There’s a classic visual motif in cinema: a newspaper sheet, crumpled and contextless, blowing in the wind across a silent sky or empty street. It’s the urban equivalent of tumbleweed; those bumbling piles of dried invasive vegetation signify a vast and aggressively lonely wilderness, but the abandoned leaf of low-cost, low-gsm paper has more human connotations. It suggests cultural decay, material waste, and the random indifference of a complex social system. A homeless person might stuff it into their shirt for warmth, a detective might find a clue on it, a bird might make it part of its nest; the fate of the newspaper after the day is done is unpredictable and largely inconsequential.

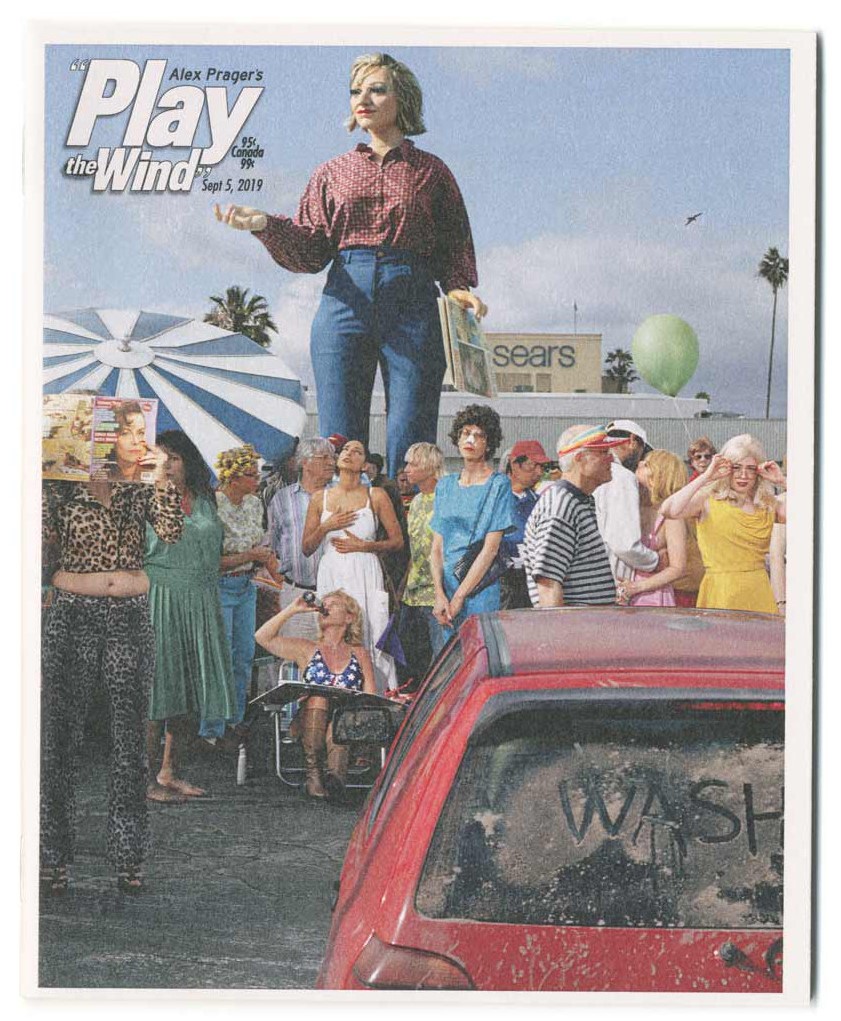

So what happens when the fundamental disposability of a newspaper meets the opposite of inconsequence: art? It’s not a coincidence that Alex Prager designed the catalogue for her latest body of work as a miniature novelty tabloid. Play the Wind examines nostalgia, narrative, and distorted memories, tied to the weirdly warped spacetime of Los Angeles. As well as being borderline archaic in this digital age, newspapers—especially tabloids—are geographically and temporally specific; they have limited lifespans, distribution, and coverage. They don’t tend to travel beyond their remit. Unless, of course, they are blown by the wind, or carried by a person with a story.

