Who are the men that appear in your paintings, sculptures and drawings, and how much of a story do you develop around them in your mind?

The men are from magazines and sometimes photos on the internet. I don’t make stuff from life. I still have a lot of the magazines I bought growing up. Now I buy 10 Men, Arena Homme Plus, new titles like that, but don’t consciously use them. I think my idea of masculinity, alongside my imagination, must have formed in the dark, in the closet. If any story develops it’s a very short one. I’ve noticed that I don’t try to capture likeness but seem instead to aim at a new image that captures a version of masculinity. Sometimes I get it wrong, the real thing eludes me.

Could you describe your background and where you grew up? How much did art feature in your upbringing, and what led you to a career as an artist?

I grew up in South Shields at the mouth of the River Tyne. My school was heavy on sports but it had a really good art department as well. At home I was surrounded from an early age by cars and motorbikes. Both my brothers were constantly fixing and racing them. I really like the smell of garages and also to have tools and stuff like that around is very nice, very reassuring to me. At school we went on a trip to Paris to see the Musée d’Orsay and the Louvre, places like that. It had a big effect on me.

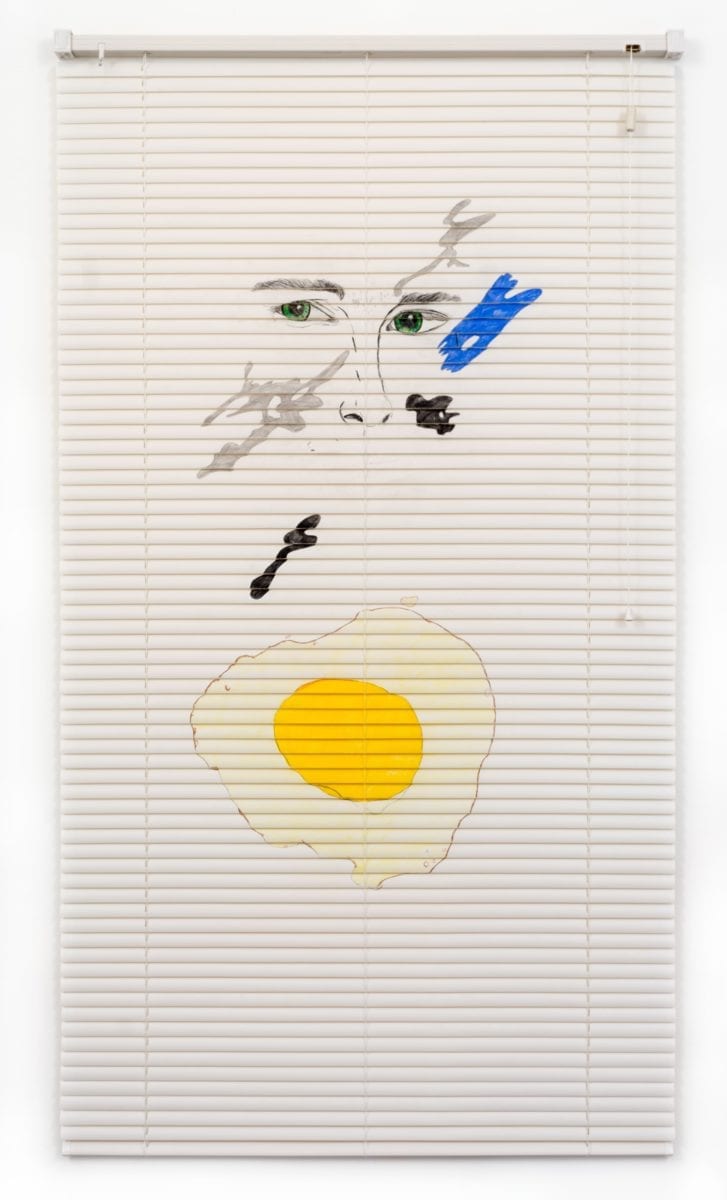

- Breakfast Choices, 2018

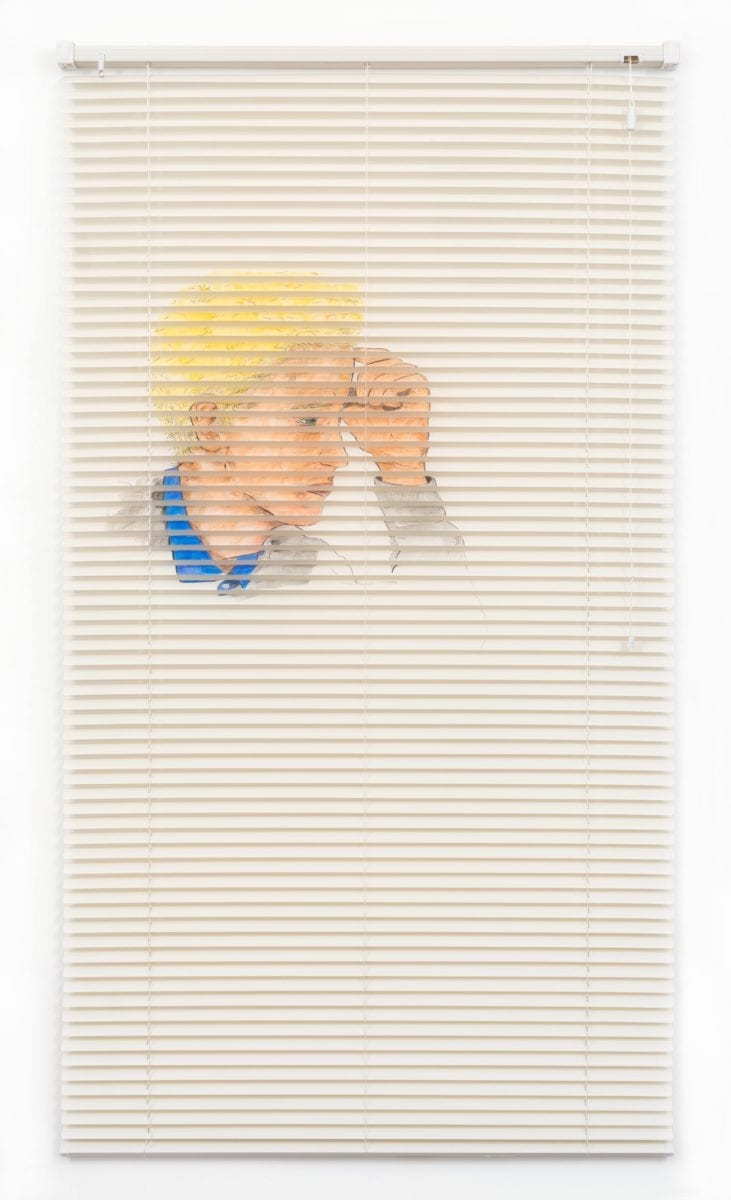

- Boy Thinking, 2018. Courtesy The Approach

“I think my idea of masculinity, alongside my imagination, must have formed in the dark, in the closet”

How important is queerness and sexuality in your work?

It’s a safe place to make work from, maybe a problematic one too. I’m privileged to have that to fall back on, but it can be too comfortable. In these times how different or more difficult would it be for me as an artist if I was a straight man making images of young women? Sometimes I wonder what I would do for inspiration if I hadn’t struggled for years to accept who I am and forged this way of making.

Recently, you have been painting and sketching on slatted window blinds. What have been the benefits and the challenges of working in this way?

The blinds are strange. I find it really difficult to draw on paper. For some reason the blinds, despite being physically awkward to draw on—they move around, they slip—really free me up. When I work I just don’t see them. It’s like they have a negative psychological presence that recedes and allows me license in whatever I draw on top.

