The ocean and the climate are inextricably linked. For millions of years, the seas that cover nearly three-quarters of our planet have functioned as heat and carbon sinks, regulating conditions on earth. The flora and fauna of the ocean, much of which we still know little about, is crucial for maintaining a delicate equilibrium that sustains life on this planet. And yet, in just the last two centuries, human activity has lead to a 30% rise in acidity in the oceans and temperatures have increased by more than one degree Celsius, threatening not only to destroy marine habitats but to irrevocably alter life on earth.

Two artists who explore these delicate processes and ecosystems are currently showing new work at the Villa Carmignac, an art foundation on the French Mediterranean island of Porquerolles. Presented as part of the group show La Mer Imaginaire (The Imaginary Sea), both Bianca Bondi and Lin May Saeed use unusual techniques and materials to ask questions about the ocean and humanity’s relationship with the natural world.

A whale skeleton, inverted and suspended beneath the foundation’s shimmering water ceiling, Bondi’s The Fall and Rise is the centrepiece of the exhibition. For the Paris-based South African artist, the work is the culmination of a practice that explores regenerative cycles and changes of state. Inspired by a whale fall, where the carcass of a dead whale becomes a complex ecosystem, sustaining life on the ocean floor for decades, The Fall and Rise offers a poetic, holistic meditation on natural life cycles. “The whale’s death is the beginning of so much more life,” Bondi says, reflecting on the piece’s reference to religious iconography in the Christ-like pose of the whale, with the skeleton ascending into the sky. “It’s like a resurrection.”

“To descend to the galleries feels as if you are diving into a submarine world”

