Our fascination with photographing the human form might come across as slightly egocentric. As a species, are we just a bit too self-obsessed? The answer, is probably yes. But as the works at Rotterdam’s Haute Photographie show, there’s more to photographic depictions of the human body than fashion shoots and selfies.

In the midst of the current climate emergency, it can be easy to forget that humans are just as much a part of the natural world as the icebergs melting at the Earth’s poles. Ernst Coppejans’s portraits from Bangladesh show people comfortable in nature, even waist-deep in river water. Similarly, the subject of Kevin Osepa’s portrait Blou Blous (2019), in his blue jeans and bright body paint, almost blends into his aquatic surroundings. The subjects are at home in the water, reminding us that at 60 per cent H2O ourselves, we’re all just human water balloons sloshing about the place.

“As a species, are we just a bit too self-obsessed?”

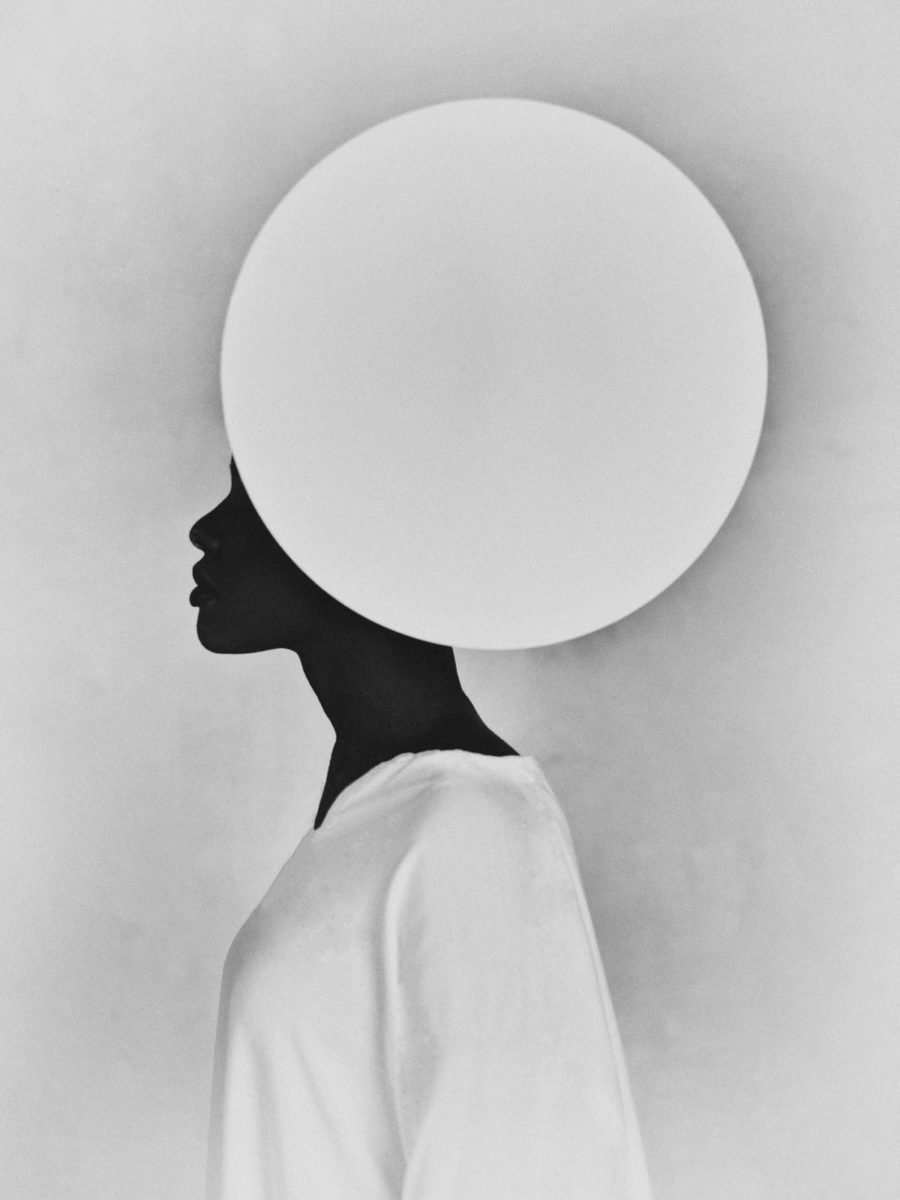

Kumi Oguro’s Island (2015) further displays the human fascination with water. In the photograph, the subject’s hair snakes out like tendrils of sand into the sea of the blue tabletop. “No man is an island,” said John Dunne, which is disappointing, because Oguro makes it look really soothing. There’s something tempting about the pose, about obscuring your face and hiding in the landscape. There’s a reason we think of nature as a mother, as it radiates calm and reassurance. Victoire Eouzan also finds a comparison between nature and a parent in her series, When the Mountain Took the Place of My Father (2019). She sees her photographs as portraits of the mountains, and through their personification she keeps the memory

of her late father alive.

