This week my fairly ancient but seemingly invincible Jack Russell terrier has been very ill. He somehow managed to get a horrific eye infection which for a short time looked likely to cost him his left eye, and possibly more. Luckily for both of us, he seems to be pulling through now. Whilst I’ve been at home looking after the poor little mite, I have been thinking about my fifteen-year relationship with him—and our relationship with animals in general. I grew up in the countryside, surrounded by animals (both domesticated and wild) and thought nothing of eating a pheasant handed to us by the local gamekeeper; these days I couldn’t feel further away from the source of my food and the only interaction I have with animals of any kind is the relationship I have with my dear dog. I wonder how this affects my state of mind… The thought of losing Murphy is almost unbearable, so perhaps I really am feeling the lack of animal neighbours.

Recently I’ve been hearing a lot of talk about “the move out of London” amongst the artistic community. It seems for those trying to maintain an art practice, whilst balancing home life and managing to stay afloat financially, London is not a friendly place to be anymore. Instead, several small towns along the south coast such as Margate, Hastings and Folkestone seem to be offering a cheaper alternative, where small clusters of ex-Londoners bring elements of city life with them and artistic communities slowly multiply. There are certainly indicators that cultural life is burgeoning in these places: Jerwood’s Hastings outpost opened in 2012, bringing world-class contemporary art to the small seaside town; Turner Contemporary opened in Margate in 2011, and is currently (coincidentally) showing an interesting group exhibition about the relationship between humans and animals with young superstar artists on the bill such as Cory Arcangel, Andy Holden and Marguerite Humeau.

Whilst it is terribly sad for our capital city to be losing its makers and artists, perhaps it’s not altogether a bad thing. London will always be a culturally vibrant metropolis (White City is the new cultural hotspot, kids: you heard it here first!), and maybe it’s better for our artists and creative minds to be more connected to nature in order to successfully nurture their creative energy. I certainly feel more in tune with my creativity when I’m outside of town, and always come back to London with a renewed sense of vigour after a weekend in the countryside.