You also work with groups of teenage boys. For their performances at your exhibitions, you ask them to hang out together, drink beer, eat chips, listen to music and generally behave as normal teenagers. What led you to develop this aspect of your practice, and what interests you about teenage boys specifically?

I was helping a friend, the artist Athena Papadopoulos, stage a performance at Tate Exchange with Yung Lean. A lot of his fans are kids with a very strong identity. I had my first solo show coming up, at Almanac in London, and asked one of them if he would like to be part of it. His friends were interested too and it grew from that. There was no plan. On the spur of the moment, I said I just wanted them to hang out at the show in some customized hoodies.

One of them helped in the studio for a few weeks to finish sculptures and paintings. We talked a lot—identity, sexuality, faith, music, teenage exploitation, art, philosophy, my intentions for the performance itself. Usual stuff. It helped me to get an idea of him and the others as individuals and not just extras. They bring a very interesting and active energy to an opening night. They aren’t world weary.

“The feel of things around me when I was growing up has filtered into what I do. I still make a lot of my work in my bedroom”

What are some of your memories of your own teenage years, and how have they influenced the work that you make today?

On Saturdays I used to go down town and buy music at Woolworths and stationery and magazines at WH Smith. When CDs came out I bought Whitney Houston and the Communards. The first band I saw live was the Pixies. I remember reading Less Than Zero and the Rules of Attraction by Bret Easton Ellis and Terry Brooks’s Shannara Trilogy. The feel of things around me when I was growing up has filtered into what I do. I still make a lot of my work in my bedroom. Drawing is best, it’s less messy.

You often embroider logos or other symbols onto clothing as part of your work. What interests you about the signals that we each project and align ourselves with (even unconsciously)?

Our dependence on them fascinates me. Even my attempt to subvert it buys into this power.

In a few words, what does masculinity mean to you?

Strong masculine energy. Shifting and mysterious. Embracing and resisting definition.