What happens when your nation is suddenly at the centre of art world buzz? For Ghana, it’s a question that has become more and more pertinent. International attention has seen collectors acquiring works by emerging and established practitioners in recent years (aided by art fairs such as 1:54 and auction house support) and a growing, stable economy has led to major new culture and tourism investment, under the guidance of President Nana Akufo-Addo.

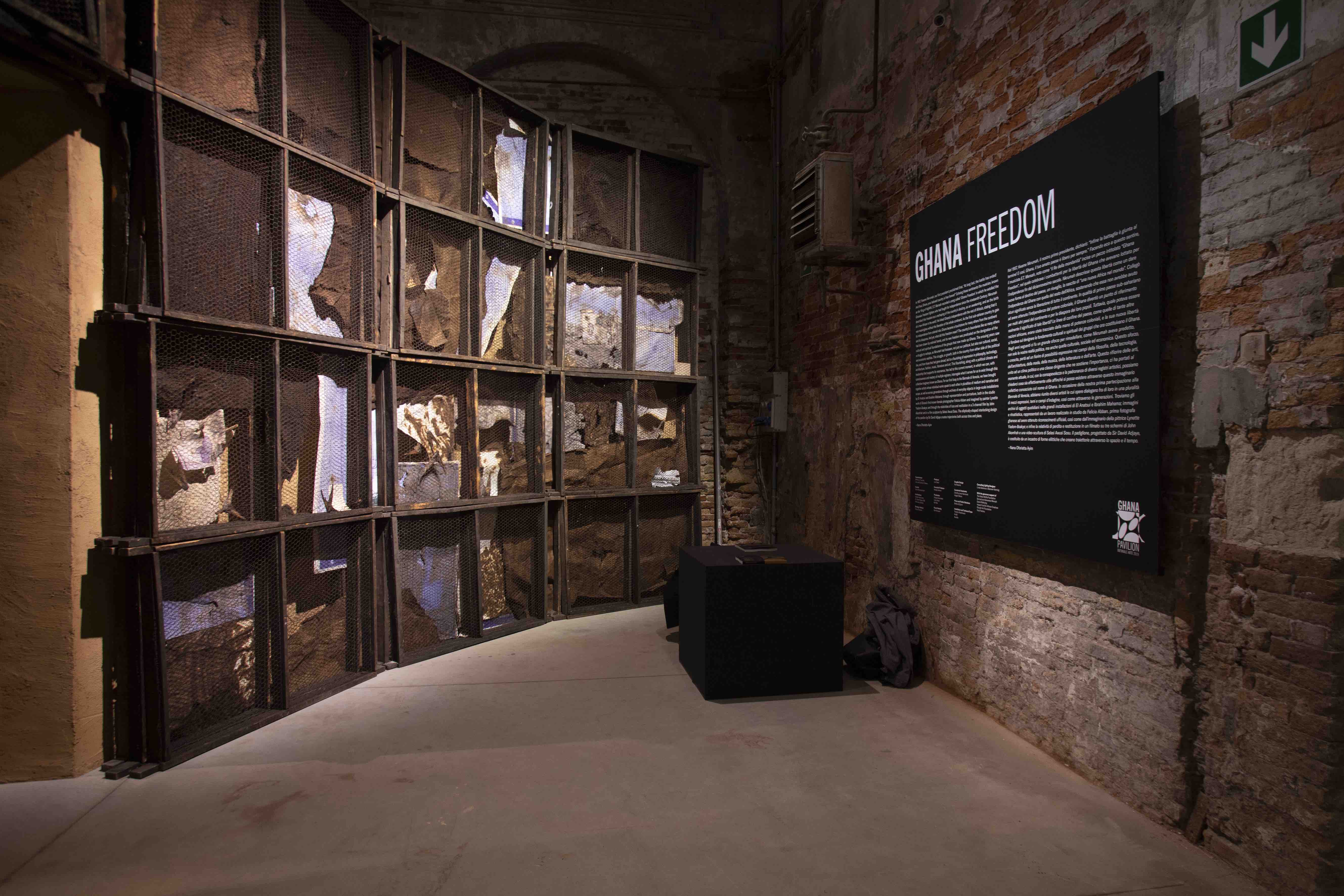

The tipping point seems to have come with the country’s inaugural pavilion the Venice Biennale, which was met with riotous acclaim by critics and the public alike, for its presentation of six artists hailing from their homeland and its diaspora. The cavernous space situated slap bang in the middle of the Arsenale was designed by David Adjaye, complete with earthen walls, and filled with Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings, major installations by Ibrahim Mahama and El Anatsui, film works from John Akomfrah and Selasi Awusi Sosu, and portraits from Felicia Abban, the nation’s first professional female photographer.

