“You think you wear the suit: the suit wears you.” AA Gill knew the power of good tailoring. He was rarely seen outside of a blazer. “It is woven magic, necromancy, the black art that hides in plain sight,” he wrote in the New Statesman four years ago. “No one knows or can say what the spell of the suit is, or how it works, but still it exudes its inoffensive wit.”

“It is as if, beneath the standard-issue black suit, man contains multitudes”

Gill was writing for Grayson Perry’s guest-edited Great White Male issue. His theory of the suit, in keeping with Perry’s notion of “Default Male”, argued that it elevated the wearer precisely by blending them in. “It’s not in the singular, but the collective,” he continued. “If there were only one in the world, it would be a mad thing, but its strength comes from the massed ranks, the united power, the union of flannel.”

I’d go further still. Suits are built as a support system, as much scaffolding as they are clothing. They are our armour against the world; hand-stitched exoskeletons that hold men together (and it is still mostly men). Suits button us in. Suits prop us up.

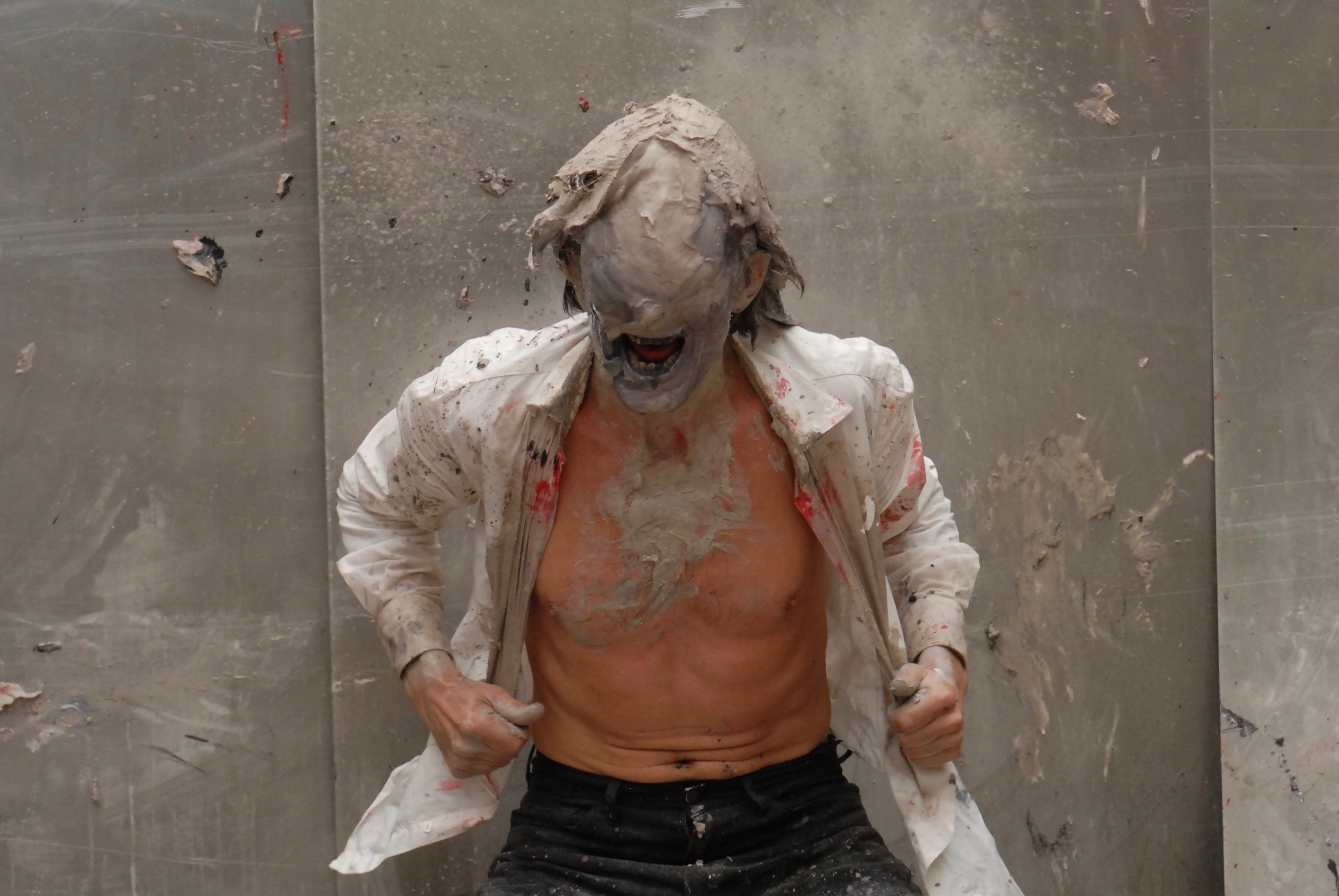

Olivier de Sagazan wears one in Transfiguration: plain black, single-breasted, with a starched white shirt beneath. He is “Default Male”, essentially, but over the course of forty-five minutes, he bursts out of that shell, sculpting and resculpting his head out of wet clay. Again and again, he seems to change shape—a monster, an animal, a shapeless thing. It is as if, beneath the standard-issue black suit, man contains multitudes. Transfiguration allows this “great white male” to find a superior spiritual shape.

