Huguette Caland is a Middle Eastern woman. She was born in colonial Lebanon and her father became the first post-independence president of the country. What do you expect her art to be about? The influx of news that a Western audience hears about the Middle East has given us stereotyped ideas around its politics and society. We hear about “political unrest”, about war, fights for freedoms and lacks thereof. Artists of the region bear the weight of this expectation and have to fight harder to be seen as individuals with the creative freedom to focus on what they want.

There are particularly harmful stereotypes around Middle Eastern women and sex. The mismatch in expectation and reality has been researched and discussed extensively by Shereen El Feki, author of Sex and the Citadel: Middle Eastern women want and enjoy sex as much as people anywhere. The link with the colonization of Middle Eastern countries has not gone unnoticed, and there’s research to suggest that some societies were more sexually open before the colonial era, and yet orientalist conceptions that make and police ‘the Middle East’ as a homogenous idea ignore this.

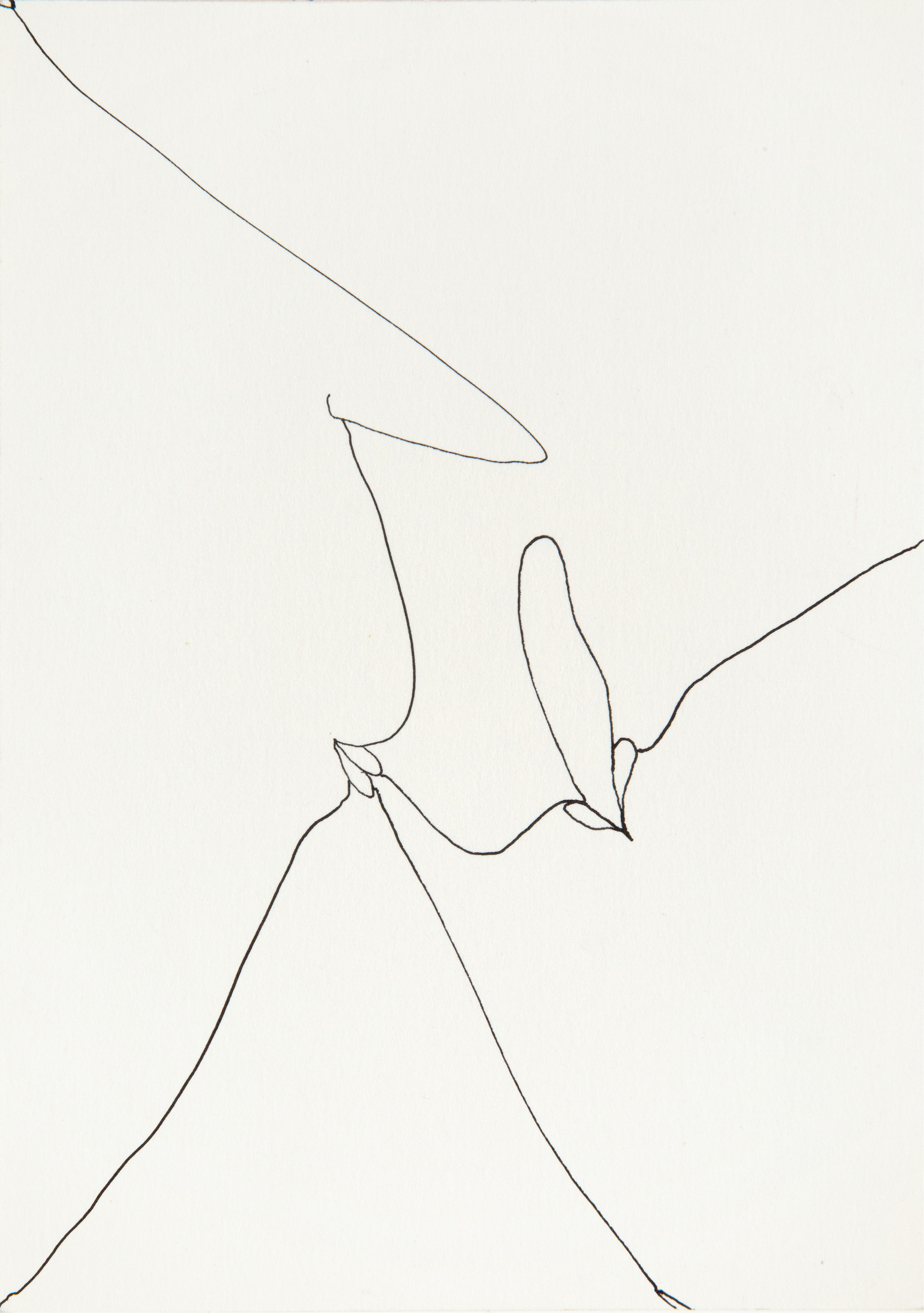

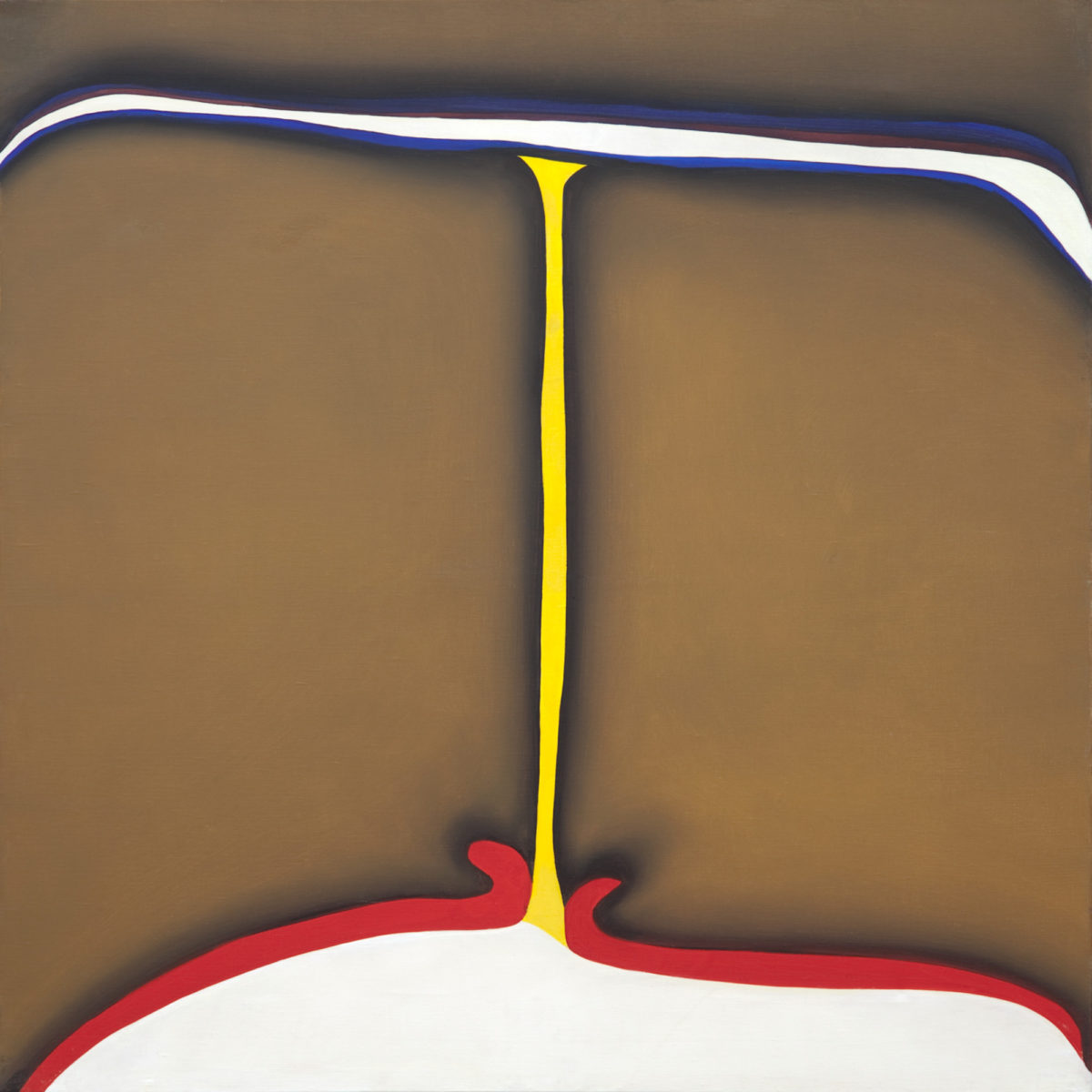

- Left: Monsieur Visage (Mr Face), 1980. Right: Bribes de Corps, 1973

Caland, whose first UK solo show is currently on display at Tate St Ives, defies those expectations. Middle Eastern women in particular bear a weight of how they do and ought to interact with sex—the assumption often being that they are sexually illiberal and repressed, and particularly if they are Muslim.

To admit to something of which I’m ashamed: I had internalized the view that Muslim majority communities had repressive and restrictive views towards sex, especially in relation to women. This is a stereotype possibly held by more than will admit it. I came to holding this view as I grew up in a conservative household with two (barely practising) Muslim parents.

Caland herself was from a Christian family, yet some stereotypes regarding illiberalism about sex and the Middle East are inextricably linked without regard for individual or community context. Her work is erotic, explicitly referencing her sexual and romantic relationships and personal life.

The Tate exhibition focuses on the period between her father dying (in 1964) to the end of her time in Paris (in 1973). As a viewer, the interpretation is of a woman freed of familial (which in this case also meant political) expectation. Caland as an artist—both in how she lived and what she created—reflects Lebanon’s own independence and the colonialist expectations and ideas placed on women in particular.

