I have no head for names and faces. They slip through the frayed net of my mind, wriggling out into the ocean of things I don’t know. Every gallery opening is a gauntlet, every book launch an ordeal. Working as a critic—while justifying endless hours in solitude, and ensuring a diet of miniature croissants at press views—requires me to attend, even occasionally to host, these public events.

So I have developed strategies. Chief among them is a patter of generic familiarity, punctuated by questions calculated to uncover my mystery interlocutor’s identity (“How’s that project you were working on?”, “All well at home?”). Yet this approach is thwarted by people’s determination to talk about the trait by which they identify themselves (their love of plotless films from southeast Asia, their trips to godforsaken places) rather than that by which I and others remember them (their notorious drug consumption, their inclination to punch toilet mirrors after three cocktails). Human nature, I guess.

“Every gallery opening is a gauntlet, every book launch an ordeal”

At documenta 14 in Athens, I suffered two particularly painful encounters on the opening day. The first came after I bumped into someone I didn’t recognize but who recognized me. It transpired that she believed me to be her neighbour in Berlin (I made my escape by inviting her round for dinner next Tuesday). In the second, finding myself sat next to an artist whose name I couldn’t remember, I misdelivered a text message to a friend (“Name of terrible painter w [redacted] gallery we hate pls, urgent”) with career-damaging consequences. So in the evening, feeling bruised, I abandoned a dinner to celebrate the world’s most important survey of contemporary art to sit alone with a beer in a dusty suburban park. Here I was free of the possibility of social disaster. Instead, by perching on the left edge of a sun-bleached bench I was just able to glimpse, through a gap in the flowering lemon trees, the southeast prospect of the Parthenon. It was—and this is the level of critical insight you can expect from this column—very beautiful.

“If I were on Instagram I would post a selfie with Parthenon, accompanied by a caption: ‘My spiritual home! :P'”

If I were forced to substantiate this aesthetic judgment—by the editor of this magazine, to take a purely hypothetical example—I might note that the Parthenon is attached in my imagination to stories I’ve been captivated by since childhood. It is one of those iconic sites, like CBGBs or the Café de Flore, that are important to anxious provincial teenagers who dream of escape into an imagined international community of artists and intellectuals, a Foreign Legion for pretentious people. So even though I’ve never been there, the Acropolis is one stone alongside the Velvet Underground, the Manchester Free Trade Hall and Kurt Vonnegut in the fragile edifice of my manufactured identity. “Visiting the Parthenon” is the kind of thing I would say if someone asked me at a social event what I had been up to recently. If I were on Instagram I would post a selfie with Parthenon, accompanied by a caption: “My spiritual home! :P”.

It is a truism that Instagram is the medium through which the Digital Pictures Generation practise an everyday symbolism. We craft identities through the juxtaposition, via selfies, of our bodies with those things with which we feel or would like to imply a close affinity. It’s difficult to avoid the temptation, when writing about Greece, to resort to etymology but it seems pertinent here that “symbol” derives from symbolon, a piece of pottery divided into two halves. These would be reassembled when the two carriers met, offering proof of a relationship between the pair, an early precursor of those broken-heart pendants exchanged by psychologically stunted couples. This is the relationship we imply when we picture ourselves in front of things, when we place an artwork in a specific context, or when we situate an exhibition in a particular city. We suggest that there exists a kinship.

To Athenians, the Parthenon conjures memories of national disinheritance and resistance. In 1807 it would have been possible from my narrow bench to watch Lord Elgin’s men scrambling over the temple, chipping Phidias’ frieze into blocks bound for the British Museum (the gaps in the Acropolis Museum’s display make for a poignant, shameful symbolon). In April 1941 local residents might have gathered to watch German soldiers raise the swastika; a month later, a night-time visitor to the park might have glimpsed two nineteen-year-old students tearing it down. The German tabloid Bild continues to ask, provocatively, why the Parthenon should not be sold to repay Greece’s debts to Germany. The Parthenon is a reminder, if one were needed, that culture and politics are also two halves of the same thing.

Which might explain some of the tensions that surrounded and threatened to overwhelm documenta, a state-funded German exhibition that has never before ventured outside its home city of Kassel. That the artists, critics and curators who pilgrimaged to Athens for this vast survey of contemporary art were not universally welcomed by the local population was made clear by the graffiti scattered around the exhibition venues. “Crapumenta” was the most popular slogan. More elaborate stencilled protests declared that the people of Athens “refuse to exoticize [themselves] to increase your cultural capital” and, satirizing documenta’s high-minded progressive politics, that “it must be nice to critique capitalism with a 38 million euro budget”. An exhibition founded in 1955 to repair West Germany’s links to modernist European culture in the wake of Nazi barbarity, sited in a manufacturing centre heavily bombed by the Allies, stood accused of cultural imperialism and what Yanis Varoufakis has termed “disaster tourism”.

Yet Varoufakis also defended documenta’s right to be in Athens, protesting its perceived aloofness rather than its presence per se. I agree. In a Europe teetering on the edge of social and political fragmentation, the assumption that a cultural institution should be prevented from reaching across borders—however ham-fistedly—seems worryingly exclusionary. Moreover, the argument that documenta’s incursion into Athens was a straightforward expression of German soft power is flimsy: the artistic director was Polish, the relocation was resisted by the funding board, the list of artists was pointedly international.

“The German tabloid Bild continues to ask, provocatively, why the Parthenon should not be sold to repay Greece’s debts to Germany”

The furore surrounding the division of the exhibition between Athens and Kassel was not only entirely predictable, but essential to its stated aim of provoking discussion. The debate around cultural exchange between two EU member states, even and especially those otherwise at odds, introduces a broader question: What does it mean to be European? The implication that cultural institutions should not attempt to cross borders—that doing so is inherently disrespectful of a local scene—is symptomatic of the same jingoistic insularity that has recently blighted European politics. If there are to be political and economic solutions to the crises that threaten to fragment the continent, then they must be accompanied by the sense of communal identity that only cultural exchange can foster.

With the sun setting, I walked back to the terraced house on the hillside where I was staying, part of a bustling suburb crisscrossed by streets named after the philosophers. Seeing me come through the narrow courtyard, Katerina invited me for a glass of home-brewed tsipouro on the flat roof that serves as her sun trap and smoking area. A cat keened for her attention. Deftly rolling a liquorice cigarette paper around three pinches of tobacco, Katerina told me how the neighbourhood had changed since the euro crisis. An architect, she has lived in Mets for thirty years, and now rents outs the small annex to tourists. I asked why her English is so good; she read the poets when she was younger. We talk about Byron, who died a hero of the Greek revolution, and how he despised Elgin. We drank another glass, I told her about documenta, she laughed, we talked some more. I remember the angle of the sun as it set on us, and the pleasure of talking to this woman about the city and culture in which she lived. And the name of her cat comes to me: Anya.

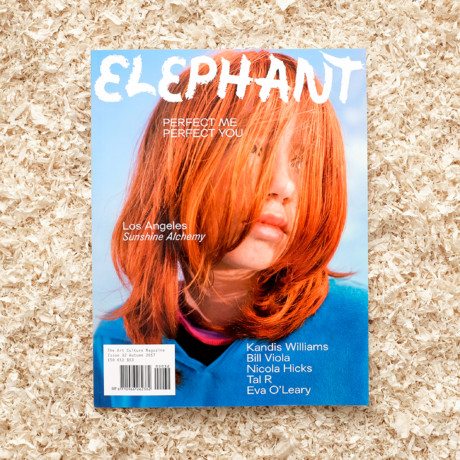

This feature originally appeared in issue 32

BUY ISSUE 32