The Israeli artist Guy Ben-Ner, who has spent time in New York but currently lives and works between Berlin and Tel Aviv, has made some twenty short films over the past three decades. He became known for appearing with his family, making work which could be seen as child-compatible entertainment, as well as playing into deeper concerns by equating the dramas of a family with the dramas of the world. He began with his four year-old daughter in 1999. “My studio practice was reduced to nothing,” he says, “so I started working with her at home. Video was an immediate tool that could involve her actively in my practice. Besides, by that time I was interested in telling stories, and a time-based medium seemed best for that purpose.”

Following his divorce in 2008, Ben-Ner’s casting has become more disparate, though his children returned for Soundtrack (2013)—with the addition of a new daughter from his current relationship. Rather than merely reflecting life, Ben-Ner has found that art can change it. “Often I build things or perform actions in my films which later get realized in life,” he says, “I got divorced in film half a year before I did in reality. Maybe it’s the wearing of masks that helps you get to the truth of things more easily. Truth comes in the guise of fiction.”

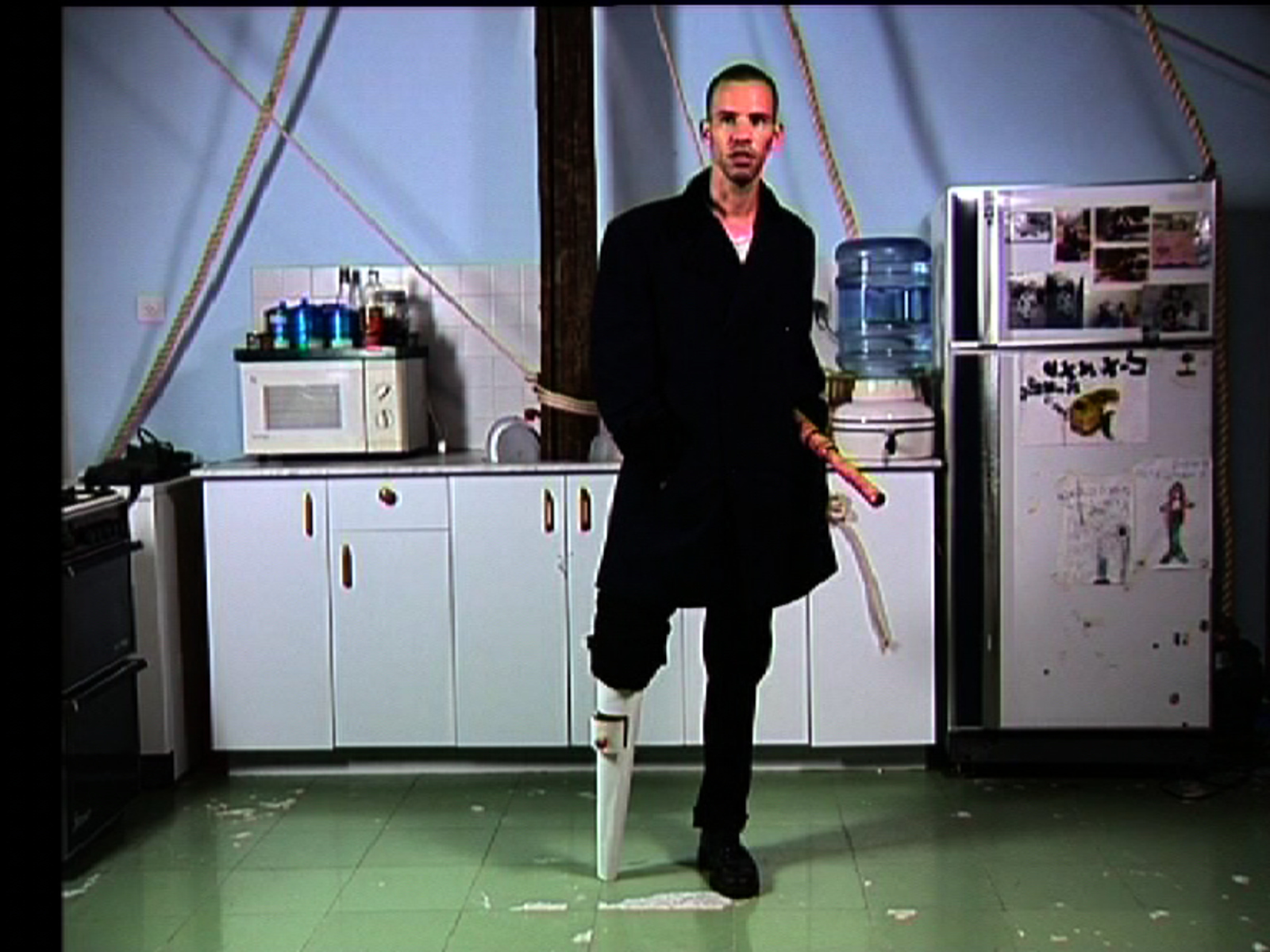

- Guy Ben-Ner, still from Soundtrack, 2013, © Guy Ben-Ner. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London, andSommer Contemporary, Tel Aviv

What remains constant is that the films are accessible and funny; they make a virtue of being low-tech and exposing how they are made; the personal is bridge to political and economic issues; and the conventions and typical content of various genres are used as a backdrop to exploit and undermine—home videos, shipwreck survivor stories, prison breaks, family sit-coms, instructional films, nature documentaries. If that gives the impression that these are amateur versions of the professional product, that’s not quite the point. As Ben-Ner says, “I am very professional in what I do. My artistic decisions are ideological decisions. You will not see me making a feature film with professional actors and a lot of money: it seems really boring to me.”