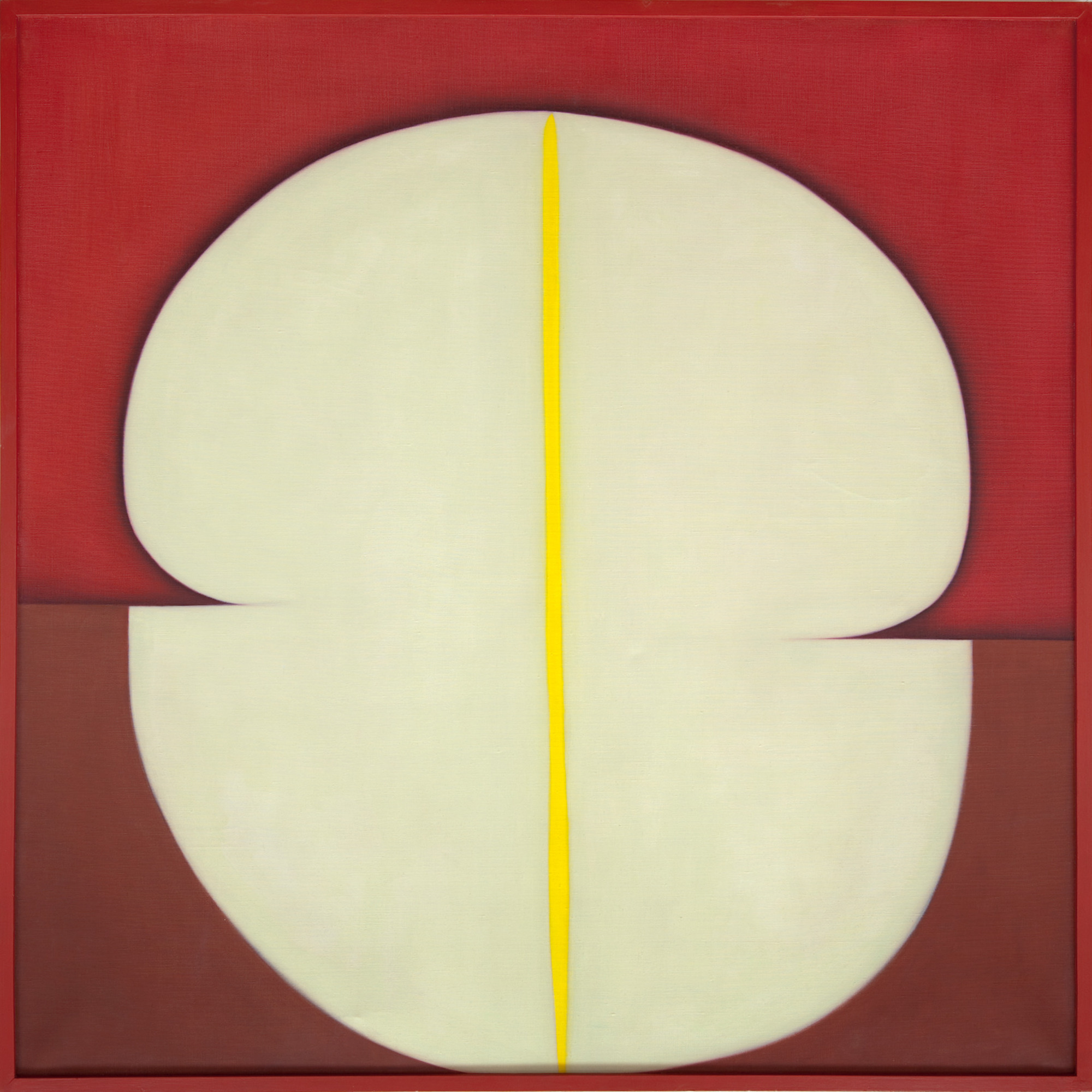

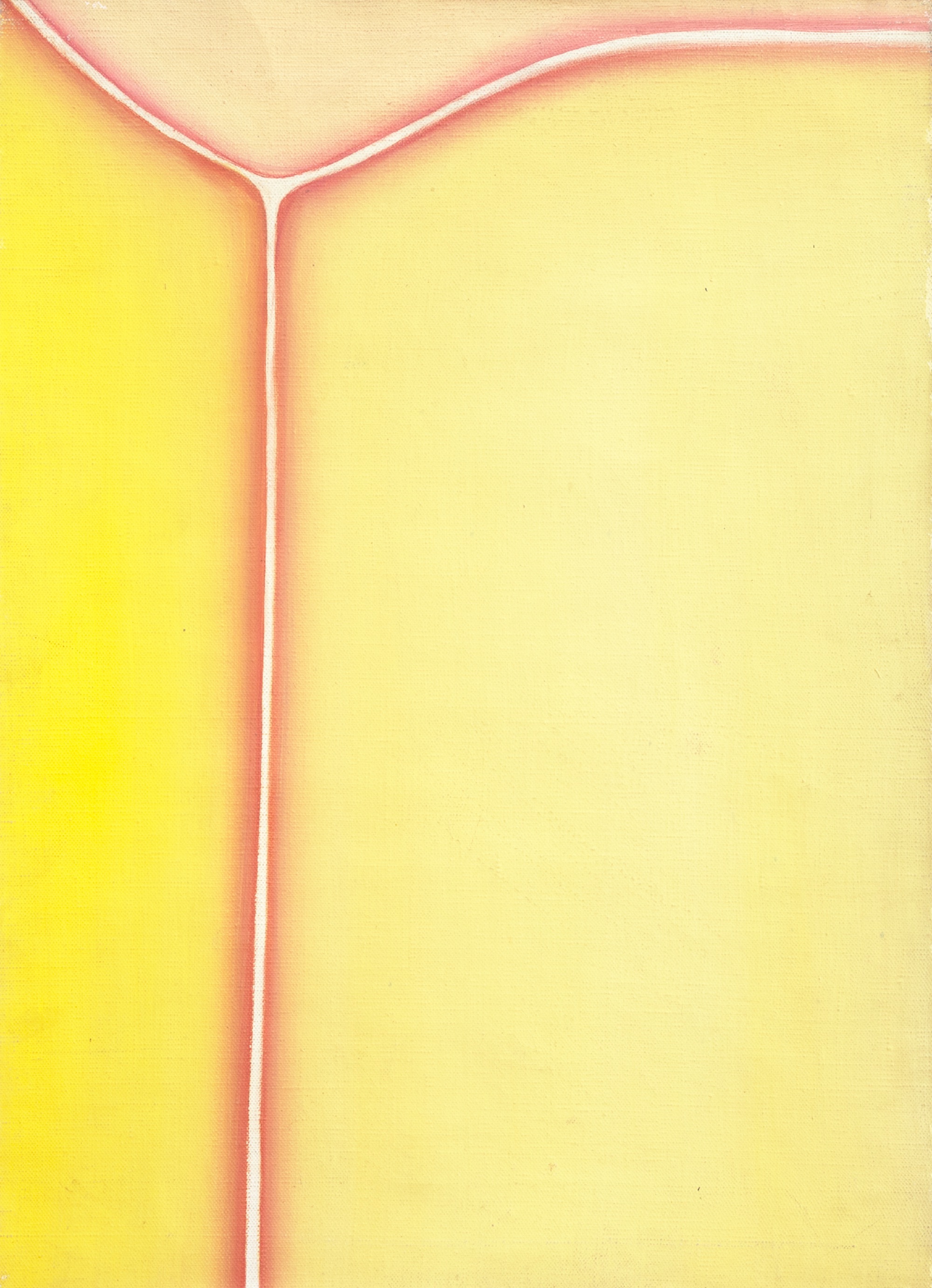

- Left: Family, 1978. Right: Kiss, 1968

It is only more recently, with further exploration into Middle Eastern and Islamic culture, that I have come to realize that much of the narrative around sexual repression and connection may be down to portrayals in the mainstream media and Western culture. Take, for example, the reportage of incidents of sexual assault in Cologne on New Year’s Eve of 2015, implied to be migrant men from the Middle East and northern Africa behaving in violent ways towards women—in part due to their repressed attitudes to sex.

To go further, there is perhaps an expectation that art from the Middle East must be political and those works that we choose to display in UK galleries may reflect this curatorial attitude. For example, part of Manal Al Dowayan’s Suspended Together sits on display in the British Museum. The piece comments on women’s guardianship in Saudi Arabia, a politically charged topic, again proliferating the idea that women aren’t free—sexually or otherwise.