It is, first and foremost, a ritual. De Sazagan circles the stage barefoot, pacing a bass beat out with his bare heels. He kneels over a square of untouched clay, pounds the floor rhythmically, breathes in and out, before clutching a clump of straw and setting it alight to send up a thick shroud of white smoke. As the embers flicker and pulsate, he lets his chants slide into mutters and clucks, as if he’s trying to leave language behind.

“At times, he tears into this flesh, punctures it, pinches it, twists it out of shape—all gestures of self-harm that, given the weight of wet clay, require effort and strength”

Suddenly, this figure sloshes a thin film of wet clay over his face, then another, and in an instant he’s masked—stony-faced. His silvery features resemble the Tin Man as if, in one gesture, he’s no longer fully human. All that has changed is his skin, yet he seems serene somehow, stiller, statuesque. He dips two fingers into a bowl of unctuous black paint, dots himself dead eyes and instantly becomes death. Slicing a line of bright red across his mouth, he changes again—monstrous, deformed, a skull with a maw.

This is the game of Transfiguration: de Sagazan continually rearranges himself, reshaping his features beyond recognition, beyond gender, even beyond humanity itself. The first shifts are simple: a bulbous nose, a lumpen cheek. The black dots slip to one side, then the next, like a living Picasso. His features start to melt; a Bacon painting made flesh. Between each pose, he wipes the slate clean, muttering something about “trying one time again,” then slipping further and further from his original form. He becomes deformed, elephantine, animal, alien, faceless.

There’s a violence in the process. It’s an attack on the self: a forceful act of self-mutilation, even self-annihilation. De Sagazan slams fistfuls of clay into his face, pushing his thumbs into his eye sockets or slicing sharp red slits across the “skin”. At times, he tears into this flesh, punctures it, pinches it, twists it out of shape—all gestures of self-harm that, given the weight of wet clay, require effort and strength. As the red paint runs into the gray, he can resemble a lump of raw flesh—muscle and bone. I thought of the trans artist Cassils, his female body honed into masculine shape, pounding and attacking a 2,000 lb lump of clay in Becoming an Image.

Yet for all the frenzy of Transfiguration, there’s precision too. Watching De Sagazan at work, you slowly clock his skill. He is, effectively, sculpting blind; his eyelids sealed shut by the clay. Working by touch, he feels his way through and each “face” is, inevitably, inexact as a result. Red mouths miss their mark. Black ink runs down his “cheeks”. The artist’s working on instinct, almost in a trance state and yet, amidst the shapeshifting blur, moments of stillness become finished sculptures—a bird with a beak supported by straw scaffold, a misshapen pig with a lumpen red snout. This is both improvisation and choreographed routine. Transfiguration is a ritual loss of control and, with it, of self.

“Having torn his clothes apart and remodelled his whole body, fashioning breasts and a mons pubis that quickly disintegrate, he ends sexless and ageless—a body that won’t be bound up by a suit”

Effectively, De Sagazan bursts out of his suit: he summons the primal instinct that still exists beneath modern man. I was reminded, variously, of Christian Bale’s facepeel in American Psycho and Martin Sheen’s mudbath in Apocalypse Now. In his suit, De Sagazan is both stockbroker and shaman: possibly divining good market luck, possibly obliterating himself for escape. “Disfigurement in art is a way to distance oneself from everyday life,” he writes in the programme, “and perhaps to better understand real life.”

It is an extraordinary visual spectacle: horrifying and hypnotic at the same time, no doubt thanks to that mix of violence and creation. Witty too, as different shapes and forms emerge out of clay. But there’s a real visceral charge. Microphones pick up his panting breath, and, as de Sagazan smothers himself in wet, viscous grey, you share the sensations—the slip and slide of the stuff, the cold surface, the suffocating weight. In both senses, Transfiguration gets under your skin.

In the end, De Sagazan becomes both human and not. Having torn his clothes apart and remodelled his whole body, fashioning breasts and a mons pubis that quickly disintegrate, he ends sexless and ageless—a body that won’t be bound up by a suit.

Elephant Rating: 🐘🐘🐘🐘 (4/5)