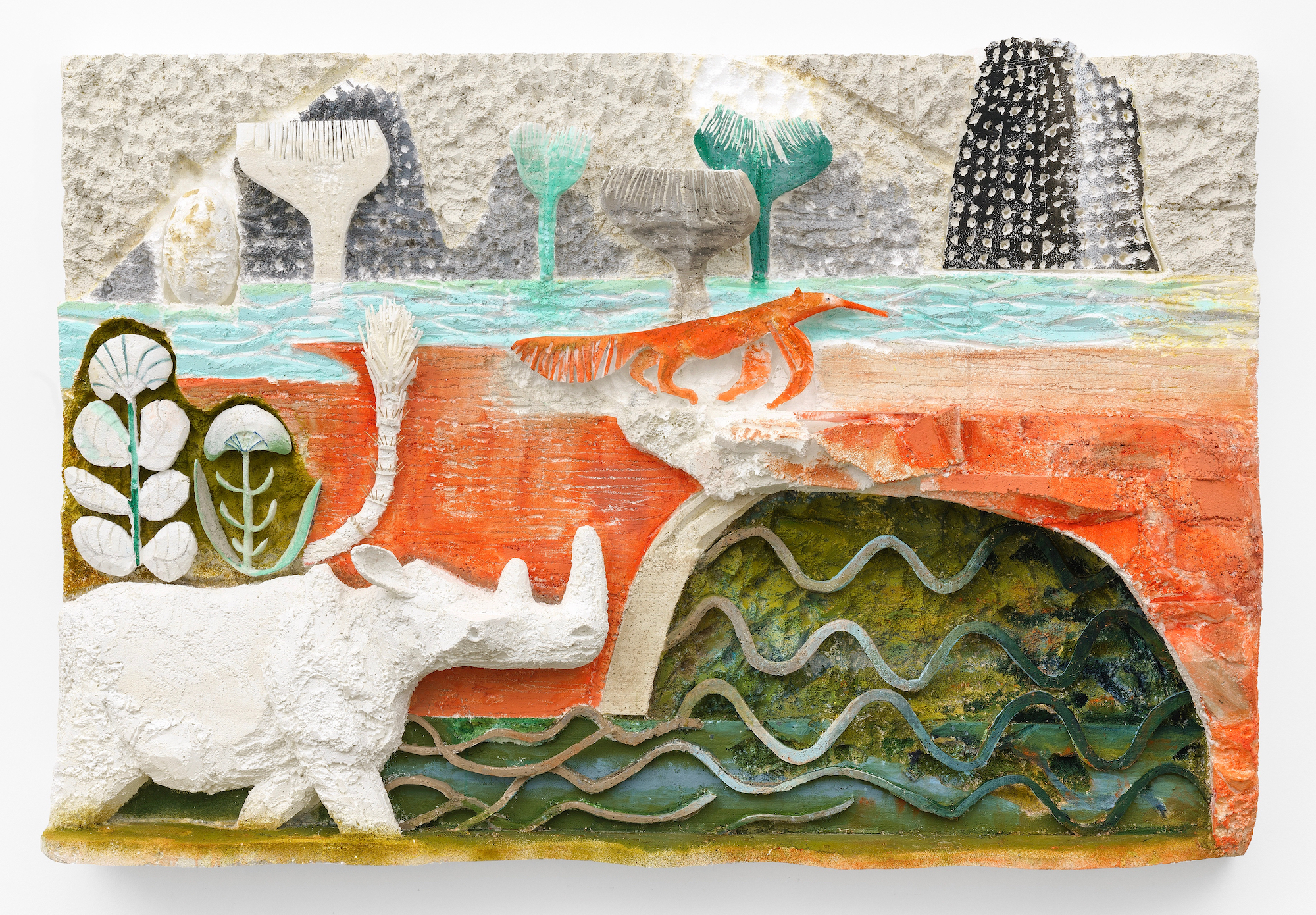

Saeed’s work takes a similarly long-term perspective, though she focuses more specifically on the relationship between the human and non-human. In Sea Dragon Relief, the colourful, improbable forms of sea dragons float serenely and indifferently past black linear structures carved from Styrofoam that suggest a submerged, post-apocalyptic world. Our sense of scale is playfully distorted here: manmade objects could be taken for fragments of skyscrapers, but are diminutive in comparison to the sea dragons. The work hints at a time after human presence on earth, beyond the Anthropocene, and the millions of years that it took for the sea dragons to evolve into their incredible form.

American curator Chris Sharp conceived the exhibition as a kind of artistic natural history museum. Guided by a sense of ‘solastalgia’ (an ecologically-driven nostalgia for a natural landscape that has not yet disappeared), the exhibition spans more than 100 years of artists’ responses to the sea.

Henri Matisse’s Polynêsie le Ciel (1946) and Acrobat (2003-9) by Jeff Koons sit alongside images and moving image works by French filmmaker Jean Painlevé (whose pioneering documentation of the submarine world in the 1930s inspired the Surrealists), and sculptural pufferfish by American artist Michael E Smith. Gabriel Orozco’s polyurethane Spumes (2003) (slowly hardening sculptures which take on the appearance of mysterious sea life), paired with the Matisse tapestry, are “future ghosts of the sea”, as the foundation’s director Charles Carmignac puts it, representing species that will become extinct because of human activity.

All of Lin May Saeed’s work is informed by her work as an animal-rights activist, a political standpoint that feels particularly relevant in the context of this exhibition. “The work that I do is driven by some very simple questions,” she explains. “Why, for example, do we call everything that is done by animals ‘natural’, and everything done by humans ‘artificial’? What does that say about us?”

