On the banks of the Moskva River in Moscow’s trendy Red October district stands a handsome pre-Soviet era power station with a cream façade and two towering chimneys, owned by the private Russian V-A-C Foundation. The building, known as GES2, and the surrounding area will open in 2019 as a vast cultural hub that promises to transform Moscow’s art scene as dramatically as Tate Modern did London’s.

The V-A-C was founded in 2009 by Leonid Mikhelson, recently named as Russia’s richest man, to support and promote Russian contemporary art within an international context and is fast becoming a force to be reckoned with. The V-A-C has quietly supported the past four Venice Biennales as a donor, collaborated on shows at the New Museum in New York, and staged a series of memorable exhibitions with the Whitechapel Gallery in London. Now it is setting down permanent markers with a newly inaugurated four-storey palazzo in Venice and the GES2 power station in Moscow. Yet mention the V-A-C to most people in the art world and you’re likely to get blank looks.

“I think this world needs visionary and crazy people otherwise we will get Brexit, Trump, Berlusconi”

“They’re very mezzo-mezzo. It’s a very measured approach to everything and not bombastic at all,” Whitechapel Gallery director Iwona Blazwick tells me during a trip to the Russian capital to attend a music and art festival at the power station staged by the V-A-C. “Theirs is a dynamic collection and it’s growing,” she continues. “It’s not bought with a view to its worth in the future, it’s got a completely rigorous intellectual, scholarly and aesthetic core to it. I think that they see it as a tremendous way of brokering cultural relations with different parts of the world.”

The driving power behind the V-A-C is its director, Teresa Iarocci Mavica, a dynamic Neapolitan on a mission to educate people about art, nurture Russian emerging artists and foster cross-cultural exchange. Hailing from a family of communists, Mavica arrived in Moscow in 1989 to study economics with a view to a career in academia but was soon drawn to the freedom of the art scene.

Now she and Mikhelson are creating a cultural cathedral from GES2 that will be free for everyone when it opens in 2019. When I ask about her plans for the two-hectare site, currently being reconfigured by the Renzo Piano Building Workshop to comprise a grand piazza, sculpture garden, birch forest and multiple exhibition and learning spaces, she cites Pericles’ desire “to leave Athens better after me”.

“My idea of politics is the idea of big culture. Everything is linked,” she explains. “And that’s why when Mr Mikhelson put me in front of the power station I thought, ‘Wow, this is the agora. This is the piazza. This is the place where that kind of politics should be explained, should be exhibited. The politics which means participation. Which means to stay together. Which means to make this world better and better.’”

