As the ubiquitous symbol of romantic love, the heart is a motif almost universally recognized, despite the fact that it has practically nothing in common with the four-chambered power muscle that keeps us alive. At this time of year, the emblem is central to the saccharine Valentine’s Day marketing that bombards us online and IRL, and as the “like” mentality continues to grow, the heart has become synonymous with myriad forms of affirmative communication.

For example, in 2015, when the Internet when mad for a few moments due to Twitter’s decision to replace its star button with a heart, the platform released a tweet announcing that the symbol could mean any of the following: yes/ congrats/ LOL/ adorbs/ stay strong/ wow/ hugs/ aww/ high five. Likewise, a quick scroll through the iPhone

emoji keyboard brings up no less than thirty possible variants to choose from. In this day and age, it would seem that the simple heart can say an awful lot.

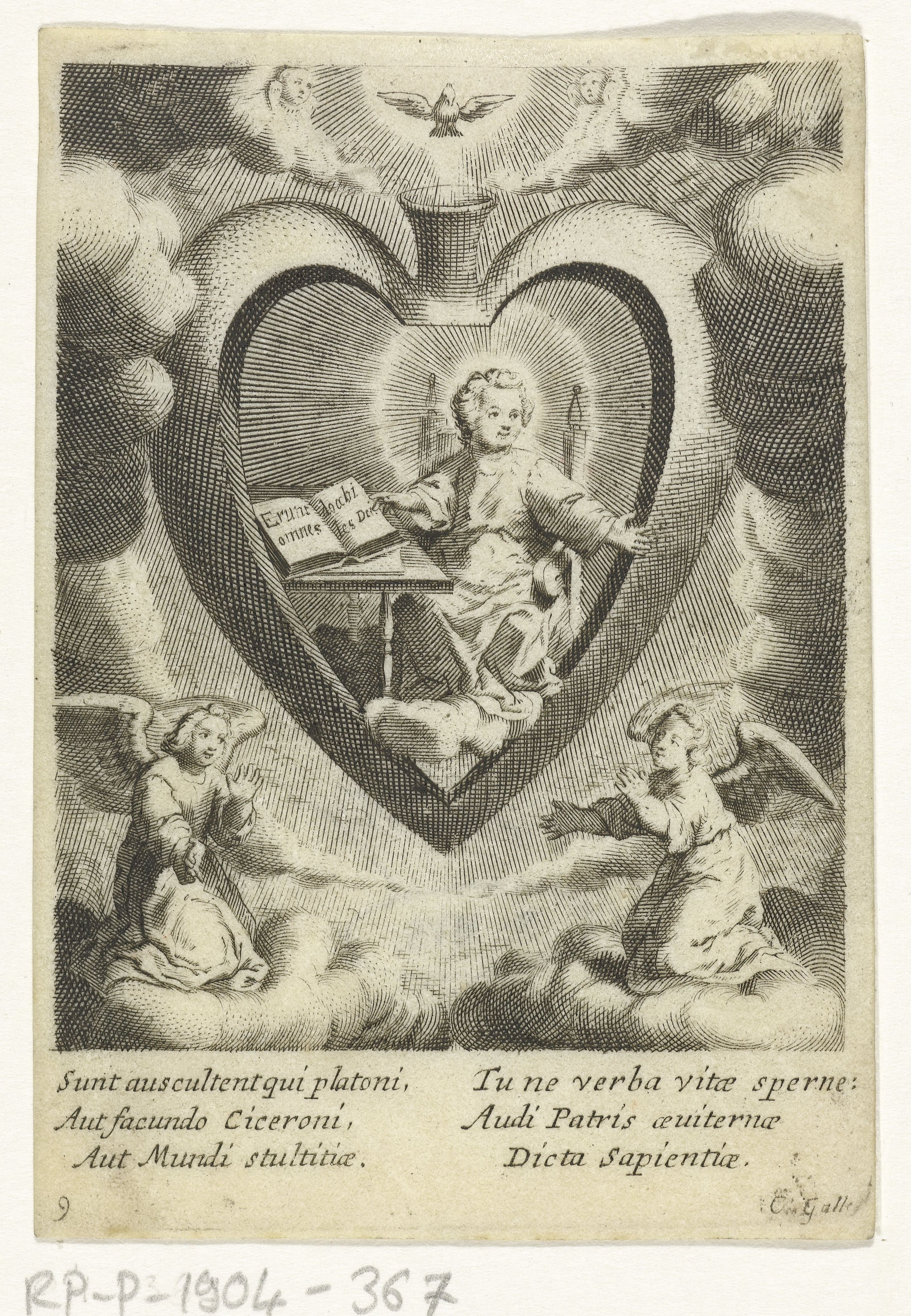

Cornelis Galle (II), Christ Child with Book in Heart, 1638-78

Considering this icon is so readily used and understood, very little is known about its origins. Accounts point to a plant with heart-shaped leaves that was hailed by the Romans for its contraceptive powers, thus linking the shape with amorous activities. Other sources look to mediaeval anatomical drawings that attempted to replicate the actual organ, at a time when it supposedly controlled emotion and pleasure.

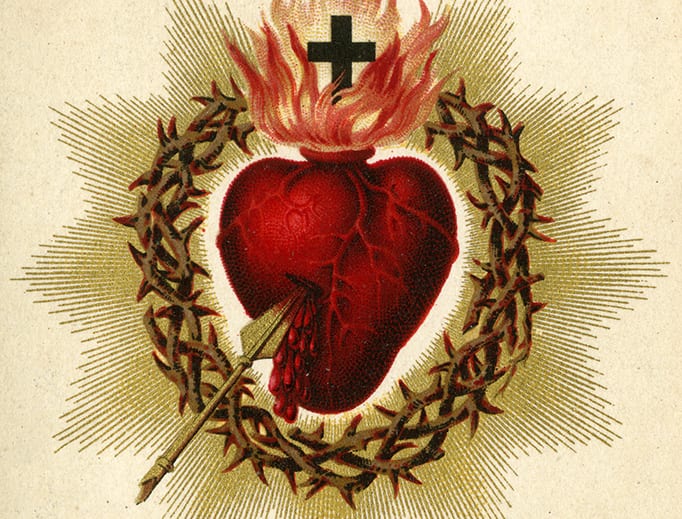

The Sacred Heart is also an image central to the Catholic faith, but it wasn’t popularized until the seventeenth century. As for Valentine’s cards themselves, although the tradition of sending a missive on 14 February dates back to the Middle Ages, we have the Victorian spirit of commerce to thank for the invention of specially-designed salutations covered in cherubs, hearts and cuddly animals.