For curator Nana Oforiatta Ayim the pavilion has a clear purpose. “What the national pavilion has done most of all is resonate with what Ghana can be, and the idea of what art in Ghana can be, for the outside world. In Venice it’s as if you’re representing your nation outside of itself, it’s almost like a diplomatic exercise.”

This exercise has had visible government support and is clearly aligned with The Year of Return, a huge tourism initiative that marks 400 years since the first enslaved African arrived in Jamestown, Virginia. The year celebrates Pan-African resilience and encourages people from throughout the diaspora to embark on a birth-right journey. It forms part of a fifteen-year tourism plan that, according to CNN, seeks to increase the annual number of tourists to Ghana from one million to eight million per year by 2027.

This new cultural investment has been welcomed by some of those embedded in the Ghanaian art scene, who are more used to an independent approach to creative production due to a historic lack of government support, but that is not to say that all are in favour of financial resources being channelled into an international stage like Venice.

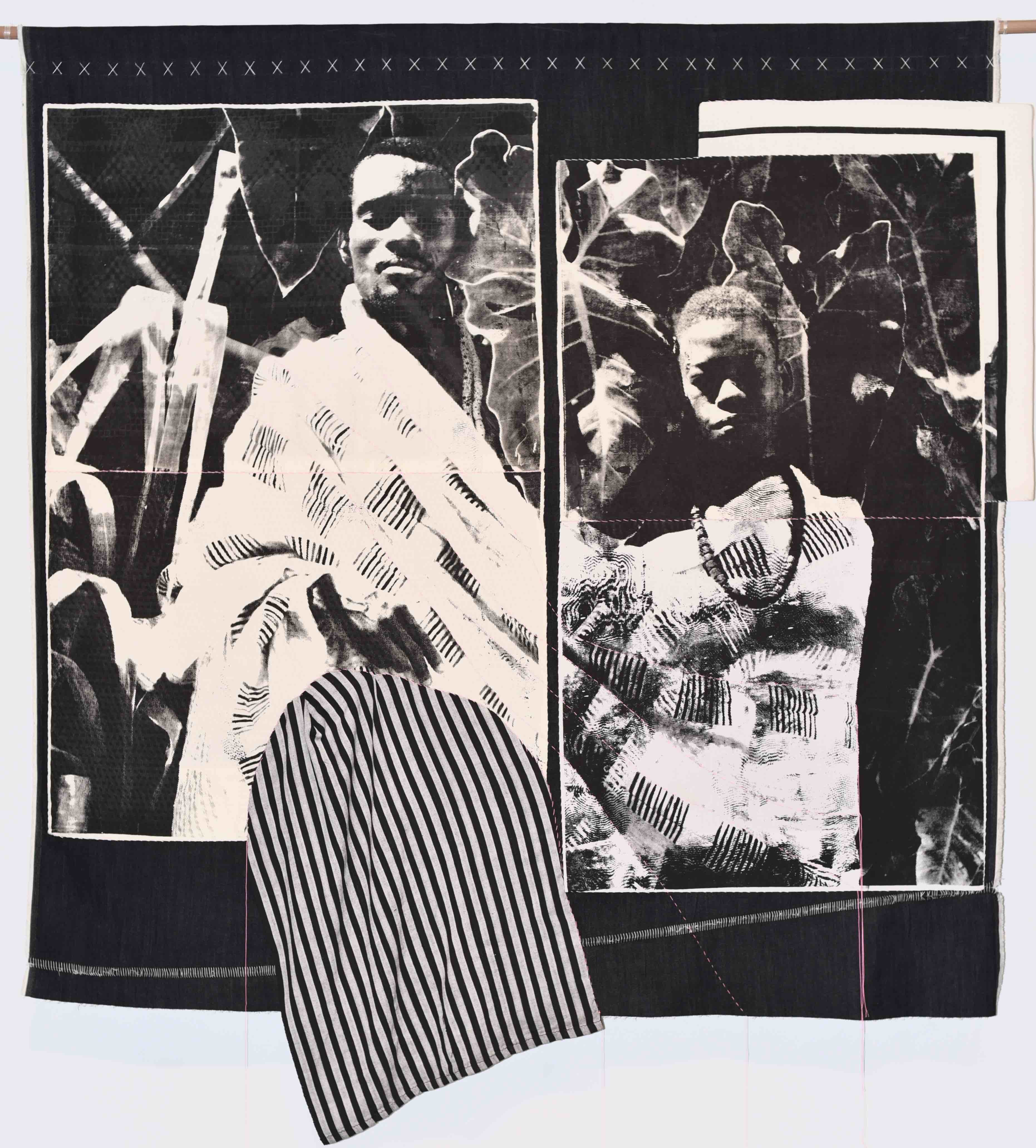

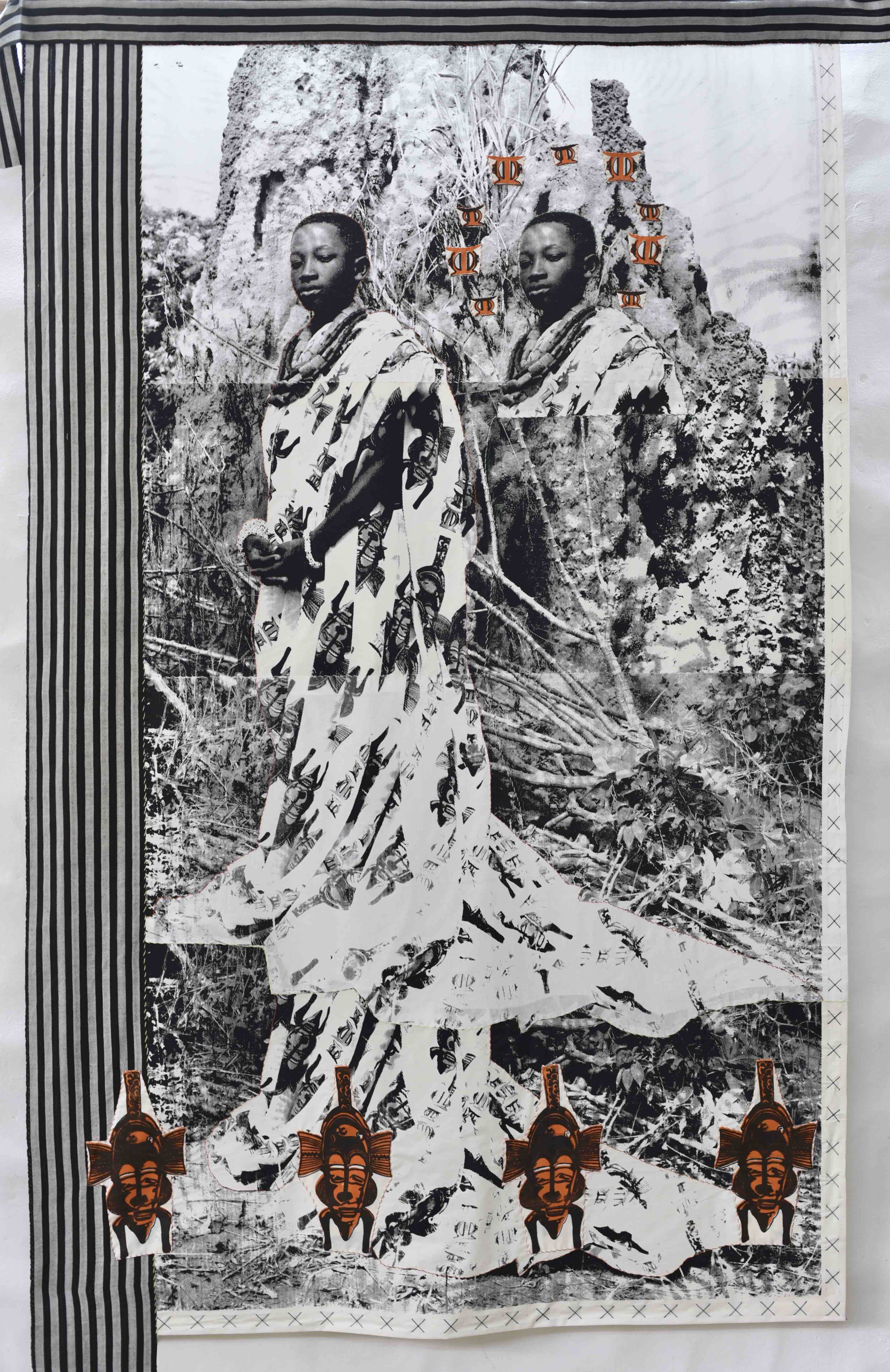

For German-Ghanaian artist Zohra Opoku, who is based in the nation’s capital of Accra, it would be better focused locally: “You have to ask, what have you done for the local art scene? How does it really go beyond this moment of visibility? There’s a lot of light on the pavilion and the makers, but there is very little on the current situation inside Ghana. If you come to visit you have a very different impression around the artists who are making things happen. I’m not thrilled about it.”

How the pavilion’s legacy plays out remains to be seen, but the fact that Oforiatta Ayim is already embarking on a touring programme that hopes to bring the ideas explored in Venice to wider audience, is promising. “In the next month we’re starting a mobile pavilion project,” she explains. “It will discuss some of