Arwa Haider, music editor at Elephant

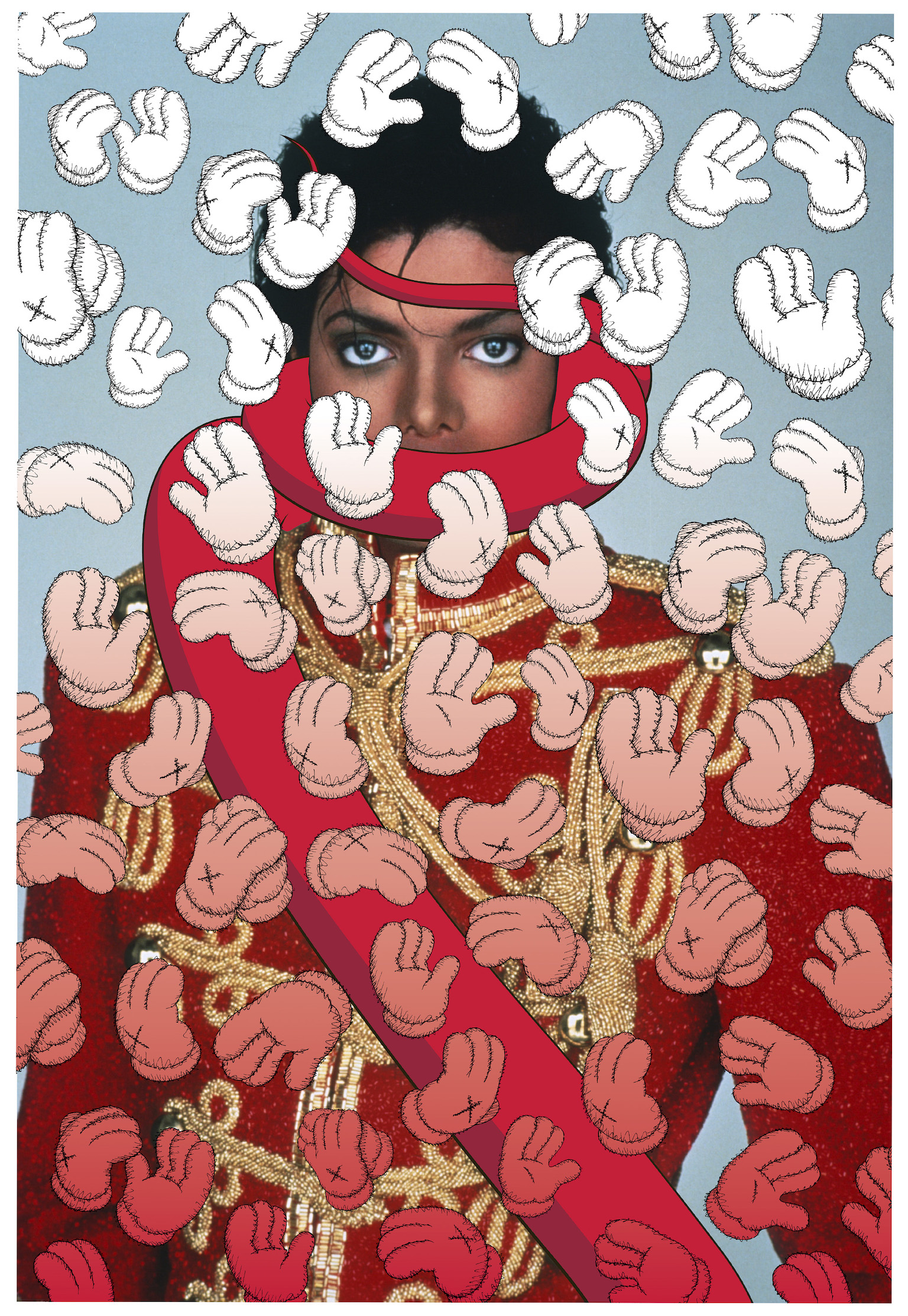

I’d nominate Michael Jackson: On The Wall at London’s National Portrait Gallery (now at Paris Grand Palais before travelling to Bonn). This is a really exceptional blockbuster exhibition, inspired by the most otherworldly pop culture icon, and with genuine heart and soul. It’s brilliantly imaginative in its scope—artists from Warhol and Haring to Kehinde Wiley were inspired by this legendary talent; Faith Ringgold and Todd Gray brought conscious and global perspectives—and fascinating inclusions include an avant-garde dinner suit designed by MJ himself. The musical fantasies make your spirit soar; the real life details make you weep.

Katya Tylevich, writer and co-author of My Life as a Work of Art

Los Angeles has had another good art year, and I could name several exhibitions worthy of being a favorite, but my knee-jerk, don’t-think-about-it answer is Ai Weiwei’s Life Cycle at The Marciano. Sunflower Seeds (2010) and Spouts (2015), in particular, echo the gravity of contemporary global crises, but are also quiet, poetic works, whose metaphors span any context.

