Zoë Buckman was born and raised in Hackney, London but for the best part of the last decade has lived in New York, where she is now raising her daughter. Recently Buckman returned to London to present an extensive new body of work titled NOMI, shown at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery’s online viewing room. The work really began two years ago when Buckman embarked on a deep inward journey, undergoing psychotherapy as well as travelling to India with her daughter, where she deepened her spiritual practice.

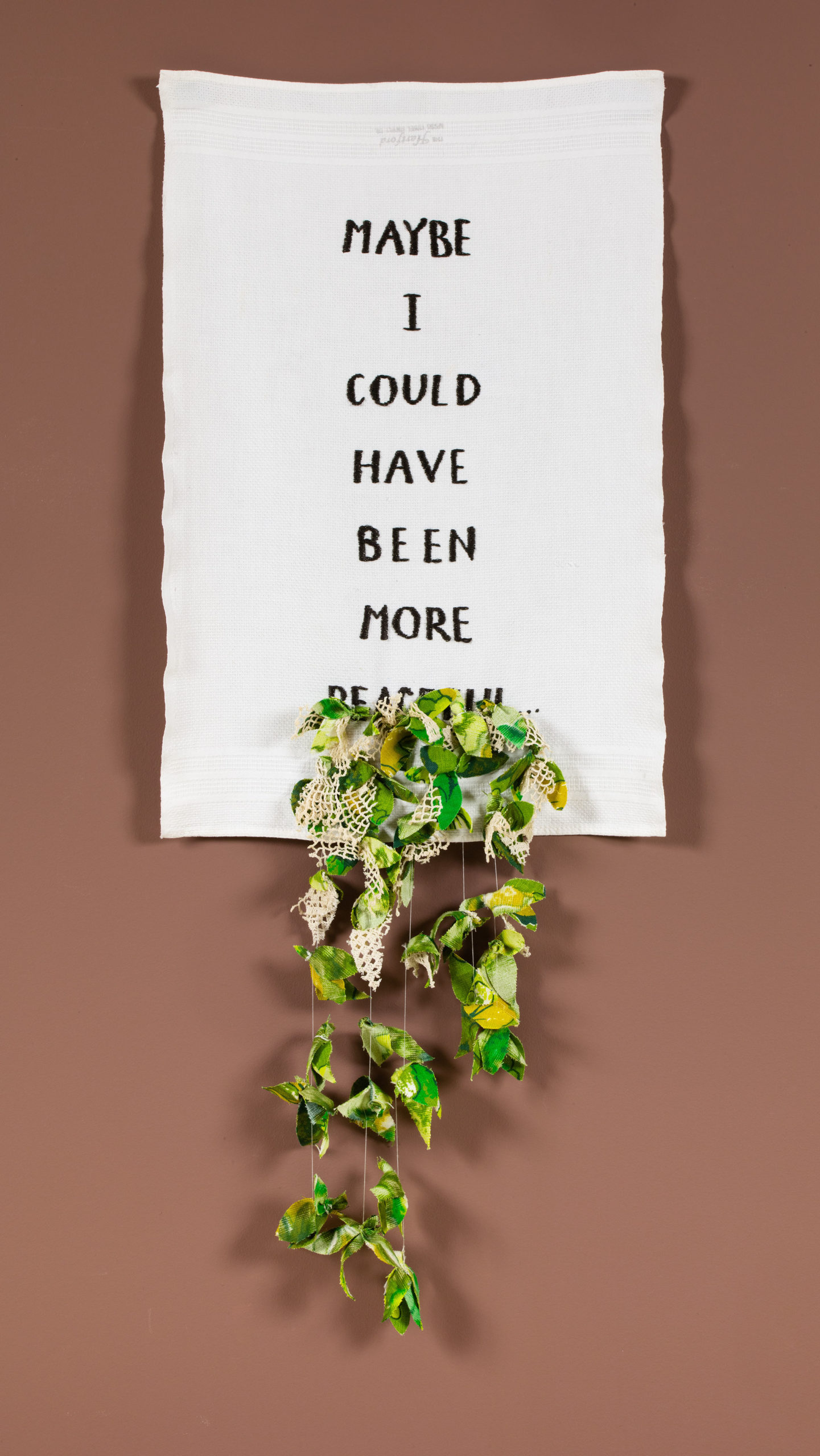

Nomi is conceived as the artist’s alter ego, depicted as a serpent shedding its skin; ideas about rebirth and healing are replete in these works, which originated in traumatic experiences that Buckman had previously suppressed or avoided in her art. Each of these new works touches on dyadic exchanges, between things we perceive to be inherently opposed: grief and joy, violence and softness, praying and partying, masculine and feminine, text and image.

