As visitors enter Rebecca Ackroyd

’s new solo show at Peres Projects in Berlin

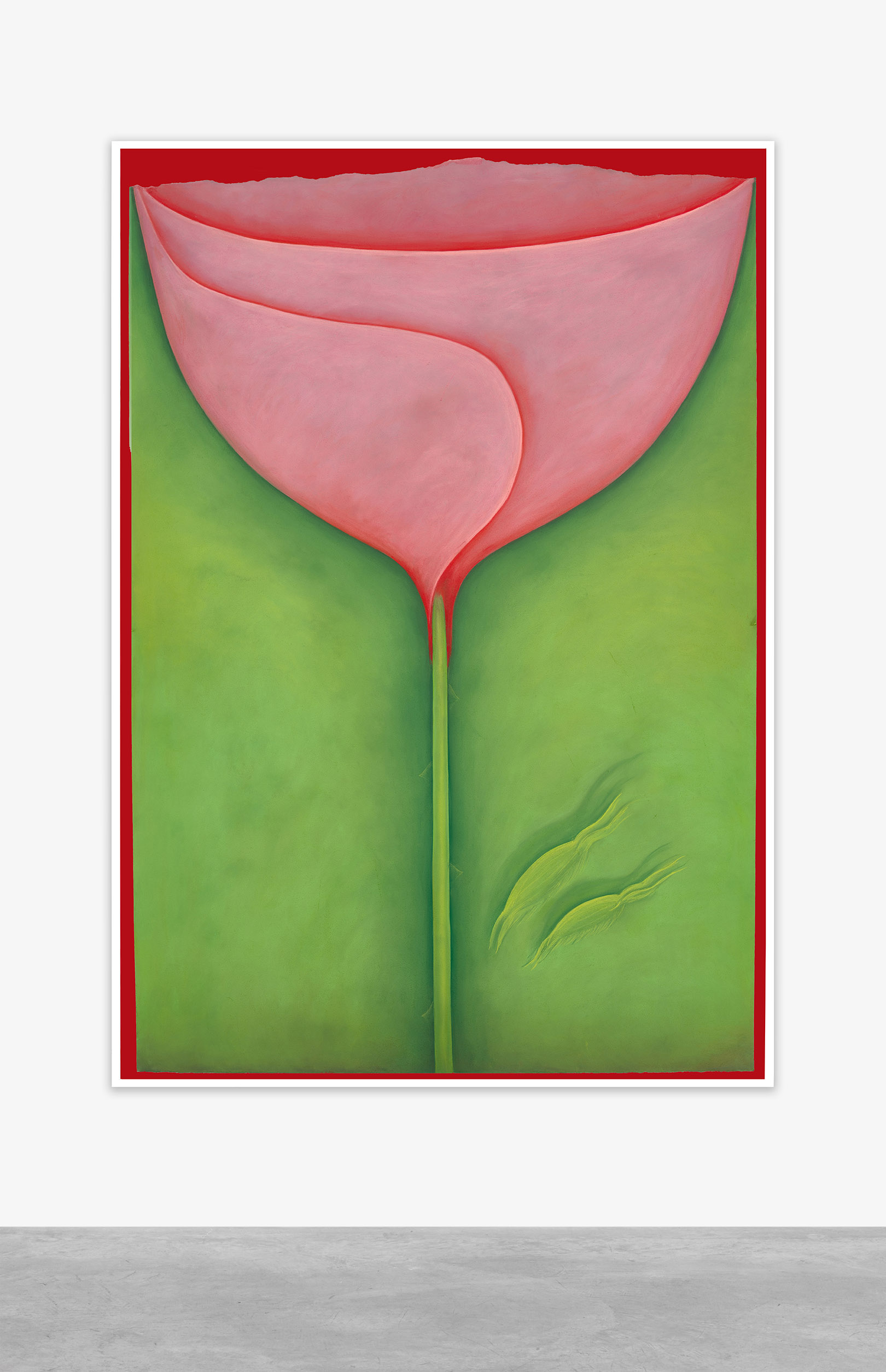

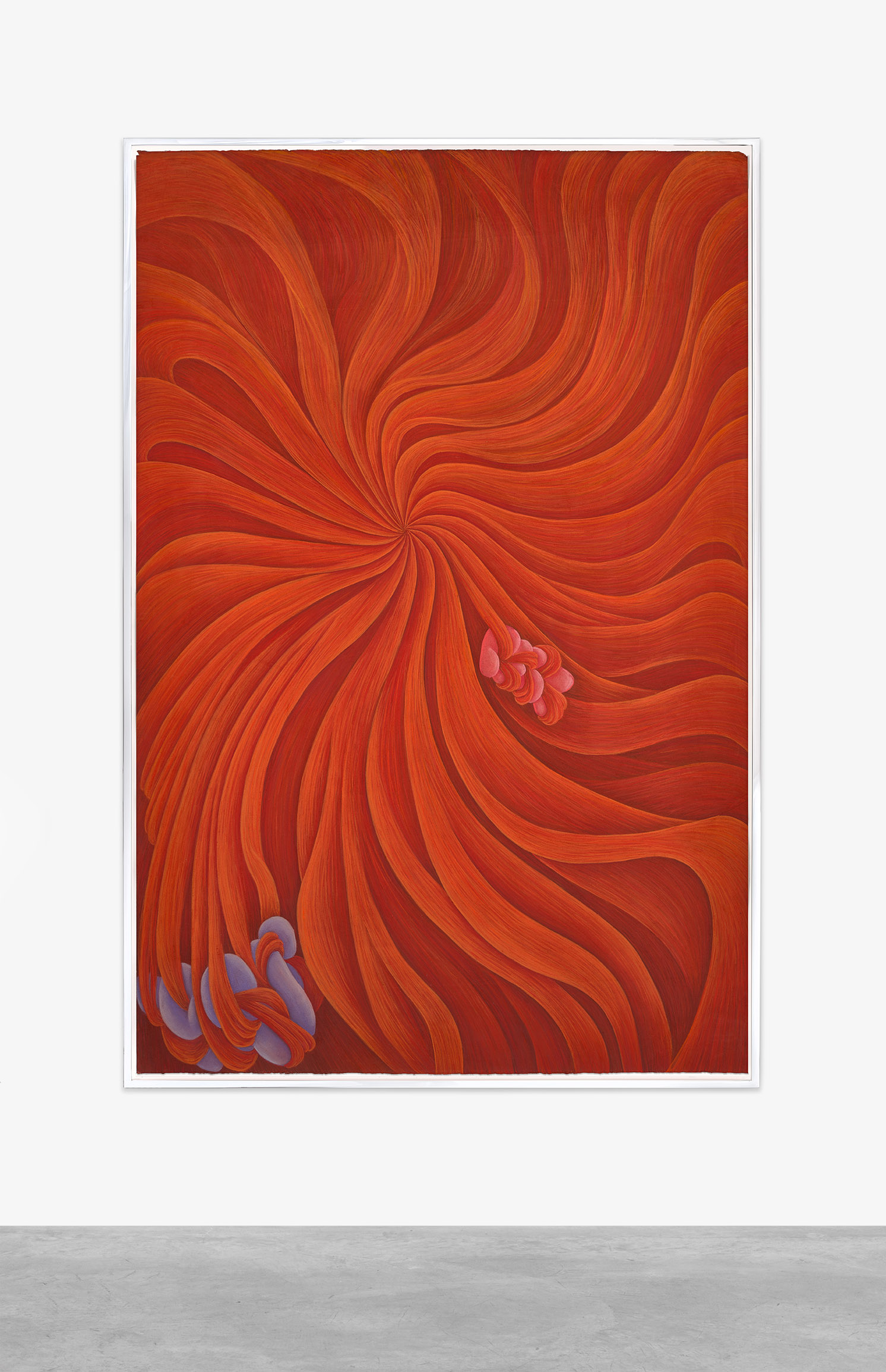

, they are met by a violent red mask, which covers the floor-to-ceiling windows that face out onto Frankfurter Allee—a Sovietic boulevard that serves as a reminder of the once-divided city. This red hue makes the space feel tighter and darker than usual. As my eyes adjust I find myself delicately stepping between ghost-like alien figures that are lounging around the gallery. The origin of such forms is unclear, they could be from the sea, space or even the future. It feels like these figures are either in purgatory or basking in a realm of fiction that only the artist knows about. It is uncertain whether this is a hostile or welcoming landscape, but it seems frozen in time. The narrative of timelessness is taken further by Ackroyd’s decision to turn the gallery into a waiting room, or perhaps more aptly a corridor, as she has hung shuttered doors on certain walls, begging the question, What lies beyond? Another world? Nothing? Everything?

This notion carries through in one of the adjoining rooms, which has been carpeted for the occasion with an old-fashioned floral pattern, complete with a drain cover. Occasionally you run into large cartoon-like drawings of flowers, or hair mutated slightly by unidentified mammals that seem to be squatting in the folical landscape—jelly-like, they burrow into thick human locks. The whole scene seems at odds with itself. As soon as you begin to piece together a narrative, it falls apart. But this is exactly the way Ackroyd wanted to present the show: “I was thinking about how ‘mulch’ was an apt description for the current time and the general confusion socially and politically. I wanted the show to resonate a sense of chaos by showing multiple works that don’t necessarily correspond to an overarching ‘concept’ or idea.”

