Can you tell me a little about the idea of balance in your work?

The idea is that there is always a point of gravity, a centre within each one of us, which we try to maintain in everyday life, but the constraints, conventions and pressures of the world try to push us away from it. The struggle to uphold it is what I am contemplating in my exhibition; and not only that, but also whether there is balance in the world. There are so many imbalances that we need to address. I am inviting people to meditate on this.

Is it a meditative response that you would say you’re primarily aiming for in your viewers?

Yes but it is also more than that. In 2003 I started collecting authentic boats that were used to carry undocumented migrants from Turkey to the shores of the Greek islands and with them I made a series of public installations. I created them for the viewers to think about the issue of undocumented and forced migration but also to feel or imagine what this journey meant. My aim was for people to sense how it feels to be sitting in one of these vessels, making the jump between life and death.

In your work you often have the human body present, but with a work like Primal Boats, you’re talking about people who aren’t present at all. Is this a decision very early on in the making of a work, whether or not to include the body?

I see the boats themselves as human bodies; because of their shape, they are like shells. They represent not only the boats that I found, but also the people who travelled in them. The position of the boats facing down is like a position of death; it’s a compilation of sadness, despair and death and they were intentionally set up right next to the Brandenburg gate, which is triumphant, so as to underline the contrast.

Although Primal Boats was made in 2003 it is obviously a very current issue right now, the image of boats in particular. Do you think seeing these in an art context allows for a more emotional response than seeing images in the news every day.

I believe that if you’re inundated with so much information about this tragedy, it is very difficult to connect. It is much easier to be involved if someone tells you that a person you know is suffering, and then you jump in and help. But there are millions of people suffering now, so how can you approach it? You just ignore it, get on with your own life and hope for the best. I feel that art connects you with your neighbour, it brings you closer to the reality of life.

Thinking of balance, there seems to be a belief that the world is getting progressively worse. You’ve been making work with political influences for quite some time, do you believe this?

I’m afraid I do. It’s a pessimistic viewpoint and I’m not saying there is no light, but I feel that gradually we are moving into much more difficult times. I think that greed and egotistical behaviors have made things worse. At the beginning [of the refugee crisis], when we started having a few thousand people coming across, the human aspect to it was very present, but as we face this ‘tsunami’ of change it is evident that we ourselves are feeling threatened by it. But, as Westerners, we intervened in to those countries and we are partly responsible for this crisis. The solution is not to close the door and leave it all outside. We need to address all that we have caused there and think about what the world demands. I started collecting the boats in 2003 and now we are in 2016; it escalates from day to day. What is remarkable in the Greek islands is the people’s reaction to the tragedy. In this terrible economic crisis you see that people will find something to offer, and this is very moving. I feel this is very human.

Looking back to your early years as an artist, what was your medium? And have your interests stayed in the same area?

