Chinese silk paintings from the Song dynasty and the work of Jean-Léon Gérôme and Pieter Bruegel are just some of the influences Edward del Rosario cites. You would never have guessed the names looking at his work, but once you know them, they make sense. There’s the technical panache and space you find in the Chinese paintings, the sharpness of Gérôme, and the crafting of colour as in Bruegel.

Chinese silk paintings from the Song dynasty and the work of Jean-Léon Gérôme and Pieter Bruegel are just some of the influences Edward del Rosario cites. You would never have guessed the names looking at his work, but once you know them, they make sense. There’s the technical panache and space you find in the Chinese paintings, the sharpness of Gérôme, and the crafting of colour as in Bruegel.

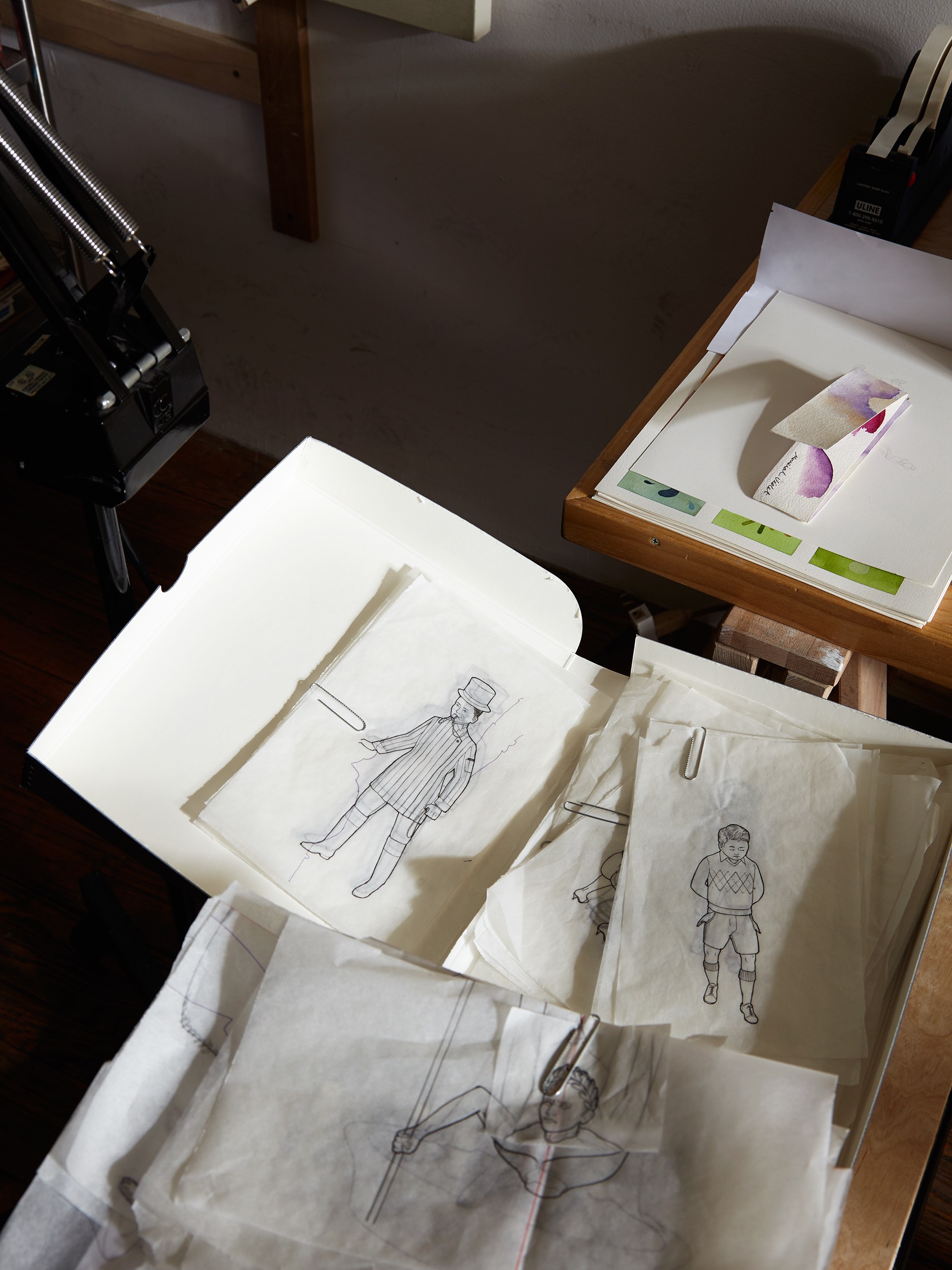

Using fine brushes on linen, Del Rosario’s work is like his studio: tidy, structured, and full of possibilities. In a way, all of the New York-based artist’s works belong to a society he has created, like a medieval “Sims”, and he is the puppeteer as much as the painter.

