For all the thought and care put into public displays of art by cultural institutions, it is surprisingly rare to find that same consideration applied to their most essential offering of all—the toilets. In the case of easily accessible galleries located in busy parts of the city, these facilities will undoubtedly be the most visited section of their building, providing a much-needed public service for all. Many a hapless picnicker has dashed into the Serpentine Gallery to relieve themselves after a bottle of wine in the park, or nipped into the National Portrait Gallery for a piss while wandering through Trafalgar Square.

One of London’s greatest attributes is the multiplicity of its free exhibitions, from the permanent collections at Tate to the National Gallery. It reflects an openness and generosity about the city—one that extends to its ready supply of publicly accessible gallery toilets. Why is it, then, that galleries and museums consistently overlook their washrooms? With hundreds, if not thousands, of bums on loos each day, is there any greater or more captive audience to be found?

Maurizio Cattelan’s solid gold throne, wryly titled America, has propelled the toilet-as-artwork into the headlines in recent weeks. A comment on the state of the nation (Cattelan initially offered the work to Trump for the White House), on greed and ostentatious displays of wealth, the work also recalls the absurdist provocation of Duchamp’s urinal back in 1917. When it was ripped clean out of the wall at Blenheim Palace after just a few days on display, many wondered if its theft was part of a bigger joke, but the artist has confirmed that this was not a prank.

Even before it was stolen, the furore that the toilet caused—with 100,000 queuing for a go on it at the Guggenheim in New York in 2016—reveals the untapped potential for artists and institutions to engage with even their most basic facilities. At a time when galleries and museums vie for our attention with exhibition hashtags and advance viewings for influencers, might not a foray beyond the expected confines of the gallery be just what curators are looking for?

“Many a hapless picnicker has dashed into the Serpentine Gallery to relieve themselves after a bottle of wine in the park”

At London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, the replacement in 2017 of its formerly generic cafe with Margot Henderson’s glitzy Rochelle Canteen, where elevated British staples are served with aplomb, demonstrated the benefits of thinking beyond the exhibition halls alone. Sadly, the ICA’s revamp did not extend to its toilets, where cracked tiles, rusted radiators and plastic cubicles are liable to bring back bad memories of the school bogs. All toilets at the ICA are gender neutral, however, at a time when few other cultural institutions in London are yet to designate beyond male and female facilities.

Curious about the state of affairs elsewhere, on a wet and overcast afternoon I visited eight public galleries around central London to put their toilets to the test. I elected to use only toilets situated on the ground floor, which would be the most likely to be frequented by the general public. Of those that I visited, only the Tate Modern Turbine Hall and Hayward Gallery facilities included a gender neutral toilet (doubling as a disabled loo). All had disabled and baby changing facilities, although the disabled toilets were not always located at the closest point to the entrance—as was the case at Somerset House.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Barbican and Southbank Centre boasted the most unique and well-considered washrooms. With their respective modernist and brutalist histories, these institutions were designed as complete centres for living and working, where nothing was overlooked in pursuit of the optimistic city of the future.

“With hundreds, if not thousands, of bums on loos each day, is there any greater or more captive audience to be found?”

At the Barbican Centre lakeside café, much of the original design remains, from the brass door handles to a rather lovely engraving of a shoe on each tap with the instruction to press down. The male and female toilets are arranged symmetrically on either end of a concrete rotunda, with the stalls arcing gently round the curve. Space is tight, but rigorous design avoids these bathrooms feeling cramped—much like the apartments that populate the tower blocks above.

The Southbank Centre’s Purcell Building, meanwhile, gives a space-age feel with gridded white tiles lining the walls. Two hefty concrete monolithic columns offer a reminder of the original utopian vision for the entire Southbank development, which includes the Purcell Building, the Queen Elizabeth Hall and the Hayward Gallery, built during the 1960s on former industrial wasteland. The space given to the washroom is generously expansive, with an entire wall dedicated to a series of well-lit mirrors—perfect for bathroom selfies.

It’s all exposed white brick and stone terrazzo floor at the Royal Academy of Arts, with marble detailing around the sinks, although the mirrors are small and a little mean for its size. Its lack of cleanliness also lets the elevated design down. The toilets in Tate’s Turbine Hall are clad in small black tiles on floors and walls. Elegant and simple; large and well-equipped, it feels aligned with the efficient design sensibility implemented by Herzog & de Meuron throughout the building.

Over at the National Gallery, however, things start to go really downhill. Large black tiles are paired with mismatched cream ones and grubby paint; it all feels a bit like the bathroom of a tired country hotel. The National Portrait Gallery next door doesn’t fare much better. The toilets are sequestered away in the basement, cramped and narrow. The only saving grace is a full-length mirror on one wall, good for adjusting one’s outfit before heading out into the throngs.

“It seems that there is a disconnect between where the art world meets and where it shits”

Somerset House’s offering, located in its West Wing is worst of all: tired and worn, devoid of personality and unkempt, with old toilet rolls littering the floor. Worse still, just down the corridor at Spring (the in-house restaurant of Somerset House) there has been no expense spared on their lavish loos. The only difference between the two? The former is publicly accessible, while the latter is reserved for restaurant customers only. It is commonplace for the restaurant industry to pay close attention to their lavatories, recognizing them as an important part of their identity, but the art world is yet to catch up.

