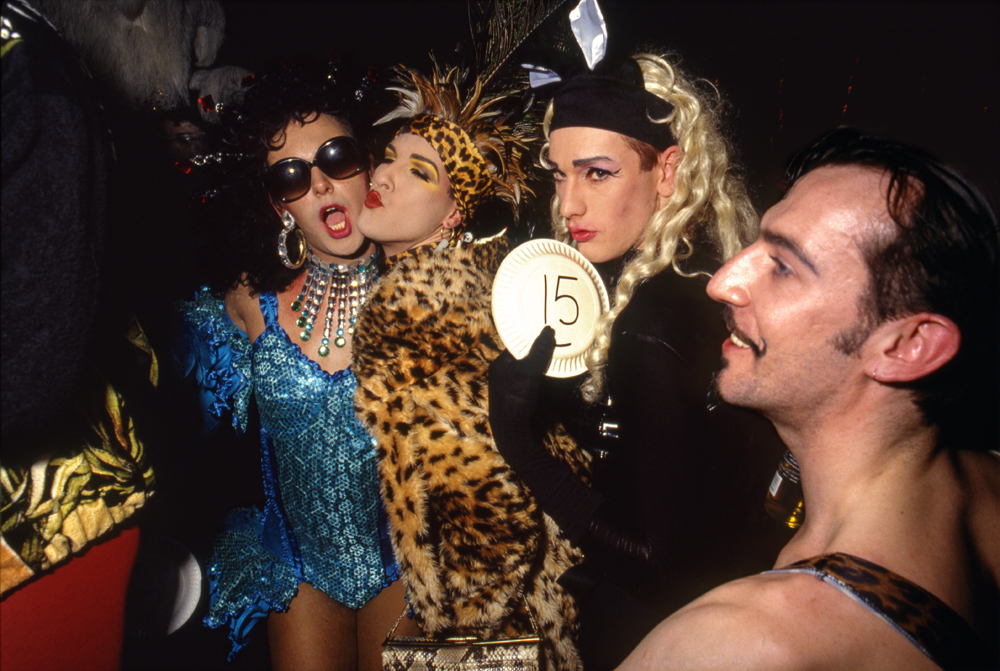

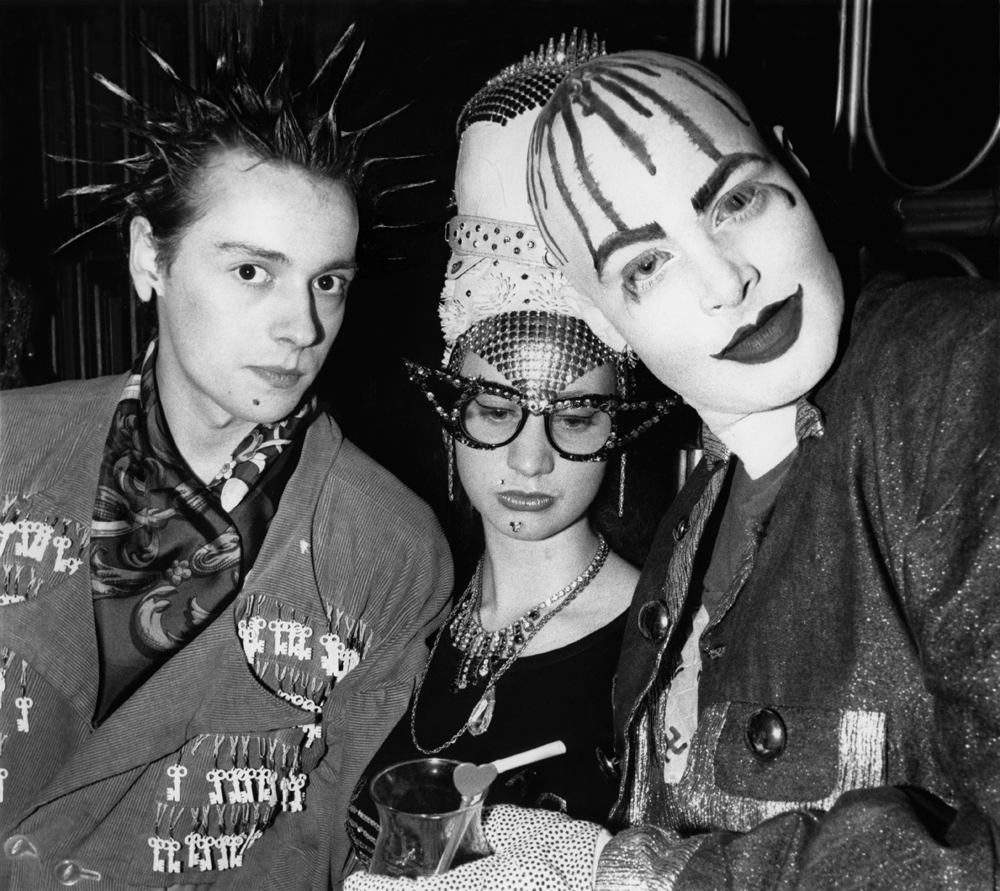

“Going clubbing in the 1980s was a form of performance art,” enthuses London-based journalist and photographer, Dave Swindells. “There were figures like Leigh Bowery who literally personified this. That side of club culture has always fascinated me, because it tends to make interesting, dynamic images…”

Club culture has been a way of life for Swindells; his vivid insights have illuminated decades of scenes from Britain to the Balearic Isles, and his images feature in the acclaimed Night Fever: Designing Club Culture 1960-Today currently on show at Vitra Design Museum in Germany. Swindells was also the nightlife editor at my first job, when I joined Time Out magazine as a young writer in the mid-nineties. It was a wildly exciting time to be out all night, and to shout about it the next day, whether you fancied clubbing to house, hip hop, jungle, indie or industrial noise. Music, art and fashion certainly had long-standing connections, but the dance floor was where worlds really collided—and transgressive new energies were spawned.

These days, the clubbing/art crossover has established its presence around global cities; “after-hours” programming is ubiquitous, from the Tate Lates series in London and Manchester International Festival’s nightlife celebrations, to MoMA’s PS1 Warm Up summer parties, or the midnight showdowns at Dallas Museum of Art. At its best, this convergence is both inclusive and experimental—but it’s worth remembering that until fairly recently, clubbing wasn’t widely acknowledged as “culture” at all.

“It’s worth remembering that until fairly recently, clubbing wasn’t widely acknowledged as ‘culture’ at all”

Cultural sociologist Dr Sarah Thornton (author of Seven Days in the Art World, and 33 Artists in 3 Acts) brought a uniquely incisive art history approach to nightlife in her 1995 book Club Cultures. While there was some excellent journalism about clubbing at the time (including seminal style magazine The Face), Thornton’s