Octavia Bright, writer and co-host of Literary Friction on NTS Radio

At the end of February, I arrived in Margate for a six month stint feeling adrift and a little spooked, and stumbled into At The Violet Hour, an exhibition that looked how I felt. A collection of installations and performances set against the crumbling glory of The Nayland Rock hotel, it was a surreal haunting of this once glamorous spot in which a host of artists (including Emma Critchley, Derek Jarman and Wolfgang Tillmans) recalled T.S Eliot’s The Waste Land. It was dark and witty and Lynchian in its energy, and has stayed with me all year like a mostly benevolent visitation, even following me back to London.

Eliel Jones, writer and curator

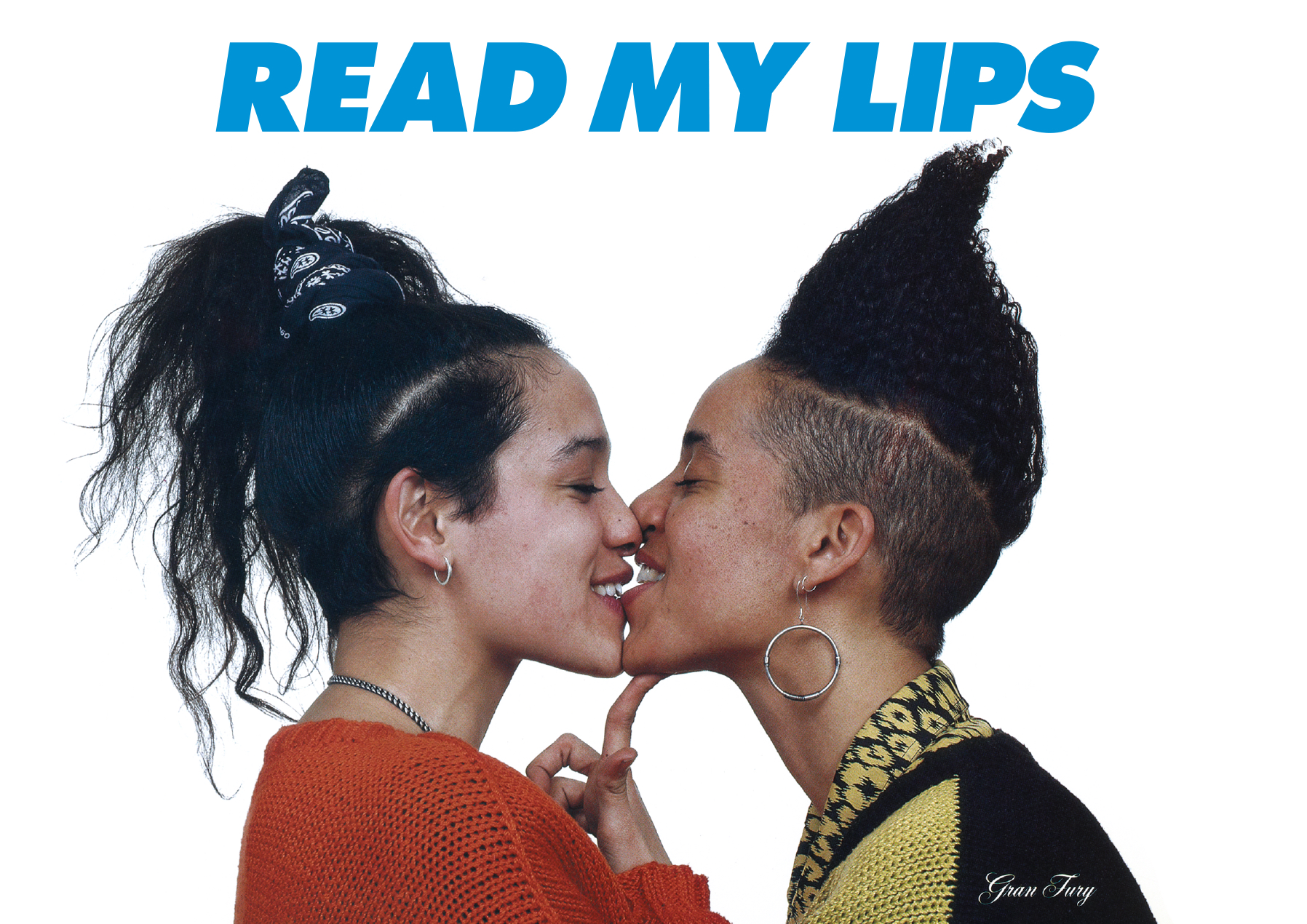

Auto Italia’s ambitious exhibition of work by the now defunct New York-based AIDS activist collective Gran Fury at Auto Italia in London was undoubtedly one of the most poignant shows this year. For many, it was an introduction to the radical work of the group who, between 1987 and 1995, helped reconfigure visibility and influence public consciousness surrounding Aids through provocative billboards and challenging demonstrations. In the current climate of constant and overwhelming crisis and social and political desensitization, Gran Fury’s embedded belief in the role of visual and performative languages to infiltrate discourse and to effect real change was a powerful reminder of what could be done today; through queer aesthetics, collective direct action, and a hell of a lot of fury, from Brexit, to #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter and, indeed, the continued issue of Aids beyond the West.