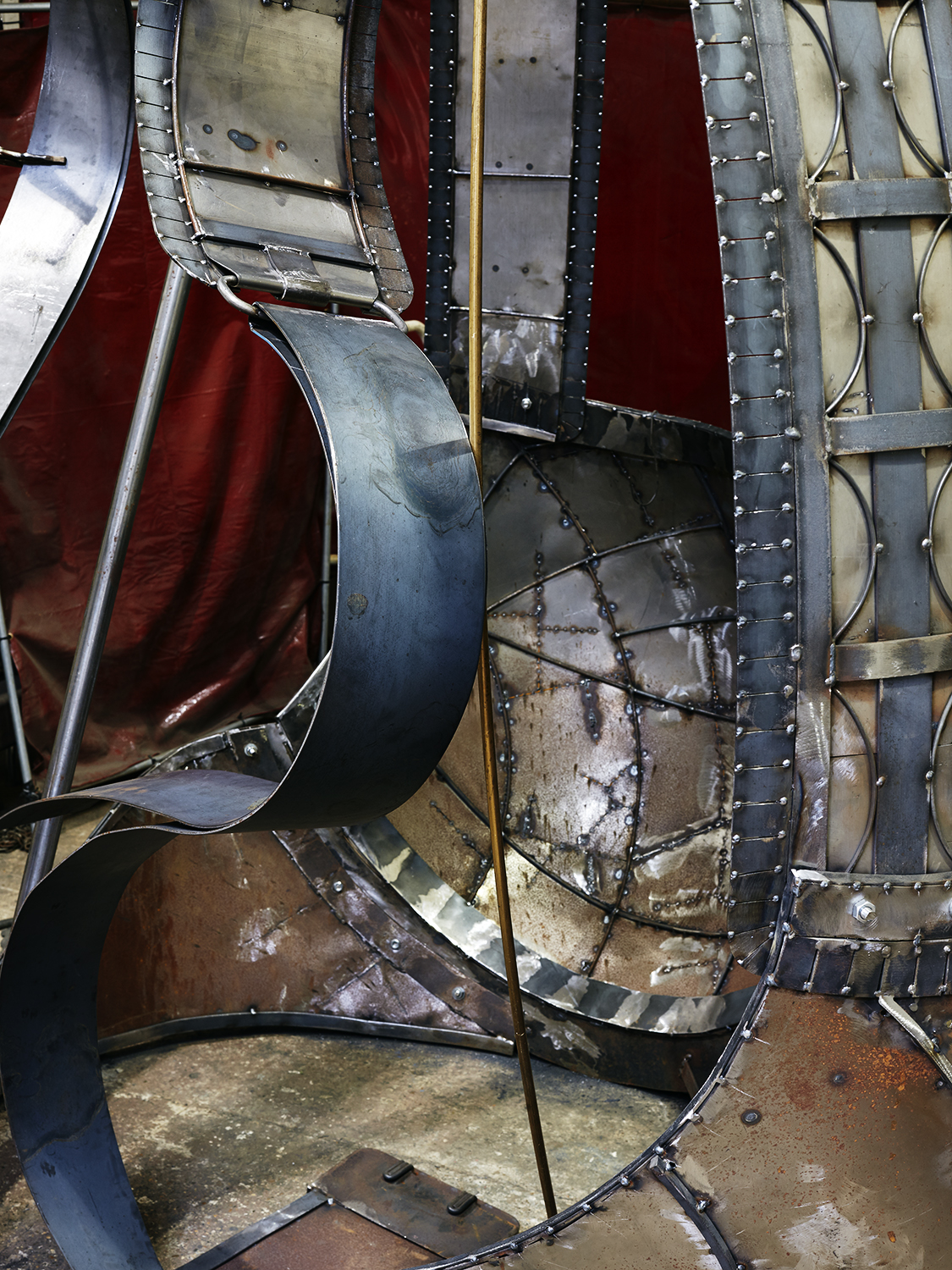

I started so long ago, but at first I was painting. When I started here in London, for a long time during my studies and my early years, I was trying—not consciously–to fit in with what was happening around me and to push myself in the same direction that my fellow students were going. In the end, I realized I wasn’t saying what I really wanted to express with my art. At some point about 20 years ago I started working on sculpture. I love colour, but I feel that the three dimensions represent me better and lately I’ve also moved to experimenting with video; what I do is create sculptures that are featured in the videos.

How closely do you work with the people who create some of the larger sculptures?

It depends on the work. For the resin and the fibreglass pieces I have expert technicians. When I do clay modelling, I do it by myself, or with the help of other people, if the piece is really huge. I get help according to each piece as it develops. A lot of the small sculptures that are shown at Gazelli Art House I made myself.

It’s enjoyable that even on a huge scale there is the handmade element to it. We’re used to seeing sculptures that are factory finished, there is something with your work that feels as though a hand has been involved.

Yes, the human touch. It is so comforting to have the fingertips of the artist on the work. It’s human.

Do you always feel best working to a large scale?

It is large, but not extremely large. When the work is really big I use objects that carry human beings—as with the boats from the Crossings installations. Inspired and influenced by my Greek roots, where philosophically the human is at the centre of everything, the human being is the measure. I started with the form of the human being and it remains involved in all my art even when it is not actually present.

Has the female figure been quite a prominent subject for you throughout?

I use the female figure often in my work, but I do not focus only on women’s issues; rather I address the human being. When I talk about peace and balance, this is a universal issue. But women have been suppressed and compromised, and the fight that they put on is a reaction to what they have faced and there is a balance to be achieved there. In 2013, I had an exhibition at the Istanbul Biennial that talked about the abuse that women and children face.

Do you feel that you consider the balance when you’re talking about something violent, in how violent the work itself is going to look?

When I’m doing the work I’m trying to present it as close as possible to the truth I want to express and the question of balance applies mainly to aesthetics.

There is an earthiness to some of the bodies—even the ones without heads—they feel as though there is a sense of womanliness to them that isn’t vulgar or demeaning.

Yes, in particular with my work Memory, the female body has a huge empty space inside that the viewer can see. This is what I consider the creative area of the woman, where she keeps all of her memory, the pain and the suffering. She has her legs amputated and open. I didn’t do this because I wanted to present something vulgar, but because I wanted to present a deeper reality of what is going on. Amputated, no head, no arms, no legs; seen as an object, and yet containing so much pain.

There is even a smoothness to the amputations. It’s not a graphic pain, there is a sense of dignity.

Yes, one of my primary concerns is the abuse of human dignity. These sculptures, a mix of female and animal form, aim to make a statement that although a person may have suffered violence and mistreatment, they still maintain their dignity.

‘Kalliopi Lemos: In Balance’ is showing at Gazelli Art House until 26 April. Photographs © Tim Smyth.