You currently have a show on at the Freud Museum in London. Can you tell me a little about it?

It all started following a visit to the museum almost two years ago. I visit Freud’s former home once or twice a year: I’m a groupie, I love this place, it’s local and I like to think that every visit I take something with me. This time in particular I thought about Freud’s narrow escape from Vienna in 1938, the way he was eventually allowed to leave with some family members, his belongings, cherished collections, books and even the famous couch. I thought of the parallels with my own family’s history and parallels with today’s refugee crisis.

“Memories are not erased, they are covered by another layer which makes them seem to disappear, but they don’t, they are still very much there”

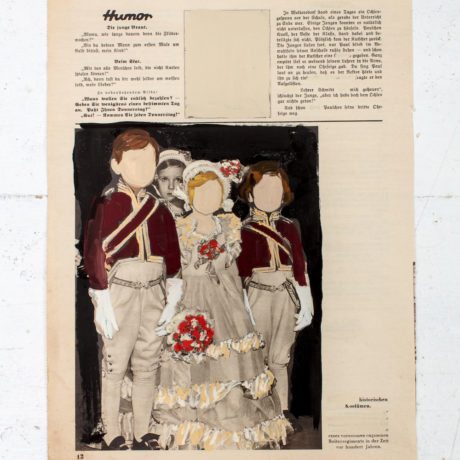

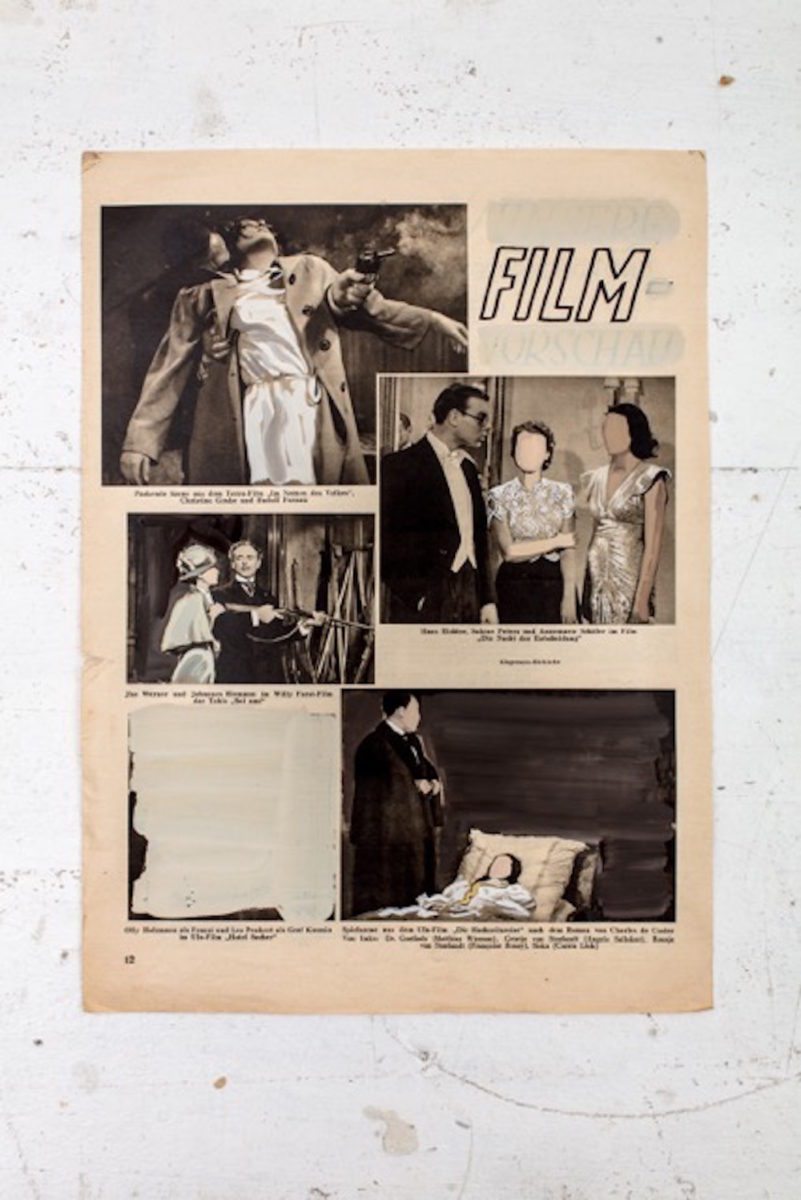

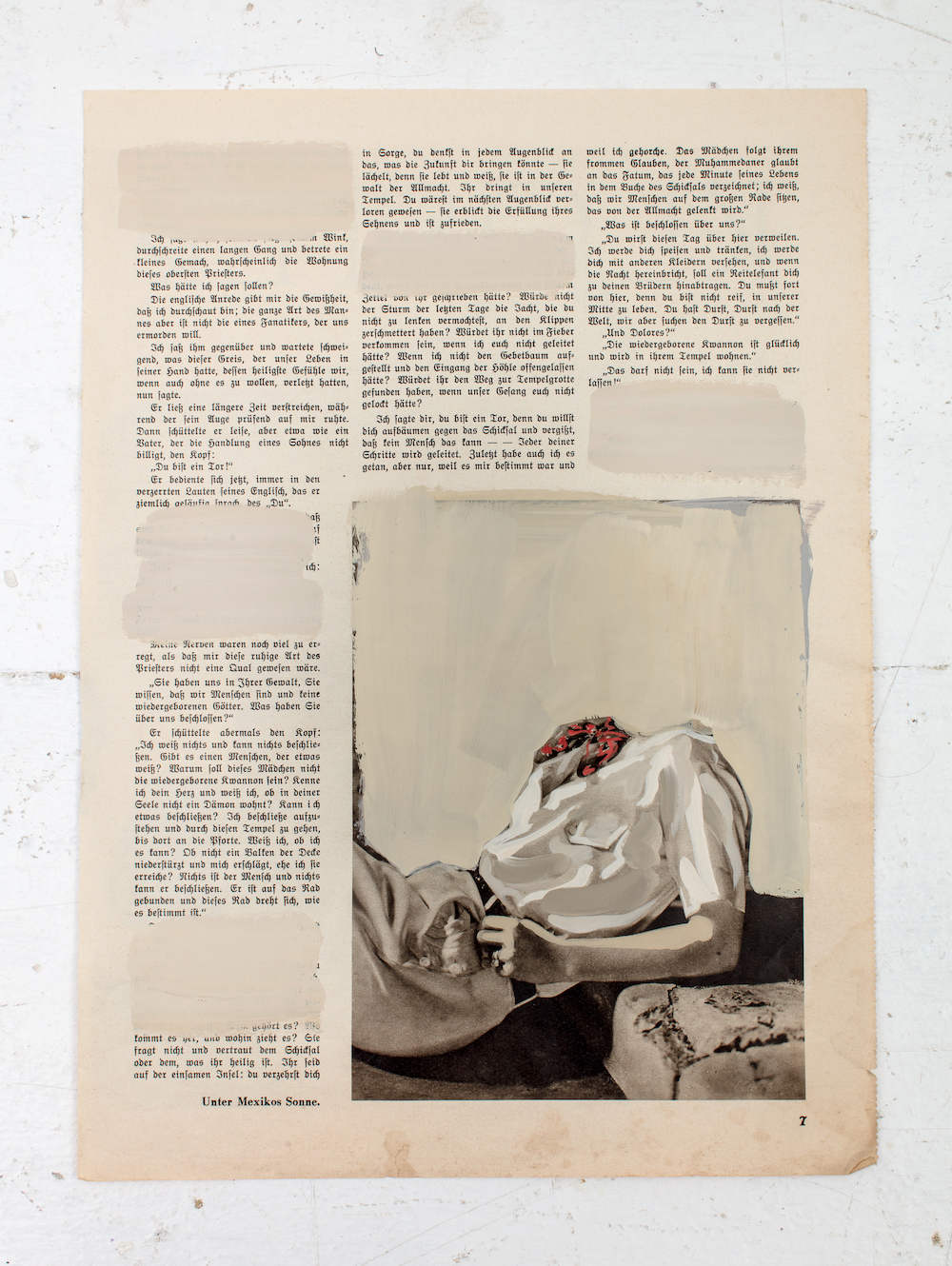

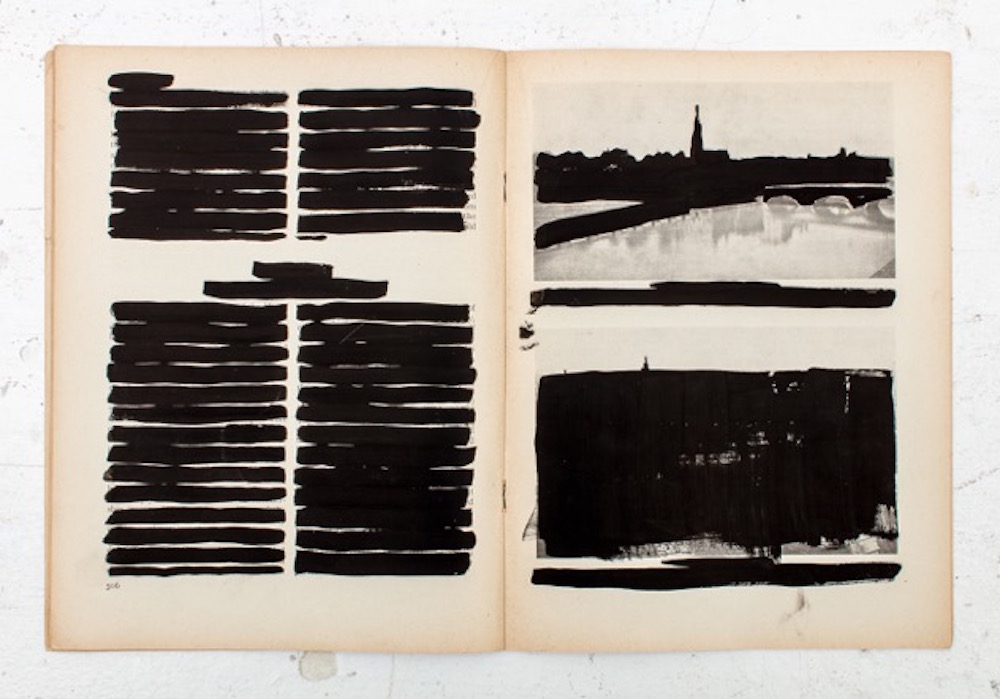

I have been working with 1950s and 1960s magazines and newspapers for the last couple of years. It began on an Outset residency in Tel Aviv where I worked with Israeli 1950s gossip magazines. Then I worked with 1960s pre-Cultural Revolution magazines on a residency in China a couple of months later. As I left the Freud Museum I found myself wondering about the magazines and newspapers which predated the war, the ones Freud and other refugees like him must have seen as they were fleeing their homes. What did these papers look like? Eventually I managed to put my hands on a few and immediately started painting over them, instinctively drawn to and also repulsed by the source material. Only when I was cutting out or painting over the swastikas and images of the Nazi army marching in the streets did it start to make sense. It made me feel better. In an era of fake news, it felt as if I was editing the news of the past. Editing history.

So I guess in Black Book I finally managed to combine a few of my obsessions: history, collective memories and those pre-sixties magazines, where all was more simply laid out; ideologies, right and wrong, work, family, even World War Two.