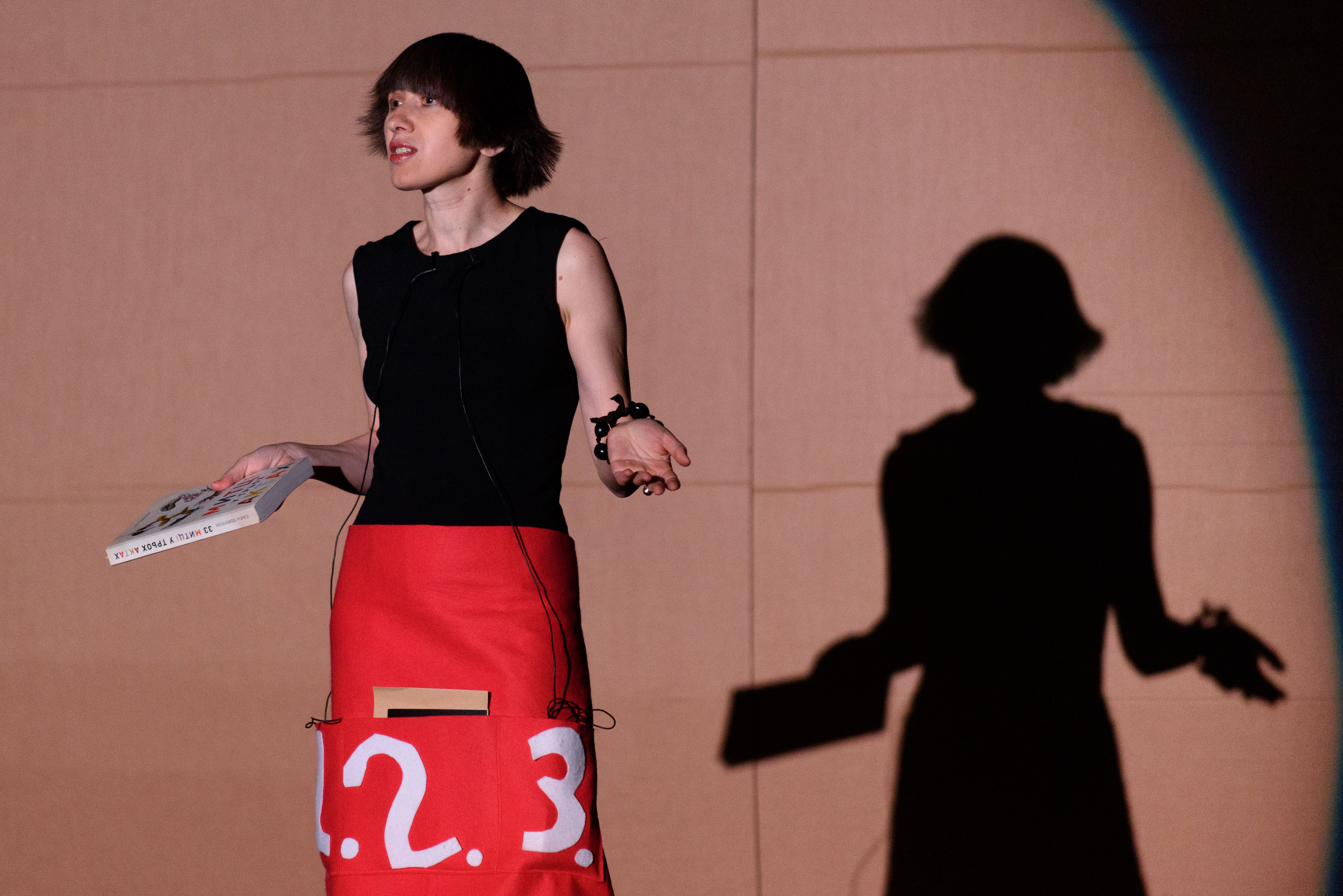

Earlier this year the V-A-C gave Muscovites a taste of what will be on offer with a world-class festival of electronic music and art called Geometry of Now in GES2. For a week the power station was turned into a site of sonic experiment where people could watch challenging musical performances, party to cutting-edge DJs and engage with site-specific installations across the building’s raw industrial spaces.

Marking a pivotal moment in the structure’s transition after the turbines had been removed and before work began on converting the space, the festival brought together around fifty Russian and international musicians and artists who work with sound. Thrilling and thought-provoking rather than easy-listening, the programme was curated by the British multidisciplinary artist Mark Fell and ranged from a seminal piece by French minimalist composer Eliane Radigue to a mesmerizing dance performance by Alexander Kislov to a DJ set by the dub reggae legend Lee “Scratch” Perry.

“It was a very judicious and strategically brilliant way of introducing the space because it was done with hardcore sound art. It wasn’t ingratiating, it wasn’t like going into a club,” says Blazwick. “I just thought that’s such a clever strategy of getting people involved, putting it quietly up on the landscape and now people will want to watch it grow and be involved when it’s fully open. It will be theirs.”

“She has a really democratic vision of giving this power station to destroy the exclusivity around art and to bring audiences into the space”

This commitment to bringing art to everyone is emblematic of Mavica’s approach and is illustrated by an anecdote from the festival’s curator, Fell. While he was scoping out the power station he discovered a tiny grubby workers’ canteen up a flight of stairs in the monumental central nave and hit upon the idea of hanging there the V-A-C’s prize painting by Wassily Kandinsky. It seemed an apt gesture to include Kandinsky as a pioneer who brought together the sonic and the visual and to communicate that art is not just for a museum-going elite. Expecting to be turned down, Fell proposed the idea to Mavica, who immediately said, “Let’s do it, I’ll talk to the conservation people.” Fell was amazed. “She has a really democratic vision of giving this power station to destroy the exclusivity around art and to bring audiences into the space.”

The Kandinsky painting, titled Dramatic and Mild (1932), has further significance for the V-A-C. It was the first artwork Mavica acquired for the foundation once she had persuaded Mikhelson to stop collecting nineteenth-century Russian painting and instead target modern and contemporary art. Mikhelson, whose fortune is based on natural gas and petrochemicals, met Mavica at the Venice Biennale in 2007. The brutally frank but abundantly charismatic Mavica recalls her response to his initial suggestion that she run his private collection: “I told him: ‘I’m not interested, first because it’s a horrible collection, second because it’s private. I don’t think you are in a position to have a closed private vision of the world. I believe we have to share, let’s work for everybody.’ I explained that people like him have this responsibility before society.”

Bit by bit, Mikhelson became convinced by Mavica’s arguments and, acknowledging that much of the best modern art was already in museum collections, turned his focus to the contemporary. The foundation was born with Mavica at the helm. V-A-C is in fact named after Mikhelson’s daughter, the acronym standing for Victoria, the Art of being Contemporary, while Mikhelson himself eschews the limelight. Victoria, who trained at NYU and the Courtauld, is now starting to take the reins at the recently formed live strand of the foundation, V-A-C Live. Geometry of Now was V-A-C Live’s first event in the “motherland”, she says jokingly, and was co-produced by herself and Mavica’s daughter Greta. “The aim,” she tells me, “was to connect what I feel is not yet very well connected in Moscow, different art fields, where people meet and can come and not only see what they’re interested in like opera but also see how it can be connected to a painting.”

