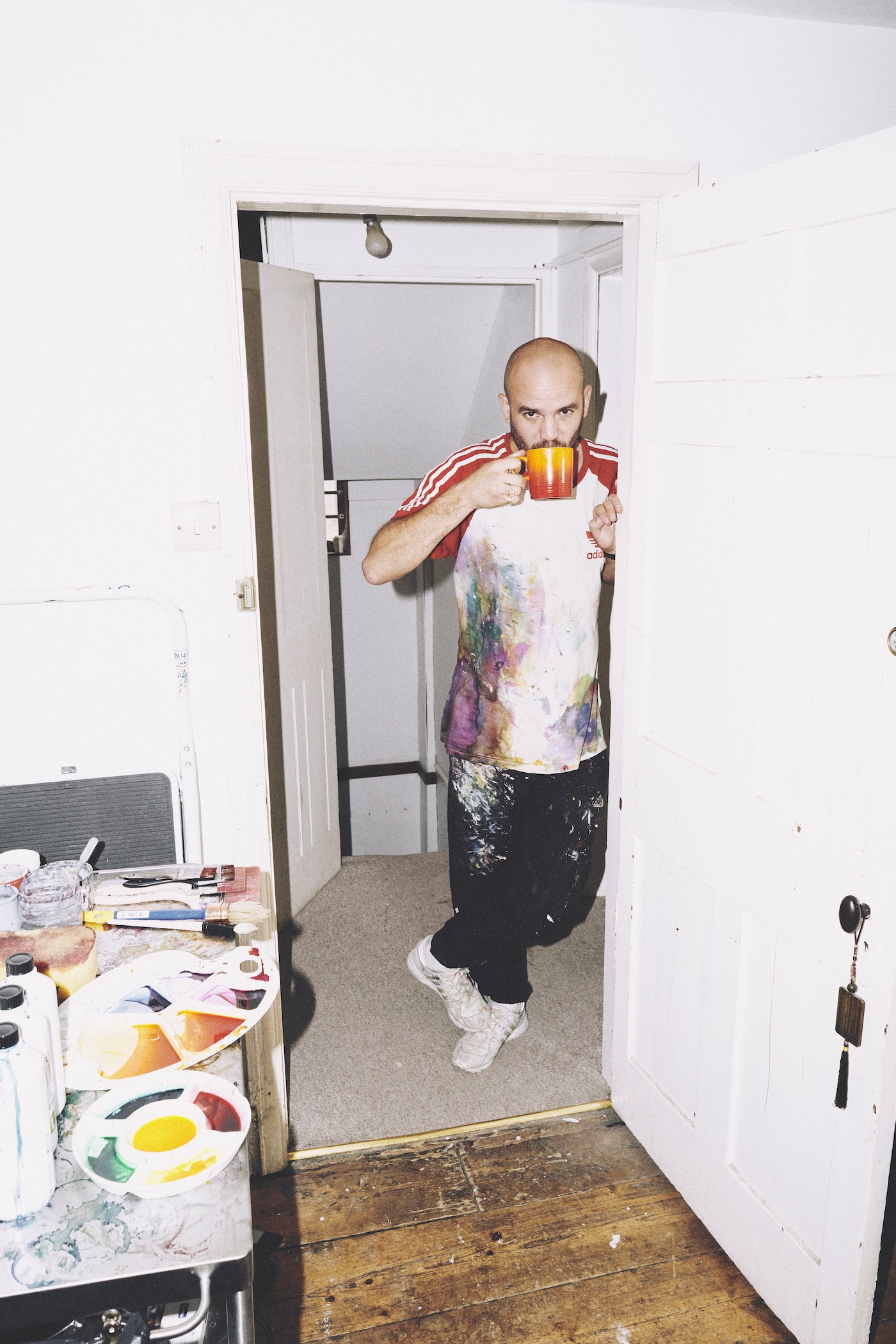

“How did you get in here?” Frank Laws greets me as I get to the top of a narrow staircase that leads up to his studio, in a townhouse on Kingsland Road, above where Seventeen Gallery used to be. On my way up, I pass piles of paper and rubbish stacked on stairs. The studio is cosy and warm, with two large windows looking down onto the street below. Perfect for someone who likes to spy on people.

I’ve visited Laws at his studio before, but this space is different from his previous white-walled space overlooking the canal. I’ve known Laws since he used to be involved with Le Gun, a collective founded by five RCA graduates in 2004, to promote their own work and their peers living in East London, in a post-crisis show of solidarity. Among the group, he was known as “Frankie Bricks”, for his love of painting buildings in fastidious, pristine detail.

There are lots of artists living in East London, but not many of them actually make work about East London, like Laws does. A fascination with brickwork first lead him to paint East London’s monumental housing estates, but he has also become one of the only artists to document buildings whose resident populations have changed dramatically. Since the 1980s right to buy, figures show that forty per cent of social housing is now privately owned. Laws doesn’t shy away from his perspective as an outsider, looking in; he ramps it up in lighting borrowed from a Noir film and the viewpoint of a voyeur. No people appear, but there are details that subtly speak of the people inside.

