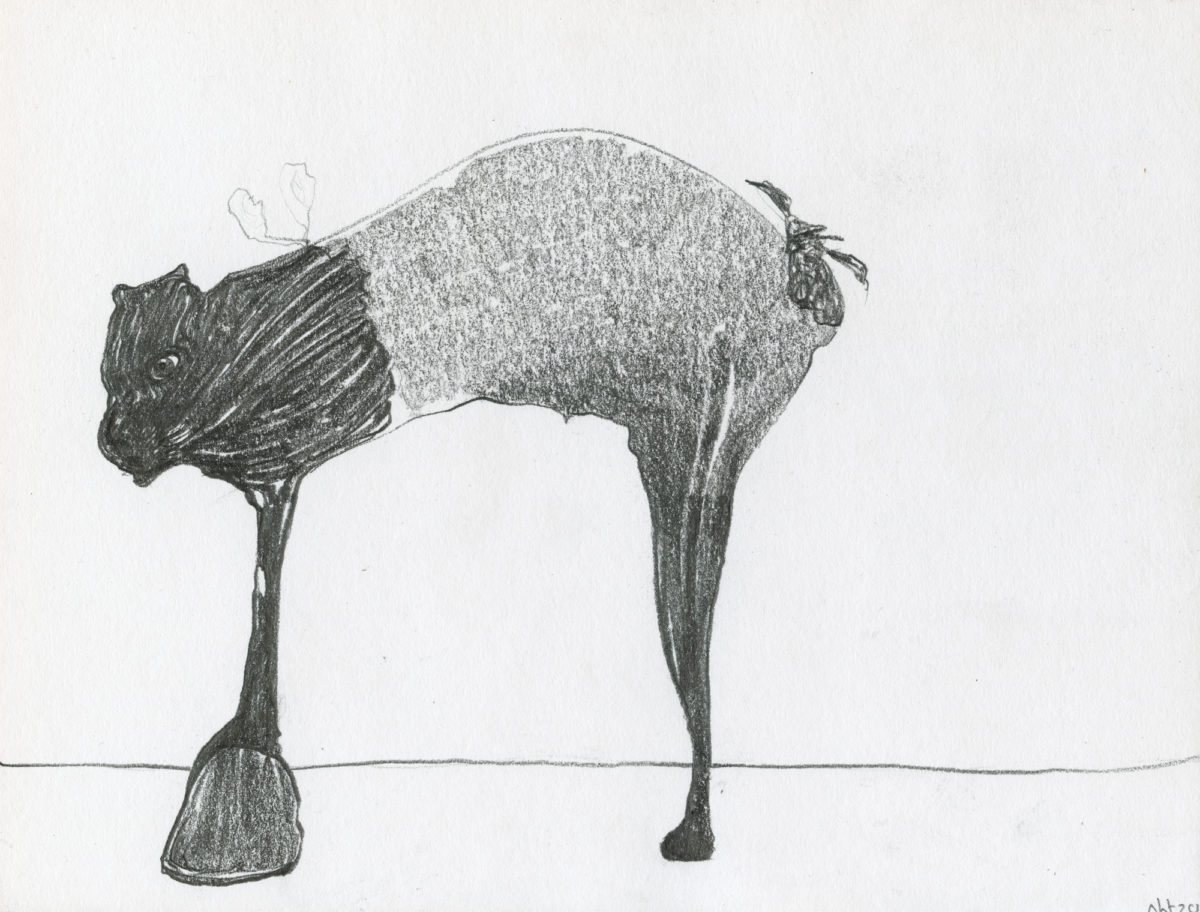

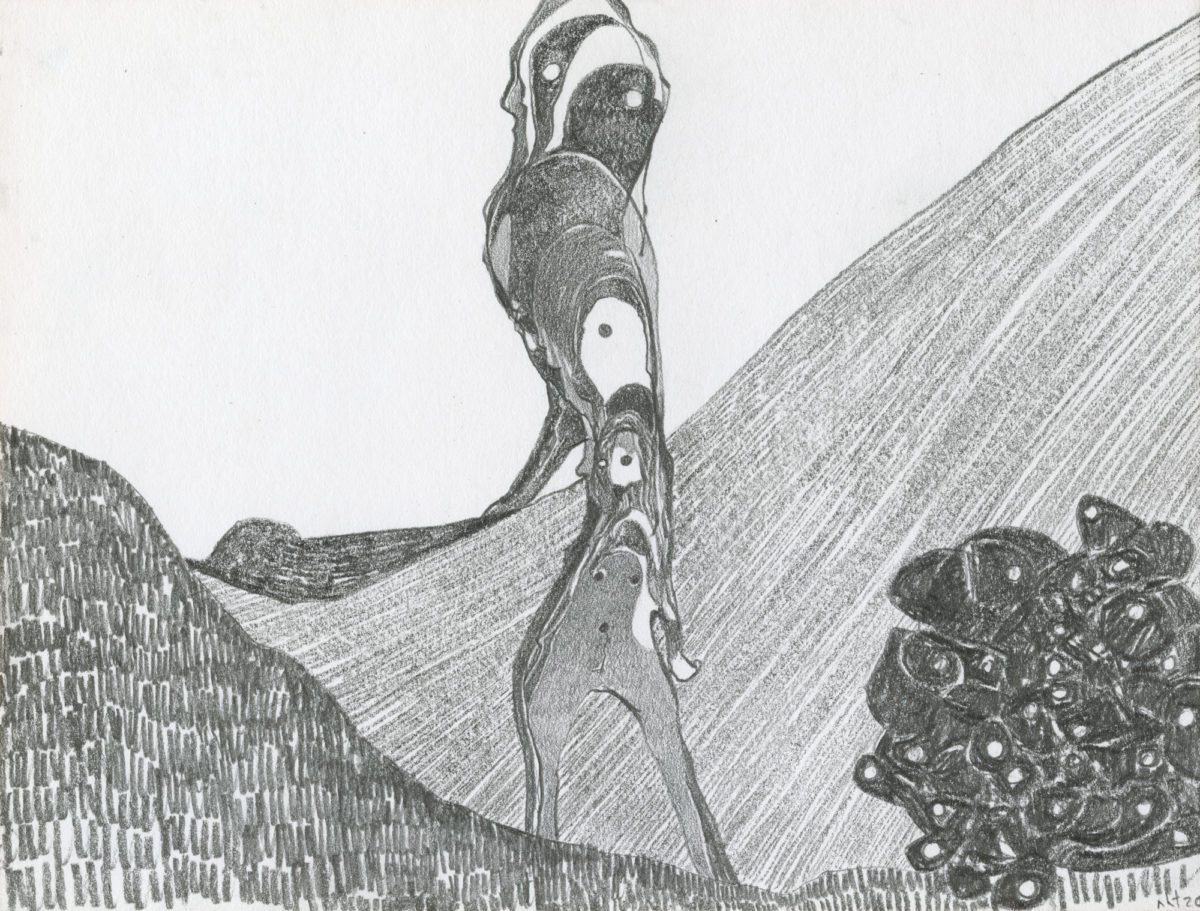

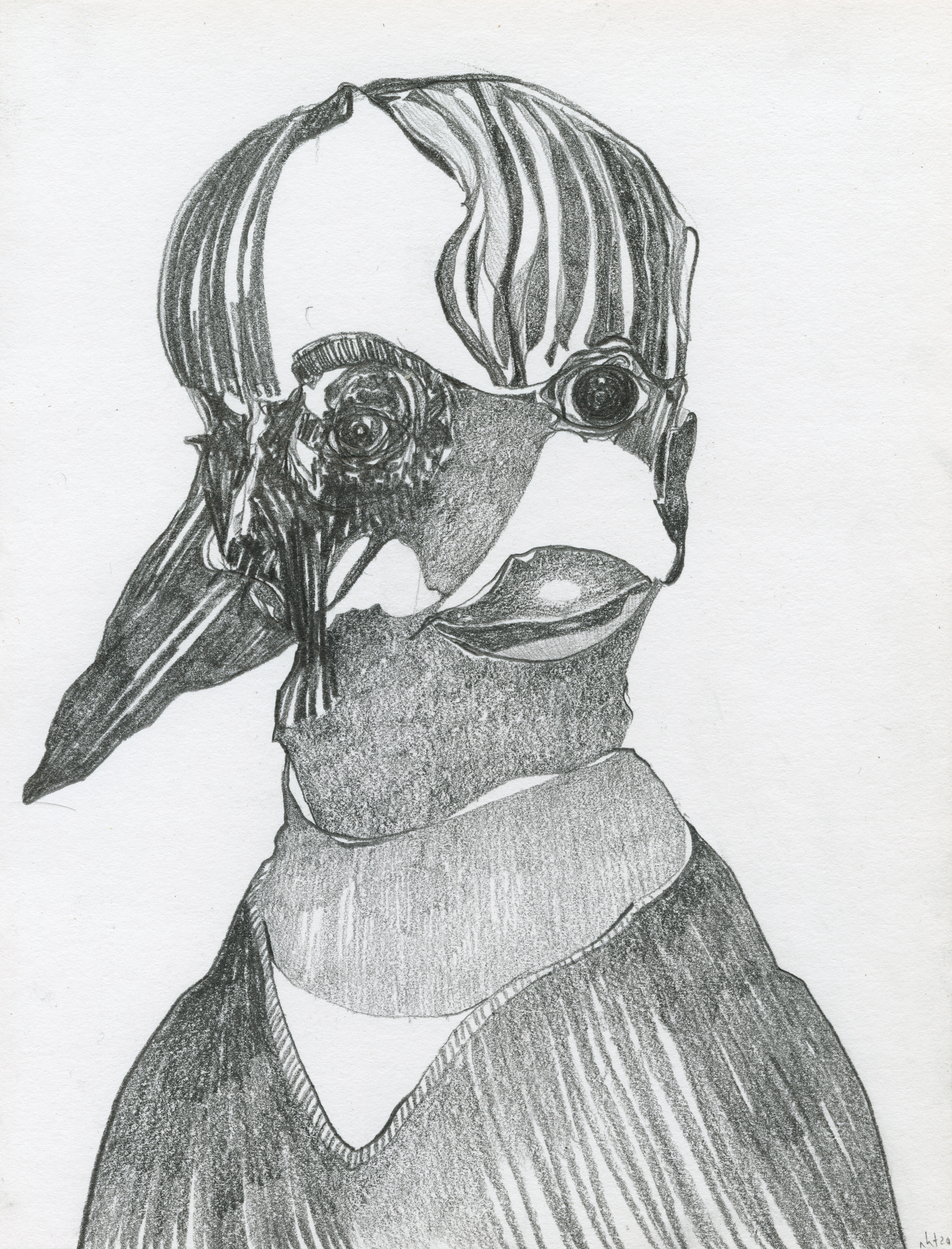

Nicola Tyson’s paintings and drawings are unsettling, amusing and decidedly mysterious. Exploring psychology, gut feelings and identity politics, the human and animal figures in her works often appear to be morphing from one thing into another, refusing to sit neatly in a single category, or reveal themselves as completely familiar to their viewer. A bird’s beak