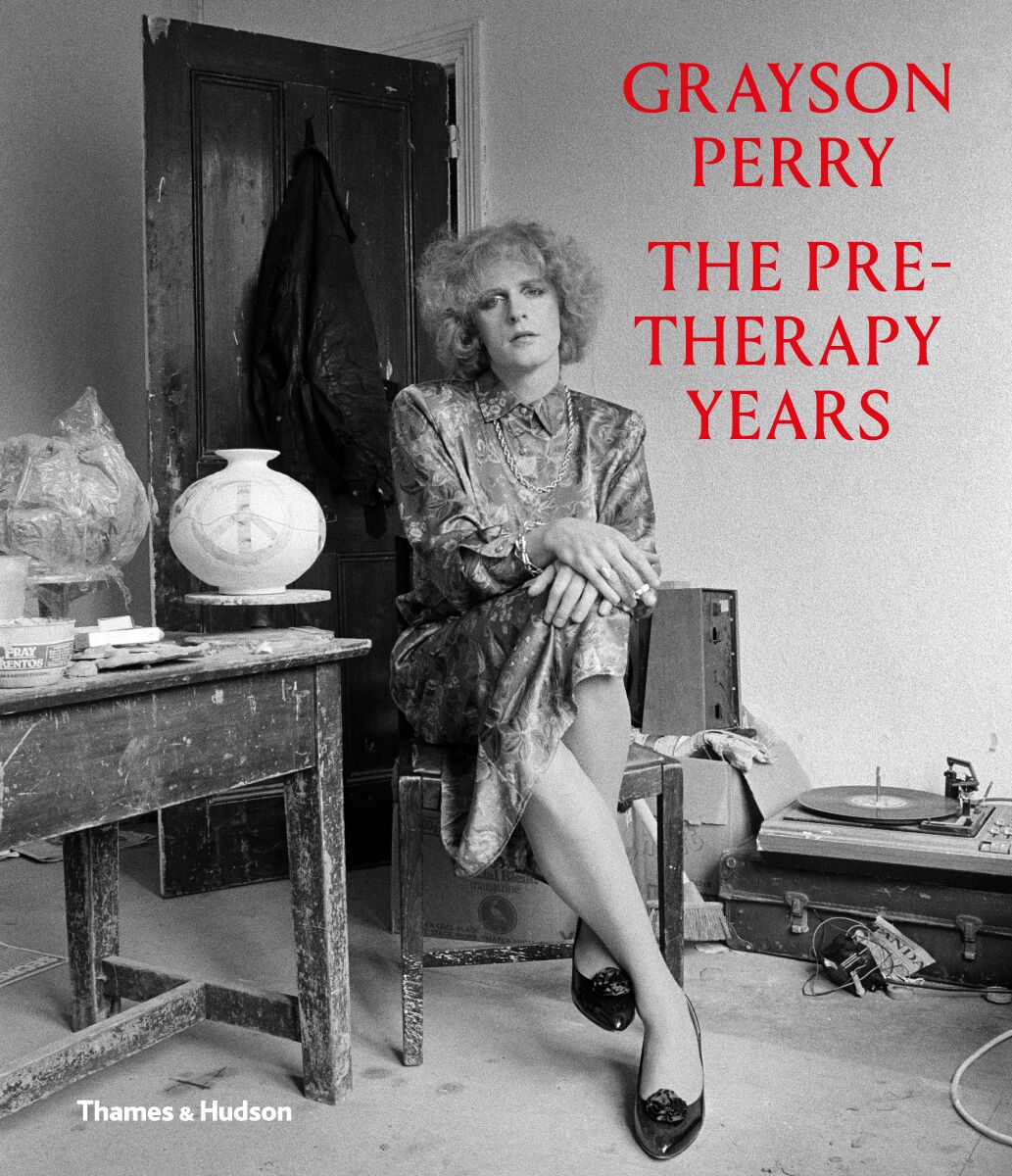

The world has come to know Grayson Perry (b. 1960) as a benevolent public influencer, his edge unthreateningly sheathed. When he isn’t coiling and firing his pots he is curating sell-out RA summer exhibitions or making TV shows about class and inclusivity in the arts. There are genitals and references to sadomasochistic kitsch on his pots, but these are things with which we have come to be fully comfortable. For just as long as we have been adapting to Perry’s personal symbology, we’ve also known his transvestite persona Claire: a fairy godmother dressed like a little girl. But long before Perry won the Turner Prize in 2003, and Claire occupied her fully-realized position of youthful innocence, the Essex artist and his alter ego had to do a lot of soul searching—as a new book Grayson Perry, The Pre-Therapy Years attests.

Part monograph about his early practice, part annotated catalogue to an exhibition of works made between 1982 and 1994 (currently on show at the Holburne Museum in Bath), the book intersperses essays by Andrew Wilson and Catrin Jones about Perry’s early work with the artist’s own commentary on glossily reproduced plates, urns, vases and other sculptures. The “pre-therapy” part of this refers to a line Perry has drawn in his development. In 1998 he started seeing a psychotherapist. Before that, he tended to work through his emotional baggage via his ceramics. You can tell. Judging by the looks of things—the hellhounds, fascist symbolism and misogynistic devil women depicted on the early pots analysed in this book—there were a lot of demons to exorcize.

