When Aya Haidar was ten years old, someone asked her what her mum did for a living. She remembers replying, “Oh, my mum doesn’t do anything, she’s just a mum.” Her dad, who rarely raised his voice, told her he didn’t want to hear her saying that ever again and began listing everything his wife did: taking care of Haidar when she was sick; making sure she was dressed in clean clothes; cooking dinner for her when she came home from school. “He always said, ‘I might be paid for my job, but money isn’t the only thing of value’,” says Haidar. “That, and ‘Your mum’s job is harder work’.”

I’m talking to the Lebanese-British interdisciplinary artist over Zoom ahead of this year’s Abu Dhabi Art, where she’s showing two existing series of work and a new installation. After a foundation course at Chelsea College of Art, Haidar studied at the Slade and went on to do a masters in NGOs and Development at LSE (her work has always been socially and politically engaged, and she wanted to back that up with some theory).

For seven years she ran a charity that worked with refugees in Lebanon. Now a mother of four, she divides her time between her artistic practice and her children. We’re joined by her son Jad, who’s just a month old.

“I used to be a bit apologetic about having children,” says Haidar, as she breastfeeds. “Now I feel the need to talk about motherhood and the struggles and weaknesses we all share and feel but don’t discuss openly.” During a residency at Cubitt in London, she produced Out of Service (2019), a series of embroidered textiles that upend traditional notions of the domestic.

One work, Hi-Vis, comprises breast pads on a neon-yellow wall, their milk stains embellished with colourful stitching. “They’re just invisible bits of fabric that you slip into your bra to mop up your milk,” says Haidar. “I like to take this kind of stuff, which is physically hidden, and put it out there.”

“I used to be apologetic about having children. Now I feel the need to talk about motherhood and the struggles and weaknesses”

As the UK entered lockdown and the conversation around the division of labour within the home rose in volume, Haidar focused more intently on documenting the invisibility of women’s labour. Highly Strung (2020) began as a written record of small things that, if she hadn’t taken care of them, would never have been done. “There’s the physical stuff like ironing, cleaning, cooking, and the mental load of remembering to renew the library books, pack the swimming trunks, take the water bottle out of the fridge.”

Every night when her family was asleep, she sat up embroidering old socks, muslins and T-shirts, highlighting one act of labour a day. “It became quite ritualistic,” she says. “Though embroidering itself was another labour.” The 395 items were hung on a washing line and the complete set was priced based on working 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for a year, at the minimum wage.

“All my work is an extension of storytelling. It’s about creating an arena for discussion and reflection”

Haidar’s affinity with craft began with her grandmother, who lived down the road when she was a child. “I’m originally Lebanese and from a young age I’d sit with her, and she’d talk to me about her upbringing and my culture, customs and language,” she says. “As we chatted, she would always be knitting or sewing, and I’d do it with her. It wasn’t just a skill that I was trying to learn, like playing an instrument: it was part of the conversation.”

It was also her grandmother who passed on to Haidar an inability to throw things away: bedsheets would become clothes, then headscarves, then cleaning cloths. Haidar’s mixed-media artworks incorporate found and disposable objects that add extra layers of human connection. “For me, they’re such an important part of the work because they house stories well before I’ve even touched them,” she says. “They’re remnants of people and their experiences.”

“Found objects house stories well before I’ve even touched them. They’re remnants of people and their experiences”