the themes of Ghana Freedom, which will go on until November, then in December I’ll bring the exhibition from Venice to the National Museum of Ghana. We haven’t had government support in our lifetime, not since Kwame Nkrumah’s time. So, we have to ask, how can we use what happened at Venice as a spring board for other initiatives and for people to become a supporter of the arts? That’s a big challenge.”

The mobile project will hopefully build on an infrastructure that most refer to as “nascent” but is now rapidly gaining traction. First and foremost, the Chale Wote Street Art Festival, organized by Accra[dot]Alt, grows every year, and remains at the epicentre of cultural activity. With an emphasis on DIY practices and a commitment to “bringing art, music, dance and performance out of the galleries and onto the streets of James Town” the entire district becomes an infectious party for a week in August, where you’re just as likely to pick up some knock-off sunglasses as experience challenging, durational performance art from the likes of Crazinist Artist.

According to Oforiatta Ayim, “I think the Chale Wote festival has done a lot, because there’s a reason for people to come to Accra, and it’s a real Pan-African gathering. It really is the main thing that brings people together.”

But what of permanent institutions that offer access to art? The Nubuke Foundation in the East Legon district of Accra is the first place on many people’s lips, as it opens a reconceived permanent space later this year. For over a decade it has focused on scholarship and research relating to Ghanaian culture and heritage, as well as actively supporting Ghanaian artists.

Oforiatta Ayim’s own space, ANO, also seeks to offer a local context for art production: “When I first became aware of art in Ghana in my teens, the only spaces that were really offering art programmes were the foreign cultural institutions. I think people who set up organizations, including myself and Ibrahim [Mahama, who recently opened the artist-run Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art in Tamale] really felt that we needed our own space to offer a context in which we could represent ourselves and come together.”