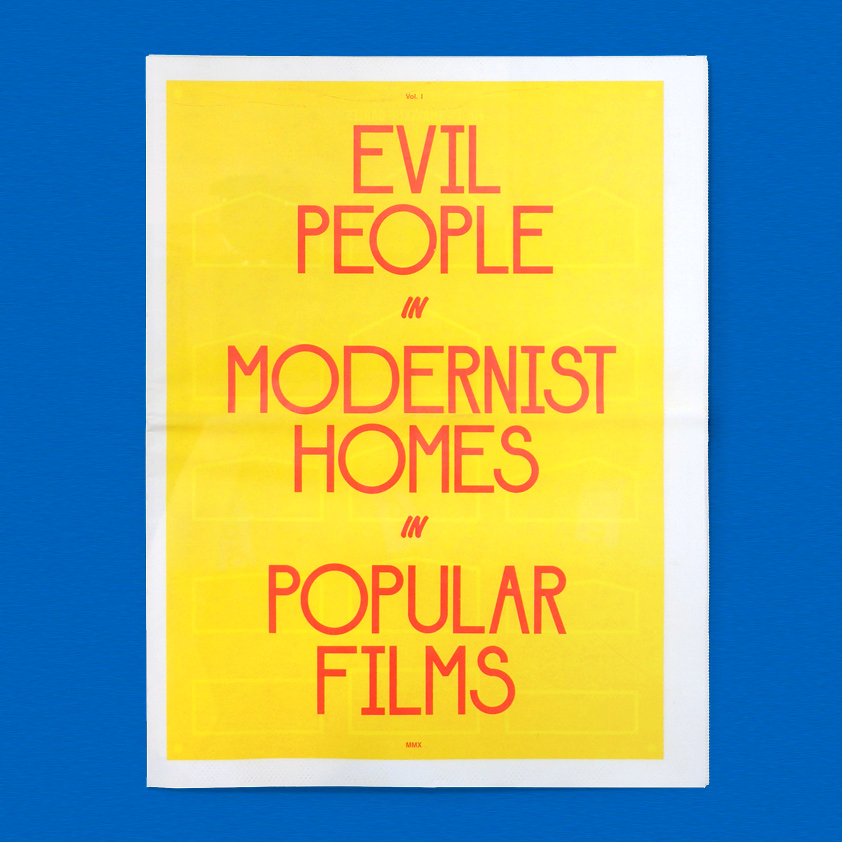

The practice of printing an exhibition catalogue, photo series, visual essay or other intermediate project onto flimsy newsprint is quietly common among multi-disciplinary artists and designers. The final products are often sold in accessibly priced but extremely limited runs and, once gone, become vanishingly rare, which makes them democratic but still desirable art objects. Almost anyone could have afforded a copy of LA-based artist Benjamin Critton’s Evil People in Modernist Homes in Popular Films—a simple yet revelatory collection of stills and text on popular cinema’s habit of housing villains, from Bond masterminds to sparkly vampires, in modernist architecture—but the edition of 1000 sold out quickly and is now practically impossible to find.

“The ‘daily disposable’ nature of newspapers has always sat strangely with the historical scale of the events reported within their pages”

At the same time, the non-archival nature of newsprint means the paper will inevitably oxidise, the pages will grow more brittle, the edges will tear, and general handling will crumple the paper, turning an iterative edition into a unique object, depending on how the owner treats it. Very few other things produced by artists are quite as ephemeral, and that ephemerality is, amongst other things, what makes newsprint publications an exciting format.

