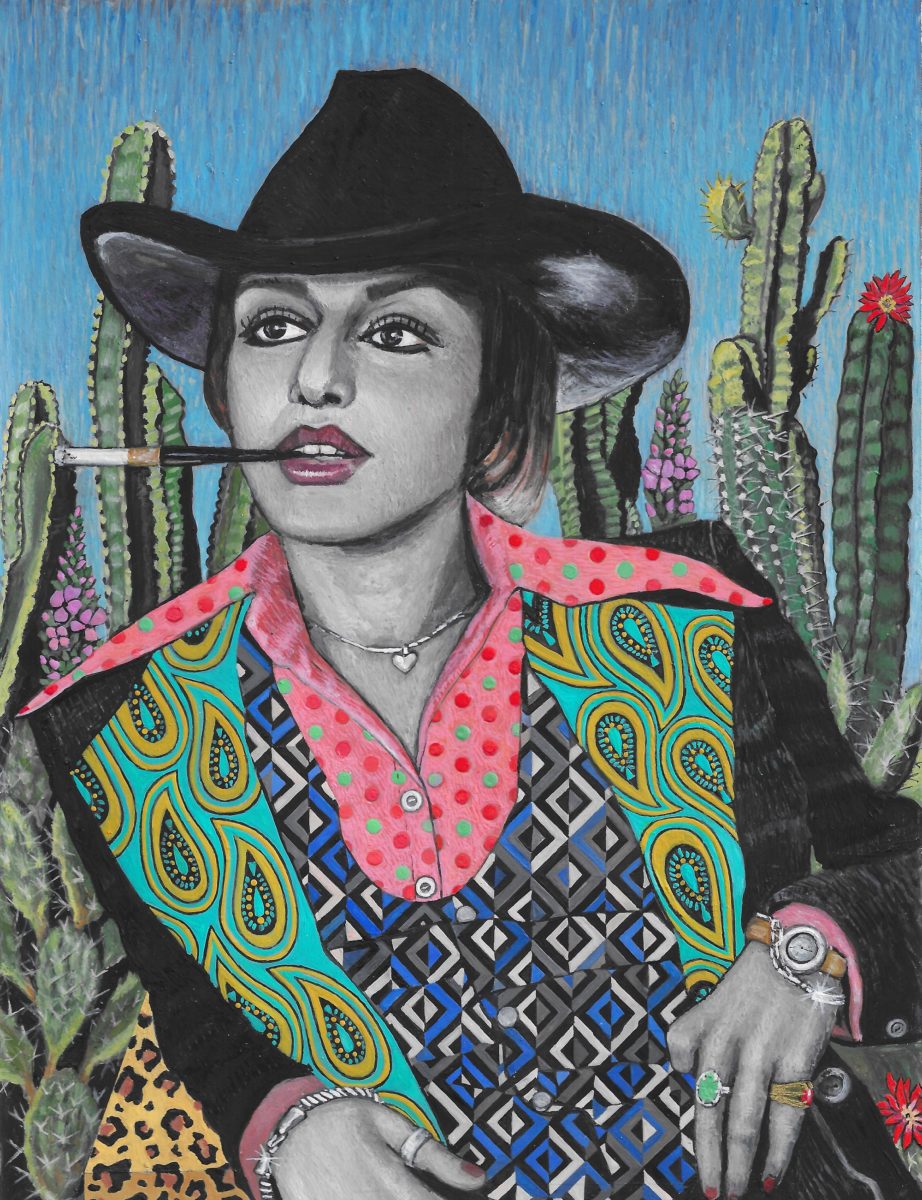

Walking through Soheila Sokhanvari’s latest exhibition of paintings at London’s Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, I feel as though I have been transported back in time. The walls are plastered with psychedelic prints, images of guns shooting red and white zigzags, and doe-eyed women wearing cowboy hats. As seductive as this stylized aesthetic may seem, it is the work of a complex artistic, cultural and historical collage.

Walking through Soheila Sokhanvari’s latest exhibition of paintings at London’s Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, I feel as though I have been transported back in time. The walls are plastered with psychedelic prints, images of guns shooting red and white zigzags, and doe-eyed women wearing cowboy hats. As seductive as this stylized aesthetic may seem, it is the work of a complex artistic, cultural and historical collage.

We meet in a cafe opposite the gallery in Wandsworth, where Sokhanvari insists on buying us both cakes. Her hair is dyed a deep purple and she speaks softly, barely above a whisper, but every answer is sharply constructed. Born in the city of Shiraz in Iran, Sokhanvari left for the UK in 1978 to study and has lived here ever since, returning to her home country only twice. Her exile was a choice rather than a necessity, but the impact of her cultural separation reverberates through her artistic practice in terms of both style and content.

“I feel as if my story is stuck in 1978,” she admits, “and because I am continually addressing that time in my work, I need to use a particular visual language, particular patterns. Patterns are political, they can speak about an era, or social status. For me, pattern is how we subconsciously judge each other and locate time, but there’s also a psychological aspect because patterns give us an emotional attachment to objects.”

“The patterns become not just a marker of time, but also visual memories of a very real and personal world”

Many of the patterns used in this particular series of portraits are taken from Sokhanvari’s father’s own designs, which were created for his fashion line in Iran. The artist’s choice to use the same patterns that surrounded her in her childhood is perhaps only natural, but it is also revealing of an intimate connection with her cultural heritage and the subject matter. The patterns used in her body of work become not just markers of time, but also visual memories

of a very real and personal world. And then there’s the fact that her latest portraits are re-imaginings of Iran’s forgotten female stars. Once at the centre of the country’s pop culture, these women were forced into exile or to abandon their art after the revolution of 1979 radically changed the country’s culture.

