This feature originally appeared in Issue 31.

Born in 1967 in Miami, Florida, she “came out of the closet” when she was twenty, and her work epitomizes queerness, although, when asked about preferred terminology, Steiner opts for “Uranian”. “There is no definition of genders and/or sexual identities,” she explains. “We, as a species, are currently oppressed by societies built on indouchetrialized [sic] patriarchal structures, which command offers or denials of such things as ‘rights’, ‘freedoms’ and ‘equalities’. These structures are dependent on categorical, rigid formalizations of identity.”

Nevertheless, in a 2014 feature in Frieze, Steiner set out: “Queer is empowering, offensive, visible, academic, passé, over, urgent, overused, everything, irrelevant, empty, hurtful, hateful, possible, broad, narrow, nothing, futurity, hope, not enough, too much, just right. Queer are the things that bad things are not.” Reading or speaking to Steiner is like reading or hearing a form of political poetry—peppered with neologisms; full of to-the-point, could-be soundbites; trippy, in the sense of being taken somewhere you’ve never been taken before; but enlightening and motivational at the same time.

Steiner grew up as one of three girls, with a mother who owned an art gallery for thirty years, so she was immersed in the art world from a young age. She studied Communications and worked as a magazine photo editor for eleven years prior to following in her mother’s footsteps and becoming a fully integrated member of the art world herself. At the same time, however, she has always been involved in community activism and direct action, working at the HIV/AIDS service organization Whitman-Walker Clinic in Washington, DC after graduating from university, then joining Queer Nation and the Women’s Action Coalition in San Francisco, and eventually the Lesbian Avengers in New York. This involvement offers her a sense of feeling at home with people of shared gender and sexual identities. “Coming out of the reigning oppressive cultural paradigms of heteronormativity and heterosexism is never an easy or comfortable action,” she says. Her collaborative curatorial initiative Ridykeulous, founded with fellow artist Nicole Eisenman in 2005, accordingly mounts exhibitions and events primarily concerned with queer and feminist art, and uses humour to critique both the art world and culture at large. “We need Ridykeulous and Ridykeulous needs us,” says Steiner matter-of-factly when asked to elaborate. They were threatened with being sued the year of Ridykeulous’s launch by an artist who claimed the project was discriminating against bisexuals. The alleged crime was the omission of the plaintiff’s work in the zine they published, despite the fact that other bi-identified artists appeared in the project—a reminder that no matter how inclusive one seeks to be, someone will always feel left out.