perspective felt groundbreaking. There was also a random dance floor collision here for me; Thornton was an inspirational tutor at my university, and interviewed Swindells for Club Cultures, around the time that I first worked for him.

“In the 1980s and 1990s, when I did the bulk of my clubbing and club-research, few venues included work by ‘artists’ in the strict sense,” Thornton says, when I ask how she began to frame clubbing as a cultural study. “The Palladium club in New York was the jaw-dropping exception. My favourite spaces were the Goth upstairs bar, which featured candelabras and a 40-ft long canvas by Jean-Michel Basquiat (now the most expensive post-war artist) and the fluorescent graffiti telephone booths by Kenny Scharf.”

Thornton notes that while a Basquiat painting sold for $110.5million in a 2017 auction, his Palladium work was apparently destroyed in the late nineties, when NYU purchased the building. “It’s an indication of the lack of respect afforded to art when it’s not in a bonafide art location, like a museum,” she says.

Despite this, around the late-nineties, intriguing clubby undercurrents were also pulsing through the foundations of formal art institutions—and one vital instigator was Vivienne Gaskin, who would become director of live and digital arts at London’s ICA. Gaskin had previously worked with worked with visionary curator Joshua Compston at Factual Nonsense, whose Shoreditch “summer fetes” brought Young British Artist happenings into the public open space; the twentysomethings also began to see club culture’s potential for “democratizing” the gallery floor.

“My early experience of the ICA when I first joined (as memberships secretary in 1996), was that I was not of the right class,” says Gaskin. “Live art, though it was a very well-curated programme, was very much for the ‘insider’, rather than the general public. That division concerned me deeply. At the same time, experiments were happening outside; bars were transforming themselves into DJ venues and contemporary art was starting to trickle into the UK mainstream, particularly in London. The whole discussion of ‘low’ and ‘high’ cultures didn’t ring true.”

