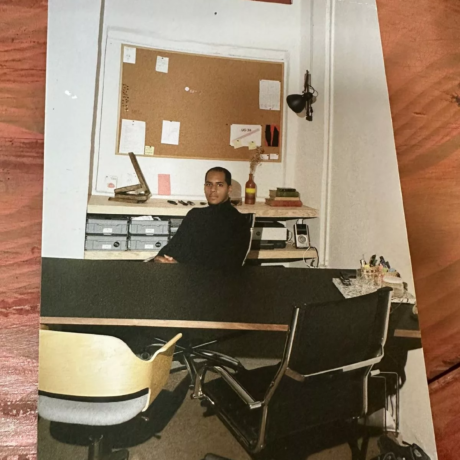

Under the Bad Taste moniker, Monroe works across art direction and food styling, but is best known for her “colour meals”, meticulously crafted monochromatic dinners that pair food with installations, performances, sound, projections and more.

These events began life as small, at-home affairs with Monroe’s sister, inspired by the scene in Joris-Karl Huysmans’s 1884 novel À Rebours, in which the protagonist creates an all-black funeral feast in memory of his “deceased” virility. Her first formal ticketed event was a distinctly DIY affair in a makeshift kitchen attached to a yoga studio, with a dinner accompanying a screening of Yugoslavian avant-garde director Dušan Makavejev’s Sweet Movie.

It’s little surprise that Monroe majored in English literature; what’s more surprising is that she has no formal training in art or food. Instead, she’s worked in kitchens since she was young, and clearly boasts an intuitive sense of what’s not just beautiful, but strange and beguiling when it comes to the visual and experiential side of food. Today, Monroe balances commissioned client work with events addressing bigger issues around food—her current project is a dinner considering the effects of “colony collapse disorder” and the plummeting bee population.

“I would make the argument that all chefs are artists”

What do you ultimately see yourself as: A chef? An artist? An events producer?

I like to think of myself as a chef first and foremost. I would make the argument that all chefs are artists, and I think that all people who cook things are chefs. For me, there’s something a little redundant about a title like “chef plus artist”.

I see your point about cheffing’s inherent artistry, but where does the line blur? Surely cooking something that’s just functional isn’t art?

I want to believe that thinking about any medium as “art versus not art” is a way to create hurdles for people who might not have any formal training, especially in the art world. People who haven’t been to art school may be more hesitant to call themselves artists; but I believe that if you’re putting objects A and B together to make C, you have made art. It doesn’t really matter if it’s good or if it’s academic: if you made a thing where there wasn’t a thing before, then you have made art. I feel the same way about food. We can all afford to be a little bit looser about how we employ these terms, and lower the barriers of access. Anyone can be an artist, and I think anyone can be a chef as well.

What do you hope people get from your work and events?

I’m often hoping to elicit the experience of being in a dream, or at the very least, of stepping outside the city that you live in for a couple of hours and entering some kind of alternate reality for a little while.

“I feel as if the direction that we’ve taken in the past couple of years with regard to food and wellness has taken quite an insidious turn”

When I start thinking about a dinner, I always think about what I want the diner to feel like first, and the food happens after that is established. The food for me is a way of digging further into the feelings that I want to elicit. And of course, you want everything to taste good.

What’s refreshing about your work is that it takes food outside of its more problematic connotations—things like body image, obesity, the “wellness” trend—and puts it into a context where it becomes very playful and beautiful.

I absolutely do kind of want to separate myself from all of those more fraught schools of thinking. I feel as if the direction that we’ve taken in the past couple of years with regard to food and wellness has taken quite an insidious turn in terms of the way we think about class and access—what kinds of people consume what sorts of things, and how do we use food to talk about what kinds of people we are on social media? The flipside of that is that I have to recognize that I’m so, so privileged to be able to treat food as a medium and have access to it enough where I can just play with it. The goal is very much to try to think about it as escapism, and to divorce it as much as possible from thinking about things like “wellness”.

What do see for the future of food imagery, and how it’s disseminated?

Trends work on a pendulum. When you think about things like Twitter and the way that it’s enabled things like slang or memes, everything is increasingly short-lived. I think the way we treat food will be on a similar curve in terms of how we use easily digested imagery and certain kinds of food as cultural shorthand. I think that stuff will continue moving in these increasingly meaningless visual bites: that’s probably just going to keep going until it can’t get any more abbreviated—until we can’t continue to mine food for meaning in convenient ways.

This article originally featured in issue 39

BUY ISSUE 39