here and a large hoof there might hint at specific creatures, but this is as far as the British artist will go to offer clarity.

A selection of her pencil drawings are currently on view on Petzel gallery’s digital platform, including videos which show their creation. Unlike her paintings, the drawings are created instinctively, and often go in directions which surprise even her. They are open to interpretation, and therefore often reflect the psychology of her viewer. To someone who has been cooped up indoors for the best part of two months, I’d say this latest selection mirrors the unnerving uncertainty of our current moment. I caught up with the artist, speaking from her home just north of New York City.

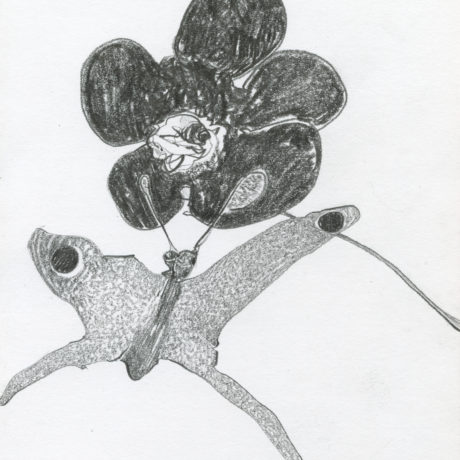

- Left: Upward Dog, 2020; Right: Totem, 2020

You have previously said that your works explore “psycho-figuration”. Do you express your own psychology in these pieces, or are you tapping into a more universal feeling?