“The aim was to connect what I feel is not yet very well connected in Moscow”

Mavica shares Victoria’s concern with broadening Russian tastes and creating dialogues across disciplines. Under her stewardship over the past eight years, the V-A-C has staged pedagogical shows at non-art spaces such as the Central Armed Forces Museum, the Presnya Historical Memorial Museum and the Institute for African Studies, Moscow. When I visited, they had a show by a young Russian art collective at the Gulag History State Museum, which looked at the economy of the Siberian tundra as a way into the fraught subject of the gulag

Abroad, the V-A-C has been involved in numerous exhibitions bringing together Russian and foreign artists, such as Future Histories with Mark Dion and Arseny Zhilyaev at Casa dei Tre Oci in Venice in 2015 and Ostalgia in 2011, curated by the New Museum’s Massimo Gioni and featuring more than thirty artists from across Eastern Europe and the former Soviet republics.

From 2014 to 2015 the Whitechapel Gallery hosted a series of shows with the V-A-C, inviting the artists Mike Nelson, Fiona Banner, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and James Richards each to create a room in response to the collection. The cross-cultural fusion yielded electrifying results.

“What was really astonishing was the total carte blanche that we were given and that the artists were given, as museums can’t traditionally take those risks,” notes the Whitechapel’s Blazwick. “It was so radical in curatorial terms, it really offered a whole new perspective on how you could work with a collection and for our London audiences.” Capitalizing on the success of the Whitechapel shows, Blazwick and V-A-C Live have agreed to showcase Russian art in London annually for the next five years.

In this way, through a carefully conceived programme of experimental exhibitions, events and workshops, the foundation has steadily, discreetly extended its influence. One senses, though, that things are about to change: the V-A-C is poised to become a name on everyone’s lips as it opens big new spaces—with free admission—in Venice and Moscow.

“It was so radical in curatorial terms, it really offered a whole new perspective on how you could work with a collection and for our London audiences”

The V-A-C launched its Venice headquarters, the Palazzo delle Zattere, during this year’s biennale with a thought-provoking exhibition, Space Force Construction, to mark the centenary of the 1917 Russian Revolution. The show, which then travels to the Art Institute of Chicago, considers through contemporary eyes the international exchange of ideas opened up by early twentieth-century Russian artists.

Perhaps surprisingly it proved a much bigger bureaucratic headache to get the V-A-C’s Venice headquarters up and running than to take on a heritage monument in Moscow such as the GES2 power station. Mavica has spent the past year and a half cutting through red tape in her native Italy, whereas in Russia, where the emphasis of state cultural policy is on preserving tradition, the Moscow mayor and a host of ministers attended a presentation on site, went through the plans with a fine-tooth comb and signed the project off there and then. “Here I got the maximum support and all of them know that we are not going to open a museum to show Michelangelo,” says Mavica.

That’s something of an understatement when one thinks of the transgender multimedia producer Terre Thaemlitz’s recent presentation Soulnessless(Cantos I–IV) at the Geometry of Now festival. The compelling work explores gender, sexuality, religion and sound and includes explicit video footage of a vaginoplasty procedure—this in a country where there are laws banning the propagation of homosexuality and attitudes around gender issues are far from enlightened. “You have to have guts to show this here. For Russia it’s very radical,” says the artist Sergey Sapoznikhov, who has participated in numerous V-A-C exhibitions in Russia, including the festival, and abroad. Indeed, when Thaemlitz brought Soulnessless to Russia in 2012, police shut down the venue; this time around, Mavica put a hundred guards on the doors to check visitors were over eighteen in accordance with regulations and everything went without a hitch. Moreover, in line with the V-A-C’s mission to educate, the festival’s curator, Fell, ensured the rich lecture programme included a scholarly discussion with Thaemlitz around gender, politics and queer culture.

It’s a good example of how Mavica operates. She doesn’t believe in flouting the rule of law, however disagreeable. But she does believe in the power of dialogue to achieve change. And when laws stand in her way, she works to change them. At the moment the irrepressible director has in her sights a Russian law from 1993 stipulating that art that is less than fifty years old is a luxury and requires payment of a 40 percent import tax.

“What was really astonishing was the total carte blanche that we were given and that the artists were given, as museums can’t traditionally take those risks”

“This is the reason why we do not have auction houses working here, this is the reason why we do not have collections developing here,” Mavica says. And this is why, when we visited the V-A-C private gallery on Mikhelson’s estate outside Moscow, we found just a tiny proportion of its high-calibre collection there. On display was an impressive array of Alighiero Boetti works in a wonderfully fluid dialogue with a school of Philippe Parreno’s colourful helium fish balloons that bobbed through the space, nuzzling indiscriminately against people and art. In the storeroom we saw works by Gerhard Richter, Sarah Morris, Yinka Shonibare, Farhad Moshiri, Sapozhnikov and Rudolf Stingel, but most of the collection is held abroad. However, after a year and a half of working with lawyers, Mavica believes she is close to achieving change.

“Sometimes when I’m talking to Mr Mikhelson he says, ‘You are too romantic. You want all the people to live together and love each other. This is impossible, this is quite crazy and visionary.’ Yes, maybe it is. But I think this world needs visionary and crazy people otherwise we will get Brexit, Trump, Berlusconi.”

Amen to that.

This feature originally appeared in issue 32

BUY NOW