It seems that there is a disconnect between where the art world meets and where it shits. Even in an industry centred around aesthetics and self-presentation, the toilet is repeatedly overlooked. In 2016 Julie Verhoeven addressed this issue through a “hospitable” intervention at the WCs in Frieze London, transforming the bathroom—“probably the most egalitarian space within the whole event”—into a playful “total artwork”. Titled The Toilet Attendant… Now Wash Your Hands, she and several performers acted out routines of labour, cleaning the toilets and offering mints, perfumes and other goods to visitors.

Verhoeven is not the only one paying attention to the loos. The @artgallerytoilets Instagram account does just what it says on the tin, documenting the facilities of London galleries in all their bland and ubiquitous glory—with a focus on the variations in signage pointing towards the WCs. @artgallerytoiletroll on Instagram is simpler still. Billed as an account “observing the differences in toilet paper from art galleries, institutions and museums”, each post shows just a square of toilet roll paired with the name of the cultural institution it was taken from. The Wellcome Collection, Saatchi Gallery, Barbican and White Cube all make an appearance amidst toilet paper gathered from galleries all over the world.

The toilets might seem a trivial part of a gallery or museum, but they represent more than just the backside of the art world. The accessibility of an institution’s bathrooms can speak volumes about how open they are to diverse visitors, and their position on gender segregation in the loos can be equally revealing. Toilets also remind us of the pay and labour policies that various organizations uphold, from the gallery attendants to the cleaning contractors. There’s no place to hide in the bogs, and they shouldn’t be something that institutions wash their hands of.

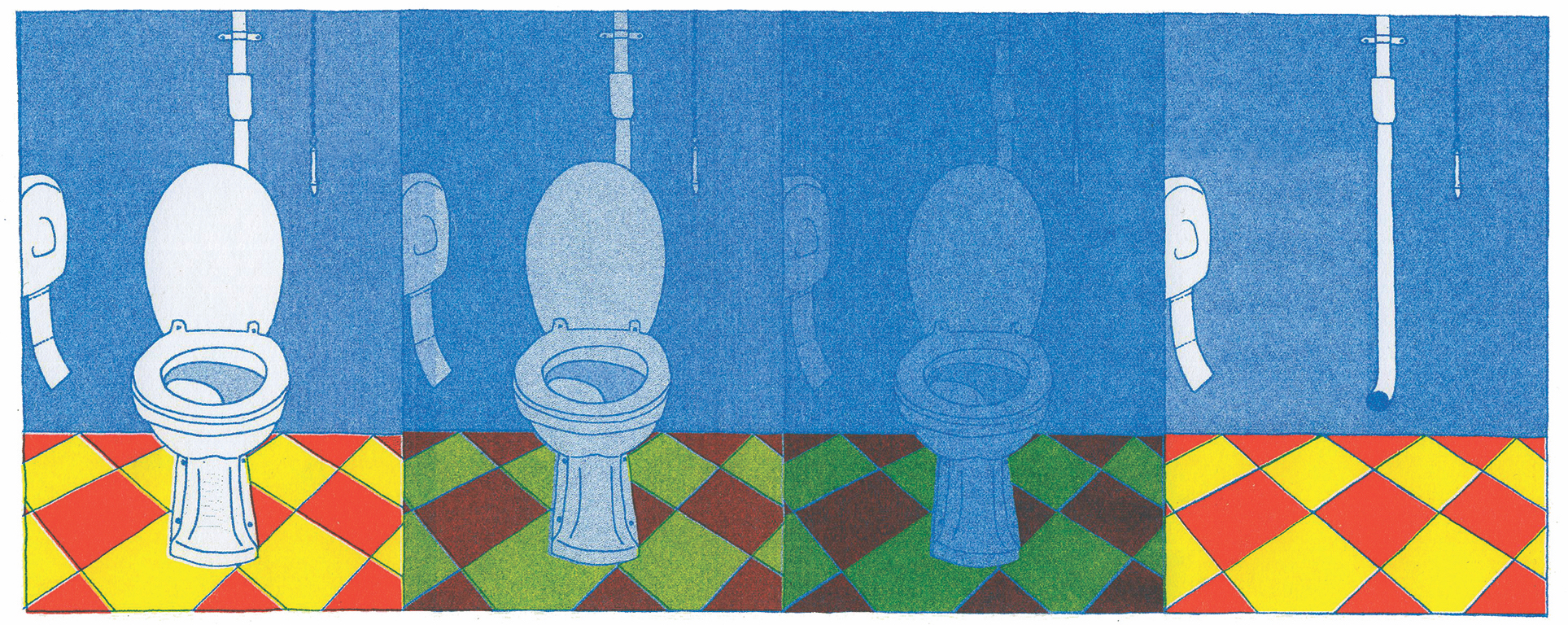

All illustrations by Antonia Stringer

Spotlight on London

Our five-part series explores the British capital and its creative communities.

EXPLORE THE SERIES