- Untitled, Date Unknown

- Cocktail Party, 1989

For a quick precis of the material that formed him, much discussed in Perry’s own books, he was domestically abused by his milkman stepfather, with whom his mother had an affair before Perry’s father left. From the age of thirteen he dressed in his sister’s clothes, and was later thrown out of his father’s house when a diary describing his cross-dressing was discovered.

“In 1998 he started seeing a psychotherapist. Before that, he tended to work through his emotional baggage via his ceramics. You can tell”

In an essay from 1988, Perry described making an ashtray at school—now known as Yellow Ashtray (1968)—when he was eight or nine. This coincided with wearing a tight protective smock that made him “very excited”; or, in a separate remembrance: “[it] turned me on…I was being dressed like a small child, it felt very humiliating”. In this memory, gestures still evident in his current work—the transgressive, the manual, the domestic, the childlike, the sexual—seem to already be working together, and are neatly bound in his earliest experiences of both ceramics and the outward blurring of gender norms. These gestures can be observed, absolutely concentrated, in work he produced during the eighties and early nineties in London after graduating from Portsmouth Polytechnic; works many of which the artist himself hadn’t seen for decades, having sold them for £50 at early shows or left them unclaimed in the chaos afterwards.

Aggressive sexuality, bordering on misogyny, characterizes works like 1987s Cunt Power amphora. A woman opens her legs to reveal a wolf’s head in Beneath Every Stone is Life (1988). Perry incorporated the visual lexicon of fascism, Masonic insignia and Tarot iconography in many of these early works. Looking back at a 1985 plate called, with youthful nihilistic flatulence, The Terrible Unnatural Forms Is Immature Nature, Perry cannot remember why a corrupted pastoral scene of his native Essex features the Reichsadler—the Nazi imperial eagle herald holding a swastika in its talons: “To tell you the truth, I am mystified as to what I meant by the text and how it relates to the Nazi insignia,” he writes under a reproduction. “Perhaps it was a dark premonition of Brexit!”

A highlight of the work and of Perry’s commentary is 1984s Saint Diana (Let Them Eat Shit): a coronation throne with a clay poo standing in for a historical artefact. “The original in Westminster Abbey was made in 1300 to house the sacred Stone of Scone,” Perry tells us. “My miniature throne come commode houses a sacred turd. Perhaps inspired by Piero Manzoni’s Artist’s Shit (1961), I had tried to encase one of my own faeces in a block of resin, which ended in a smelly mess, so I made a fake one out of ceramic.” The possibly intentional, possibly developmental shoddiness of the decoration adds a convincing aura of worn or defaced medieval craftsmanship. Excellent work.

If anything, this book is most valuable for revealing to us what we already know. From the very start of our relationship with Perry in the mainstream, he was controversial and homely at the same time. On the one hand his ceramics were about sex and had genitalia all over them; he had a non-normative gender identity; and for the art world, he was working in ceramics. (Despite what the Bauhaus did 100 years ago to narrow the gap between fine art and the applied arts, and regardless of the variety of materials used for conceptual work in the nineties—beds, sharks—pottery was still set apart as a maker’s craft rather than an intellectual’s art.) Perry’s anxiety about where he stood regarding his medium was there all along. In 1987, an ironic eighteenth-century-looking text on the glazed ceramic Sales Pitch implores the potential buyer: “With your help I can take pottery into the arena of comment and ideas, dare I say it, fine art.”

But on the other side of this, the balance of all the above controversial aspects made him uniquely attractive to a wider public. The sexual content of his subjects was often bawdy with a tinge of caricature in the Beryl Cook sense: it tapped into humour as old as the British Isles. Britain, too, was culturally aware of drag and cross-dressing in a way that was entirely conventional and unthreatening to the normative status quo. Dame Edna Everage and Lily Savage were prime-time figures, softly matriarchal and pre-watershed acerbic respectively. Elsewhere drag queens were the licensed fools of provincial clubs: different to the norm and, because of this, permitted to shine a light on the norm.

“From the very start of our relationship with Perry as a public, he was controversial and homely at the same time”

Claire was far removed from these figures but the superficial association was, if anything, a way in for the public. As for the work, not being seen within haute-art territory made Perry’s medium perhaps more accessible again. His was more readily understandable and comforting as visual stimulus. He made pots! He made vases! “We all grow with the friendship of pots in our homes,” Perry has said. “A pot has no pretensions of becoming a great public work, we know where we stand with a plate or a vase.”

Perry was aware of this from as soon as he started taking pottery evening classes near his Camden squat in 1983. There he felt secret pleasure in adorning his fledgling attempts with cocks and swastikas in a room full of respectable middle-aged women. Perry counted on ceramics to always sugar the pill of message or obscenity: “I was an angry young man and I liked that, no matter how offensive the images I used, the fact they were on pots somehow neutered my provocations.” This wasn’t fully the case at the time. Other members of the class tried to get Perry kicked out. But later, when the stakes were higher, Perry knew he could rely on the humble “in” of his craft to act as an almost bland vessel for his ideas. With Grayson Perry, The Pre-Therapy Years, we can see throatier, raucous work that has none of the blandness or benignity of what we have come to know as Perry’s works, or his “brand”. Even if it could use some.