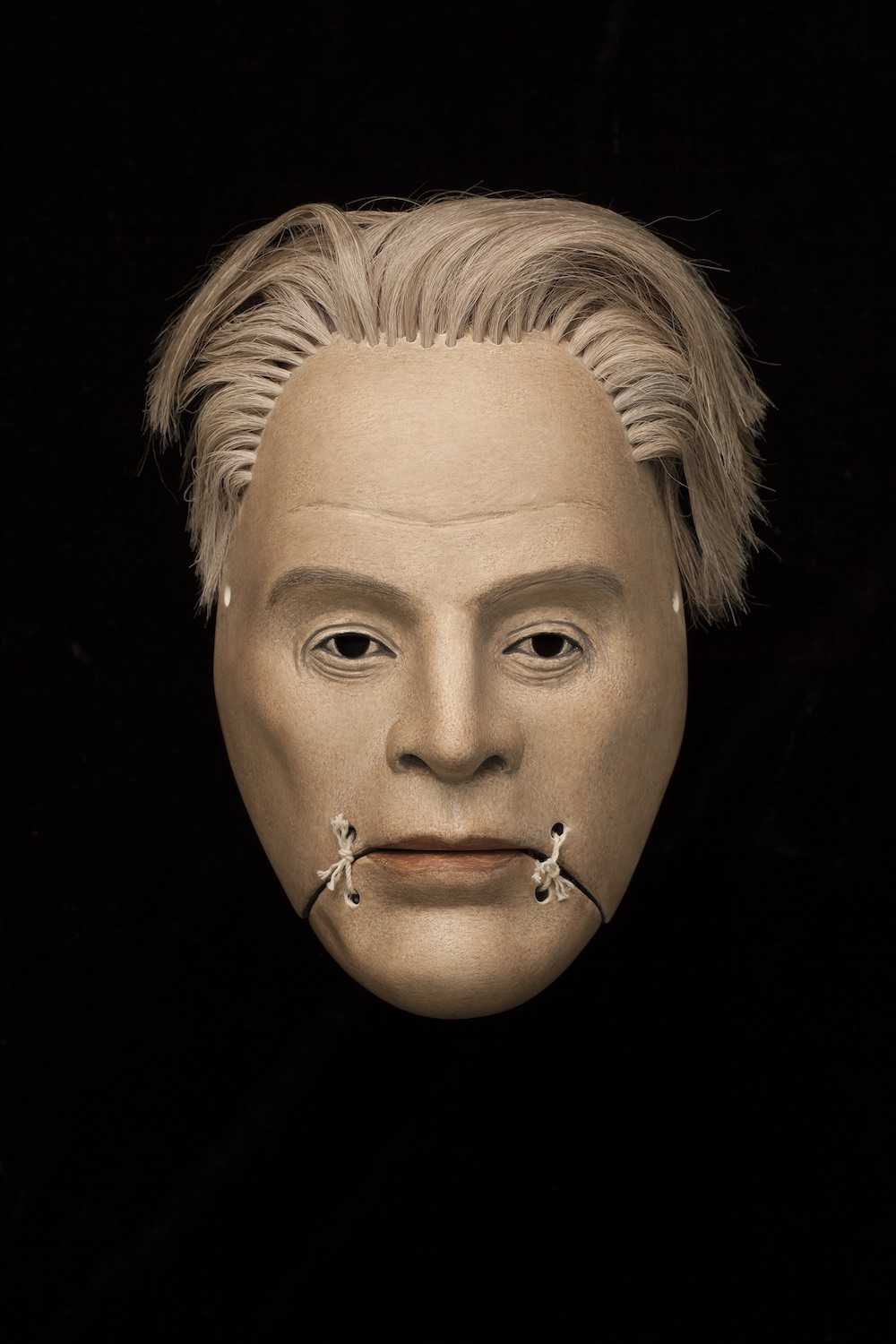

Yukie connected me to this Noh Mask maker, Yasuo Miichi, who eventually we persuaded to dive in and get involved in this madness we were proposing. We established a very interesting and rich working relationship with Yasuo and he started work on a series which I sent him designs for, and discussed with him when I visited his studio in Osaka. At that stage Project for a Masquerade remained a proposition for a piece of theatre—an almost impossible piece of theatre perhaps—that started conversations about the idea of actually putting something on stage, which is sort of where we are at now. And I had conversations with Yukie about that, but there were other people who saw the project too, and one of those was Katrina Brown who runs the Common Guild in Glasgow, she pushed a little bit, and eventually I said: Well, maybe not Project For A Masquerade, but perhaps this story of W. B.Yeats and Ezra Pound and the 1916 absorption of Noh theatre into European Modernism, which was a moment I came across when working on Project for a Masquerade.

YK: Simon had the idea that the story starts in Japan, you come from a very specific form of Japanese Noh, but all the inspiration is the dialogue between Simon and the Noh mask maker —who is in a different field but still a creator—and then this kind of dialogue in the next stage which jumps into Yeats and At The Hawk’s Well, so all of these links are beautifully connected. And it’s been great to see as the exhibition organiser.

