“Light,” says the New York-based artist Leo Villareal, “is a very seductive material, and as humans we’re very attracted to it.” Standing before Detector (2019), an eleven-metre-wide LED screen of constantly shifting pixels that cloaks an entire wall of London’s Pace Gallery, it is difficult to disagree. Specks of light glimmer in and out with an almost musical grace, though Villareal’s installation thrums in silence. While coded so that no single orientation appears twice, Detector tricks its viewer into seeking out patterns. Villareal combines seemingly mundane elements—light and code—to mesmerizing effect. The vast screen feels simultaneously microscopic and cosmic.

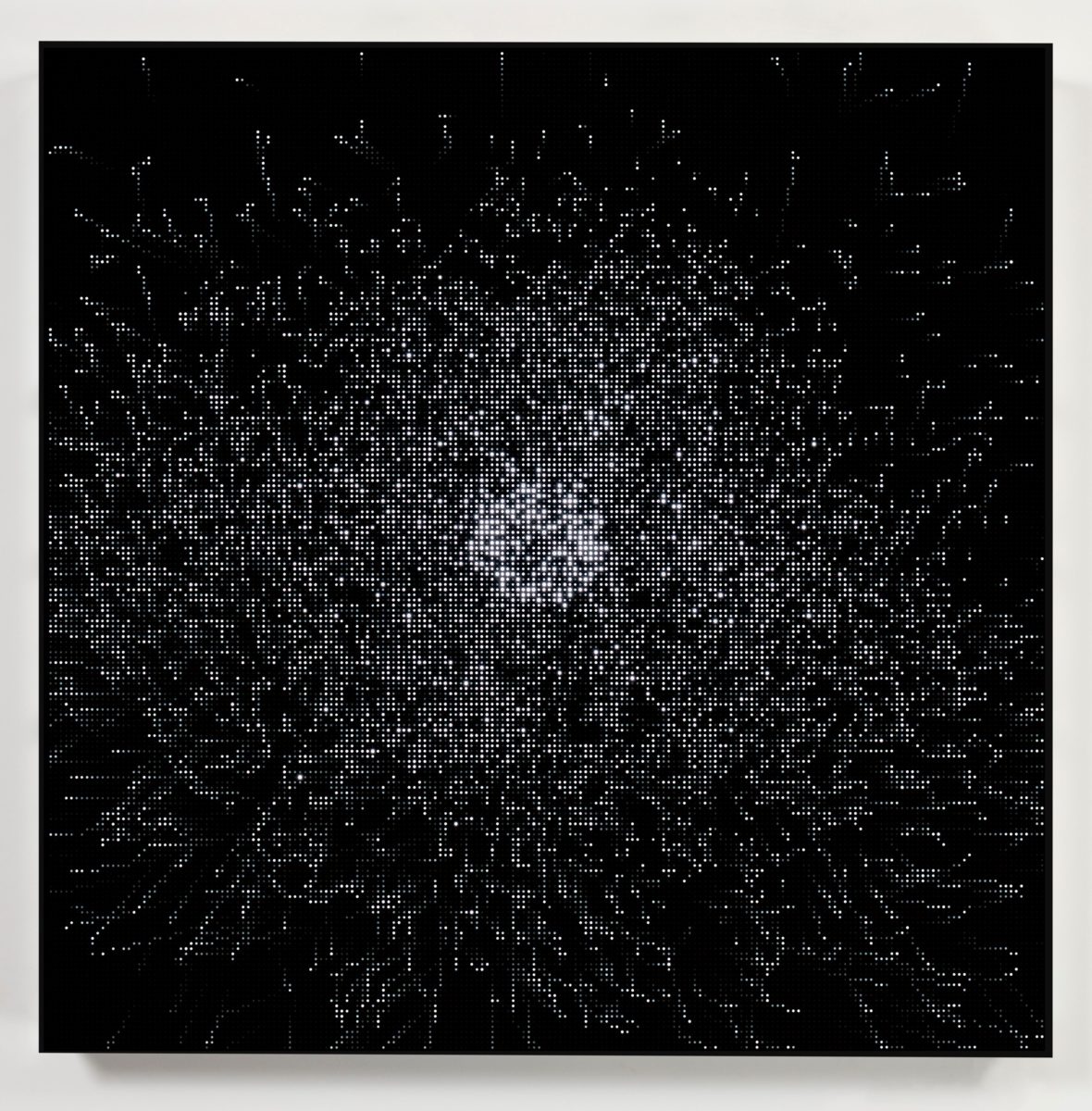

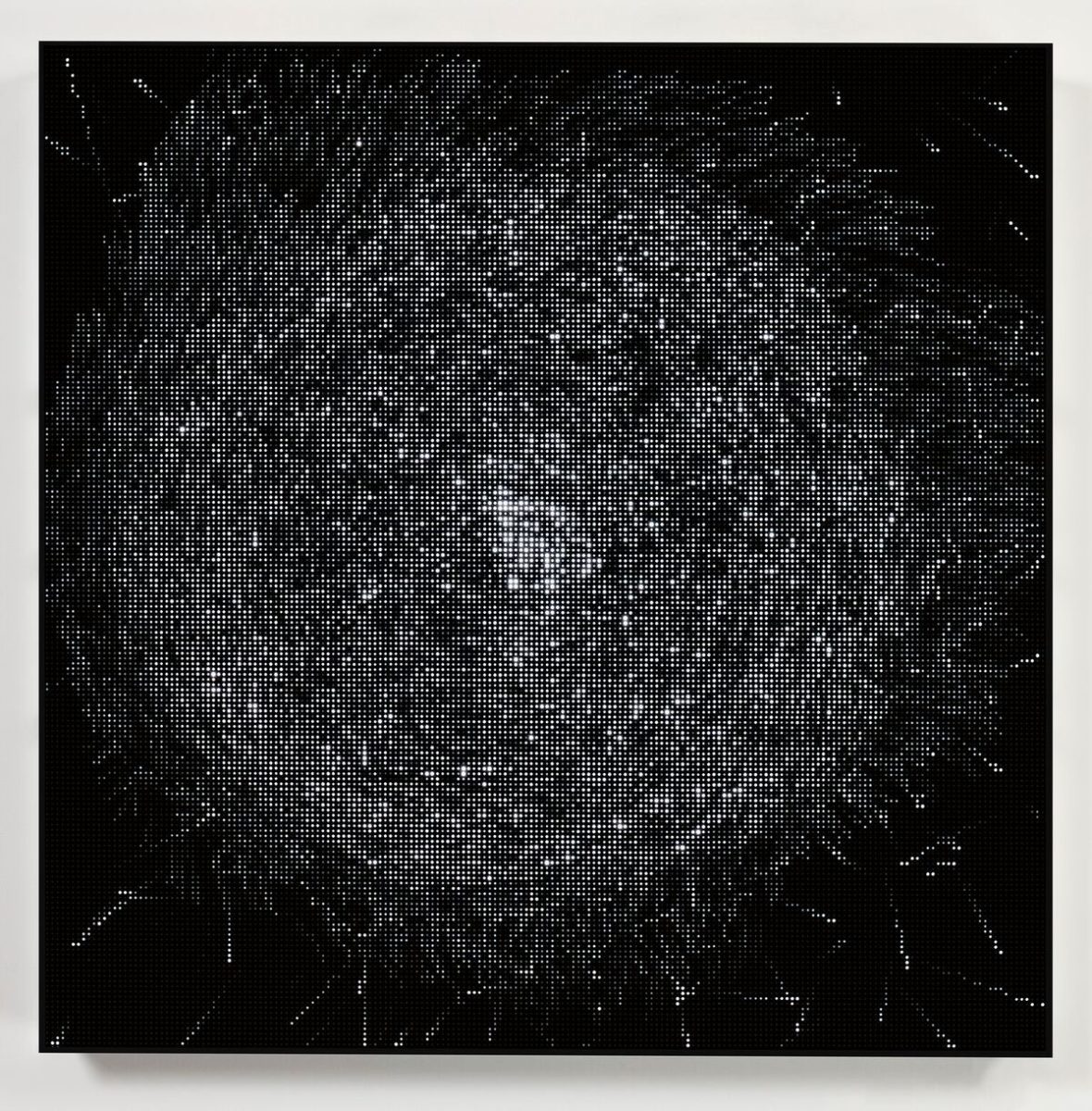

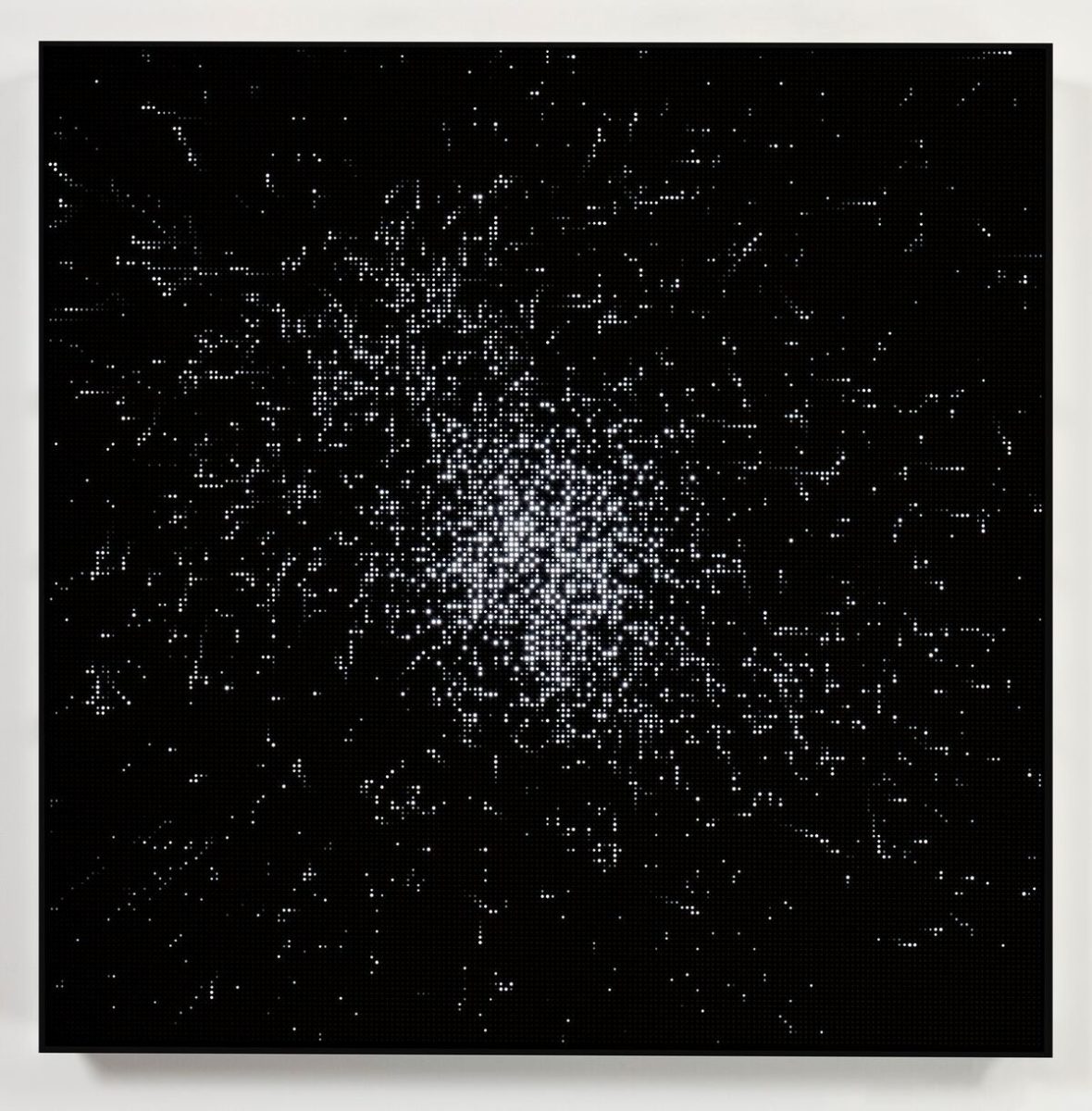

Villareal is at Pace to open his first solo exhibition in the space, though he has previously exhibited at the gallery’s New York and Hong Kong branches. The exhibition collects recent works from four different series. Each follows similar principles, but differs in size and form. Six pieces from the Instance series (all 2018), on one-metre-square LED screens, have a grainy, pixel-like quality, while the immensely larger, rectangular Optical Machine I and II (both 2019) contain more minute gradations of light, each differentiated in sequencing. “The first,” says Villareal, “is more centred, radial, and you see the geometry. The second is looser, more organic. It’s not quite as dense.”