It’s not a direct expression of my own psychology. When I stopped working so much with theory, I wanted to tap into something beyond language. Rather than being directly expressive, I use it as a source to make interesting forms. I’m too British, or skeptical, to be completely expressive! Humour is very important and I always try to use it temper any pretension that might come up. Humour delivers unfamiliar stuff in a friendly way, and it also goes past language, past that part of your brain to somewhere deeper. I don’t want to put that deep psychological stuff into words; I want to just drag it up, straight out, and make an image that creates some cognitive dissonance.

Is your process quite instinctive then?

My drawing is totally intuitive. When I start, I really don’t know what’s going to come up. It’s like putting a pencil on one part of your insides, and then just drawing it out, like a map, and not knowing what is going to unfurl in front of you. That is the excitement for me: not knowing where it is going. My painting is much more deliberate, because of the nature of it; it’s much slower.

“It took me a while to get to a point where I felt I had the creative authority to say I was an artist”

You started out photographing nightlife and subcultures in the seventies. Does this work feed into your artistic process now? Did it change the way you think about human subjects and bodily forms?

It took me a while to get to a point where I felt I had the creative authority to say I was an artist. I didn’t have that kind of upbringing, and I was encouraged to do something that would earn me a living. Instead of studying drawing I went to do graphic design. Back then, graphic design and art were two totally different worlds. I knocked around in the design world for a while and I was going clubbing. That’s when I took those early photos, and I don’t really see them as art, I see them as reportage. In that period, I felt like I was documenting other people’s creativity, until I got to a point where I could say: I don’t want this anymore, I want to be an artist.

I went back to art school to study painting, but the photography was all part of my exploration and finding my voice. The one thread I do see is that I was really good at catching moments, where everything seemed most alive. I was doing that in the paparazzi sort of stuff in the club, catching these moments that were very euphoric looking. And I still like that, to conjure up a presence and have it very alive, at its maximum moment.

You have explored identity politics and gender binaries a lot in your practice over the last few decades. The conversation has developed so much in recent years. How do you feel about this, and does it make you view any of your earlier work in a different light?

I mean, it’s changed even since I published Dead Letter Men in 2013, which I wrote all the letters for in 2011. It was quite a different world then. The subject is quite personal for me. When I was a child, I was a complete… I mean, tomboy isn’t the word, I really wanted to be a boy. I dressed as a boy, and I passed as a boy, and my mother let me get on with it. I always wonder what would have happened if that was today.

- Left: Blue Collar, 2019; Right: Self-Portrait: Then, 2019

It was a struggle through my teens to find what was comfortable for me on that spectrum—as we call it now, back then it didn’t really exist. Punk and all of the club scenes I was involved in in my teens were absolutely essential to help me get through that period. I wasn’t going to fit in in suburban London. Coming up through those London scenes were so important for my development as an artist and being comfortable in my own skin.

With the conversation now: it’s a conversation about fluidity yet people on both sides take such hardline positions. That’s the thing that gets me down. It should be about relaxing and not making more rules. It engenders a lot of antagonism. But obviously it’s not always easy, depending on what your situation is, and what your family life is. There is so much intense pressure on young people now from so many different angles, with social media and everything.

“I still like that, to conjure up a presence and have it very alive, at its maximum moment”

You have engaged heavily with feminist theory over the years as well. I grew up in the nineties and noughties, and I don’t think I even heard the word feminism at school. It feels like young women are growing up in a much more exploratory time now. How has it felt for you to see the latest resurgence?

It was such a big thing in the seventies and eighties when I was growing up, and everybody was talking about it. Then there was the backlash in the nineties and first decade of the 2000s. Nobody was talking about it, and it was very disturbing. There was the whole ladism thing going on. When I wrote the letters in 2011, it was partly out of an anger at that, because people had forgotten some stuff. It was really frightening how it all fell away and became really uncool. But it’s great how it’s come back again, and it’s come back in such a different way. The high theory moment of the eighties was quite daunting, you couldn’t understand half the stuff if you weren’t studying it at university because so much of it was deeply psychoanalytic. It’s funny seeing it come back so much more popular and user-friendly, which is good!