“Feminists are kindred spirits,” says Yinka Shonibare. He is on a stage at Christie’s auction house in London, in conversation with the director of 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, Touria El Glaoui. It is the start of Frieze 2018, and at the fair attempts are being made to address the gender gap—or, at least, the attempt itself is being made visible. Shonibare is wearing his usual outfit: a jacket in a muted colour, dark trousers and fresh-looking trainers. He speaks purposefully. Later, I sit next to the artist at a small dinner organized by South Africa’s Goodman Gallery, which represents him. I give him an impromptu grilling about what he has said about feminists, as we pick at plates of pasta and greens in the semi-lit restaurant.

“Groups that haven’t been historically treated well felt, especially in the eighties and nineties, a sense of unity,” he explains. “I do not feel I have a lot in common with the white males who have dominated the art world historically. Barbara Kruger, Rosemarie Trockel, Nancy Spero, Cindy Sherman, Judy Chicago—those were the people who I was really looking at when I was starting out. I had more sympathy with their work.”

A few days later, as if to confirm this, I meet Shonibare again by chance. He is looking at works by Nancy Spero in the Social Work section of Frieze. One of the works, made in 1979, reads: “Certainly Childbirth Is Our Mortality / We Who Are Women / For It Is Our Battle.” As women, we are used to being thought of as “other”, is this what connects Shonibare to feminists? “Absolutely,” he asserts. “To engage with fury, to be politicized… I have realized there is a correlation between the post-colonial and feminism.”

“I do not feel I have a lot in common with the white males who have dominated the art world historically”

At school in Nigeria, Shonibare always enjoyed art, and attended workshops at the National Museum in Lagos. But it was a trip to Italy with his parents, aged fourteen, that made him think he could make it his profession. “I had made a painting of the Colosseum, and then my uncle bought that painting from me. I decided I wanted to go to art school after that! I came to Wimbledon College of Arts to do a foundation degree.” It was while he was at Wimbledon that Shonibare fell ill. He was eighteen. “I got a virus in my spine that left me paralysed. I couldn’t go back to art school for about three years after that, and I went to Byam Shaw School of Art [since absorbed by Central St Martins] and then to Goldsmiths.”

