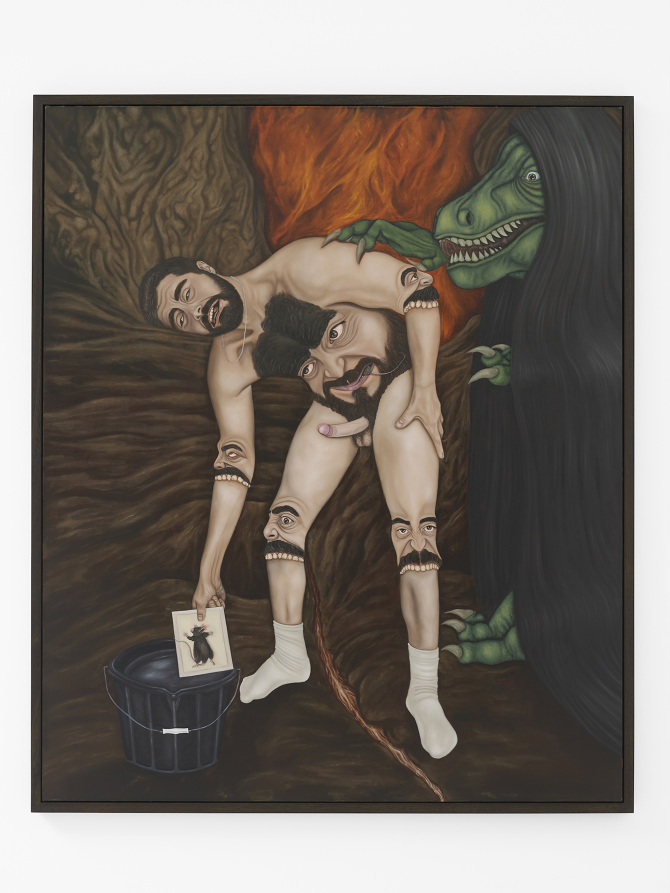

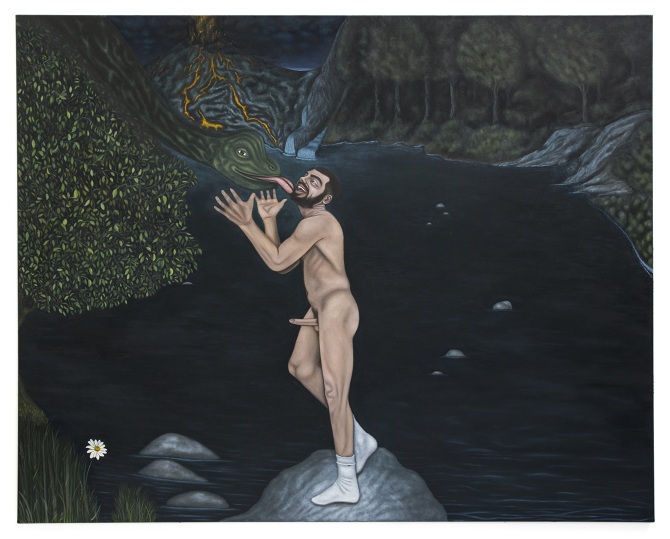

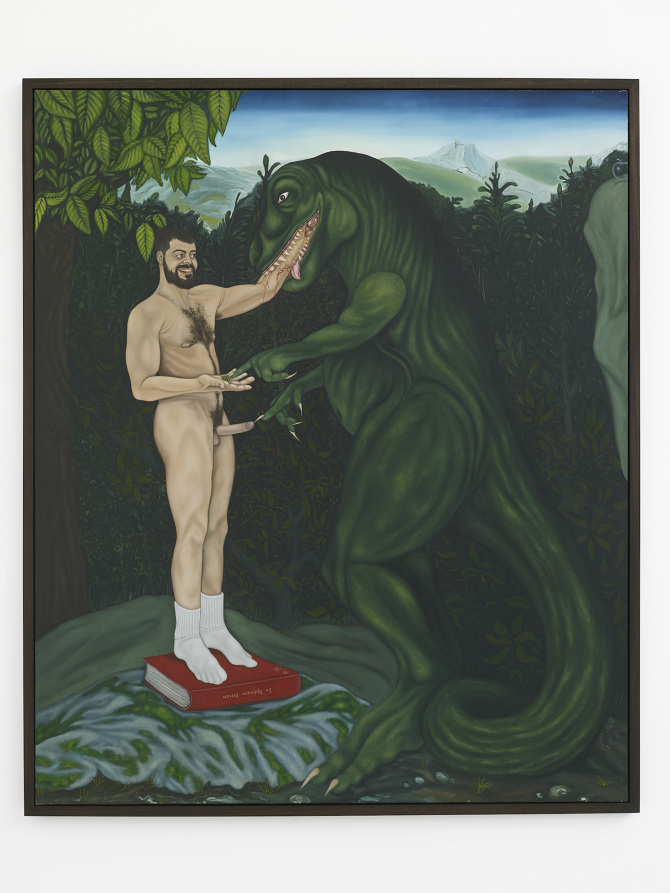

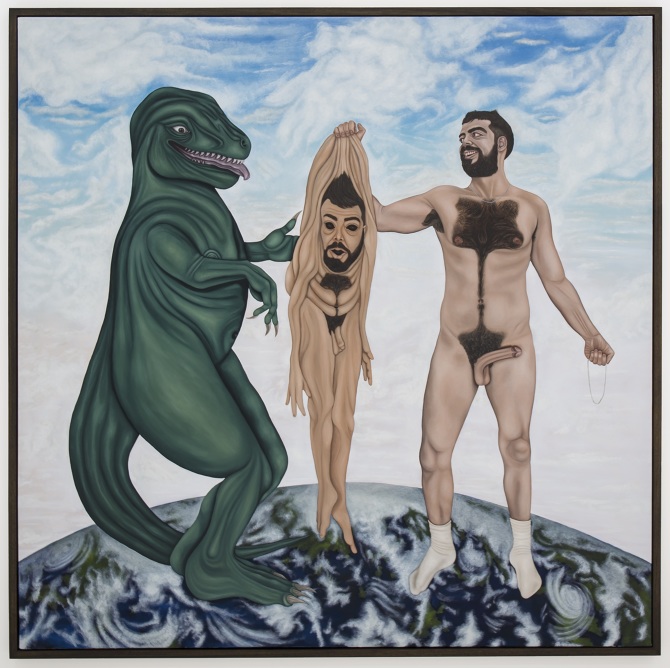

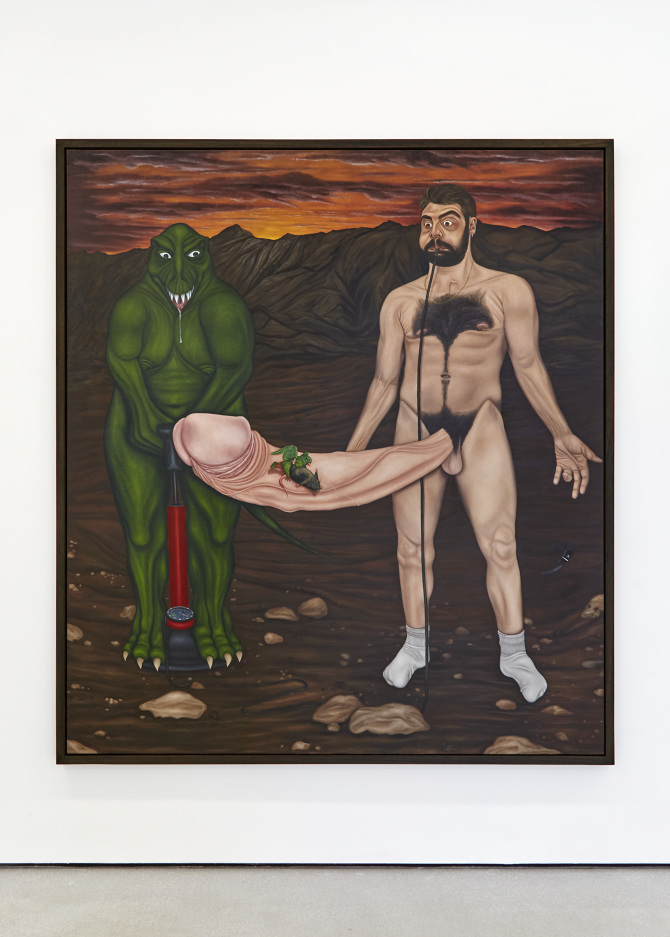

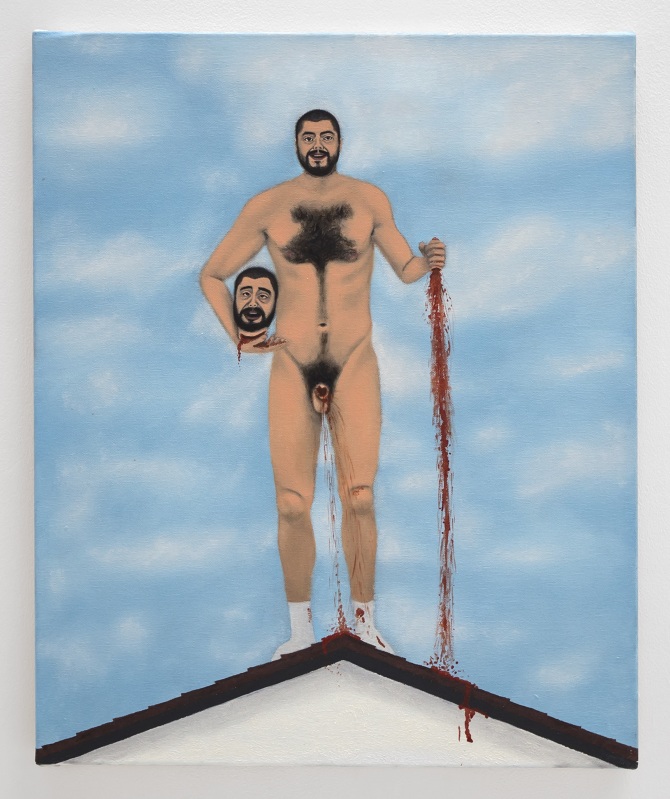

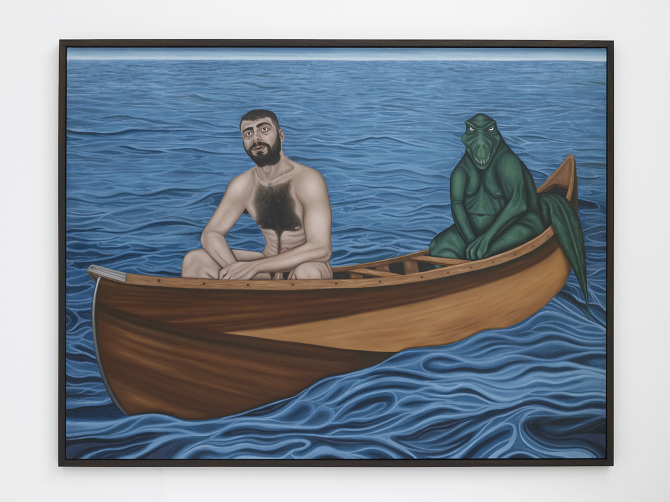

Strange, surreal and darkly humorous, Glen Pudvine’s paintings are nothing if not distinctive. The RA Schools graduate (he completed his MFA just this year) explores variations on a tight theme, namely the interrogation of his own image—complete with hairy chest and white socks. The central male character of Pudvine’s paintings finds himself in a seemingly masochistic relationship with a mysterious dinosaur, who obsessively haunts him.

Pudvine is influenced by everyone from Lucas Cranach to Hieronymus Bosch and Frida Kahlo, transplanting some of the horror and heavy symbolism of their work into a firmly contemporary interrogation of what it means to live as a man today. His protagonist grapples with his own sexuality, his engorged penis expanding at times to absurd proportions. Death and the failure of male virility bubble and seethe just beneath the surface. It is nihilistic provocation; it is heaven and hell; it is those damn white socks.

From Albrecht Dürer to Frida Kahlo, self-portraiture has a rich tradition. What does it mean to you to repeatedly represent yourself in your paintings?

Most of my decisions start off as a pretty simple idea. Perhaps funny or practical. The self-portrait originally felt like a way of exposing my total “normal-ness” or what I thought of as “normal”. I didn’t have anything to bring to the table. So I wanted to really wear that, and talk about silly inadequacies or things that would pop up day-to-day. The size of my feet, the TV I’d watch or the food that I’d eat. It then became an anchor, or something that would create perimeters, in my practice. I’ve always hated the stifling blocked feeling in the studio. The fact you can do ANYTHING!?—I actually find that quite suffocating. It felt fruitful and really invigorating to work like this. Through the narrowing of the avenue it opened up more doors, and I discovered what I’m actually interested in.