You used to have your studio over in the White Building in Hackney Wick. Why are you in this studio on Kingsland Road? It’s a room in, essentially, a house that was part of an old textile factory.

The owner of the building has his own office downstairs, surrounded by parrots and old fish finders he fixes up. It’s a really unique place to be. My friend offered this space to me before he sadly passed away, so it has a real sentimental value to it.

When do you usually come here?

I try and maintain office hours but usually I’ll get here about ten or ten-thirty in the morning and depending on the time of year, due to the natural daylight I’ll leave between four and seven. Summer time I’ve been going swimming about four, then come back to continue working until evening. If I’ve got a painting on the go I’ll usually arrive, set up by getting all my paints ready, get a tea stick on a podcast or music and then work till lunch about one.

“I guess my paintings ideally would be a vessel for discussion, awareness and not an answer or full stop”

What do you like about it here?

For me, I think it’s the homely feel and the sentimental attachment too. I really feel like I can sit in here all day and work. My last studio was huge in comparison but it was freezing and there was an industrial / factory feeling that was great if you were in the middle of working but when it was time to plan or do desk work it didn’t suit that.

I have to ask the inevitable. Why do you like painting bricks so much?

It developed from spending a year as a labourer (mainly brickwork) which led to an interest in the construct and how I could represent the amount of work that goes into the building in reality. It also has a therapeutic element to it, something calming in the repetitive and laborious side of it—for me at least. Having said that, I’ve recently stopped using them as an aesthetic tool as I feel actually they’re not adding to what I’m finding important and started to become just habitual.

You creep around East London like an architectural pervert—how do you decide what to paint and what’s the process normally like?

I don’t particularly have favourite buildings; it changes constantly. Though recently I’ve been walking around Stamford Hill, the Guinness Trust Estate. They really have a huge sense of nostalgia and history walking around there; they were completed in 1932. I normally decide first what I want to try and tell or represent in the painting. Recently it’s either very romanticized and nostalgic or, on the flip side of that, very monumental and powerful with a focus on the architectural element and feat. This is how I decide what to paint—I’m looking for something that specifically fits the bill. After that, I’ll keep revisiting and taking photos on my phone at different times of day until I have a collection of images to edit and work from.

There’s also an aspect of social inquiry in what you do that’s quite important to you. Looking at housing in London in a real way, especially after Grenfell, seems like something we should all be doing if we’re living here, considering what’s really going on in these buildings. Can you tell me more about that?

As housing is ever changing and things are being sold off and privatized, and the idealistic view of social housing is dwindling, I’m trying to convey a sense of nostalgia. It’s most certainly romanticized. I feel like I’m portraying a sense of history and memory that one day will be just that: a history and a memory. For me they are celebratory and not a negative statement or “grimy” or “poverty porn”, but it’s very much a spectator view and often depicted from the outside looking in. Though I have and I do live in these buildings, I’m still an outsider. I’m not a council tenant and I rent an owned flat, so these places were not built for my purpose, which in turn creates a kind of in-balance in what I’m trying to represent. However, I feel that’s very much the climate we live in and quite unavoidable. I guess my paintings ideally would be a vessel for discussion, awareness and not an answer or full stop.

“I’m trying to convey a sense of nostalgia. It’s most certainly romanticized. I feel like I’m portraying a sense of history and memory”

Your paintings also take a lot of patience, a lot of order—do you have to work alone, in silence? How do you react if you mess something up?

I often work to podcasts, audio books and also music. Working alone is good but I’ve always shared studios. I do like having people come by and also use the space sometimes, which breaks up the monotony. A lot of the time mistakes can be fixed, even though I paint mostly in liquid watercolour. Recently, I accidentally put a huge smear of an acrylic in the middle of a painting and had a complete meltdown, which feels ridiculous in the grand scheme of things but in that moment it’s really hard to snap out of it and be rational. I had to tear a layer of paper off and match it back in; it’s totally fine and now I feel stupid for being so dramatic.

Which exhibition that you’ve done to date are you most proud of?

I think the exhibition I done based on the Pembury Estate in 2014. It was put up locally (opposite the Pembury) and I collaborated with the youth club where they drew back over prints I had made of a Pembury wall. These were shown and sold alongside originals, and the locality of the show meant it was their show as much as mine. It just made the experience feel more engaged and involving the residents than just doing a workshop or an exhibition to one particular audience.

Your mum is also a painter, does she ever visit you here? Whose studio is better?

She is indeed, she’s been to see the studio, and she liked it but I definitely think she prefers hers and I prefer mine. Hers is in her garden and perfect for her, except think it gets pretty cold in there!

Photography by Benjamin McMahon