Paul Carey-Kent, writer and curator

Much as I’d like to choose something more surprising, it’s hard to look beyond Picasso 1932 – Love, Fame, Tragedy which bestrode Tate Modern from March to September: a well organised presentation of spectacular invention day to day, with a stream of masterpieces and stories to tell. In spite of which, I did have an issue with the exhibition. It presented 1932 as Picasso’s annus mirabilis, whereas I reckon it was one of many. I’d love the see the entire Tate filled with comparably scaled shows for each of ten such years spread out across his long life!

If I were allowed a second choice, incidentally, that would be equally clear. Covered in Time and History: The Films of Ana Mendieta at Berlin’s Gropius Bau filled six dark rooms with the remastered versions of twenty-three of her elemental and multi-layered films.

Charlotte Jansen, editor at large at Elephant

My choice is Nancy Spero at Museo Tamayo, Mexico City. “Little bed pal, lump of love” read one of Nancy Spero‘s works on paper from the late seventies, a collection of papyrus-like drawings scrawled and scratched with equal parts love and anger. Spero—co-founder of A.I.R, mother, artist, activist—is a shero of mine. Those words really stuck to me, so perfectly do they describe the winter, snuggled under the covers, with your loved ones, especially a small loved one, who I hold onto extra tight at night.

Elizabeth Fullerton, writer, critic and author of Artrage! The Story of the BritArt Revolution

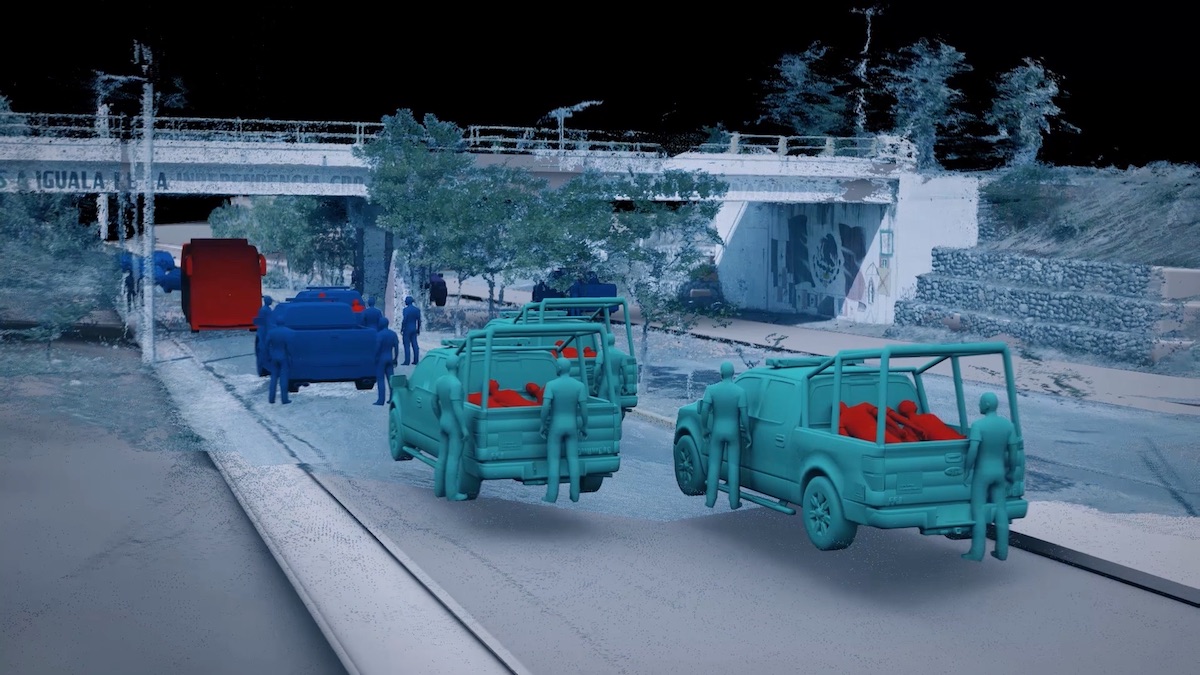

My favourite exhibition would probably be the ICA show Counter Investigations earlier this year of Forensic Architecture. The show blew me away, in part because it felt so fresh, spanning disciplines from law to journalism to architecture to activism, and you really got a sense of the urgency of their work. The displays about state-sanctioned killings and wrongdoing—whether migrants being left to die by EU military vessels or Israeli soldiers shooting at Palestinians with live bullets—were all the more shocking because they were real. Forensic Architecture presents each harrowing case like a detective story, methodically unravelling “official” versions of events.