This seems to be accomplished, but one can’t help wondering, isn’t this chaos the exact reason we cannot move forward, and by creating a show that has no tangible reading, is Ackroyd merely adding to this standstill? On the other hand, a viewer always comes with their own interpretation, which often deviates from the artist’s intention, so by saying there is no conceptual link one opens up every angle. This sense of performed potentiality seems to resonate within the structures too. Not just in the faux doors, but also the way in which the alien figures have arches and windows cut into their bodies. They are offering passageways through their ribs, knees and groins, creating deep red tunnels. Ackroyd states again, there is no time, genre or spatial identity to these figures. In essence, she merely “wanted them to feel contemporary with the choice in goggles, helmets and glasses” and “was loosely thinking about a church-like architecture in terms of their forms, but wanted them to exist in their own time and space”.

She goes on to explain that “the idea of a potential landscape is really important in my work; how space can become transportive and direct how someone might encounter the works is something I consider carefully. I’m interested in how specific objects or images can become signifiers from different environments, both urban and domestic, and also how these can then point to a sense of identity or, with the pub carpet I have used, national identity.”

“I wanted the work to reflect a layered identity and personal lineage of names, both inherited and lost”

The works on show seem to be constantly battling with the challenge of being personal and abstract and the space seems very emotionally charged. You feel the artist’s touch, throughout. “I often reference a personal narrative in my work,” she says. “Although this isn’t apparent in all the pieces, there are often moments where I make direct references to a place or name that firmly locates me in the work. In particular, the pink metal shutter Previous Owner has my mum’s maiden name cut out of the top, and then there are photos of me in one of her old dresses, barely visible behind the letters. I wanted the work to reflect a layered identity and personal lineage of names, both inherited and lost.”

She goes on to add, “I think it’s impossible for me to make work that isn’t political, even if there isn’t a literal connection. Often when I’m in the studio there’s a degree to which I switch off and allow a more subconscious process to occur in the making, but then I feel it’s important to give this context and consider the content with a more direct reference in the title.”

This combining of the personal with the alien is what keeps the viewer engaged. The unknown has never found a hospitable milieu on earth. Popular culture is rife with alien visitations and conspiracy theories that speak of transgressive takeovers as opposed to progressive skill transfers. The trope of visitation often presumes an entity not of this world, which encroaches and even disrupts what might count as life, but it is not just a fictional idea, it is often the state of human life as we know it. This fear of change is exactly how I understand Ackroyd’s Mulch. To acknowledge the alien is to also recognize the alternative, which not only includes the body, but also the planetary, biological and the political. Yet this show is no quick fix, no flashing signs of enlightenment will appear. This is a waiting game, a place for contemplation rather than action.