Yet, even after feeling enabled to pursue a life and career as an artist, Caland felt the weight of cultural expectation of her Lebanese environment, where everyone knew her as a former president’s daughter. This led to her to leave for Paris, leaving behind her husband, lover and children. Brigitte Caland, the artist’s daughter, explains the move as one where she was “liberated from the weight of her life.”

“This was her breathing, shedding what was expected—she was finally living as herself—as a woman, as a person.” The process had begun in Lebanon through a sartorial as well as an artistic action in her design of a kaftan—the cause of dispute between she and her husband—which signalled a choice to leave behind a more formal style of dress in favour of freedom. The decision raised eyebrows and invited judgement, but can be explained simply: in Brigitte’s words, her mother’s attitude was “this is my body and I want it to be free—I want to wear my clothes.”

Artistically too, she chose to focus on sex, defying expectations around women of the region that remain today. Her self-portraits within her Bribes de corps series are a celebratory relishing of being a woman without the Twiggy-like proportions considered beautiful at the time. The salutary ‘Hi!’ is a 1973 line drawing of herself, nude, splayed, without shame. My favourite is Baiser volé, another line drawing from two years previously, where she captures both intimacy in a way which is at once both suggestive and explicit.

Freeing oneself of expectation does not come without cost. For Caland, it meant moving away from loved ones. The separation was felt, and this can be seen in her work of the later 1970s. Her powerful, seductive work is an example of the fact that to be apolitical is not a privilege afforded to everyone. Ultimately she reveals that you can move physically, but some sufferings of home cannot be ignored.