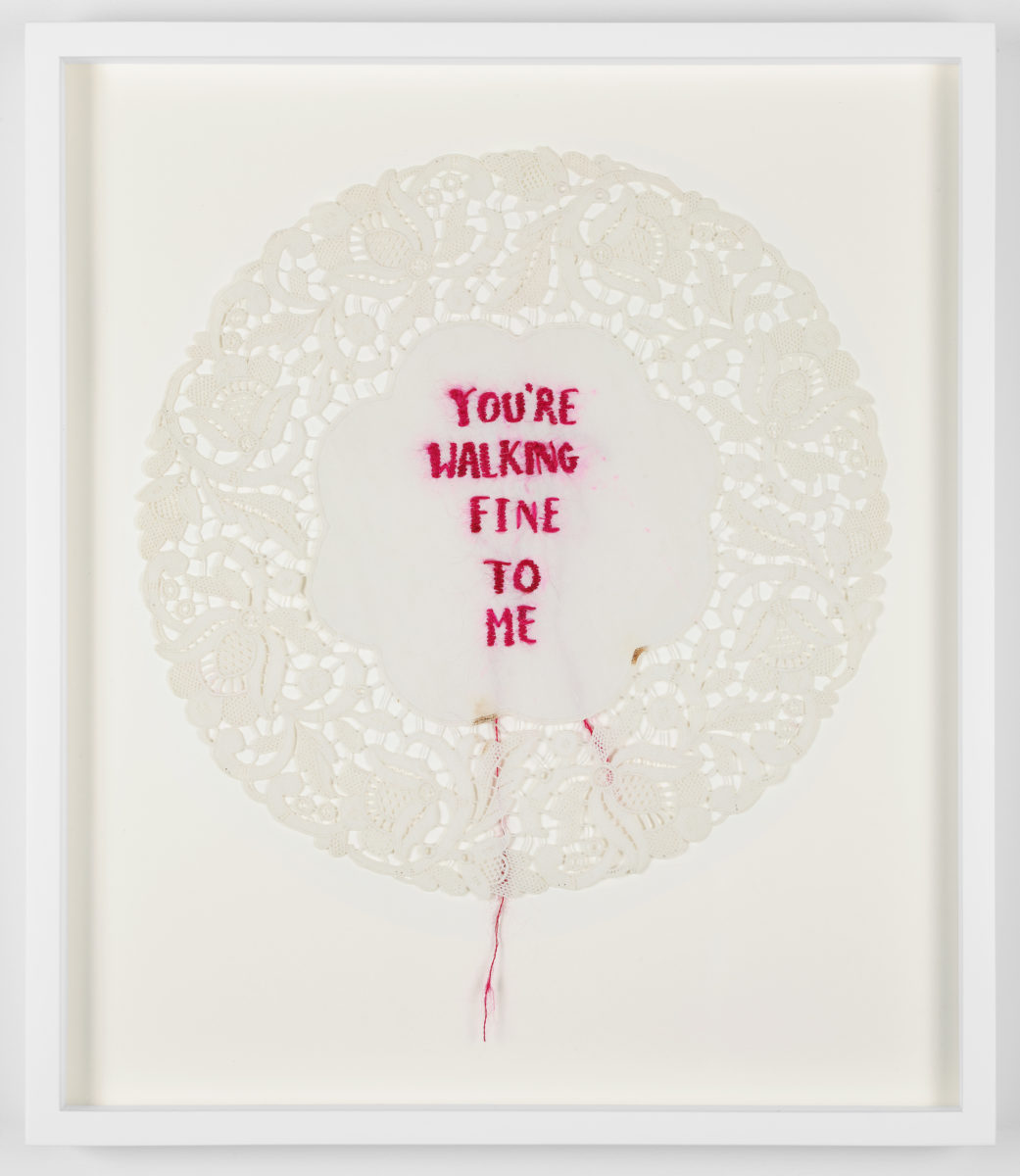

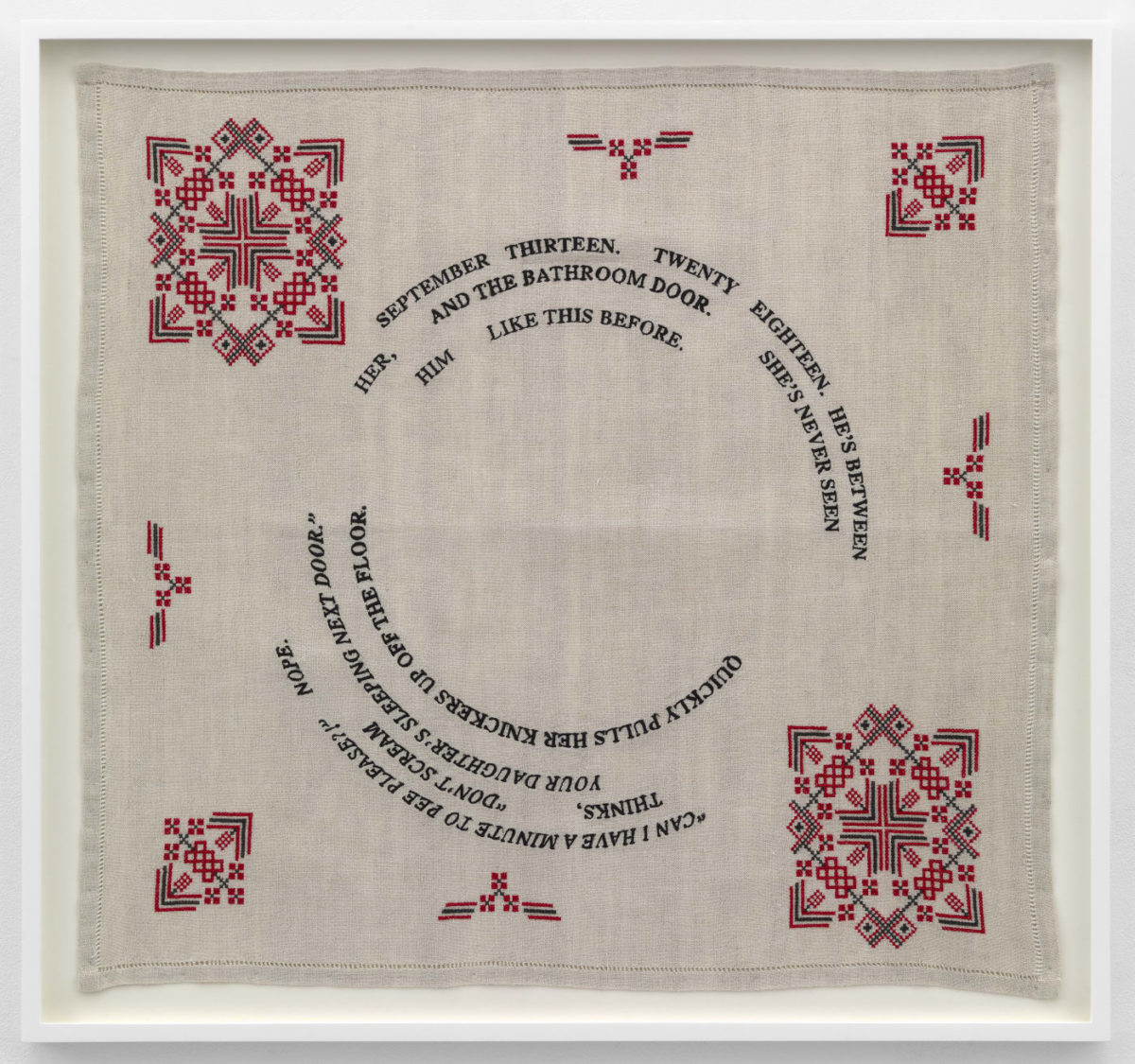

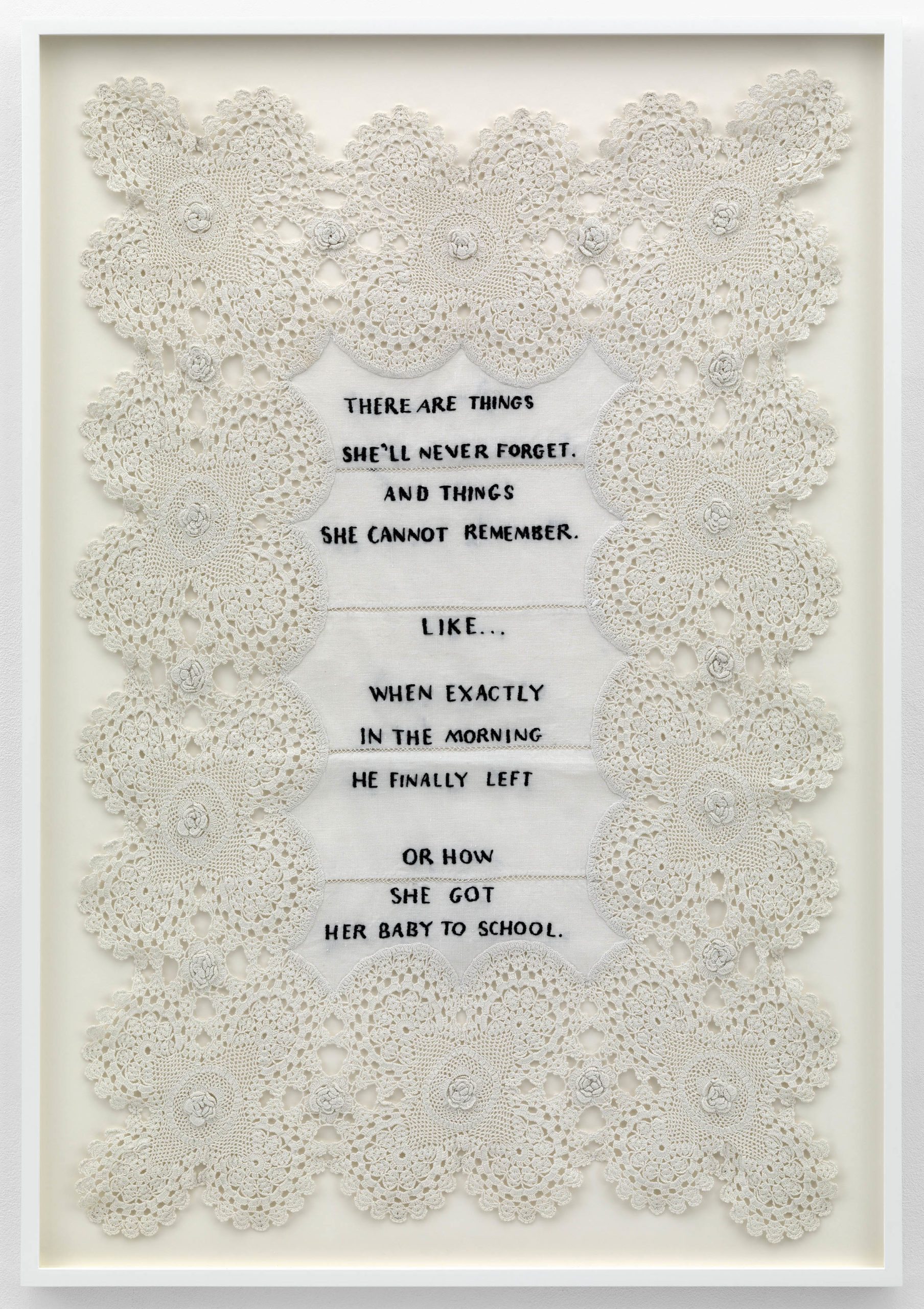

In sensual, intricate and intimate works that make use of vintage household textiles, embroidery, photography, ink and text, Buckman finds a new visual language for the female experience, something like the radical circular writing proposed by Hélène Cixous in the 1970s: “Your body is yours, take it”, the writer urged. This is exactly what Buckman does.

Can you tell me more about the role of text in your work: both within your works as embroidery, but also in your titles. How and why did words become an important element in your practice? I’m reminded sometimes of Tracey Emin in the way you give these glimpses that are sometimes so devastating and catch the viewer off guard.

An appreciation of language and the power of words was very much part of my upbringing. My mother was a writer and acting coach teaching at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, so our living room was often full of students spouting Shakespeare monologues. This was Hackney in the 1980s and 90s and the predominant culture revolved around hip hop and slang. I learned to see linguistic richness in all types of spoken or written art, whether that was from going to rap battles in Camden or asking my mum to help me with my homework on the Romantic poet John Keats.

I look at text in my work as an opportunity to expand the viewer’s experience. Sometimes the language is ugly but the execution is warm or inviting. Language can give humour to something painful, or can remind one of a whisper or something said in passing that is actually weighty or sinister. I’m really glad that titles for works exist as a concept because, as you’ve pointed out, it gives me yet another layer in which I can add to or play with meaning.

“I started to do a type of therapy that allows a stuck traumatic memory from the middle of the brain to move and metabolise”

Doilies feature a lot in this body of work, which are suggestive for many people of a very particular time and place; are very gendered and rooted in the domestic. What is the significance of them to you and why did you want to use them in your work?