One that stuck with me was their analysis of witness footage of a U.S. drone strike in Waziristan in Pakistan. Using 3D modelling, they traced the trajectory of shrapnel fragments on the interior walls of a home, concluding that where the shrapnel was less dense may mean that it was absorbed by human bodies before impact—the kind of information that is rarely legible in the video game-like images provided by governments. Forensic Architecture is challenging assumptions about what art is, and I found that really exciting.

Louise Benson, deputy editor at Elephant

It is often the exhibitions that you enter without any hype or preconceived expectations that most effectively blow you away. On a flying visit to Milan this year, I finally made it to the Fondazione Prada, that legendary OMA-designed playground and temple to the visual arts. To stumble upon a remarkable, expansive survey of art and culture in Italy in the interwar period was not something that I had anticipated; I marvelled as I walked through Post Zang Tumb Tuuum. Art Life Politics: Italia 1918–1943, conceived and curated by Germano Celant. Beautifully presented and intensely moving at times, the exhibition brought together not only works of art but social documents, magazine clippings and design objects. I was struck by how utterly contemporary many of the works on show felt, still radical even by today’s standards. I planned to spend only an hour or two at the Foundation, and instead found myself being shooed out at closing time. I almost missed my plane as a result of this exhibition, and I only wish that I could have returned for another look.

Robert Urquhart, design lecturer and editor at large at Elephant

I always enjoy visiting the Van Abbemuseum whenever I’m in Eindhoven, and this year I popped in while Dutch Design Week was on back in October. The space is fantastic and the exhibition GEO-DESIGN: Alibaba: From Here to Your Home, curated by Joseph Grima and Martina Muzi, saw the Design Academy Eindhoven collaborate with the museum on a topic that sounds deadly dull but was made fascinating by the duo and their raft of artists: China-based Alibaba, the world’s largest virtual shopping mall. It was everything a show should be: thought-provoking, visually dazzling and technically impressive. The show was a real education in power and the much-overused word “innovation”.