“Light is a very seductive material, and as humans we’re very attracted to it”

Villareal’s journey to light art was not preordained. He studied sculpture as an undergraduate at Yale, and still sees himself as working in that tradition. “Even though these pieces are more like paintings,” he says, “I think the way that they activate the space around them is important.” After Yale, he completed a postgraduate degree in Interactive Telecommunications at NYU’s Tisch School of Arts.

Then, in 1997, inspiration came from an unexpected place. On one of his regular forays to Burning Man, the collectivist festival in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert, he realized that he could use his knowledge of coding to guide his way home each night. “My first experience of the festival was getting profoundly lost,” Villareal recounts. “So I took sixteen strobe lights and a micro-controller, and made a beacon for myself. I didn’t really think of it as an artwork—it was a kind of utilitarian device.”

At Pace, though Villareal’s lights move in an infinitesimally more elaborate arrangement, the basic principle remains the same. A simple set of rules—whether a light is one or off, waxing or waning—is deployed to create a complex, ever-shifting image. In this he was influenced by mathematics, particularly John Conway’s cellular automaton the Game of Life, where grids of cells move between states based on their interaction with each other.

In recent years, Villareal has been invited to create a series of increasingly immense public installations. Multiverse (2008) clad the connecting corridor of the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., in a curving arc of lights, while Hive (2012) crowns the roof of New York’s Bleeker Street metro station with a luminescent honeycomb of transforming colours. In 2013, he executed one of the largest-scale artworks ever realized: The Bay Lights, which clothed 2.9 kilometres of cables on San Francisco’s Bay Bridge in 25,000 LEDs. The illuminations proved so popular with a wider public that in 2016 they was reactivated permanently. “It was the first time that I really worked with a massive audience, tens of millions of people. And I wanted to create something that anyone could look at and have a response to, whatever they thought about art or technology,” he reflects.

Back in London, Villareal is partway through another humongous scheme. The Illuminated River will see fifteen of the Thames’ bridges bathed in LED lights each night. The artist’s scheme, planned in collaboration with the local architects Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands, was selected in late 2016 from a shortlist of six, whittled down from 105 entrants. Four crossings have been illuminated so far, with the final phase estimated to complete in 2022. It is estimated that it will be viewed 130 million times a year during its decade-long lifespan.

“A simple set of rules—whether a light is one or off, waxing or waning—is deployed to create a complex, ever-shifting image”

Villareal is matter-of-fact, even modest, when asked why his plan—initially titled Current—was chosen. “Our approach,” he explains, “was to think about the way the bridges had been illuminated historically. We talked to the architects were we could, and looked at precedents like the Olympics.” They found that many previous illuminations had been conceived hastily for short-term festivities, “not thinking about permanence.” The Illuminated River had to be a project that people would be happy to live with. “We wanted to do something that added something but didn’t take over.”

It has been a strenuous process. “I spent night after night down on the bank of the Thames working live, tuning and adjusting, making very subtle adjustments,” Villareal recounts. “When I was working in June, I would start working at 10pm and keep working at 4am.” Unexpected challenges abounded. “We had crazy things,” he continues. “One time, birds had made a nest in one of the lights, so we had to wait for the birds to hatch.”

The results, which are so far displayed on Millennium, Southwark, Cannon Street and London Bridges, are elegantly attuned to the pace of the city around them. The sleek concrete span of London Bridge has a prismatic sheen of colours along its side, while the interwar Southwark Bridge has a volumetric rainbow wash that continues through its cast-iron underbelly. The project’s palette, which adds a warming amber to the standard LED shades of red, green and blue, is partially inspired by the great Thames painters of the past, such as Turner, Monet and Whistler.

Though The Illuminated River was modelled using virtual reality programs, Villareal has resisted the present vogue for VR artworks. “I don’t like the isolated nature of it. I like to figure out how to do it more communally.” From his smallest panels to his most gargantuan public pieces, Villareal has a consistent desire create shared experiences among his viewers that contrasts with the solipsism of much art-world VR. He is, however, eager to implement other developments in technology. “There are new things,” he says, “happening in all sorts of places. Not only the light instrument themselves but also the controls, to control sound, light, images, slicing and dicing.” He is soon to move to a new, double-sized studio, still in New York, which will allow him further space for experimentation.