SS: And then when Yukie moved from Hiroshima to New York to pick up the post at the Japan Society, she approached me again with the idea of bringing the project from Glasgow to New York, and that’s what we’re doing now in a very specific and I guess appropriate kind of context. I’m one of the first non-Japanese artists to make an exhibition at the Japan Society—a rare beast!—so it’s almost a little nerve wracking. But in a way, making Project for a Masquerade in the first place was a bit of a gamble. To take that to Japan and present it to a Japanese audience… probably a little like W. B. Yeats, if I’d known too much it would have been impossible. Certainly Yeats’s engagement with Noh theatre was extremely superficial in a way. It was about capturing an essence or a style, something of the manners of it, but he didn’t understand it in a real way, and I think if he did it would have been something very different. So there was a little sense of trepidation when I presented the work in Hiroshima, but the response from Japanese people was extremely heartening. There was a sense, especially from younger Japanese people, who said: We’re really happy you’ve done this, it isn’t something we could have done ourselves. And that was quite exciting. It was a risky thing to do, a foolish thing, perhaps! But I think it worked.

YK: Well your processes are very like Yeats’s, but it’s also great at the Japan Society to connect you with Japanese culture. It’s always a challenge of how we can break the stereotypes and it’s always with new imagination, new interpretation, and it could be some misunderstanding. But those kind of in-between ideas create a very new point of view, which Yeats did, and you do Simon. So that’s one reason the Japan Society, in the global age, asks from another angle how Japanese culture in a global view is inspired, adapted and changed. Simon discovered this moment from 100 years ago, so in some way it’s all come together—magically almost.

SS: For sure there’s a sense of parallel. One of the interesting things for me in the 1916 moment was the collaborative nature of it, and the cross-cultural moment of it. So an American poet, an Irish poet, a French illustrator and a Japanese dancer all get together and stage this hybrid piece of theatre in London during the First World War. It’s an irresistible conflation of different forces somehow. And that’s very much what we’ve tried to create in 2016, working with a South American choreographer, Javier De Frutos, and a Chicago-Based musician, Josh Abrahams, and an English theatre director, Graham Eatough etc etc. It’s been a similar kind of construct. It’s really a kind of complex collaboration and I think you feel it immediately in the objects. I realised also looking at the exhibition at the Common Guild, it’s an accumulation of time. It’s been evolving over years and also it connects to another time, and another time again. And it’s all there embodied in these actions and texts. It’s a very dense kind of construct I think.

YK: And in New York, because of the location we’re lucky to be surrounded by a variety of museums and institutions, so we approached them for the ideal pieces of modern art from which Simon got the inspiration for the masks and story. So Brancusi’s sculptures are coming, a portrait of Michio Ito, and those kind of juxtapositions could create some kind of mind map of Simon’s thoughts to connect people between the different times.

SS: And also to embody the moment that was created in At The Hawk’s Well, that modern moment in 1916 which is extraordinarily well-represented in American museums. It was a very rich palette to draw from.

How will this part of the project be displayed at Japan Society?

SS: I guess the exhibition is an attempt to bring a rather complex project to a gallery situation. It’s a project that exists as objects and costumes, a text and also has a very complex historical frame. We’re presenting a reconstruction of the stage situation which [was] present in Glasgow, and there will be the Hawk Dance film which is part of the live theatre experience. The architecture of the Japan Society has a sense of the bridge-way that connects these two galleries. So the area of one gallery is demarcated as the stage, and then there’s this bridge-way which is connected to a smaller room which will be used as a notional dressing room where some of the costumes from the play will be exhibited in front of a mirror. The third room, which is sort of the antichamber to the rest of the museum, is where the historical material will be. That’s the structure of it.

When you’re working with a culturally specific institution do you feel the process is different to when you create a show for a more traditional art institution? This might be the way you work as an artist, or your relationship in developing a project?

SS: It hasn’t been hugely different, and any institution, whether it be culturally specific or not—I mean every institution is specific in one way or another—they all have their particular ideas they want to project, another set of permitters to negotiate. As an artist I have always been quite proactive in the mediation of my work and what you might call the pedagogical aspect of the reception of an exhibition has always been of interest and something I’ve tried to be involved with all the way along. So that’s always been a negation in a way, finding a common ground in how that could be done. But it’s been a nice process and a learning process too.

YK: Our name is culturally specific, and we have differentiated between photography, print, contemporary and the different periods in the past, which kind of makes fragments within the museum, but now we try to create for an interdisciplinary interest, to get beyond the old definition of cultural specificity. It’s always a big challenge with artists and Simon’s practice has really been a gateway. This presentation, for the first time in the US, of his latest project is really a good way to identify the new idea of the culturally specific institution.

Often taking inspiration from another culture raises questions of cultural appropriation, which is something that doesn’t come up with your work Simon. Do you think there is a certain structure for working with another culture, other than your own, that pulls it away from discussions around appropriation?

SS: Well it’s a very transnational endeavour I suppose. One of the very nice things that’s happened to Yeats’s play is that it’s been re-appropriated by the Japanese, and Yukie and I visited a very important Noh master, who is developing a very traditional reworking of his play currently, and it’s really being reabsorbed back into the Noh canon which I think is fascinating. It’s taken a 100-year detour via Modernist Britain and it’s been an important text as a way to test and modernise Noh theatre. So it’s an interesting re-appropriation that’s come full circle.

YK: There’s not only the impact to the west through Yeats, the play was also shown in the 1930s in Tokyo and Noh-related people were fascinated and tried to get better than Yeats! It’s a stimulator for the traditional Noh theatre. It’s always that the inspiration is in a circle, where the inspiration goes back and forth.

Do you see this as the culmination of work from the project, or can you imagine that it will carry on developing for years to come?

SS: I don’t know, it doesn’t seem to stop! Not so far anyway. From the Hiroshima exhibition onwards it’s growing and sprouting shoots as an interest and a concern within my work. So I can’t see it being the end of anything no.

YK: To be continued…

‘Simon Starling: At Twilight’ runs from 14 October until 15 January at the Japan Society Gallery, New York