This year Mika Rottenberg nominates fellow New York-based artist Laleh Khorramian for the Vasseur BALTIC Artists’ Award. Khorramian’s presentation at the biennial exhibition marks a significant point of expansion in a practice guided by inner worlds and imagined histories.

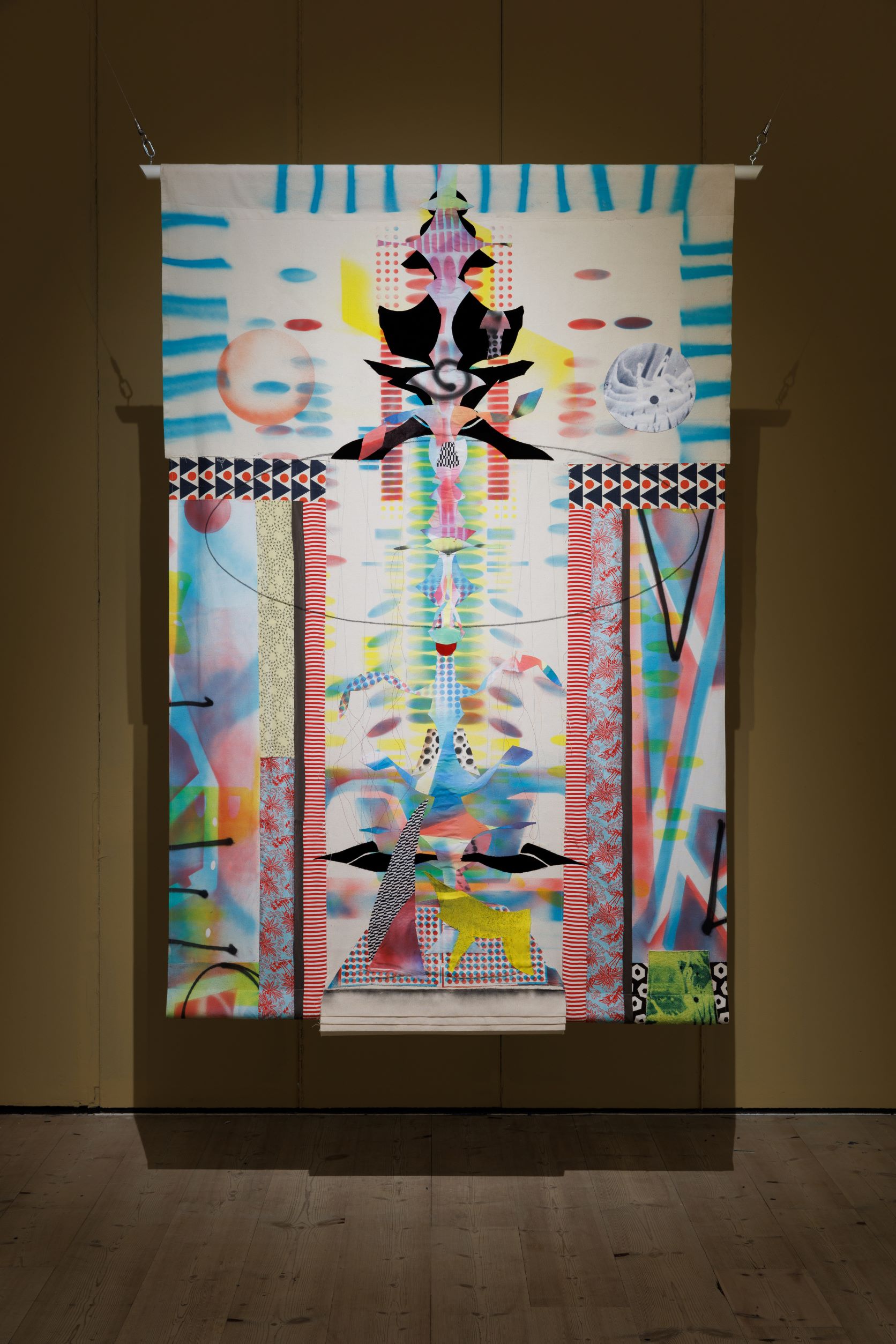

Across a series of banners, semi-human figures coalesce amid tangles of overlapping shapes and patterns, like the hidden contents of a magic eye puzzle. Sprawling lattices of stencil-work stretch over the surface of giant kimono, which divides the space like a stage curtain. Beyond, a gallery wall has been removed to reveal a ceiling-height window, overlaid with a vinyl mural: an enlarged section of monoprint which glows like an otherworldly forest.

Inflected with the artists’ characteristic registers of the surreal and the absurd, Rottenberg and Khorramian’s work visualises vast, overarching systems, from networks of labour and capitalist extraction to cosmological landscapes and sacred geometries.

In a conversation which orbits around process, production, and material, the long-time friends and former studio-mates discuss their distinct approaches to making work.

Mika Rottenberg: I remember you very clearly from the first day of school: you brought your dad, which was very cute. Sometimes you meet someone and you’re like, “I think my life is going to be entangled with this person,” but it takes a few years to grow.

Laleh Khorramian: It was after school, when we shared a studio for some years, that we really became more connected and witnessed each other’s work every day, which is such an intimate thing.

MR: It was the best studio ever! Especially when they opened a club next door. We became friends with the guy who ran it and lived in it. On weekdays, it was like our private club.

LK: It was this super run down, mouldy old brewery in Harlem. It wasn’t even supposed to be occupied.

MR: Then we both moved upstate at the same time and always kind of stayed nearby each other.

LK: Making work in the same space, I was always fascinated by your process, which is so different to mine. You were always very inspiring to me because of your focus and efficiency. A week before a show you were ready, you were done.