Ariella Wolens, writer and curator

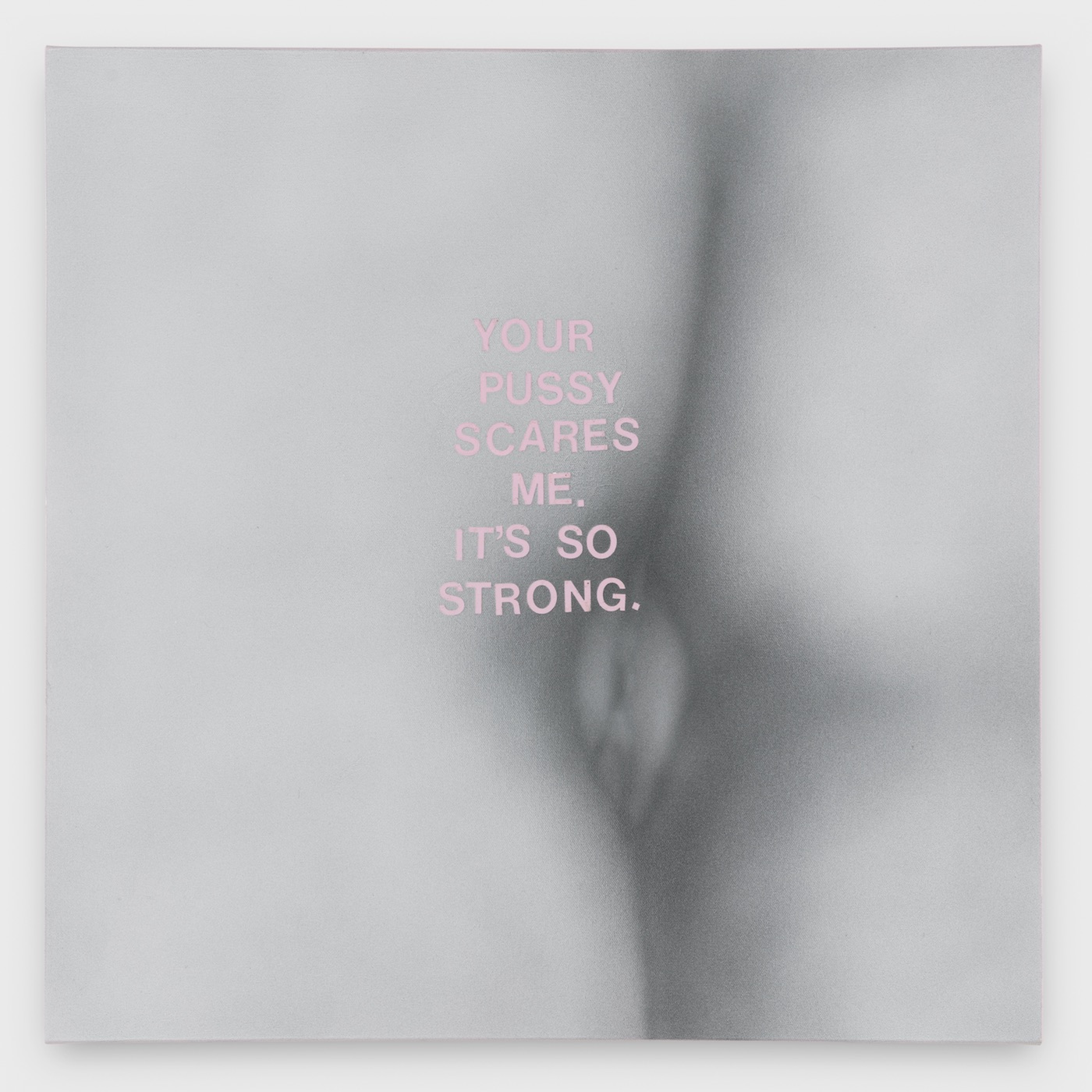

In a year that was plagued by the unearthing of staggering cases of brutality against women, it is fortifying to see someone make great art of great pain. Betty Tompkins—a renegade figure who has been challenging the definitions of what constitutes feminist art since the sixties—presented Will She Ever Shut Up?, a new body of work at PPOW this year in which she appropriated the trite apologies of some of #MeToo’s chief offenders and then painted these guilty pleas upon the bodies of female figures from some of art history’s most beloved images. Never before have classical nudes and portraits of noblewomen come alive with such force. In seeing Tompkins’ work, these allegorical figures and models become real women who have been shamed, abused and vilified. This show added a new element to Tompkins’ oeuvre which confirmed that despite being in her seventies, this artist’s creative force has far from diminished.

Jess Saxby, writer and translator

I saw Ana Mendieta’s Covered in Time and History, a collection of the artist’s film work, firstly at the Gropius Bau in Berlin, and then again in Paris at the Jeu de Paume. It provoked different patterns of thought each time, but both times set in motion some serious emotional stirrings. Whether it’s the nature of the medium, or the inescapable weight of the artist’s real life absence in the face of her projected image throughout the show, it was exhibition tinged with a weight of melancholy. There was so much to engage with—the violence of the female bodily experience, the notion of memory and effacement, the intertwinement of geography, topography and memory—you could spend a lifetime studying these video works.

I don’t know if this is cheating but I’d also like to name check Joëlle Tuerlinckx’s Les Constellations de Peut Être at the CIAP on Île Vassivière this summer and Gijs Milius’s painting show Le Long de Raduses at Galerie Catherine Bastide in Marseille this spring, because they were both shows that were totally brilliant in totally different ways.

Digby Warde-Aldam, writer and art critic

I have selected Harmony Korine: Blockbuster at Gagosian Gallery, New York. 2018 has been a singularly dispiriting year, and my choice reflects this. This show’s premise was a simple one: some time ago, the film director Harmony Korine bought up the entire stock of a VHS rental shop that had gone under, and set to work on the cassette covers with a paintbrush and palette knife. The result was a series of bizarre, swirling paintings that built on the imagery of everything from the Blues Brothers to The Blue Angel and echoed the berserk humour and scary psychedelia of Korine’s films. It sounds a bit silly perhaps, but the effect of seeing hundreds of vandalised video cases arranged in huge grids on the walls of Gagosian’s Upper West Side outpost was quite something; Korine’s anarchic handiwork went off like a bomb in these clinically tasteful surroundings, pure visual fun in a space that didn’t quite know how to cope with it. Blockbuster was not the most illuminating or intelligent exhibition I’ve seen in the last twelve months—actually, it might well have been the least illuminating and intelligent—but I honestly can’t think of anything else that made me smile as much as this did.