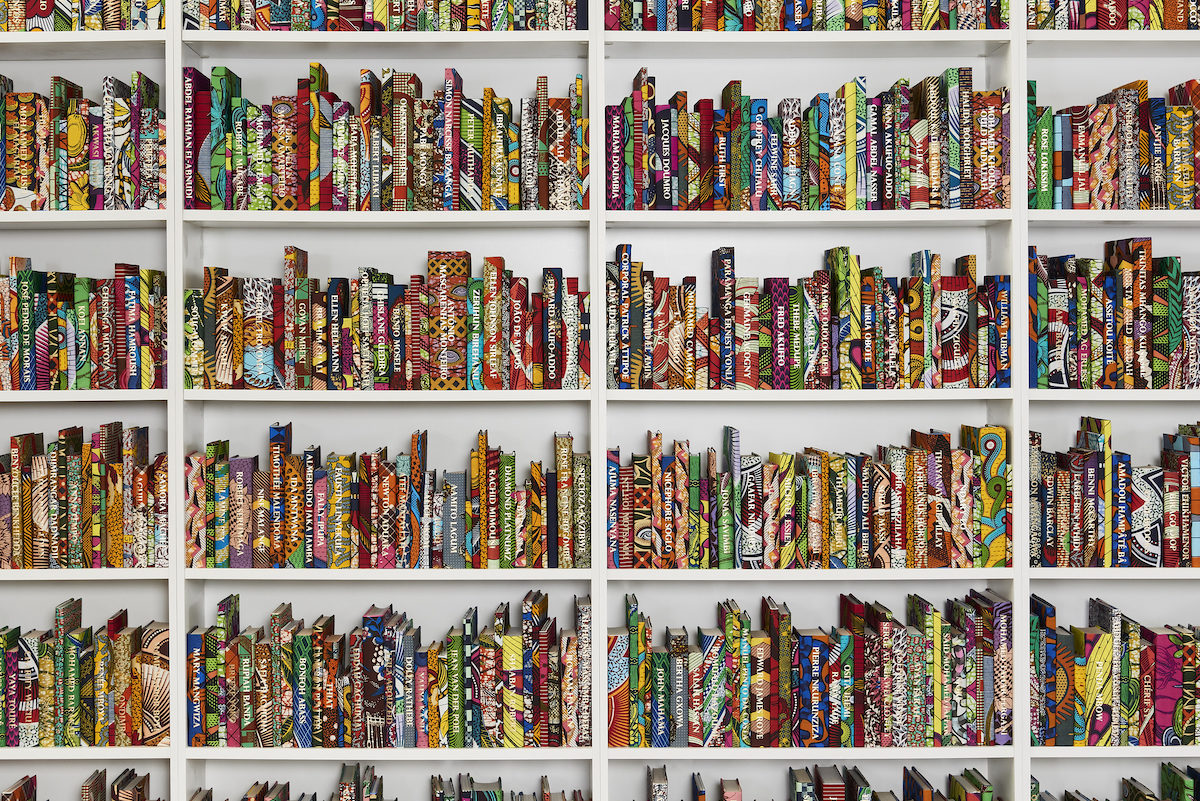

- African Library, 2018. Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery

Shonibare emerged in the 1990s as part of the YBA generation. He—like Emin and Hirst, who were at Goldsmiths at the same time—was “discovered” by Saatchi, at an ad hoc exhibition he’d put up in Chelsea. His current dealer of twenty-two years, Stephen Friedman, also picked Shonibare up from that show. The artist has been curating throughout his career, as an experiment at first, but then at more prestigious institutes including the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, Cooper Hewitt in New York, the Royal Academy in London and, most recently, the Arts Council England, where he also worked as a buyer for the collection.

For my generation, Shonibare is perhaps best known for his curatorial work and his public art, such as his replica of the HMS Victory in a bottle in Trafalgar Square in 2010 (the first time the Fourth Plinth had commissioned a black artist), or his billowing, fibreglass Wind Sculpture in 2013, which appeared in Yorkshire Sculpture Park and Central Park. In the last ten years he has also been very involved with the running of Guest Projects, a space for hosting experimental exhibitions and residencies at his studio on Broadway Market, and home to the popular Artist Dining Room, with suppers themed around an artist (all the proceeds are put back into the running of the space). Shonibare sees all these strands as connected and part of his practice: using his name to promote emerging artists, meeting people from all walks of life—these are the things, he explains, that he finds most valuable about his practice.

When I next speak to Shonibare it is a few hours before he flies out to Lagos to attend Art X

, the first fair in West Africa for contemporary art, set up by Tokini Peterside in 2016. It’s the first time Shonibare has participated in the fair programme, in the city he grew up in. He will soon be spending more time there, as he is in the process of setting up a space similar to Guest Projects, where he will run residencies for international artists and curators. “I think Nigeria is ready for this kind of thing. There are more spaces opening in Lagos, and more artists are finding buyers for their work—collectors are growing in number. It just seems to be the right time.” Building begins this year, and it should open to the public in 2020. “I think people are excited about the idea and seem desperate to have that kind of platform where they can exchange ideas. People going out there will be able to learn a lot from Nigeria, and vice versa,” he adds.

“I wanted to have my own freedom, freedom from the constraints of those gendered roles. I didn’t want to conform”

For decades now, Nigeria has been democratic and open to the world, but it is still, as Shonibare explains, “a very patriarchal society. It is traditional in many ways, and roles within that society are very gendered. In choosing to be an artist, I was already rebelling against that role, which my parents were not particularly pleased with. There was a possibility I would not be able to take on the role of the head of the family, as the breadwinner, to fulfil those roles expected of me. But I wanted to have my own freedom, freedom from the constraints of those gendered roles. I didn’t want to conform. And with the #MeToo movement I feel there has been a seismic disruption in power relations. I think unfortunately we’re seeing a very nasty backlash against that. Men being disgruntled that their toys have been taken away from them.”