MR: We’re different like that. I’ve seen, with this show, how you really let things cook and simmer. You might disappear for two months and then come back with this amazing thing that seems like it’s been years in the making. When the time comes, you’re just like, razor sharp, and you make it happen like magic.

LK: The nature of our work is different I think because of our processes. You create these environments and machineries and see them through from beginning to end. I don’t necessarily know what I’m making: I produce drawings and paintings and they come together to show me the way, but I don’t start with an idea then follow it through. With your work, there’s still intuition and play, but also a good degree of organisation.

MR: I function in that way because I have to work to this point of execution, which is almost like a process removed from my conceiving of the work, whether that’s filming or fabrication. I work with actors and collaborators a lot. You have a much more hands-on studio practice, which means you can remain playful until the end because you can make changes at any point. Every time I come to your studio it’s a magical place.

“I produce drawings and paintings and they come together to show me the way, but I don’t start with an idea then follow it through”

LK: I’ve worked with other people when it comes to, say, mixing sound or making music, but collaboration hasn’t always been a relaxing thing for me. You have to know what you’re talking about, and I found this pressure to be so clear about everything that’s going on very stressful, perhaps because my work is so interior in a sense.

In my early twenties, I studied 16mm film. I dreamed of working with it in some way, but I was a painter: I didn’t know what that would look like if I didn’t want to direct people or explain my ideas to others. It was almost ten years later that I came to animation. I realised I could make a drawing do what I wanted it to do much more easily than I could explain that direction to somebody, especially if I was working with a surreal kind of imagery and movement.

MR: Animation allows for that combination of film and studio practice. Sometimes I think we should collaborate. It would be amazing to work on an animation together. As you know, I’m actually doing a big collaboration now with someone you introduced me to. We’re making a movie together, with you as part of wardrobe and textiles, so that’s a start.

It’s funny, when you said you were going to start making clothes, I didn’t really know what you were talking about. Then suddenly, you’re out with a whole line of amazing dresses and fabrics and prints. It’s a big part of the BALTIC show, and your process in general.

“Very hard to talk about in my work are things that are very interior or very cosmological, like past and future and what we’re all made up of as humans”

LK: I guess the clothes weren’t so much a new thing for me. It was never a secret, but maybe I dismissed it a little. Growing up, my aunt had a tailoring shop, and I spent every other day sitting in scraps of fabric, which must have sunk in, because I still do that. I learned to sew very young: it’s in my blood. I just didn’t take it seriously. I thought it was something I just did for myself.

MR: It’s often the things that feel natural and easy, the things we take for granted, which end up being central. There’s a lot of power in recognising what comes easiest to you and owning it, instead of dismissing it. There’s this conception that if it’s easy, it can’t be worthwhile. That you have to suffer to make great things. But you let textiles be a medium in itself and gave it the respect and space it deserved.

LK: For the BALTIC show I wanted to work really large. I like to work with things I find in my studio, so I started with large pieces of canvas that I used as drop cloths for other paintings. This is intentional: I’ll use multiple drop cloths and layers of canvas when I’m stencilling on silk or making a painting, creating an imprint or residue of the event. Then I’ll work with that imprint as a base from which to create another work. I really like that sort of consequence creating a starting point.

At the beginning of the pandemic, I was working with a small group of people to make and distribute masks to those in need. I think we made about 10,000. After like four or five months of making masks I honestly didn’t know how I was going to go back to making work. I thought, “I’m just going to make masks for the rest of my life: this is it!”

MR: They’re really beautiful. I still wear mine all the time.

LK: Eventually, I started making painted masks: I would paint these large pieces of cotton then fold them up and cut patterns out of them. I inadvertently realised that I had all these offcuts, like long, symmetrical, skeletal shapes. They became like the spines out of which grew the creatures or figurative forms you see in the show.

MR: I think you were just working with paper before in this way, right? But that’s not a material that lends itself so easily to being cut and stuck back together in lots of different configurations: it’s more fragile. But fabrics are just meant to be sewn together and layered and printed on as many times as possible. That shift from paper to fabric as a material is a very productive jump.

LK: I wanted to make big works but building giant canvases just wasn’t feasible during the pandemic. So, I thought, “Why not let the works be free, and let them move?”

“There’s a lot of power in recognising what comes easiest to you and owning it”

MR: That’s what’s great about them, they have this monumentality without being monumental. You can roll them, fold them in your suitcase, send them anywhere, you maybe just need to iron them afterwards. Reusing materials offers a lot of flexibility too. I keep all my sets and props intact in my studio, so ideally one day I won’t have to get anything new when I start a production

But with you, this sense of reusing things really informs the work: things look like they’ve had other lives. With the layering, especially in the works which are sort of portraits, it feels like you’re visualising how the soul is made out of all of these scraps and patches, like you’re trying to sew together memories and feelings and experiences into one coherent thing that constantly wants to fall apart.

“It’s often the things that feel natural and easy, the things we take for granted, which end up being central”

LK: I like that. I think that’s something that’s very hard to talk about in my work: things that are very interior or very cosmological, like past and future and what we’re all made up of as humans. I want to see it all at the same time.

MR: It’s a visual, sensual, material thing. In language, it sounds all over the place. Maybe poetry can do it. But in an image, it may be able to hold itself together. Just about.

Chloe Carroll is a curator, writer and researcher based in London

The Vasseur BALTIC Artists’ Award 2022 is at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art until 2 October

Vasseur BALTIC Artists’ Award 2022

Read Hito Steyerl in conversation with nominee Fernando García-Dory

READ NOW