Emily Spicer, writer and critic

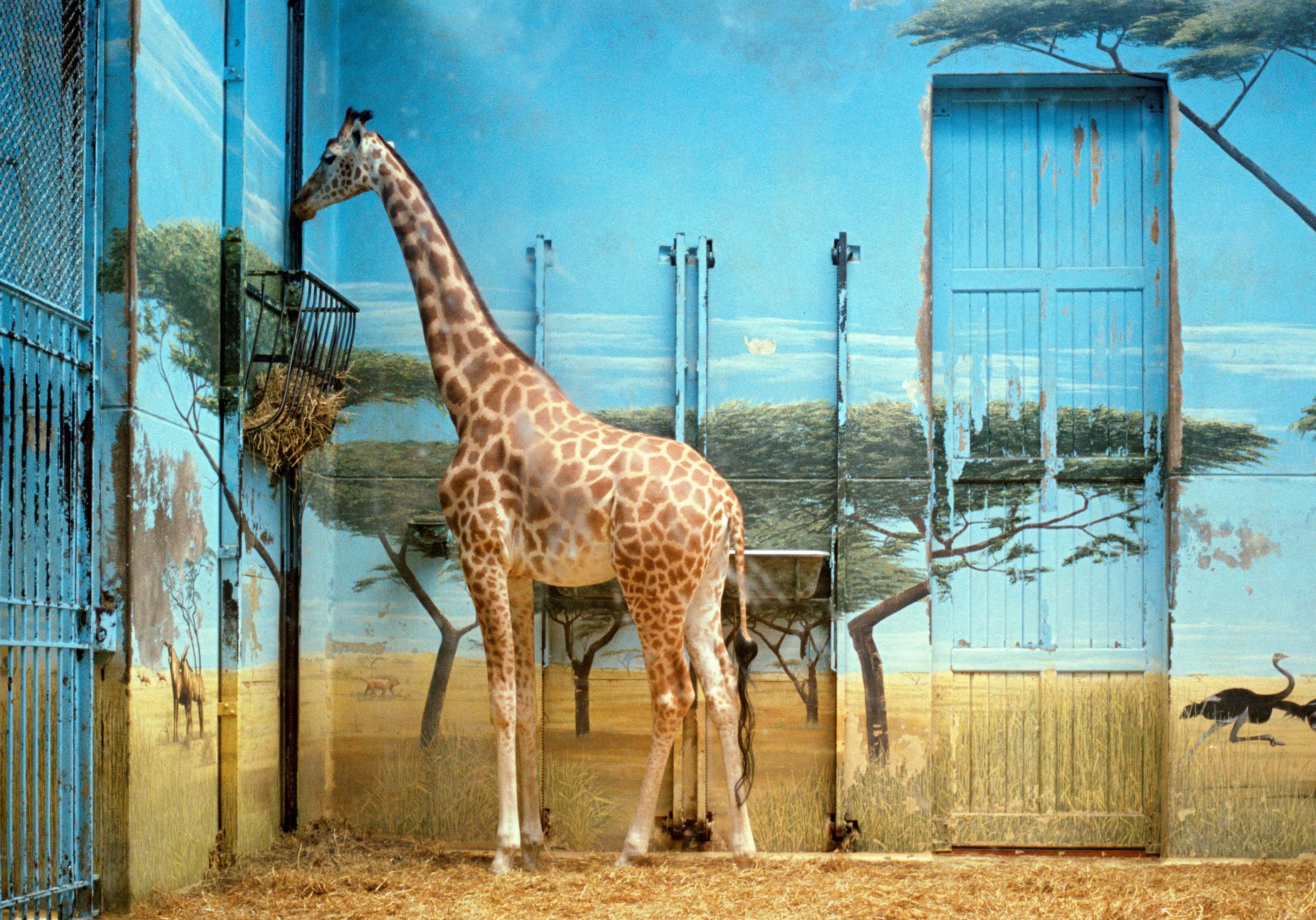

The group exhibition Animals and Us, which opened at Turner Contemporary in May, has stayed with me all year. I still think of Charlotte Dumas‘s photographs of the retired search and rescue dogs that so bravely attended the devastation of 9/11. The more I learn about animal behaviour, the more I think of humans as just another species, rather than in someway distinct from—or superior to—everything else. And having read about the curiosity and intelligence of octopuses, and their fondness for marbles, all tentacled animals remain permanently off the menu.

The dread march of 2018 has been tempered by a rich spread of exhibitions, from the serenely cruel video art of Ana Mendieta at the Gropius Bau to Manifesta 12’s rambunctious tour through Palermo’s crumbing palazzi. But to choose a single highlight, nothing compelled me as much as Bruegel at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. The most complete survey of the great Flemish painter ever convened, it was an eye-opening chance to discover his complete oeuvre, underpinned with meticulous research into his working methods. There were frolicking bears, infernal tortures, an encyclopaedic account of children’s games, and extraordinarily grandiose, rolling landscapes, all imbued with the exuberance of life.

Holly Black, editor at large at Elephant

More of a large-scale installation than an exhibition per se, Serge Attukwei Clottey’s incredible Afrogallonism project in Accra, Ghana, sees thousands of yellow plastic bottles (known locally as “Kufuor gallons”) cut up and fastened together to create gigantic plastic tapestries. When I visited his studio in Labadi his works had become something of a seismic yellow brick road, joined together to cover not only Clottey’s building but the surrounding streets. The work is made possible thanks to the help of the local community, who often assist in stitching pieces together or by recovering more bottles.