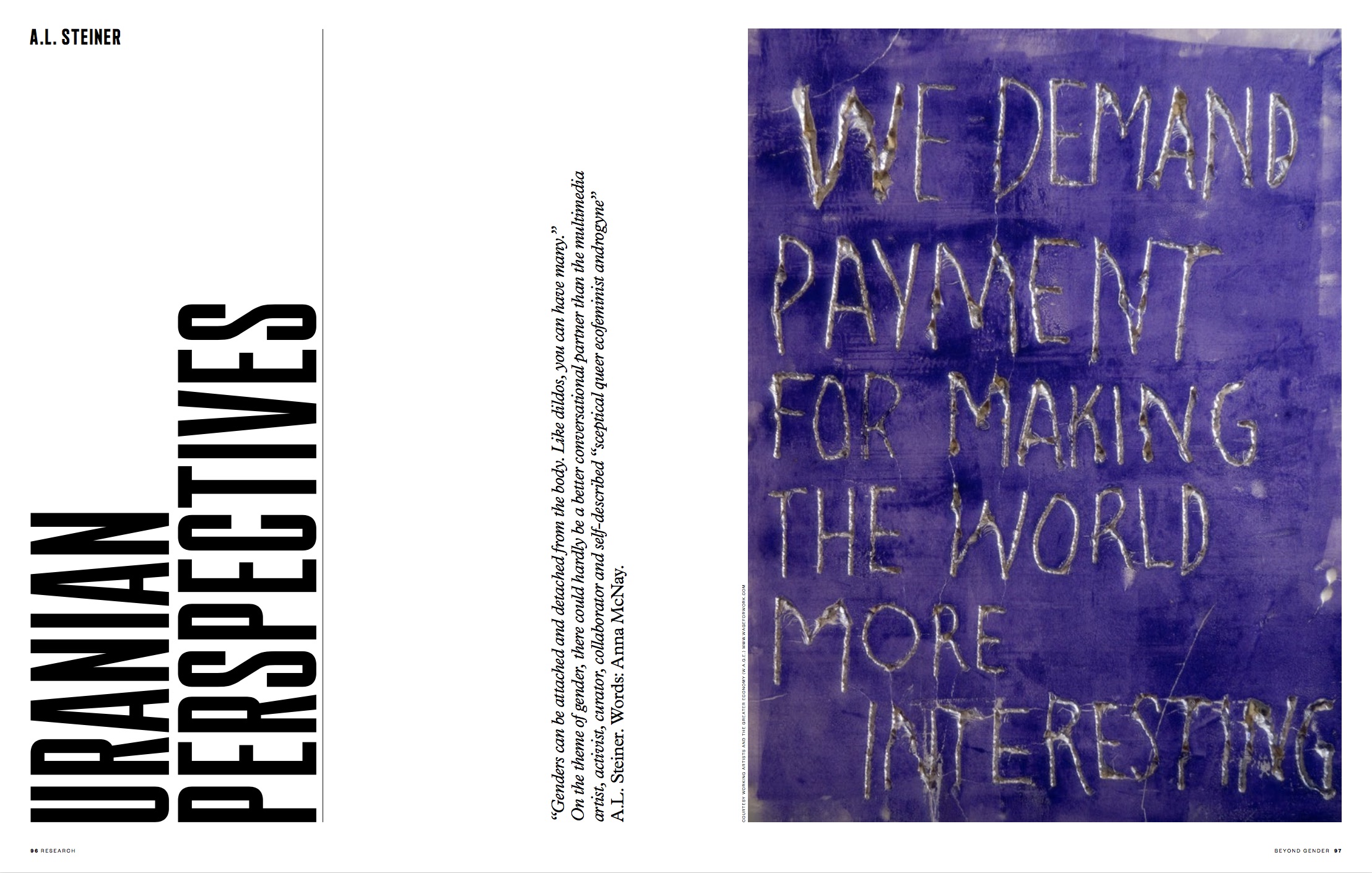

Seeking equality on another level, Steiner is also co-founder of Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.), a New York-based activist group advocating for financial compensation for the content that artists provide to nonprofit institutions. A survey the group carried out in 2010–11, gathering information about the economic experiences of visual and performing artists exhibiting in non-profit exhibition spaces and museums in New York City between 2005 and 2010, flagged, among other things, gender differences in the coverage of travel expenses, with 69 per cent of female respondents reporting that they did not have any travel expenses, compared to just 45 per cents of male respondents. Nevertheless, Steiner has spoken to the terms of “feminist art”, which she identifies as “languages and ideologies which establish lived practices running counter to competitive, omnicidal crapitalist [sic] patriarchy”. Asked whether she sees the current vogue for all-women or feminist exhibitions as ghettoizing and reinforcing inequality, she is clear that “the corporatocratic cultural institutions which uphold, reinforce, perpetuate and provide cover for the violence of the fiduciary nation-state reinforce inequality, not exhibition themes”. Equally, however, she maintains that “patriarchy is an ideology, not a gender. Any body can enact oppressive patriarchal psychological and structural oppression.” Perhaps it is for this reason that Steiner so strongly holds that everything we do iso—or ought to be—collaborative. “The belief that there’s anything that’s not collaborative is the root of our problems.”

The blurry distinction between love and hate, collaboration and treachery, is explored in the short film work You Will Never Be a Woman. You Must Live the Rest of Your Days Entirely as a Man and You Will Only Grow More Masculine with Every Passing Year. There Is No Way Out (2008), made together with Zackary Drucker, Van Barnes and Mariah Garnett. Two trans-identified women share moments of love, insult and masochism, preparing each other for a larger, more dangerous culture of intolerance and violence, and occupying multiple roles. All gender, according to Steiner, is a drag. “Genders can be attached and detached from the body. Like dildos, you can have many.” In her multimedia artworks, she often juxtaposes images, bringing them together in a collage form, to create and offer multiple readings. “I wholeheartedly believe in the truths of multiplicity,” she says, “and fully reject the false-flag operation of individualism.”