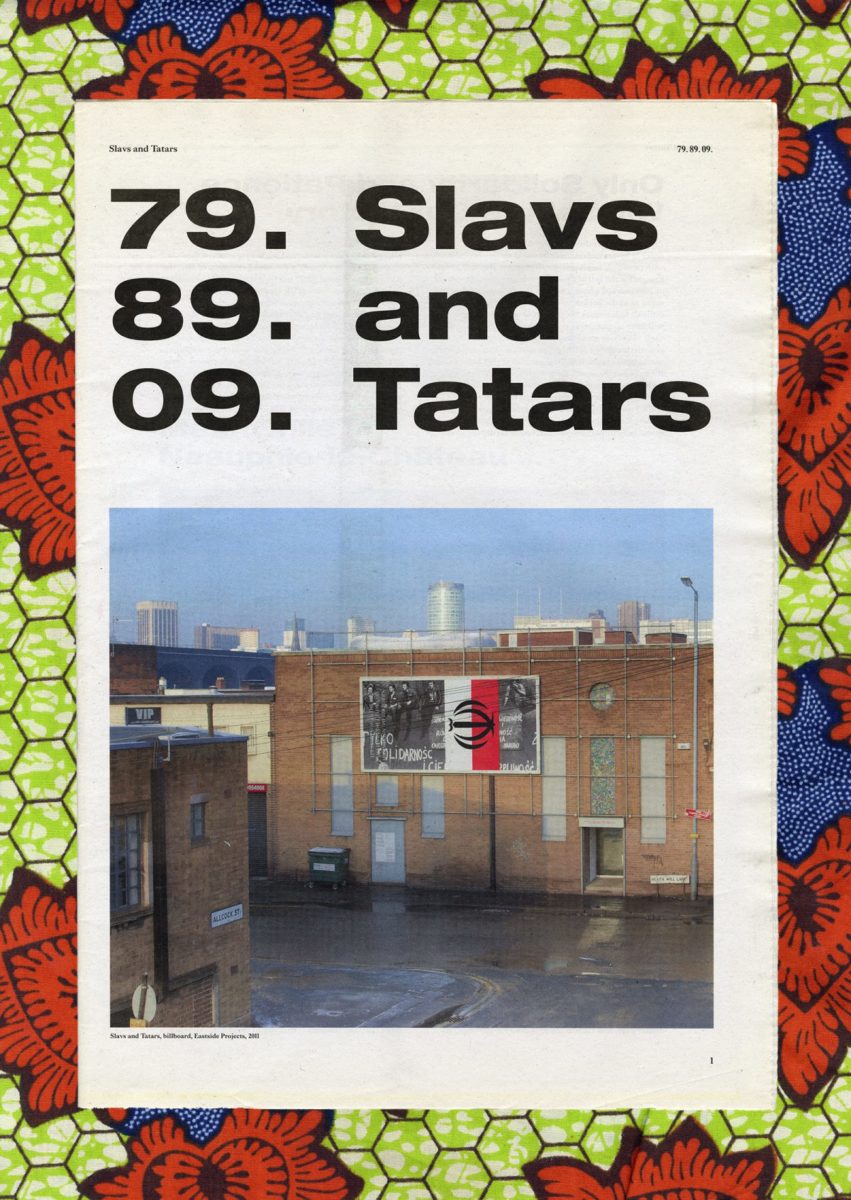

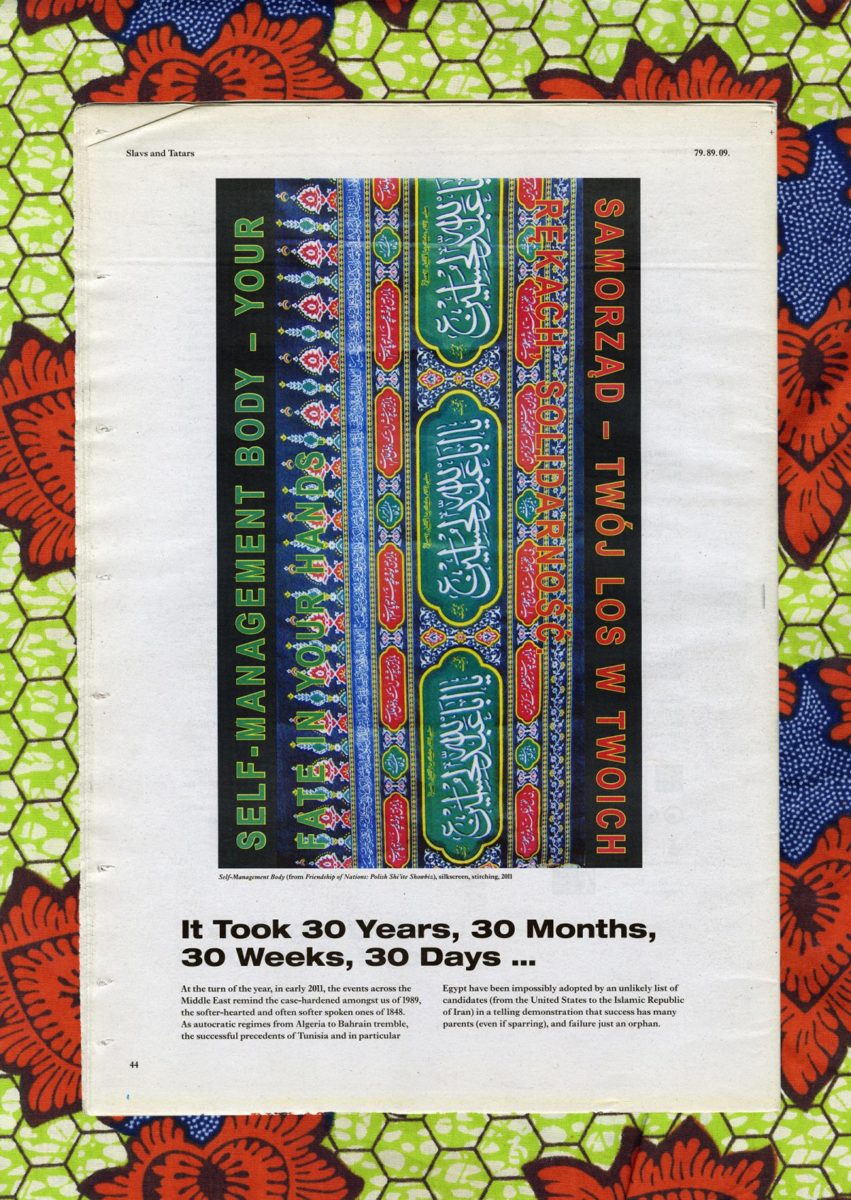

- 79.89.09 by Slavs and Tartars, 2011. Image by James Langdon courtesy of Eastside Projects

The “daily disposable” nature of newspapers has always sat strangely with the historical scale of the events reported within their pages. What is headline news one day can be relegated to historical footnotes the next. Posterity looks at things with a different perspective than the harassed editor in Howard Hawks’s satirical 1940 screwball His Girl Friday, who happily barks “Take Hitler and stick him on the funny pages!”

The artist collective Slavs and Tatars, a “faction of polemics and intimacies scattered throughout an area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China” probably had these paradoxes and entanglements in mind when they produced 79.89.09, a visual essay in the form of newspaper. The striking and humorous publication plays with the historical bookends of twentieth century Communism and twenty first century Islam, re-imagining Polish/Iranian solidarity in times of revolution. The publication also nods to the radical history of newsprint. Cheap two-process printing on flimsy stock has been a cornerstone of many a revolutionary movement, and many an oppressive state propaganda machine. Networks of information, propaganda, dissent, and entirely new ideas—the Surrealists had their newspapers, so did the Soviet Union.

Relations between politics and the press are still fraught today, with accusations of bias, slander, “fake news”, false statements, and of course tweets all flying about like a flock of particularly malicious seagulls on speed. Artists have responded to the current antagonistic, overloaded reality in various ways. Jet Nijkamp’s one-off tabloid Dress Like a Woman augments and alters the visuals that accompany the news, giving President Donald Trump a new and subversive wardrobe. Her attempt to impose a consistent concern on dozens of different publications illustrates the cacophonic quality of the daily media chatter.

“Artists’ newspapers can play with the relationship between representation and fact, art and culture, and time and space”