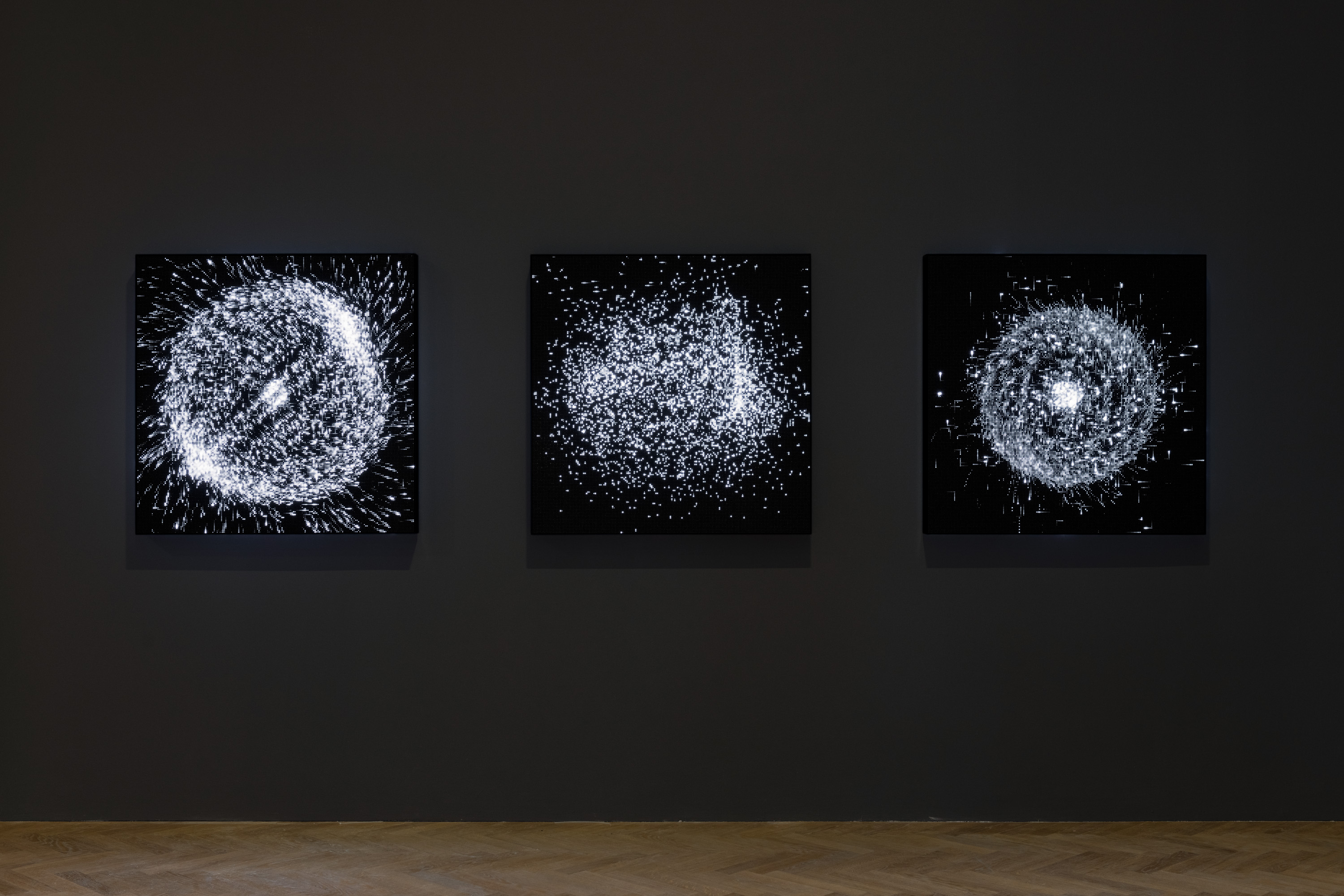

Away from the main hall of Pace, Villareal has installed one of his most technologically advanced pieces in the gallery’s office. Corona (2018) transports Villareal’s light sequences onto three organic light-emitting diode (OLED) screens, which can each display around 8 million pixels. Arranged in a triptych that evokes the religious altarpieces of the Renaissance, it takes the precepts of the works in his exhibition to a new plateau of intricacy, its lights darting with an extraordinary liquidity. “I think that there’s a danger with technology. It can take over. As an artist you have to be driven by ideas and keep the technology in check.” Gazing into Corona’s hypnotic harmonies, I am left in no doubt that its artist remains firmly in control.