This emphasis on the local community alludes to the less-than-positive results that can stem from an international audience suddenly encroaching on a burgeoning cultural scene, which is why many view the new attention as something of a double-edged sword. American entrepreneur Cheraé Robinson, who is currently based in New York and Accra, was sensitive to that when she set up Tastemakers Africa, a travel platform that focuses on offering a sustainable and conscientious tourism model that champions local talent and creativity.

“I felt there was no narrative about resilience or creativity —quite frankly anything celebrating the ‘cool’”

“Tastemakers Africa came out of a desire to see another narrative in African tourism, and one that is centred on the people that make the continent and the nations within it such an amazing place to visit. I felt there was no narrative about resilience or creativity —quite frankly anything celebrating the ‘cool’. Nothing was capturing the cultural movements and happenings and allowing visitors to tap into them in an easy way. There weren’t enough outlets for people to get their stories told, take their creative work and monetize it.”

- Courtesy Tastemakers Africa

The platform is currently live in Accra, as well as Cape Town and Johannesburg, with a focus on insider experiences led by locals. You can visit an artist’s studio, go on a street food tour, or learn about national heritage through architecture. “Accra is both where I spend the most time, and where we see the most bookings,” Robinson adds.

“A lot of our customers are American, and when they’re ready to make their first trip to Africa, it’s Ghana. That’s what we know culturally, the history and legacy of Nkrumah is part of it, but it’s also the welcome, the tradition, the modern and the contemporary. You see that in a lot of the artists that come out of the country, there’s a beautiful intersection of identity and future thinking.”