Although Gaskin didn’t initially have a curator role, she began to experiment with DJ-driven nights such as Scanner’s Electronic Lounge, and art/music collaborations with kindred spirits including Iain & Jane (in Iain Forsyth’s words, “Vivienne didn’t so much let everyone in through the back door, as nick the keys to the building!”). Another breakthrough came through the ICA club events hosted by art luminaries including the Chapman Brothers. “Suddenly, you’ve got Jay Jopling next to some kids on the dancefloor, while Tracey Emin plays Tiger Feet,” recalls Gaskin, laughing. “Art really does trail behind pop…”

During Gaskin’s tenure, the ICA hosted a range of revolutionary (and rammed) club nights in the late-nineties/early-noughties, including Raya’s multi-media hotbed, Batmacumba (where DJ Cliffy played new Brazilian drum ‘n’ bass alongside archive gems, and clubbers could also watch experimental cinema), Blacktronica (helmed by Charlie Dark, and splicing live street poetry with broken beats), and indie music/film bash Little Stabs at Happiness (which the British Council later took to China, as a Brit culture export). These formed a counterpoint to the mainstream branding of London “superclubs” such as Fabric, Ministry of Sound and (the now defunct) Home—there was room for everything, and clubbing never felt predictable.

“Suddenly, clubbers were queuing around the gallery block on The Mall (with Buckingham Palace just down the road), the ICA’s ‘thoroughfare’ spaces came alive…”

“It was a radical gesture to do these events,” says Gaskin. Suddenly, clubbers were queuing around the gallery block on The Mall (with Buckingham Palace just down the road), the venue’s ‘thoroughfare’ spaces came alive, and ICA co-founder Herbert Read’s 1947 vision, “to create an adult playground”, was revived for new generations.

This highly visual, multi-disciplinary approach chimed broadly across nightlife scenes, as Swindells observes: “Clubbing became about creating this multi-sensory performance space. Any venue with a production budget is going to be doing that, whether it’s VJs, lazers or bouncy castles, or the confetti cannons and smoke machines you’d now see at Shoom or the Ibiza ‘superclubs’, or at big music festivals.”

Over the years, the aesthetic and atmosphere of club culture has increasingly inspired far-ranging visual art forms. Wolfgang Tillmans’s portraits of youth subcultures have whole-heartedly celebrated nightlife as “a fearless space”; Andreas Gursky’s vast photographs of rave parades reflect his personal love of techno music. Gursky’s recent Hayward Gallery retrospective also tied in with the launch of the Southbank Centre’s “new” clubbing venue, Concrete (within the Queen Elizabeth Hall foyer). Given that so many London music/dancefloor venues have been shut or faced threat in recent years (including Matter, the Pentagram-designed Greenwich club opened in 2008 by Fabric’s founders), the art/party space offers welcome fresh potential.

Elsewhere, clubbing themes surge through Mark Leckey’s mesmerizingly restless film Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999), created from decades of dancefloor “found footage”. There are Massimo Vitali’s stylized shots of Italian clubs in his Beach & Disco collection (1999), or Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist’s light installations, which Thornton argues “would look great in a nightclub chill-out room”. Dan Witz’s hyper-real club and gig paintings, collated in his series Mosh Pits, Raves & One Small Orgy (2016), reveal a fascinating depth of detail—though Witz’s contorted bodies seem frozen in time, and strangely cool to the touch. Jeremy Deller’s typically waggish approach to club culture has spanned different ages, whether it’s the dancehall exotica of Bom Bom’s Dream (2016), or the brass band cover versions of 1997’s Acid Brass (which didn’t really strike a chord with my young clubbing self—I recall watching Acid Brass’s live premiere, including a parping rendition of Voodoo Ray, and finding it stilted, stripped of the visceral passion that fuels club culture).

There’s an intimate relationship at play here, but it’s not always an assured one. “What I tend to be trying to do as a photographer is different to a lot of artists,” says Swindells. “I’m trying to record an experience in as attractive a way as possible; they foreground their own artistic response. Sometimes, there’s a self-consciousness that leaves me a bit cold.”