Emily Steer, editor at Elephant

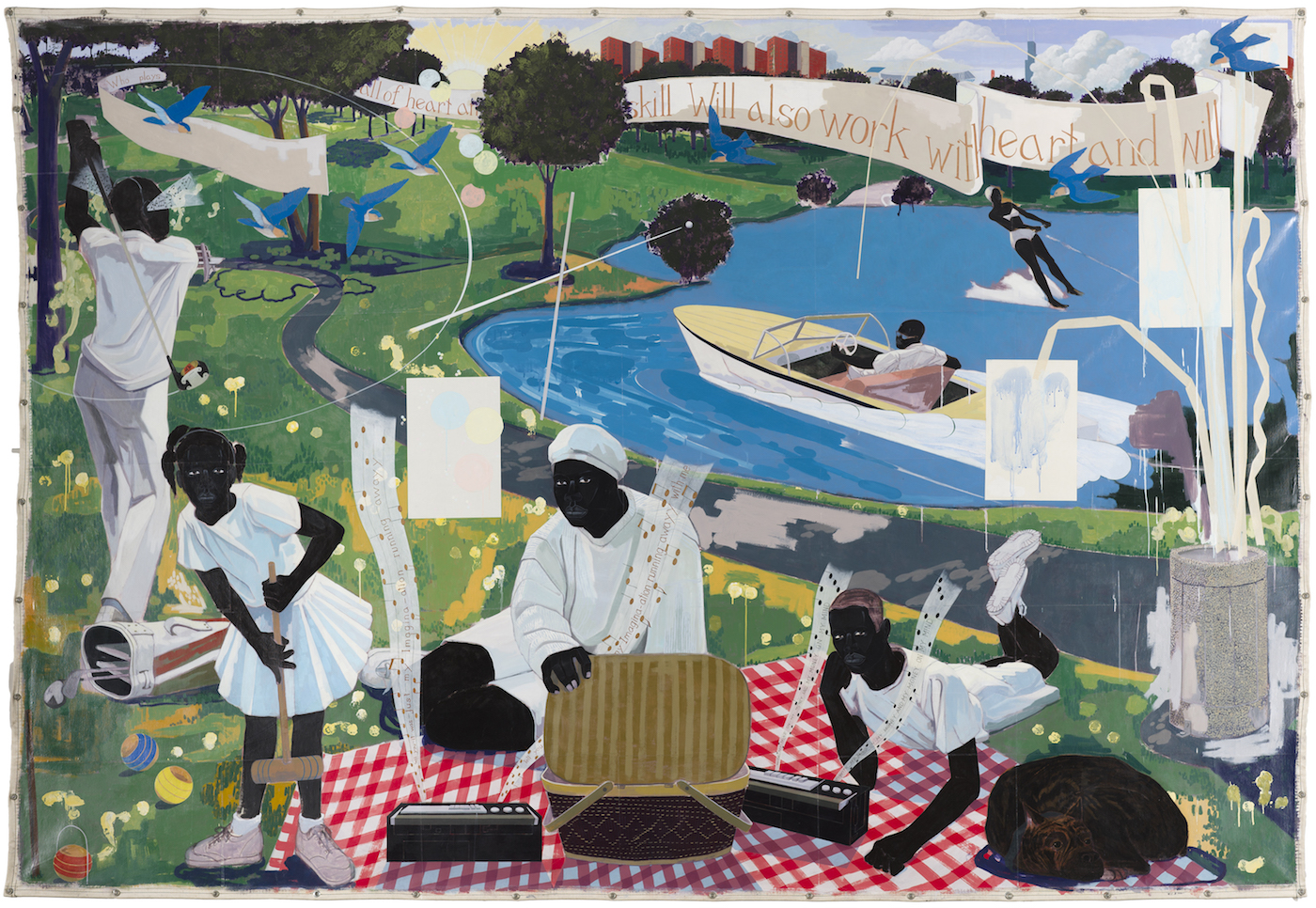

It’s been a powerful year for Kerry James Marshall. His 1997 painting Past Times was bought for $21.1m at auction—the record price for a black artist—by none other than Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs. He also had a terrific solo show, History of Painting at David Zwirner Gallery in London, which expanded upon and deviated from the portraits that I have been most familiar with, including paintings of price tags for other artist’s work, work title labels painted onto canvas and landscapes. His works always challenge the constraints of traditionally accepted art history, and this show really took its viewer behind the curtain. I’ve wanted to see his paintings in the flesh ever since we featured him in issue 29, and his level of technical prowess was even more spectacular than I imagined.