- Courtesy Tastemakers Africa

The overseas interest in Ghana, particularly Accra’s, cultural scene is undoubtedly growing, but as millennial expectations proliferate, with free Wi-Fi, flat whites and Airbnb assumed to be a standard, some offer a word of caution. “I have a friend who used to work in marketing for one of the big night life and restaurant groups in Accra,” says Robinson, “and on the one hand they’re excited that Ghana is on everyone’s list, but they did say ‘If everyone who has read all these news pieces actually shows up, we’re totally unprepared!’”

Above: © Zohra Opoku/ courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery; Below: Modupeola Fadugba, Dreams from the Deep End. Installation view at Gallery 1957, Accra (2018). Photo by Nii Odzenm © the artist. Courtesy Gallery 1957, Accra

Opoku shares a similar sentiment, especially as she has seen a huge uptake in overseas visitors to her studio. “There is an international movement looking at Ghana for sure, I can feel it. I have visits every week from other artists, museum curators and foundation directors, from across Africa, the US and Europe. I think so many people are making the pilgrimage, because they’ve got to know artists in museums, galleries and fairs outside of the country.” One prime example is Serge Attukwei Clottey, whose major installations formed from yellow jerry cans engulfed buildings in Labadi, and gained worldwide attention. He is represented by Gallery 1957, which Opoku refers to as the only commercial gallery that has had real international success, once again pointing to the fledgling scene.

“There is a real sense that the younger generation do not feel they have to leave”

Architect Alice Asafu-Adjaye has also seen a shift in the opportunities available for creatives in Ghana, which has led to a new state of mind for the younger generation. She studied abroad before working for Foster and Partners and Adjaye Associates, then relocated back to Accra and opened Mustard Architects, in 2015. “There is a real sense that the younger generation do not feel they have to leave. It used to be that everyone immediately went to the US, the UK, Germany and the Netherlands to study and work, if they were able, but now young people are starting their own businesses here. They might not be making a lot of money, but they’re doing it. It is a really exciting shift—they have no fear.”

Asafu-Adjaye also points to a renewed attitude towards architecture in Accra, which has had little domestic planning in recent times, despite an incredible history of modernism tied to the Nkrumah administration. “Until a few years ago all the houses looked like something you’d find in Texas. Everything was just built on a huge scale, as opposed to designed, but now people are seeing the value in working with an architect, to create something that responds to the environment, and feels truly Ghanaian.”

In-keeping with the new boom of entrepreneurs and creatives Mustard Architects has also worked on plenty of projects that include live/work spaces, bars and gyms, as well as ecologically-savvy systems. The practice has also worked on the refurbishment of the National Museum of Ghana in Accra. “I am involved in an ongoing project to bring the building back to what would be deemed an international standard, but I really wanted to respect the original design, which responds to its environment,” says Asafu-Adjaye. “It was built as part of the independence celebrations, but since then it had really fallen into a bit of a state. It has a domed roof and cross-ventilation but had since had air conditioning and all these other elements that didn’t function properly added on. I said, ‘You don’t need all of this, the building already works!’”

“We’re just lucky enough to have a constellation of people who are willing to put the work in”

Though Asafu-Adjaye admits that the project hasn’t been easy, it does symbolize a new page in the capital’s cultural history. She is also working with the museums board to conceive the new Door of Return monument that “has been conceptualized as a vehicle to reverse the ‘The Door of No Return’, the portal through which Africans were taken from slave castles, through the Middle Passage and onwards to the Americas.” It will be inaugurated in Fort Kormantin in Ghana, and the independent district of Accompong in Jamaica. “This kind of project is really a labour of love,” says Asafu-Adjaye. “It’s a chance to do something really special, and hopefully create a lasting legacy.”

- © Mustard Architects

To outsiders, this moment of international attention might seem as if it has sprung up out of nowhere, but Asafu-Adjaye knows different. “It is evidence that people have been working away quietly for a very long time.” Oforiatta Ayim agrees, “It’s just a lot of graft. People have asked ‘Why has Accra become so exciting?’ and the answer is that a lot of people from different corners are working really hard to make things happen. We’re just lucky enough to have a constellation of people who are willing to put the work in, and who are passionate and dedicated enough to do it.”