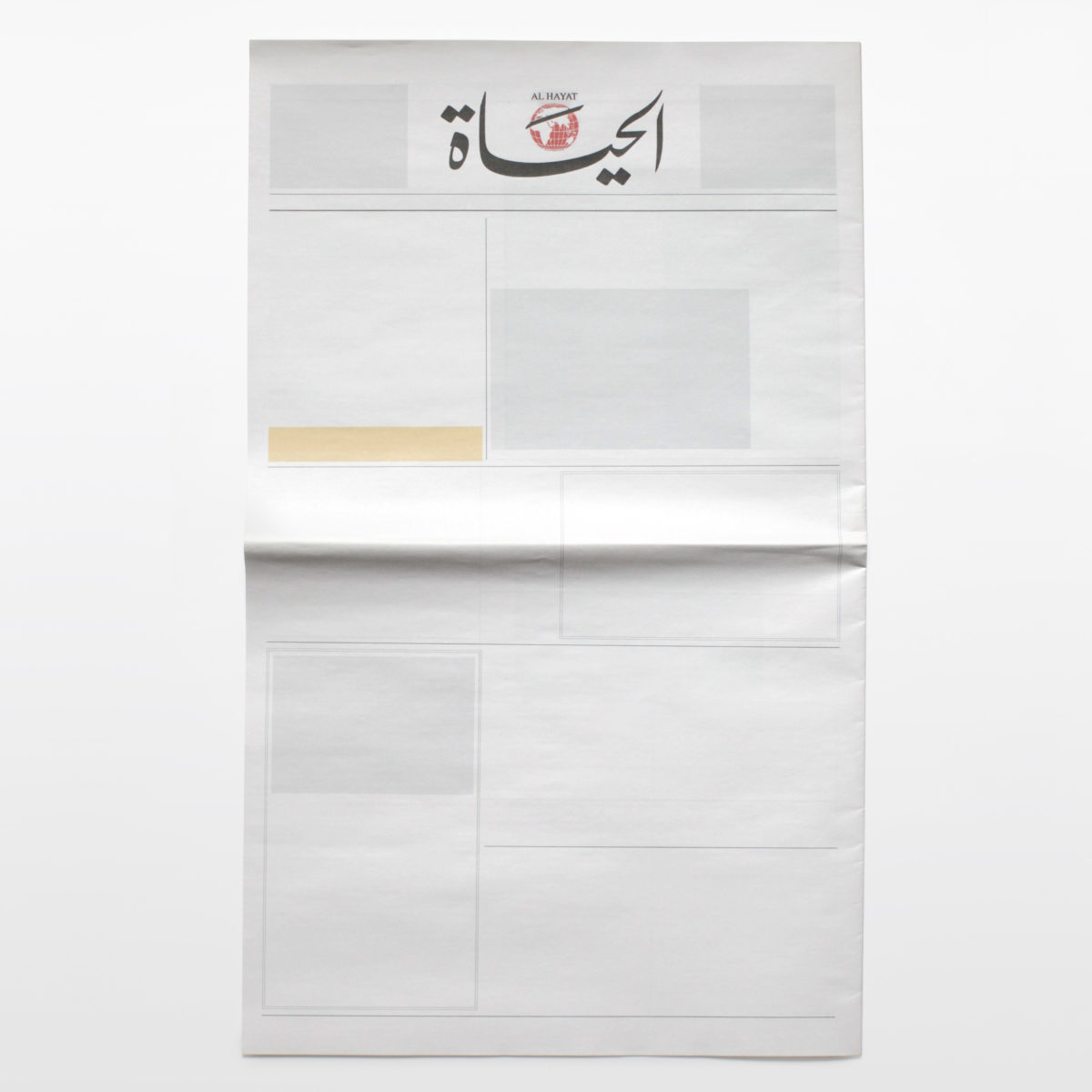

Taking the opposite tack, Joseph Ernst’s Nothing in the News offers us the fantasy of just one day where there’s no news. His series of empty newspapers, devoid of anything but some symbolic blocking and banners, do more than just take us back to 18 April 1930 (famously the day when the BBC’s radio announcer had absolutely nothing to report); they are an invitation to think about what news is, what counts as news, and what we want from our news. Do we want truth, or do we want answers? Is it the case that, in the words of author and former journalist Sir Terry Pratchett, “what people think they want is news but what they really crave is olds.” Do we want to be told that the world is the way we think it is, or that it is not?