When Shonibare has spoken about his own work in the past, he has often spoken of his interest in power: who has it, and why, who can take it away, who is allowed to deconstruct it. This is enriched by his perspective: as a black man, descended from Yoruba aristocracy who were once involved in the slave trade in Nigeria; as a disabled person; as a person with dual heritage; as an artist who has continually refused to conform with the established way of doing things, but who also accepted an MBE (in 2004, the same year he was nominated for the Turner Prize).

“I just don’t want to do stuff that society says I should be doing. I don’t think that makes me any less male, I just prefer to make up my own mind about what I want to do.” At dinner he tells me he wanted to be able to be weak, to be vulnerable—something that society doesn’t permit men. “It’s a false expectation. I don’t want to be superman, I can’t be—it’s too much responsibility. I’d rather not have that responsibility. I’d rather be human, just to be myself. If I feel pain, I want to be able to go through that. I don’t want to put up and shut up.”

“There are very macho creative people,” he adds. “But you find that, more often than not, creative people generally avoid being put in a box.” Shonibare does not, for example, like football. The Victorian Philanthropist’s Parlour is an installation he made in 1997, a glorious reproduction of an elegant Victorian-era living room but with the wall and furnishings covered in the printed Dutch wax cotton material Shonibare is best known for—that textile embedded with sociopolitics that has passed back and forth between West Africa and Brixton, Holland and Indonesia. His textile is printed with a motif of black football players, bought by European clubs. As Shonibare suggests, it’s part of an insidious form of colonialism that contributes to white wealth.

Shonibare has rebelled against traditional ideas about gender for decades. The materials and mediums he uses share an affinity with the radical feminists of the 1970s, re-appropriating “feminine” crafts and textiles. Sometimes he deals with gender directly: in the film, Un Ballo in Maschera—inspired by the assassination of the King Gustav III of Sweden, and the Iraq War—he prises physical power from men by changing the gender of the protagonists. Then there’s Big Boy, the gender ambivalent sculpture he made in 2004 that interrogates the depiction of gender and power in a formal way through shape and scale.

Gender reveals itself as a construct on his faceless figures, nothing more than a costume, as in the more recent sculptures, such as Clementia and Post-Colonial Globe Man, exhibited at Ruins Decorated in the autumn of 2018 at Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg. These new, “mongrelized” power figures interpret history; hybrid totems for a post-colonial world. “I’ve had people describing my work as exploring ‘meta-modernism’, alternating between opposites, and I think that’s what I do,” Shonibare tells me. I think of the work he did with the Royal Opera House, Odile and Odette, in which two ballerinas, one white, one black, appear to mirror each other. Shonibare describes it as a “very political piece, but the politics of it are incorporated into the movement”.

“If I feel pain, I want to be able to go through that. I don’t want to put up and shut up”

As #MeToo has proven, the structures that make us believe in those opposites, that establish the idea of binaries in order to keep the status quo, are often invisible; difficult to tackle and address. Can the visual arts help? “My activism, if you like, has always been within art practice,” Shonibare says. “That being said, I also consider myself an artist, in that I do have some kind of affinity with form, and I think even if a work is really political, it is important for me to still continue to engage the audience, formally as well as cerebrally.”

I ask if the biggest problem for all of us “others” is capitalism, after all, and isn’t he complicit, by being part of the market? He smiles wryly, with a mischievous flash in his eyes. “You can’t beat the whole system, you can’t destroy it—you have to be able to play the game,” he responds. “I’m very suspicious of ideologies. As we know historically, ideologies have not ended well, so I try to avoid those.” The work he seems most proud of is the exhibition he recently curated at Stephen Friedman, Talisman in the Age of Difference. “Particularly now, in the context of the rise of the far right in the US and Europe, the show seemed to happen at the right time, highlighting the work of artists from Africa and the African Diaspora across the globe. To give visibility to that work, particularly the emerging artists.”

Shonibare’s work, whether it is curating or creating, isn’t about wresting power from one to another. Power, after all, is ultimately a construct of the patriarchy. He does not want to be powerful. To live as a harmonious community, we have to do away with the notion of power completely.

This article originally featured in issue 38

BUY ISSUE 38