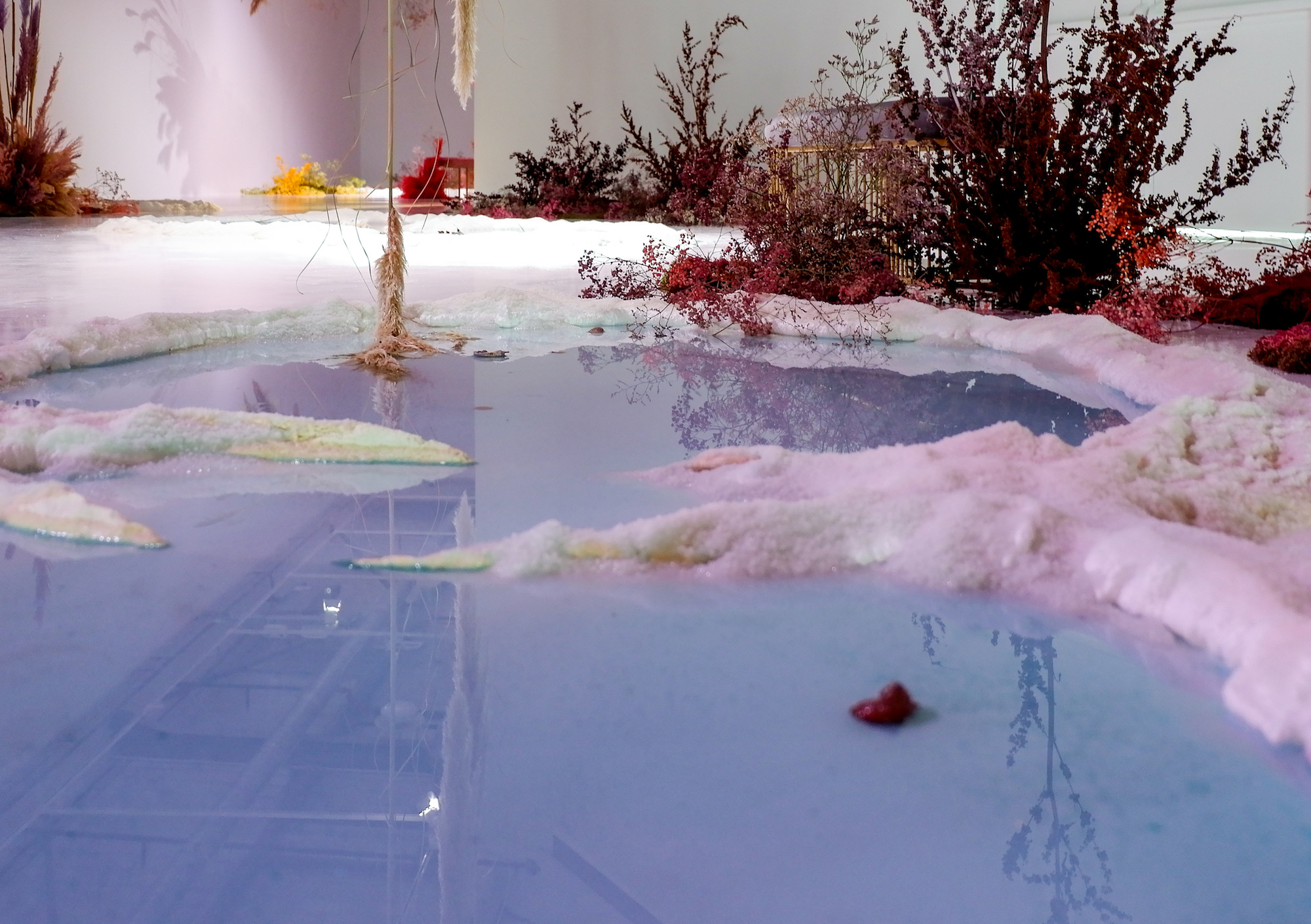

Bondi similarly foregrounds natural processes in her work without the distinction between the human and the non-human. Her immersive installations use crystallisation, oxidation and erosion to introduce processes that go beyond the singular agency of the artist. “The more you try to control something, the more things go out of your control,” Bondi says. “It’s not completely random, it’s more, as you say in French, laissez vivre, just letting things be.”

For The Fall and Rise, Bondi crystallised resin bones using inflatable swimming pools she set up in the gallery. Animated by the sunlight as it comes through the water ceiling, and with Bondi hoping to continue the process of crystallising the skeleton after the exhibition closes, the artwork is a living, changing thing.

An unorthodox approach to materials also characterises the work of Saeed. The Berlin-based artist began using Styrofoam for practical reasons, as it was lightweight enough to allow her to work on a large scale in her third-floor studio without needing assistance. The resulting relief works, in which the artist gouges into the surface of the foam, at times recalls classical narrative sculpture, part of a grand artistic tradition that spans centuries. But in the place of marble or bronze, Saeed’s medium is utilitarian and artificial. Developed for use as building insulation, Styrofoam is a form of plastic that will never degrade and decay. The contrast of this synthetic material with her depictions of animals and scenes from the natural world reveals, as she says, “the fallibility of our species. It is the epitome of humanity’s propensity to do something without understanding the consequences.”

“The colourful, improbable forms of sea dragons float serenely and indifferently past black linear structures carved from Styrofoam”

The Villa Carmignac opened in 2018 as the Paris-based foundation’s second space, carefully converted from a villa in the heart of the island’s protected pine forests. To comply with the regulations that control building in a national park, the vast galleries have been excavated from beneath the original structure. While the island itself is only accessible by boat, the subterranean space further encourages a meditation on the sea and our relationship with it. To descend to the galleries feels as if you are diving into a submarine world, and “a dreamlike space,” as Saeed describes it.

As you surface from the exhibition at the Villa Carmignac, blinking in the Mediterranean sunlight, there is a greater awareness of the other, hidden ecosystem evoked in Bondi and Saeed’s work. Both artists examine our disconnection from the realm of the non-human, and the ease with which we exploit that unequal power balance. In highlighting and untangling these natural processes and cycles, they suggest a humbler, more constructive way to coexist with the natural world.

La Mer Imaginaire (The Imaginary Sea)

Villa Carmignac, Porquerolles Island, until 17 October 2021

VISIT WEBSITE