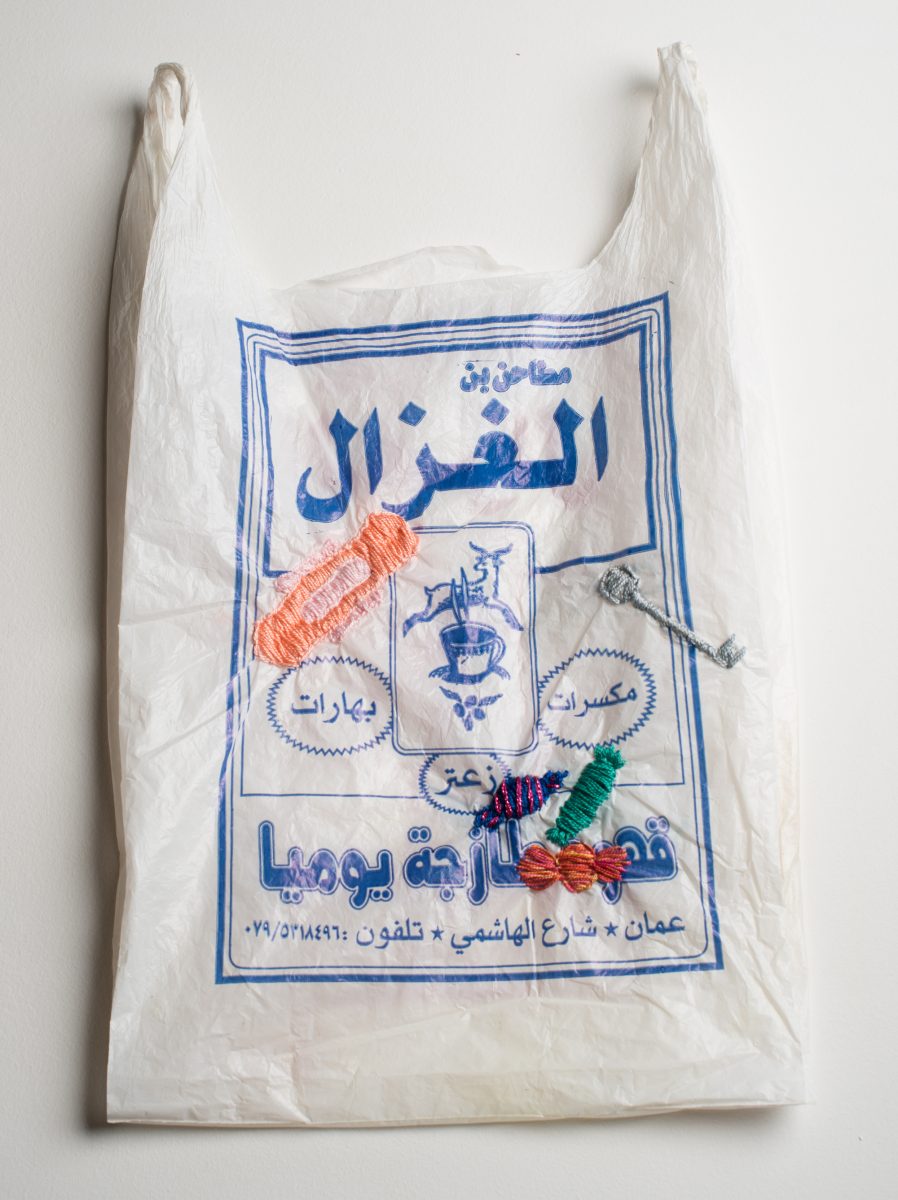

Soleless (2018) grew out of a three-month residency programme that Haidar did with Deveron Arts in Huntly, Aberdeenshire, that aimed to integrate Syrian refugees into rural Scotland. In response to conversations with the newly arrived men, women and children, she embroidered intimate images of migrant families’ journeys onto the worn-out soles of the shoes that had carried them across borders. When they fled, they brought with them essentials in plastic bags.

In Kiass (2018), Haidar embroidered the objects, which range from cigarettes to sanitary pads, onto the bag of the respective owner. One woman brought with her a falafel maker because she didn’t know where she would end up and she had to feed her kids. Her own parents fled the war in Lebanon during the 1980s, so shining a light on displacement and forced migration has always been significant to Haidar. That, and the role of women.

For this year’s Abu Dhabi Art, she was commissioned to make a large-scale public work that explored Emirati heritage, and she responded with Dwelling on the Past (2021), which seeks to demystify the active part Bedouin women played in the preservation of their tribes. Inside a reproduction of a traditional black-and-white tent made from plastic thread (a nod to the negative influence the petroleum industry has had on these communities) are three garments that reflect women’s skills as communicators, traders and shelter creators.

“All my work is an extension of storytelling,” says Haidar. “It’s triggered by a conversation or an experience, and it’s about creating an arena for discussion and reflection. It’s about planting a seed.” As her day-to-day existence feeds into her practice, her work continues to evolve, but running through it all is her desire to share silenced narratives and make the invisible visible. “I firmly believe that art has the power to create social change. It can transcend language, it touches on people’s emotions.”

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, will be published by Trapeze in April 2022