Why are H&M shoppers, who might never have been to a heavy metal gig, interested in buying T-shirts emblazoned with images of Black Sabbath? And what draws heavy metal bands towards the iconography of Catholicism and art history? British artist Tom Cardwell explores the tangled web of influence and borrowing that surrounds the thunderous music genre. During his recent Elephant Lab residency, he created a mix of canvas paintings and mixed-media works resembling banners and garments, unpicking—and in some cases further complicating—the subtle layers at play in the visual culture and fashion garments of heavy metal.

What have you been working on over the last month, and how has it developed from your original proposal?

It is broadly what I proposed I would do, which was to experiment with florescent paints. I started off making loads of samples with spray acrylic; I was playing around with paint to see what it does and trying different consistencies: watered down or layered. Then I started cutting the samples up and made this piece [shown above] first. The idea is that it could be worn; I might take it off the wall and drape it on something. I like that in-between suggestion, where it could be a painting or a garment.

I then moved onto a series of works which are made from sewing bits of the samples together, and I also added some screenprints that I made beforehand, and painted onto the works as well. I wanted those to be the same size as the canvases made for the second series, which are like trompe l’oeil paintings that replicate the first series.

How important is it for you to show the two series of works together? Do you eventually want the canvases to stand on their own?

If someone wanted to show them separately, I wouldn’t mind, but ideally they would be shown together. For some artists who work like this, the original is very much a model for the painting. But I feel like these could all be paintings in their own right.

What do you feel you get in the replicating the mixed-media works onto the canvases?

These are an attempt to bring together two ways of working that I’ve been doing almost in parallel. I’ve been working on the canvas paintings that are quite detailed for a long time—I used to make detailed paintings of things I didn’t have, so objects from museums and things—and then I first made banners more than ten years ago, but I didn’t quite know what to do with them. Over the years I’ve come back to them again and again, and it’s a counterpoint to how I typically work with canvas, which is very fastidious and slow.

More recently, I felt like I wanted them to come together. I was making paintings of clothing, and I thought this was the next stage, to take some of those textile constructions and include them in the work.

“The idea is that this work could be worn; I might take it off the wall and drape it on something. I like that in-between suggestion”

It feels like there is some humour about the nature of painting in showing those two ways of working together: you go through a laborious process to reproduce an item that you have already made very quickly.

It’s definitely a conceit, I suppose, and it’s kind of a ridiculous thing to do. In a way, any painting now is a ridiculous thing, because if you want to make an image quickly you can take a photo or use some graphic software that’s very quick. So for anyone who’s painting, and especially if you’re doing representational painting, there’s an element of slowness. I’ve always wanted to make things that take time to do. I don’t feel fully comfortable if it’s too quick. But there is something about the labour of making something detailed that I’ve always found very satisfying.

I reference old paintings directly in some of these works, but that is through photographs which are screenprinted—so it involves two quick processes, and it’s like a sampling. It is an attempt to bring together that idea of painting history—whatever that means—with something more contemporary.

What is it about religious and art historical imagery that you think appeals to the metal mindset?

I think metal culture has always drawn a lot from the past, even going back to early Black Sabbath or bands in the seventies when metal was forming. Bands like Led Zeppelin were really interested in folklore and spiritualism. There is a strand of metal that came out of folk music, which has always been about the past and trying to evoke something ancient.

Also, lyrically, bands have been interested in very spiritual stuff. A lot of that is contextualized through a Judeo-Christian set of images, symbols and stories, often focusing more on the dark forces. It’s the same as horror movies, they tend to use that imagery as a starting point, and most of that comes from religious texts or myths.

At the moment, there are Scandinavian strands of metal that are interested in Pagan mythology, and they use a lot of naturalistic landscape painting from the past as a way of evoking that spirit of nature. A lot of those paintings are very epic, and metal deals with very epic themes. Things like John Martin’s judgement paintings appeal. There is a commonality.

“There is a strand of metal that came out of folk music, which has always been about the past and trying to evoke something ancient”

There is a real sincerity in paintings by artists like John Martin, whereas a lot of contemporary art aims for irony. Do you think the way metal uses this imagery is ironic, or is there a sincerity in that genre that aligns well?

I think generally it is sincere. There is not much irony in metal, which isn’t to say that people in that scene don’t get irony—they definitely do, they have a sense of humour—but the rhetoric of metal is less ironic than other areas of culture. The way imagery is used is definitely much more straight up, and bands want it to be taken at face value. There are exceptions with people like the Darkness; they’re not a metal band but they have sent up metal. And within metal there are genres, like Pirate Metal, which are very tongue in cheek. But there is generally a lot of earnest appeal in it, even if there is a recognition that it is theatrical. Iron Maiden are very aware of the theatre of what they’re doing, but it’s quite subtle and there is a pretence that this is earnest.