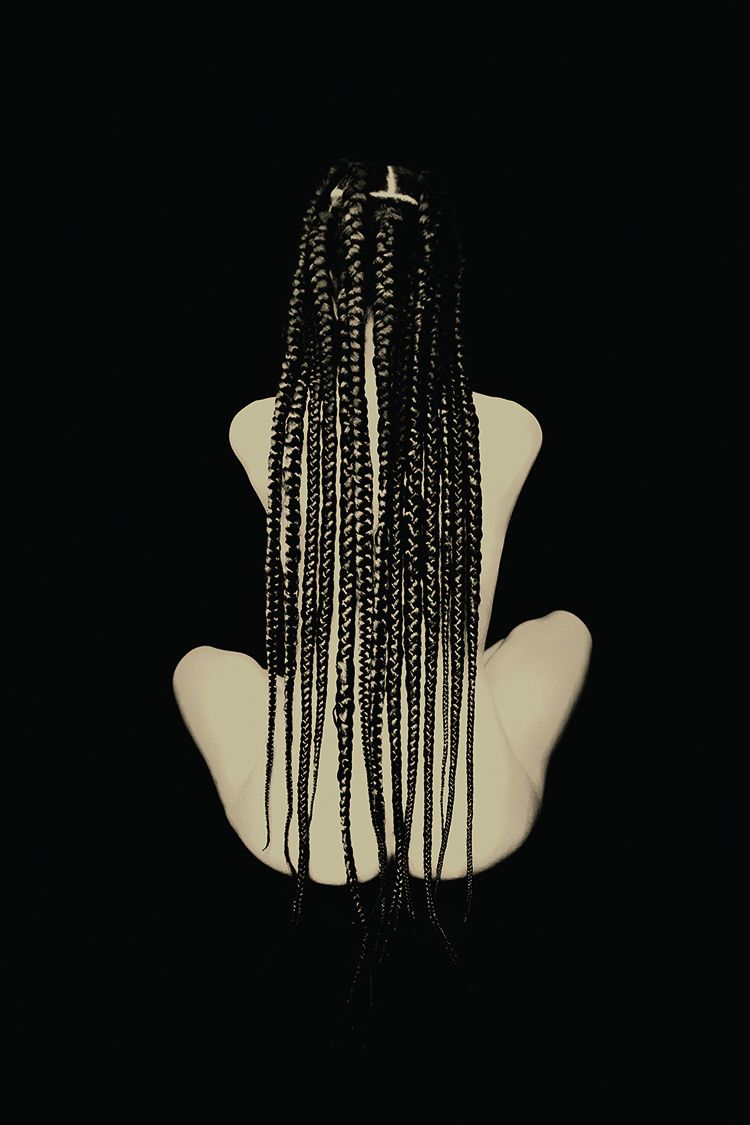

In Carla van de Puttelaar’s Untitled image from her Rembrandt series (2016), two women sit and lie atop a white tablecloth, in place of the usual apples

, grapes and dead pheasants of a baroque still life. The women avoid the gaze of the camera and lie expressionless, their humanity not emphasized. The women are objectified without being sexualized, the harmony of their lines and forms defined without being erotic.

“There’s a reason we think of nature as a mother, as it radiates calm and reassurance”

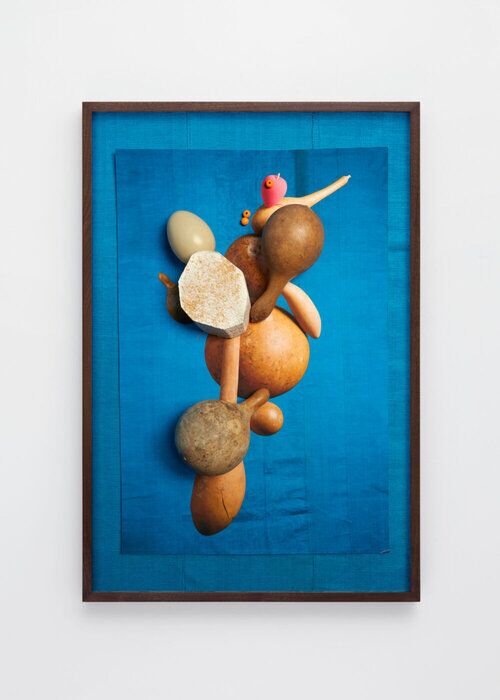

Lorenzo Vitturi’s pokes further at this line between human subject and natural object in his photograph, Yam, Calabashes, Aso-oke, Egg and Pink Sponge (2017). Despite featuring objects more traditionally considered congruous with a still life, his photograph somehow looks far more like a portrait than Van de Puttelaar’s.

In Roger Ballen’s Selma Blair and Sphinx (2005), the Hollywood actress and a cat look at the camera, with their bodies turned away, as though the photographer has surprised them with the flash. With her face mask, headband and stilettos sharp as cats’ claws, Blair seems almost more feline than the actual cat. As with much of the work on show at Haute Photographie, the photograph brings us to question the categories we take for granted, and to wonder where the line between the human and the animal lies in human nature.