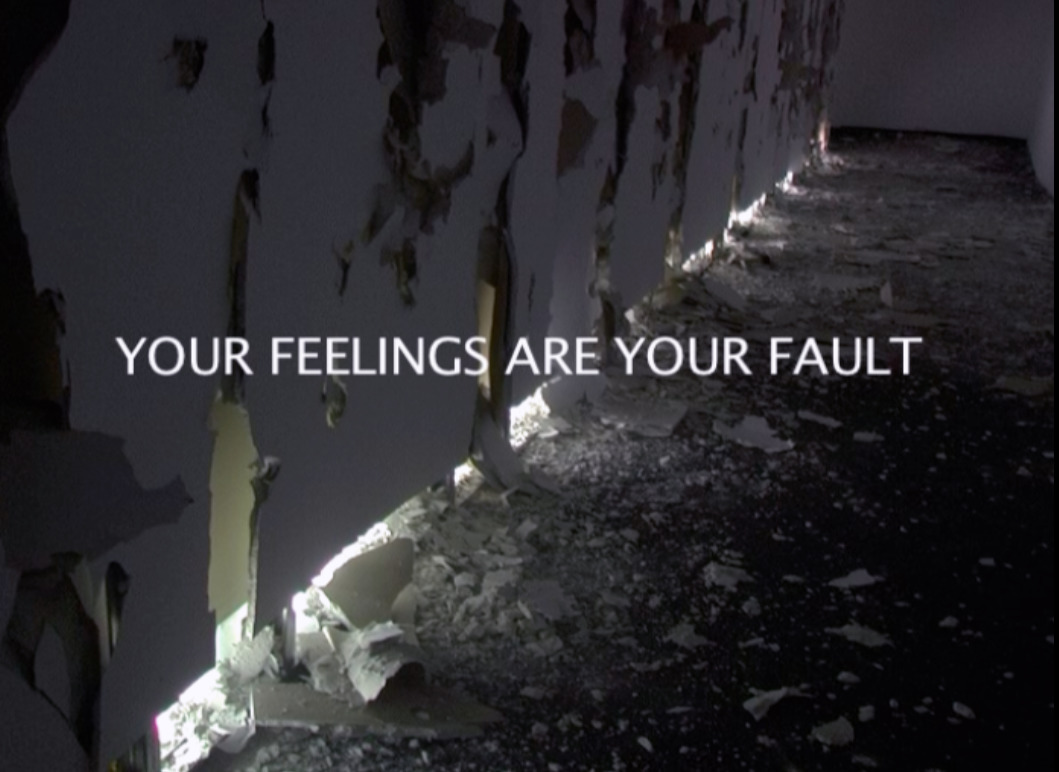

Steiner’s work sometimes seems to seethe with anger—she was once asked by a reporter if she was an angry feminist—and she has commented before that “if you’re not angry, you’re a crazy person… Whether ecstatic, pleasurable, or angry, there is so much that I am dealing with in the space, the mood, the show, the curator, that factor into how a piece comes together. I use the pictures to mine my subconscious state.” Now she adds: “Some humans are angry that there’s not enough hate in their world to perpetuate their anger; others are angered by how much pain humans create in this world. I fall into the latter category.” Shock, on the other hand, she sees not as an effect of the artist, or of the audience, but “a result of what is deemed culturally transgressive at any given moment in time. What we feel to be shocking is a temporal affect, a psychic experience of time travel.” She has called this the “Mapplethorpe effect”, pointing out that the shock value of an artwork doesn’t mean that the artist is setting out to shock people, although they may acknowledge the work is culturally transgressive. The public’s shock originates from the viewer’s position, as succinctly described in the title of Steiner’s 2008 video, Your Feelings Are Your Fault.

Steiner—perhaps controversially for an artist seen as “queer” and “feminist”—considers Gustave Courbet’s Origin of the World (1866) an attempt to revere and embody, rather than to objectify. “I believe gaze is determined by cultural signifiers that define power relationships,” she explains. ‘Understanding W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory of double consciousness, or reading Monique Wittig’s The Lesbian Body, can help snap one out of the de rigueur psychosis of the heterosexist, white-identified supremacist patriarchal haze.” Steiner’s projects and collaborations are described as “celebratory efforts in dismantling notions of normativity and the sources of constructed truths”. In her photographic work, women are seen naked, perhaps as sexualized and eroticized by some. “Nakedness, nudity, the Nude, body parts, flesh and flesh eaters populate this exhibition,” wrote the gallerist Pascal Spengemann of Steiner’s 2009 exhibition in his now-defunct Chelsea (NY) space. “Some flaunting and others demure. Transparency, honesty, and forthrightness are all demonstrated here, but perhaps with a false promise, a come-on, a fantasy, a mirage.” While clearly intending both subversion and irony, Steiner still maintains: “Making anything is an act of objectification.” In terms of viewing and interpreting her work: “50 per cent is me, 50 per cent is you.” The viewer’s physicality is important to her in relation to viewing: “I don’t want a sensation of overwhelmed, I want there to be a sensation of infinity. That this isn’t finished, it’s never-ending.”

In Puppies & Babies, an exhibition for 3001 Gallery, Los Angeles, in 2012, Steiner brought together inflated images of “pets, pregnancy and children”, collaging the abjection of childbirth with the soppiness of puppy love. In a conversation with Steiner for BOMB magazine, the American writer Maggie Nelson says: “This is what I like so much about your work. You acknowledge the fear that you might be pushing toward a place that you aren’t sure will be a good one to go to—in the case of Puppies & Babies, into the sentimental, or banal, or clichéd, or whatever. You push on anyway, you respect your impulses, until you find/make something completely worthwhile.” Steiner responds by acknowledging her investigation of “the unsustainability of the binary—normative on one hand, and transgressive on the other”. And certainly much of her work is an open investigation, as, indeed, are her answers to me:

“Does the body represent or define identity?”

“Yes.”

“Or is identity beyond the body?”

“Yes.”

“What about the collective/community body?”

“What about it?”

Perhaps this is the 50 per cent that is left for the viewer to decide.

Buy Issue 31.