Are you mostly interested in working with garments and notions of fashion in a wearable sense, or are you also interested in the recent revival and reworking of textiles in the art world?

The motivation in this body of work is around the appropriation of metal style by fashion. I am interested, for example, in Vetements doing a collection around black metal clothing and skinhead stuff. And then brands like Supreme have done collaborations with Black Sabbath and Slayer; I’m interested in how that changes what the original thing is. In a way, those things aren’t about metal, they are about brands appropriating something. They’re not committed to any genre. In the same way, most of the catwalk stuff that’s happened and the diffusion of that into places such as H&M is not aimed at metal fans. It’s aimed at people who want that look.

It’s interesting looking at where the appropriation journey ends. Because metal appropriates too. So, who can claim to have the genuine article, and where does it stop?

Like anyone who is into a more extreme subculture, Metalheads resist appropriation by anyone else. You have set yourself as being different by liking this thing, which for many years has been uncool, and you’ve probably been picked on for wearing your Metallica T-shirt. Suddenly people are wearing the T-shirt who don’t know the music. But everything appropriates now and I am interested in it because of the way culture works now, which is quite parasitic on other things. That might sound negative, but I’m not judging it, that’s just how it works. There is an endless sampling of things.

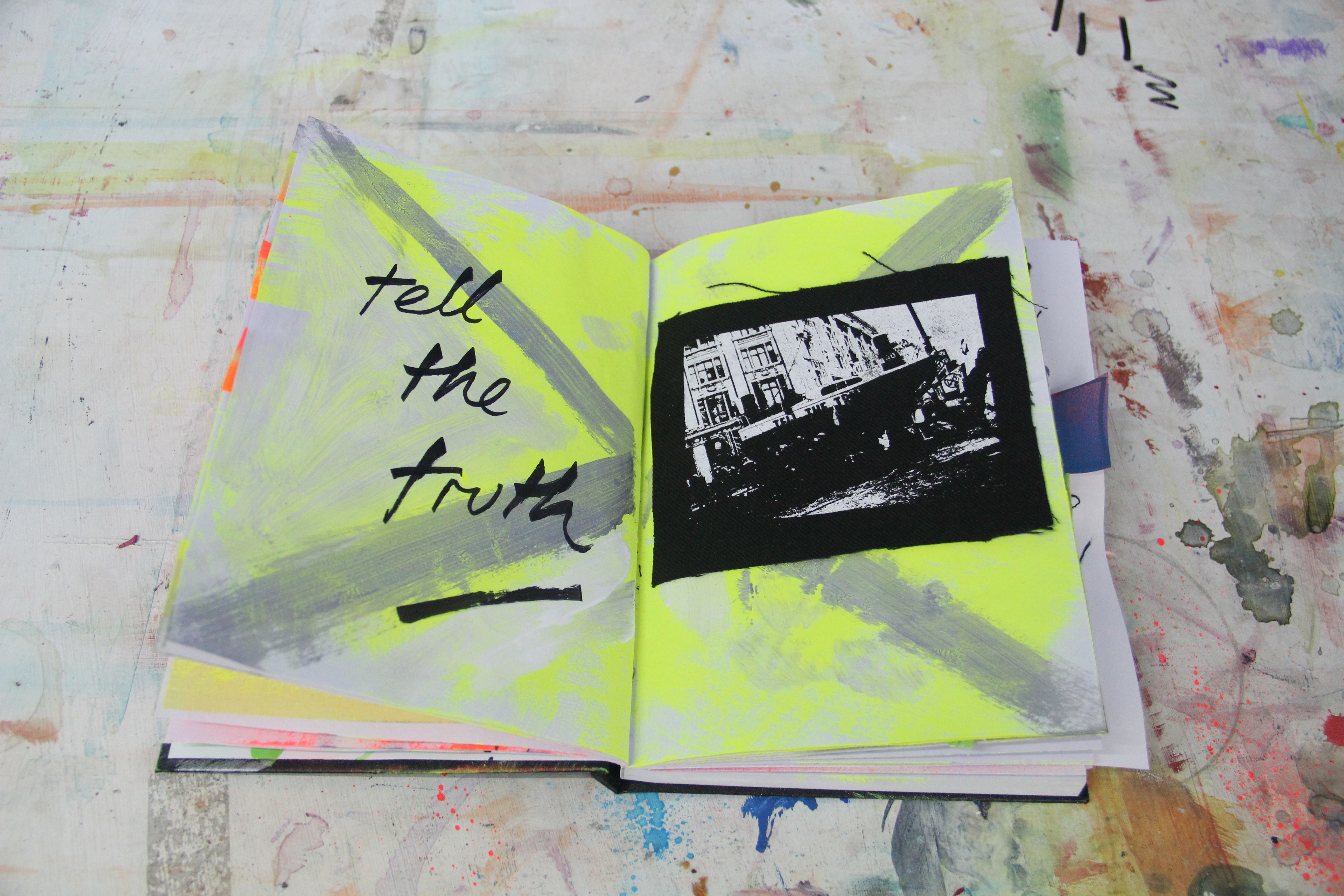

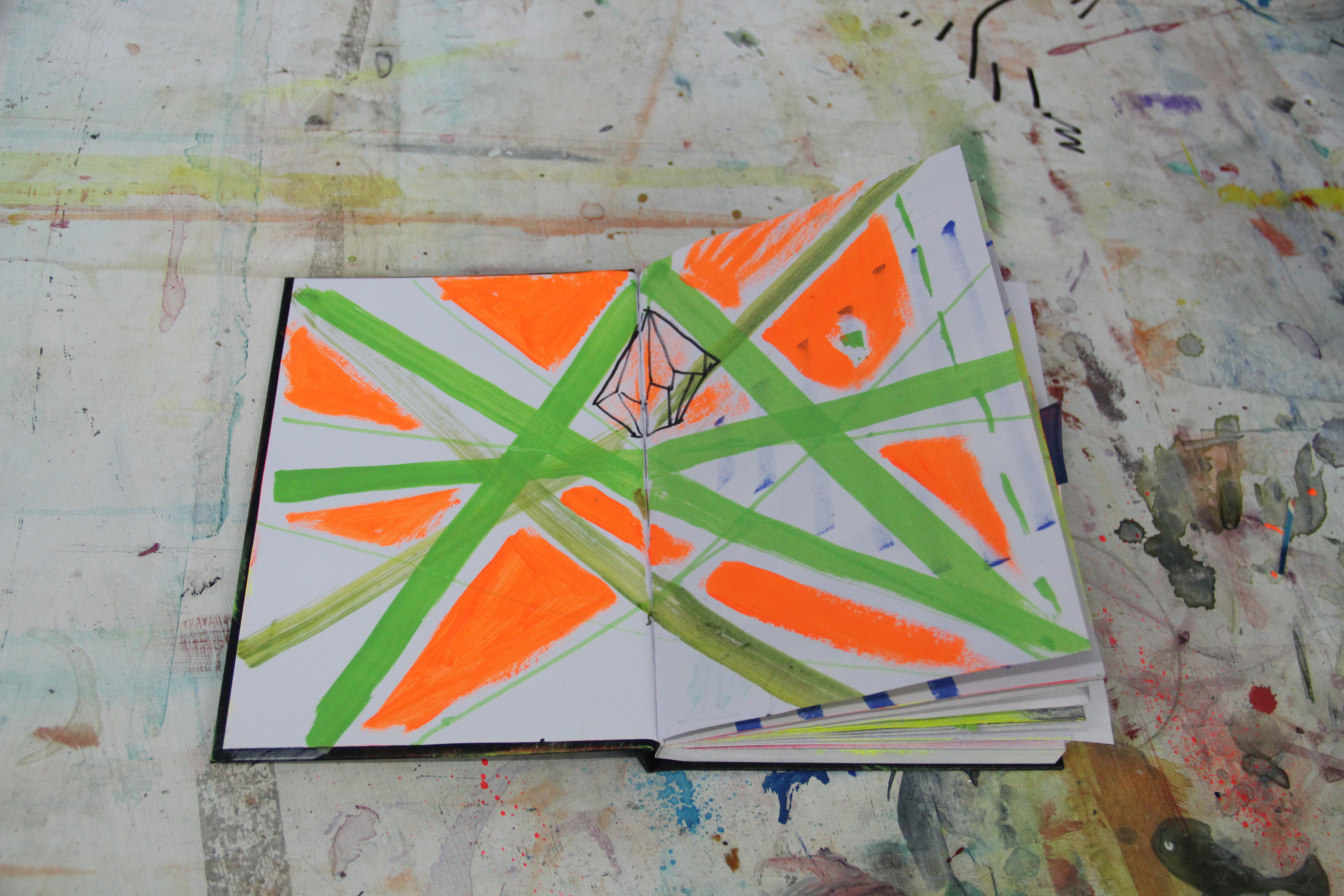

All artists-in-residence are invited to document their time at the Elephant Lab in a Winsor & Newton sketchbook, filling it with drawings, paint samples, odds-and-ends and other personal reflections. This is Tom Cardwell’s.

Residencies at Elephant Lab

Practising artists are invited to make proposals for a one month residency at Elephant Lab

APPLY NOW