The most persuasive expressions, surely, are the ones where the artists themselves feel physically immersed in—rather than archly distanced from—the dance floor. For certain clubs, this has entailed producing their own take on art; special mention should go to late lamented “anti-superclub” 333, and its irreverent fanzine series Shoreditch Twat (incited by Neil Boorman). For certain visual artists, this has included embracing the role of club DJ or promoter. Lucienne Cole’s life-long love of music is reflected throughout her mixed-media artworks; she began DJing as an art student (her vinyl-only sets have been described as “a secular activity”), she hosted an after-hours club night during the first Liverpool Biennale (1999), and she currently co-runs a Northern soul club in London called Crawdaddy.

Memorably, Cole’s Whitworth Social Project (2008) united diverse communities communities in a Manchester gallery that had once been used for workers’ dances in the sixties—it also featured Haçienda DJ Dave Haslam spinning tunes alongside a local pensioner named Nora. “That project was for me about understanding how important dance is in bringing people together from all ages and walks of life, and living life to the full,” explains Cole. “A club is a situation where you hopefully leave all the crap at the door—enter another world. The act of whipping records on and off, of putting the needle down in the right place… it can be like a dance movement. It’s the best feeling ever, to be dancing all together… for that three minutes, nothing else matters.”

“A club is a situation where you hopefully leave all the crap at the door—enter another world”

Malmö-born and based artist Sandra Mujinga (currently exhibiting at UKS Oslo) sources online footage (including YouTube clips of Congolese wedding parties) to create the fantastically clubby atmospheres of her video works, such as When I Stopped Playing Hard To Get (2015), set to her own electronic soundtrack. Mujinga has adopted various DJ/producer monikers, including Charlie Orange (under which name she released a 2011 cassette homage to Janelle Monáe), Naee Roberts and 9Djinn.

“With DJing, as with visuals, I became interested in finding material that wasn’t necessarily that accessible,” says Mujinga. “DJing is also a way of creating a balance; when I play music—for instance, pop from across the African continent, I try to focus on female artists. Throughout my art practice, I try to work with representations of people, and things that are ‘missing’.”

Prem Sahib’s sculptures and installation works have summoned the modern clubs and gay nightlife spaces of his native London and Berlin in particular. In 2013 he staged a club night, Bump, to generate materials for his art exhibition, Night Flies. “I think it was something that evolved naturally because of the work I was making and experiences I was having, rather than a self-conscious decision to turn nightlife experiences into art if that makes sense,” explains Sahib. “There were remnants from Bump that became part of the exhibition such as the neon outside, or the carpet upstairs that got stained from its use. I also designed a bar with my boyfriend Xavi, which my dad and uncle then produced.

“In retrospect, what resonates most about that night was how much happened in a short space of time—all the conversations, the hookups, the amount of people having fun, or dramas even… Possibilities that don’t contest with what can happen when it’s a gallery. I think that is what interests me: the sense of possibility and freedom in an environment where everything is heightened. However, I’m also aware that nightlife can be easy to romanticize. Even in the nightclub itself, I think it’s possible for those ‘freedoms’ to be performed rather than lived.”

Nightlife continues to resonate through Sahib’s varied works. He’s currently working towards the Hayward Gallery-curated Art Night event, and designing a new maze-like sculpture in Vauxhall Park (inspired by the area’s meeting places and cruising grounds). Since 2011, he’s run the club event Anal House Meltdown with close friends George Henry Longly and Eddie Peake; the next event is at Bloc South in London’s Vauxhall tomorrow. “We often describe AHMD as a queer dance party that is all-inclusive,” says Sahib. “Increasingly, I’m valuing what it offers us as a space to get excited and be creative away from art world politics that don’t interest me.”

“It is easy to mythologize the dancefloor—but that fantasy state is undeniably the enduring lure of club culture”

As Sahib argues, it is easy to mythologize the dancefloor—but that fantasy state is undeniably the enduring lure of club culture, whether we’re losing ourselves in a theatrically designed festival environment like NY Downlow, or a techno set within a gallery foyer. “Even if the dancefloor is a ‘stage set’, it develops very quickly into a dynamic experience of its own,” says Swindells. “Maybe it’s about a wonderful ability to embrace illusion.” Club culture and art feel like fluctuating, intertwined forces—driven by a mutual urge to connect, to stimulate, to spur an irrepressible endorphin rush: a sensation that lingers even after the beats subside.

Read more about Night Fever: Designing Club Culture 1960-Today in issue 35

BUY ISSUE 35