Ben-Ner became known through the absurdly home-baked re-enactments of famous literature, such as Berkeley’s Island (1999), which relocated Robinson Crusoe to the kitchen, and Moby Dick (2000). However, Elia (2003) is a charming self-standing tale and Stealing Beauty (2007) is the acme of his earlier family films. Foreign Names (2012), Soundtrack (2013) and Escape Artists (2016) are three more recent films which examine the state of the world more explicitly than before, though such content is always handled with a lightness which is a long way from didacticism.

“Ben-Ner’s films revolve around families, which he depicts with refreshing balance”

Ben-Ner’s then-eight-year-old daughter Elia gives her name to a story which might now be read as a parallel for the human migration on which Ben-Ner has recently focused. The film follows the journeying of a family of ostriches, with Ben-Ner as the father-leader, and then-wife Nava as the protective mother who brings up the rear. Elia wanders off and loses her way in the dark forest where she has to spend the night before being rescued in the morning. The whole family is decked out in gloriously silly costumes which require them to walk backwards to mimic the ostrich’s gait. The voiceover spoofs the way natural history documentaries typically anthropomorphize animal action—though with the neat twist that these birds are, after all, human.

What appeals to Ben-Ner about using such established templates? “Different genres are interesting,” he says, “because they are not empty vessels into which you pour content, but are always already ideologically charged. Nature documentaries say something about what is considered natural in our culture, family sitcoms hide economic and financial structures—and reveal them only in the commercial break.”

In Stealing Beauty, Ben-Ner, wife and children install themselves in a succession of IKEA model homes, there to live among the price tags and customers. Every now and again, they get thrown out. Activities include washing up (without plates), going to bed and taking a shower (where it seems the artist is caught in the wasted labour of masturbating). Mostly, though, they’re sitting around discussing Engels on property, as triggered by the son being sent home from school for stealing—cue his father’s lectures on right and wrong, which veer off uncomfortably into children as “good business for the future” and trigger the awkward question: “Is Mum private property?” Stealing Beauty is deliciously entertaining yet grapples with serious issues of economics and morality, and might also be seen to presage Ben-Ner’s concern with homelessness.

“Stealing Beauty is deliciously entertaining yet grapples with serious issues of economics and morality”

Perhaps it’s relevant, too, that the customer must put together any furniture bought in IKEA, for Ben-Ner is often seen constructing or dismantling objects. Treehouse Kit (2005), for example, sees him convert a large wooden tree created from recombined, generic furniture back into a home of sorts. He relates such activities to “a very particular kind of narrative, one that is predetermined, like manuals that come with a bed you have to build yourself, that you supposedly cannot get wrong. The performative aspect is also a way to try to build narratives out of the non-narrative background of visual arts—because in art school you were taught about the deconstruction of narratives, but nobody told you how to construct one.”

For Foreign Names, Ben-Ner visited 100-odd Israeli espresso bar locations in which customer collection has been introduced, left a fake name in English that would be called out at the counter when his coffee was ready, then edited all the videotaped snippets to create an “ode” lamenting the disappearance of waiters. As in IKEA, the corporate look of the Aroma chain is enough to provide an illusion of continuity. In the video, the staff seem to complain publicly in faux Marxist style that, for example, that “our waiter comrades lose jobs to the mic while the owner gains money and the artist steals its sound”. There is the odd giggle as announcements are made, and the server, given the last two words of “the rights of the worker are an empty phrase”, checks with Ben-Ner as he walks up to grab his drink “You’re ‘Empty Phrase’?” The corporate chain is made to skewer itself, and its staff, perhaps, are made to voice what they would not have dared.

Soundtrack also uses a brilliant formal device. The track in question is minutes twenty-two to thirty-three of Stephen Spielberg’s adaptation of HG Wells’s War of the Worlds. A stream of gags enables Ben-Ner to match its sounds and dialogue to a home movie: the blender stands in for a plane taking off, and there’s plenty of smashing and burning as the artist-father struggles to cook. The kitchen, incidentally, often acts as the set for Ben-Ner’s films. As he explains, “It’s the public sphere in the private home. It’s the town-square of the house. It’s where work needs and pleasures meet.”

And it’s there that a laptop turns out to show the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: domestic battles don’t just imitate the film, but also stand in for wider politics—not so much the effect on the family of Hamas rockets (almost all exploded mid-air by the “Iron Dome” defences) as the disproportionate impact of Israeli attacks on Palestinians. And where should the family be in all this? Retreating to focus inwardly, as in Spielberg’s film, or actively standing up for what is right?

Either way, Ben-Ner’s films revolve around families, which he depicts with refreshing balance. I suggest it can’t be all bad. “It can’t be all good either,” he replies. But is the family, I wonder, a historical construct which may well lose its grip some day? “It’s a construct in any case,” he says, “and can be reconstructed in different ways. I do believe it is an economic construction related to the way we want to hold on to private property, just as the nation state is such a construction. Even the way we are jealous for our loved ones indicates the property relations we are all contaminated by.”

Ben-Ner’s most recent film, Escape Artists, shows him giving classes in film theory to the occupants of a refugee detention centre. He demonstrates, through various clips—principally from the silent 1922 account of the Inuit people Nanook of the North—how the presence of a camera and the actions of the director lead the audience into what may well be false assumptions. For example, Nanook is shown holding up a fish he has caught as if he is a recreational fisher—because, we may deduce, he has been asked to do so. As Ben-Ner discusses with the refugees what tricks have been used, he sets up questions for us. How have our views of refugees, and their views of the nations to which they hope to emigrate, been shaped by media distortion? What tropes has Ben-Ner employed in making this film, and can we ever hope to see beyond them?