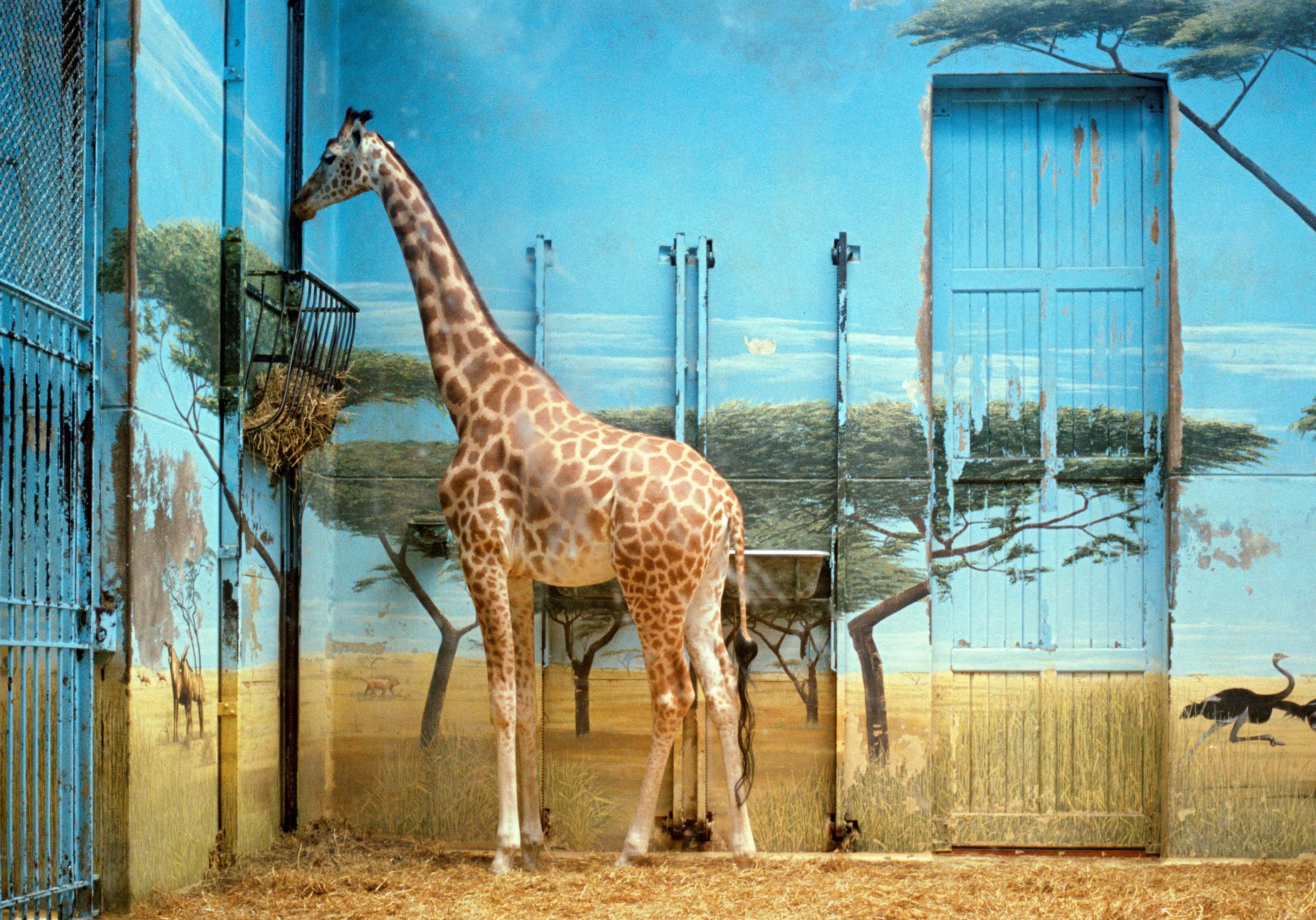

Living in a city as I have for the past twenty years, one does become very detached from the natural world and from the other creatures that inhabit the planet with us. Cities act as barriers to nature; all the concrete and tarmac an attempt to keep the “wilderness” at bay and preserve our manmade “civilization”. Only now are we beginning to wake up to the dreadful cost of disregarding the delicate balance of the planet’s ecosystems, and the enormous shift in worldwide human consciousness that must take place in order to save it from collapse. The problem seems to be that we have forgotten how to feel, and have instead replaced that sense with thinking; we are in our heads rather than our bodies, intellectualizing rather than intuiting. I’m interested in finding ways to reverse this situation, within the confines and strictures of our busy city lives.

I have been working with and supporting Anna Liber Lewis, a painter and winner of last year’s Griffin Art Prize (now the Elephant x Griffin Art Prize), for the past few months as she works towards a show at Elephant West in the early part of next year. She is working with a musician (full details to be revealed soon!) with the aim of creating an environment that encourages visitors to be in their bodies, feeling rather than thinking when experiencing the work. The idea is to give everyone “silent disco” headphones to listen to the music as they move around the space, looking at the paintings and feeling the intimate connection between the two. Anna wants to give the audience space and agency to feel, letting go (for a moment) of thoughts and anxieties, in order to really be in the space with the work.

Over the past few weeks we’ve been discussing ways of bringing other art forms into Elephant West, in a way that feels meaningful and active. We’ve had some very interesting initial conversations with the brilliant BalletBoyz (associate artists at Sadler’s Wells since 2005, amongst many other accolades) about creating improvised dance and movement in the space, either responding to the artwork or working directly with the artists to make something new and exciting. This feels like an area we can explore in an experimental way, and I’m interested to see how incorporating physical movement of bodies changes the dynamic of an art space; will it make it more accessible or less? Will it feel more welcoming or more confusing to the visitor? I’m hopeful it will encourage more feeling and less thinking.

A couple of weeks ago I was invited by Hannah Luxton, director of Glass Cloud, to join a panel of fierce and fabulous women to talk about “art in the public realm” at Camden People’s Theatre. It was a great evening, and we all had far more to talk about than the time allowed, but one part of the conversation that really stuck with me was a discussion about who we refer to when we use the term “the public”. The question felt very relevant to our ongoing discussions about how we want Elephant West to feel, and who our target audiences are. In truth, the space is for everyone, but we are also aware that there are several barriers (perceived as well as real) that we must try to remove in order to attract certain groups.

It’s no easy task, but I think we really have two main roles: first, to ensure we communicate as widely and indiscriminately as humanly possible, and that the communication is clear, unpretentious and acts as a friendly invitation. Second, we need to ensure that every single person who walks through the door feels welcome and leaves with the feeling that they want to come back again sometime, whether that is to experience the artwork, watch a film, dance to the music or drink a coffee. As long as you feel something real when you’re with us, then I will believe we are doing our job right.