- Nothing in The News. Images courtesy of Joseph Ernst and Sideline Collective

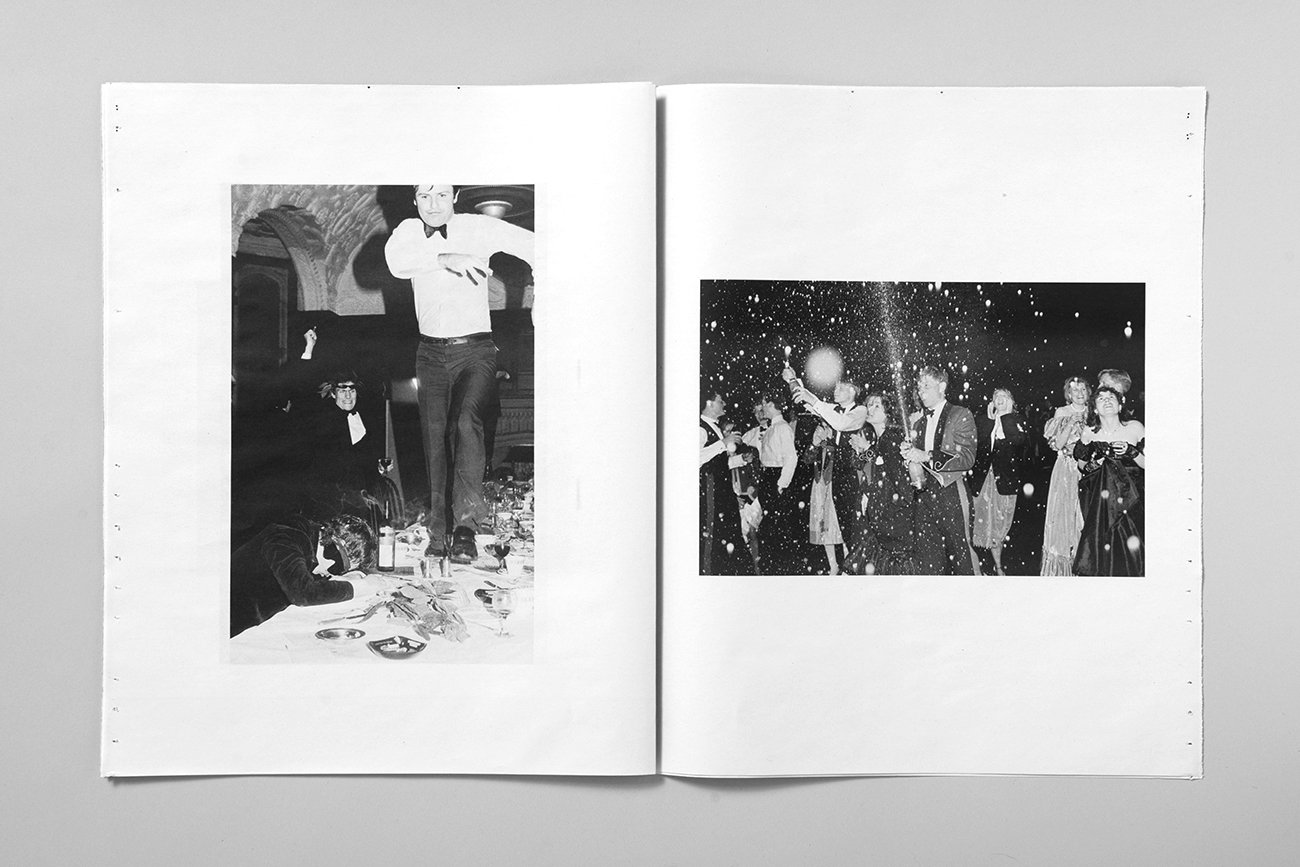

That question of representation is one all visual artists have to deal with eventually—are you showing people the familiar or the new; the new in a familiar way, or the familiar anew? In that sense, framing a story is not dissimilar to framing a photograph. This might be why the newsprint format has been so popular with photographers and publishers of photography looking to collect groups of images in a format that is neither book nor print, but something else entirely. From the magical dreaminess of Takeshi Suga’s Winter Wonderland to Alec Soth and Brad Zellar’s sparse but evocative LBM Dispatches, the newsprint invests geography with cultural, almost documentary, significance through its association fact and report. Meanwhile, collecting Dafydd Jones’s iconic photographs of aristocratic hedonism and hijinks in tabloid format The Last Hurrah nods at their proximity to society and scandal, but also at the ephemerality of the moments, times, and people captured in his perfectly timed shots.

As physical objects, as conceptual media and as receptacles of information, artists’ newspapers can play with the relationship between representation and fact, art and culture, and time and space. They might be more mobile and fragile than a sculpture, at risk of oxidisation and creasing, but art lasts longer than news, and artists’ newspapers are less vulnerable to entropy than yesterday’s Times. If one of these publications were to end up blowing down a quiet street, or across an empty sky, it’s not just a motif, it’s probably the story.