Muriel Zagha, writer and broadcaster

My favourite show this year was Fashioned From Nature at the V&A, a historical retrospective of the impact fashion design has had on nature over the last 400 years, from seventeenth-century silk embroidery to the technological innovations currently at play in the manufacture of trainers. This show could have felt finger-wagging and oppressively didactic: rather, it was intensely alluring and profoundly troubling in equal parts, like my personal highlight: a late nineteenth-century muslin dress embroidered with thousands of iridescent beetle wings, at once beautiful and repellent. The whole show opened avenues of thought about handmade luxury goods and the mass-produced, and also offered some ways for the fashion industry to reduce its carbon footprint.

Philomena Epps, writer and editor of Orlando

My favourite exhibition from 2018 would have to be Virginia Woolf: An Exhibition Inspired By Her Writings, curated by Laura Smith, at Tate St Ives. Although the show then toured to Pallant House Gallery and The Fitzwilliam Museum, it felt symbolic and powerful seeing the exhibition in Cornwall, where Woolf spent her childhood summer holidays (particularly as I was staying in a hotel which faced the eponymous Godrevy Lighthouse of her book). The exhibition traced a feminist lineage of female and non-binary artists—from 1850 to the present day—through the lens of Woolf’s influence, paying attention to themes of landscape, domesticity, gender, representation of the self, and identity. Despite the breadth of material (with over 250 works), the show managed to feel both intimate and capacious, focused yet generous, signifying the fluidity of these potential connections between the works. Space was also left for one’s own thoughts and feelings to crystallise, illustrating Woolf’s legacy in contemporary thought as a catalyst for thinking about a community—both tangible and imagined—of past, present, and future creatives

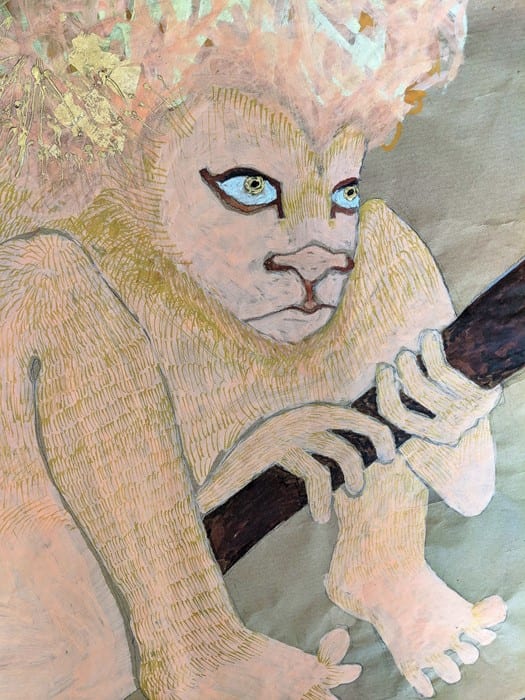

Jesse Darling, Lion in Wait for Jerome and His Medical Kit (detail), 2018 © Jesse Darling, courtesy the artist and Arcadia Missa

Hannah Gregory, writer and editor

The theological tale of Saint Jerome and the wounded lion provides a dual holding structure for the works of Jesse Darling’s first institutional solo show, The Ballad of Saint Jerome at Tate Britain. No saint but a Jerome by formation, I spent much of the year craving a soft creature beneath my desk and/or waiting for the fierce lion of the unconscious to speak. I asked that it be received kindly by the word-world: although the lion does not belong in language, it needs to find a place in which to be heard. Pens as swords, brandished readily; pens as amputated digits, writing impossibility. Hands poised in frail gestures, index fingers pointing at the erroneous ways of the West, and paws signing what can’t be read, only intuited. A correspondence of not-quite letters on lined paper, in which I see question marks, cryptic but from a me to a you.

Emily Gosling, editor at large at Elephant

Set in a church in Bethnal Green to mark the launch of Boiler Room’s 4:3 platform, Swimming with Arthur Russell was a beautiful tribute to the late musician, with pieces from Russell’s personal archives including sketches, photographers, letters and flyers, as well as video interviews. The stunning site-specific sound installation by Andy Stott united the joy of Russell’s disco years with the utterly heartbreaking, sparse songwriting to an effect that certainly made me shed more than a few tears.

Louisa Elderton, writer and editor

I have chosen Alice Morey: Shapes of Permanence at Lehman + Silva, Porto. Alice was one of the first artists I met when I moved to Berlin. Making the trip to Porto to see her exhibition of painting and sculpture was wonderful: abstract canvases inspired by natural forms and using organic materials from yoghurt cultures, spirilla and charcoal derived from wood gathered in the forests just north of Berlin to squirrel’s feet and mounds of rich, dark soil. Her powder pigments are pure and bright with pinks, oranges, blues, greens and yellows melting into one another. Morey’s world is sensual and joyous.