What was the process of sourcing and picking this imagery like?

Initially I asked the gallery I work with in Germany, Galerie Karsten Greve, if they could help me find these magazines. I had no idea where to even start looking for these publications, and I was unaware that they could not be bought or sold in Germany. My wife, Silia, jumped in and two weeks later I received a package with quite a few publications which she had found on eBay. Handling it felt very strange and eerie at first, but I got used to it.

“I’m not sure how I feel about nostalgia, but I’ve been obsessed with the notion of time since I can remember”

How do you feel the exhibition’s location in Sigmund Freud’s last home will influence the way the work is read?

I wanted to place my work amidst Freud’s personal objects and memorabilia unobtrusively. I wish for the viewer to hardly notice the little changes I made by inserting my works around the house. Also, my aim is not to focus solely on the Holocaust, attempting perhaps to bring one’s attention closer to our time, to the present. There is also the notion of erasing or painting over the source material, much like our memories, in keeping with Freud’s legacy. Memories are not erased, they are covered by another layer which makes them seem to disappear, but they don’t, they are still very much there. One of the interesting facts I learned about Freud’s collections when I was preparing the show was that the quality or rarity of the antiques was not crucial for him. Significant was the fact that they were actually unearthed. In some way I was trying to play with this process, turn it on its head a bit. There is also the challenging juxtaposition between the horrific nature of the work and its display in the intimate surroundings of the house.

You largely paint faceless figures, further evoking partial or fragmented memories. Where did this fascination with nostalgia and memory begin?