“The self-portrait originally felt like a way of exposing my total ‘normal-ness’. I didn’t have anything to bring to the table”

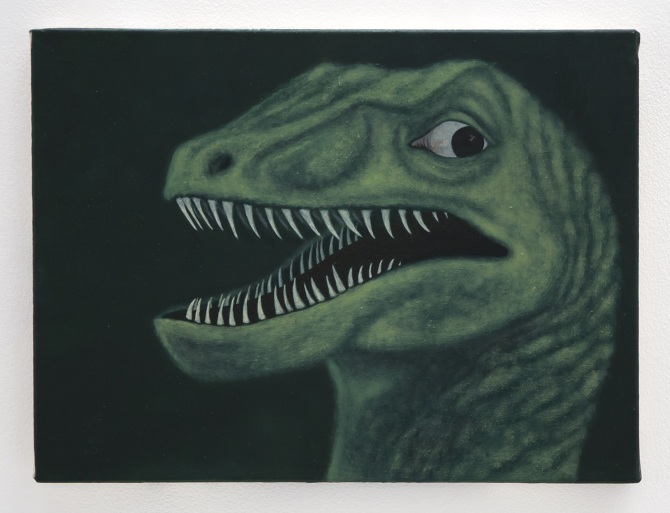

Your work at the RA Schools show was haunted by a Tyrannosaurus Rex—who is this mysterious dinosaur?

I’m not sure if its a T-Rex!? I started using the dinosaur as another self-portrait. The dinosaur always has my eye and a belly button and other human features. It was a way of including another character in my work that I thought I could use and that the “me” character could interact with. Dinosaurs aren’t here anymore, which is why I could use them but also made them a good allegory for death. And the self-portrait a good one for life. To be honest, I think all art is about death. If you want to make something that will be somewhere where you are not, or something that might last longer than you, then I think it is inevitably about that oblivion. I just think I’m particularly focused on or scared of it!

What are the best and worst reactions you’ve had to your work?

The worst reaction I’ve had is probably the best. It was about two works that I had in my Premiums show at the Royal Academy Schools, West Highland Terrier, and Going Nowhere. Someone called up to say that art had been their friend all of their life and that my work was the death of art. There was no feeling of love coming away from the canvas at all. “What’s next—a paedophile killing a baby!?” I would never paint that! I think.

Art history-wise, who are your main reference points?

I go to The National Gallery a lot. I like the Cranachs, Hans Holbeins’s The Ambassadors of course. I like everything there to be honest. I look a lot at Bosch. The experience of going to see works from Giotto or Caravaggio in churches is as much of a reference point too. The atmosphere of those places of worship is incredible and enhances the gravitas of the message. Post First World War German artists are also of influence. The artists from the New Objectivity movement. Christian Schad in particular got me interested in portraiture. The strange eerie lighting of his work has a cruel sharpness. I love Frida Kahlo and her sort of heavy-handed symbolism. It smacks you in the face and holds you for ages.

I also look a lot at Paleoart. Paleoart is a genre of art that emerged in the Victorian era which depicts prehistoric times. They are great artworks and are also wonderfully wrong to what we know now. I think this has a real affinity to the Medieval and pre-Renaissance work I look at. What we know now is not what we knew then, and is not what we are going to know in the future.

- What happens when a man goes through his own portal? 2019

- Born, 2019

“To be honest, I think all art is about death. I just think I’m particularly focused on or scared of it!”

There seems to be a mix of sexuality and horror in your paintings. Is there a relationship between these two things?

I suppose, in this context, the sexuality is part of life and the horror is part of death. I’ve been trying to deal with my immortality by thinking of death as much as a part of life as living. These seemingly opposite things are part of one whole thing so they actually need each other. It’s hard to see which is the sexy and which is the horrific because it is blurred through this coping mechanism. I think the erection in the works encapsulate this.

The erection could be a sign of my virility in the face of inevitable extinction. But the image is such an embarrassing cliche that it undercuts itself. The failure (death) of this type of “manliness” (life) I hope makes the viewer question what is behind the provocation. Furthermore, the erect penis is more full of blood than its flaccid alter-ego. Blood is often a sign of danger and then death, which makes me think of the precariousness of life and how fragile we all are in this universe. In my installation at the Royal Academy, the boner is then whittled down to a literal pointer. Its directing you to the next painting or message. Until you get to the last work, which is the dying scene or the “end”, and it points back the other way. To go back through time and start again. It seems quite nihilistic… but in a positive way I think. We’re so insignificant! It’s scary. I like that feeling.