Nowadays artists use the heart to subvert as much as reinforce stereotypes. Jim Dine, who was aligned with but never truly part of the Pop Art movement, has long-used the symbol as a base from which to explore texture, form, colour and material, as opposed to focusing on any grander meaning. Mari Katayama, on the other hand, considers a “heart that is all cut and broken is more beautiful”. Her photograph Cannot Turn the Clock Back #009 features a textile sculpture that seems to feature all the trappings of an overly-adorned locket, until you realise that the heart is covered in sinister embroidered fingers that allude to the artist’s physical disabilities.

Video artists Rachel Maclean and Wong Ping celebrate the superficial and trivial interpretations of the motif, as well as its ever-increasing colloquial usage. For Maclean, hearts supplement the unsettling, sickly sweet dystopian universe created in Feed Me, where the word also becomes a substitute for “love”. This linguistic evolution that can be traced back to Milton Glaser’s famous tourism slogan developed for New York City in the 1970s. The same language is used in Maclean’s print series I Heart Scotland, where the symbol—complete with Saltire—appears among her depictions of Scottish mythology.

In his video piece Doggy Love, Wong Ping recalls his classmates’ own speculations on the origins of the heart, suggesting a similarity with the head of a penis, or a woman’s buttocks. His own surreal experiences of life and love are chronicled by a preoccupation with “the shape of a red heart”, which he finally discovers you can only truly experience “when you are lying next to the one you really love”.

This sentimental image is supplemented by a heart-emoji of the artist’s own making, which spins across the screen like a runaway video game character. The effect is something sublimely ridiculous, but it does present a full view of the many ways we interpret this pervasive symbol. It can account for a passionate proclamation of unending devotion, or just another double-tap as we scroll through our day.