What is a typical day in the studio like for you? If there is such a thing…

An ideal day is twelve solid hours spent painting or drawing, not including breaks. A typical day is a meager attempt at making the day ideal. It takes me a while to warm up and begin painting but I find that I need this idle time to gather my thoughts and visually digest the work. I paint more efficiently and focused once I have had time to settle in. I work best at night and I like to end the work day around 2am. I try to start my day by 10am the next day. I suppose “warm-up” could be a euphemism for procrastination.

When and why did you take this studio? What do you like about working here?

I took this studio in the fall of 2015 because it happened to be available when I needed one. I was moving back to Brooklyn after a three-year break in New Hampshire. Finding studio space in New York can be an epic quest and this space opened up at a convenient time. The studio is expensive, has bad lighting and funny smells. It often sounds like I am working underneath a sports bar. However, I like that it is my own private space and that I can have solace in a building and borough swirling with activity.

What is essential for you in your environment when you’re creating?

Order. I need a clean, well-organized space to begin working. If things are out of place or if my studio is dirty, I have trouble getting started.

You can see that in your paintings to a certain extent! Something in the neatness and balance in their composition. What’s your biggest distraction when you’re in the studio?

The clock. If I feel that I have a limited amount of time to accomplish something, I am less focused. I need to have a large block of time available so that I don’t have to worry about watching the clock.

Do you always come in to the studio with a purpose or specific idea of what you want to get done?

No. I just come to the studio hoping to spend twelve hours working on one thing or another.

How and when did you get into painting your small figures—perhaps what you’re best known for?

I started painting small figures during my last semester of graduate school. I had been working with video and live performance pieces but didn’t have the resources to fully execute the productions I had in mind. I started drawing sketches and storyboards of the performances and these eventually evolved into paintings. In the end I found painting to be much more manageable than creating theater pieces. I didn’t have to depend on anyone else to create my vision and I could work with a limited budget.

Each figure in your paintings seems to have their own personality and intimate story, and together they create more narratives. Where did these stories come from, and have they changed or evolved over time?

The stories are autobiographical in nature, but not quite an autobiography. They are interpretations of anecdotes, fables, and real-world experiences from my childhood, a type of visual allegory of the post post-colonial world that I grew up in. Over time, the stories themselves have become a source material. Newer paintings refer back to older works and re-interpret the allegories contained within them. I think of the evolution as a type of visual tradition, similar in concept to oral tradition. Subsequent editions of painting become the editors of history, retelling the narrative but choosing which parts to emphasize, omit, or reinterpret.

There’s a great variety of clothing in your works too; what’s the function of dress and costume in your work?

I like creating work that is accessible on a variety of levels. The costumes are part of a system but I don’t want to require the viewer to “decode” the system in order to appreciate the painting. I like leaving the door open to a more in-depth inquiry into the subject matter, but I don’t like asking the viewer anything more than to “take a look.”

How do you feel about your works being called cute?

I’m not sure. Is the person using “cute” as an insult? I think there are definitely parts of some of my paintings that could be described like that, in the same way that parts of a Lisa Yuskavage painting could be described as “cute.” However, I don’t think that it is the defining characteristic. It is one of many elements I would use to convey a feeling.

“Truthfully, I don’t know what my life would be like if I hadn’t been pushed down the stairs.”

There was an incident that occurred when you were two years old that seems like it has informed a lot of the dramatic feeling in your work.

I don’t really recall the incident first hand. My mother told me that a childhood friend had pushed me down the stairs. I included it in my bio mostly because it sounded dramatic and life changing but also to be a little silly. Truthfully, I don’t know what my life would be like if I hadn’t been pushed down the stairs. Maybe my mother was kidding about the whole thing.

You can see elements of the theatre, and history, in your work—both forms of storytelling in their own right.

One thing I find fascinating about great theater is its ability to render the stage invisible—being so entranced by the performance that the artifice disappears. I would like to achieve this in painting. One should be well informed of history if you wish to create commentary of historical events. I am especially interested in the history (and continued effects) of colonialism and post-colonialism but I admit that I am woefully ill-informed.

You’ve also created work for some major publications; do you enjoy working with art directors?

It depends on the art directors. One great thing about working with art directors for major US magazines is that they usually give the artists a lot of freedom. Perhaps on account of their experience they find that allowing artists to exercise their best judgment produces the best work. Art directors that micro-manage are more challenging to work with.

What are you working on in the studio right now?

I’m in the process of animating some of my work. I’ve had this project in mind for some time and have started to experiment with some simple animated scenarios. Digital tools have simplified the process and bringing my work to “life” seems like logical loop back to satisfying my interests in theater and “live” action.

Images © Tim Smyth