I’m not sure how I feel about nostalgia, but I’ve been obsessed with the notion of time since I can remember. Even in high school, the only class I found mildly interesting, challenging and thought-provoking was history class. One of my favourite past-times is roaming endlessly through antique markets and thrift shops. My parents’ house where I grew up is not that different from Freud’s home, filled to the ceiling with books, art and antiques. At the same time I can’t bare looking at my own past, my own family’s photo albums. I actually can’t stand it.

Many of your previous painted works have been deliberately ambiguous. How did making Black Book, where you’re dealing quite directly with a very specific kind of propaganda, differ?

I could not have imagined working with this explosive material. I have never before produced overtly specific political work. It always felt like going around the issues rather than facing them directly. Making the Black Book series felt like diving into the heart of some of those issues I have been and still am preoccupied with in my personal life, my family history and my work. It was touching where it hurt the most. I don’t think I would have been able to deal with this had the project not developed organically, as it did: from the way my wife accidentally bought Mein Kampf’s English translation assuming it was more of the same German magazines; and then I just had to react to what I found in front of me.

At the opening someone mentioned that the work felt like sticking your tongue out, a childish reaction. In a way I agree, how can one face this darkest chapter in human history? One of the books that changed the way I thought of evil and of the Holocaust was Alone in Berlin by Hans Fallada. It also reminds me of an article by one of my favourite Israeli journalists in Haaretz (a liberal paper, the equivalent of the Guardian) where, speaking of the current political situation in Israel, he writes that we should not expect, think or dream of winning. All we can strive for is protest itself, making our voice heard. That’s as noble as we can get.

All images: Untitled, 2017. Courtesy the artist