Brighton is always screaming. It is set to a never-ending soundtrack of squawking gulls, squealing amusements and shrieking revellers, who descend in their droves in the pursuit of pleasure, whenever the sun shines. Salt too, dominates the air, whether it be the stench of greasy chip paper or the sea winds, which whip against Victorian ironwork and Regency facades, constantly clawing and corroding.

The city oscillates between perpetual party and sinister romanticism. The euphoric beats of Right Here, Right Now, Fatboy Slim’s clarion call to “live in the moment”, are the unmistakable anthem of blissful, hazy summer days satiated by beer pitchers and shots of Tuaca (the Italian liqueur that has long been favoured by residents, if only as a spicy alternative to the acrid sting of sambuca). But while many see Brighton as a place of glorious escape and even refuge, it has a darker side. Once the clouds descend and the tourist traps shutter, the streets become desolate, and the formerly vibrant promenades are tinged with barren menace.

Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock (1938) is famed for its portrayal of grisly murder and nefarious gangsters, but it is the vivid picture of the city’s more squalid parts that truly resonate. He articulates a vague sense of unease, which still hangs around Kemptown’s shadier corners and the neglected archways of Madeira Drive. Likewise, biographical drama-documentary 20,000 Days on Earth (2014) reveals the emotional imprint that Brighton has made upon on the Australian musician Nick Cave since he took up residence. “It is forcing its way violently into my songs,” he says.

“He is lit by the blinking illuminations of the Palace Pier, a glorified amusement arcade that stands in the shallows like a gaudy Christmas bauble”

In the film’s final scene, he steps out into the night, across the pebbled beach and towards the black void of water beyond. For a moment, he is lit by the blinking illuminations of the Palace Pier, a glorified amusement arcade that stands in the shallows like a gaudy Christmas bauble. As teenagers we hung out here, ignoring the rickety rollercoaster in favour of playing penny pushers, before braving the elements on deck. We would huddle together, looking out to sea, while clutching bags of freshly fried doughnuts—five for a pound. The sickly-sweet smell is more evocative than any battered fish or hard candy could ever be.

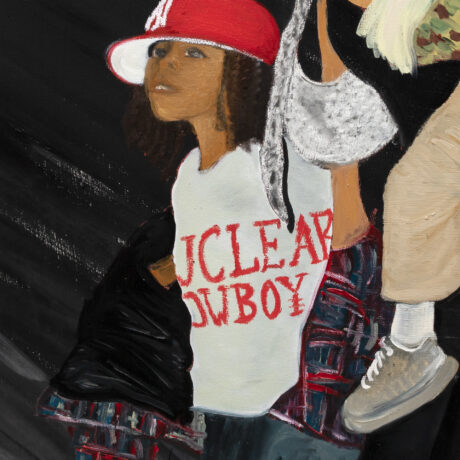

The photographer Ian Sanderson was in the same spot some years before, corralling another gang together to take in the view—my mum and dad included. He snapped them leaning against the pier’s florid railings and modelling the latest wares from Chevignon, at the behest of a local fashion boutique. Despite the promotional intent, there are no affected grins or rays of blazing sunshine here. Just a group of friends, windswept and laughing, standing against an ominous grey sky.

In memory of Ian Sanderson (1951–2020) who shaped the way I see the city

Holly Black is the managing editor of Elephant