I started to use domestic textiles like doilies and table runners back in 2018 when I was working on my previous series Heavy Rag, and for the exact reasons you mention. It was a time when I was examining the home, and the experience of women in the home as a place of both trauma and nourishment. This series continues to examine these ideas but expands upon them, and collected more doilies for Nomi specifically for their round and almost brain-like motifs.

In 2019 I started to do a type of therapy for trauma and grief called EMDR, which works to trigger the left and right cortexes of the brain in sequence, allowing a stuck traumatic memory from the middle of the brain to move and metabolise. I found this fascinating and began to place two round, often lacy doilies next to each other and let wet ink bleed from one to the next, or use thick mohair thread and knit them together tightly. Some of the textiles belonged to my mum or my grandmothers, but most are sourced from vintage and antique shops.

- Left: Through the Cradle, 2020. Centre: & I Can Fall Into Your Creases, 2020. Right: Time Turned Chains Into Rust, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery

This work was made in 2020 and addresses grief and trauma. You’ve also spoken quite openly about your experiences with violence. Many of these works are abstract in the way they address those experiences but they’re very bodily at the same time. They’re materially fragile; they bleed; they’re stained; they’re dripping. How much were you thinking about bodies when you were making these works?

This is the first time I’ve depicted the body in my work. It’s something that I’ve avoided until now, not wanting to contribute to the over-objectification of the female form within art. So I took it seriously: how I would use the body, how they would take up space and be joyful empowered figures, as well as authentic depictions of us. They are all taken from photographs I have. There are a lot of images of me and my girlfriends dancing. I’m struck by the strength of the women I surround myself with and also the common thread of the joyful way they celebrate their bodies despite all they and we have experienced.

I also used photos taken of me while I was praying in India. I’ll create these new spaces where ravers and devotees co-exist; where a woman’s body is twerking plus ceremonially offering at a holy river. These new forms bring together what we are told should be binary. The forms are unfinished, which is also a first for me! They are in transition; they can’t be held back; they’re growing or becoming undone; threads are loose and the ink bleeds unpredictably because I cannot control the art any more than we cannot be controlled and limited ourselves. There exists, I hope, a lot of freedom and joy in the ways in which I’m using the body for this series.

Boxing gloves feature in your work and are something you are known for. Where did that come from, and why the gloves?

I started boxing in 2015 in the run-up to the election in the United States and when I was beginning to separate from my marriage. I was also starting to get some traction in the art world (which is such a male-dominated industry) but I was not yet good at owning my space or feeling like I had a right to it, let alone taking up space from someone else. Boxing put me back in touch with my inner fighter. It was natural that the gloves, these weapons clad in the softest leather that speak to masculinity and aggression, as well as protection and defence, should make their way into the work.

Sometimes there are clusters of many gloves, hung like a body on a chain. At other times I’m using two gloves in prayer, or one balanced on the other to suggest that tension of not knowing if or when it will slip away, or whether you’re holding another person up or pulling them down.

“They are in transition; they can’t be held back; they’re growing or becoming undone; threads are loose and the ink bleeds unpredictably“

How much did your time in India influence this body of work and your way of thinking?

My trip to India was incredibly formative for me personally, and for this work. It was my fifth time there, but the only time I had taken my daughter along with me. Together we offered back my mother’s ashes to the Himalayan Ganges and bathed in the freezing water. It was a rebirth, and it was the first day I’d had since losing her that I didn’t want to end.

I also began to develop my relationship with deity worship out there. This show is called Nomi because that’s the name I gave to the wild, shadow aspect of my psyche some years ago in Jungian analysis. Perhaps I find it easier to connect with an alter ego or persona when examining my psyche because I grew up around so much theatre! In any case, with Hindu traditions there are many characters for the divine, to suit a particular devotee’s temperament or their soul’s calling. A person can feel pulled to a particular God and worship only them. The important thing to acknowledge is that all deities are part of the same divine energy, just with different vibes or personalities, as it were.

Once I accepted that I could discern which deities most resonate with me. So I began to form deeper connections to the idea of Radha: the one who loves the most, Durga: who comes in peace but will slay if she has to; Mother Ganga who is pure divine feminine energy in the form of water; and Krishna who is playful and eager for and appreciative of the love of the devotee. This work is very much about celebrating the complexities of women, the fact that we can be sexual and pious, fighters and worshippers, so in some of these works you can find Kali the Goddess of destruction as well as Radha. Because we all have both, plus everything in between, within us at all times.