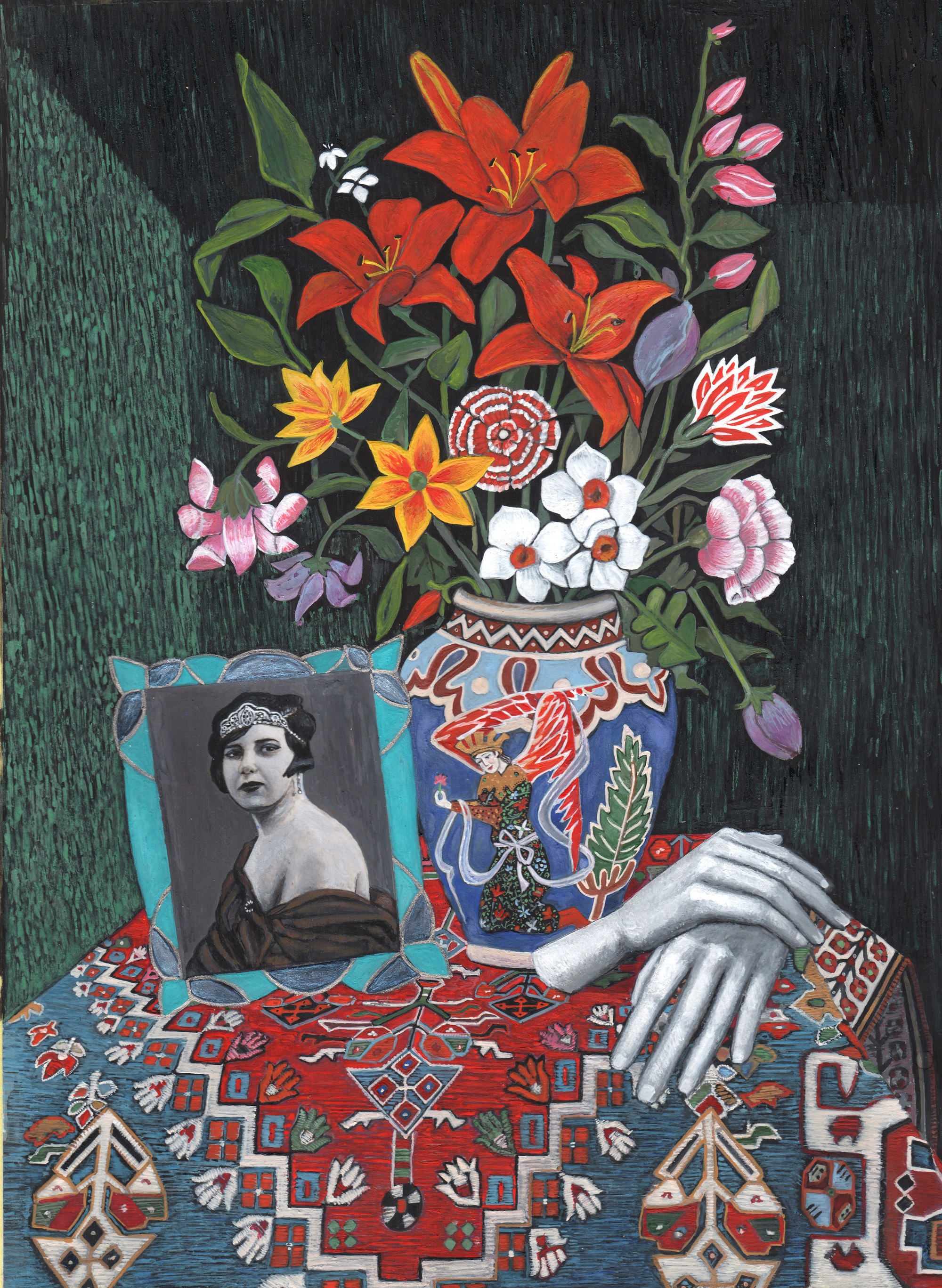

“Some of the women predate me, but Qamar-ol-Moluk Vaziri, for example, was someone my father and grandfather listened to, so I was used to hearing her songs,” Sokhanvari says. Significantly, Qamar-ol-Moluk-Vaziri is the only woman Sokhanvari has painted as an image within an image. The work is suggestively titled Still, Life—and the comma hints at a more complex narrative in which the artist subverts the still life tradition to highlight the singer’s transcendence across time through her own art form. Alongside her likeness sits a pair of human hands folded in a pose of submission or patience. While their meaning is enigmatic, they are perhaps most effective as symbols of Sokhanvari’s visual world in which realms of fantasy and reality not only coexist, but merge. Dubbed “the Queen of Persian music”, Qamar-ol-Moluk Vaziri was the first woman known to sing in public in Iran without wearing a veil, whilst the other women in the series were similarly pioneering in their respective art forms, some for simply persisting.

“A lot of these women actually came from very conservative Islamic backgrounds, and they wanted to make a leap into the space of Western art, but it wasn’t easy for them. They had to negotiate their culture, their family, and the men who dominated the entertainment industry at that time,” Sokhanvari explains. The portraits themselves are based on actual photographs, and whilst the artist has replicated the likeness to an extent, she also worked to reduce the male gaze by lifting them into otherworldly spaces in which they are simultaneously liberated and objectified through another form of artistic representation. It is an important tension, and one that the artist consciously builds into her practice in an effort to “negotiate the same line” as the women who were viewed as objects, while actively asserting the right to their bodies. This is not, of course, an issue in Iranian culture alone, but speaks of the social position of women globally and historically.

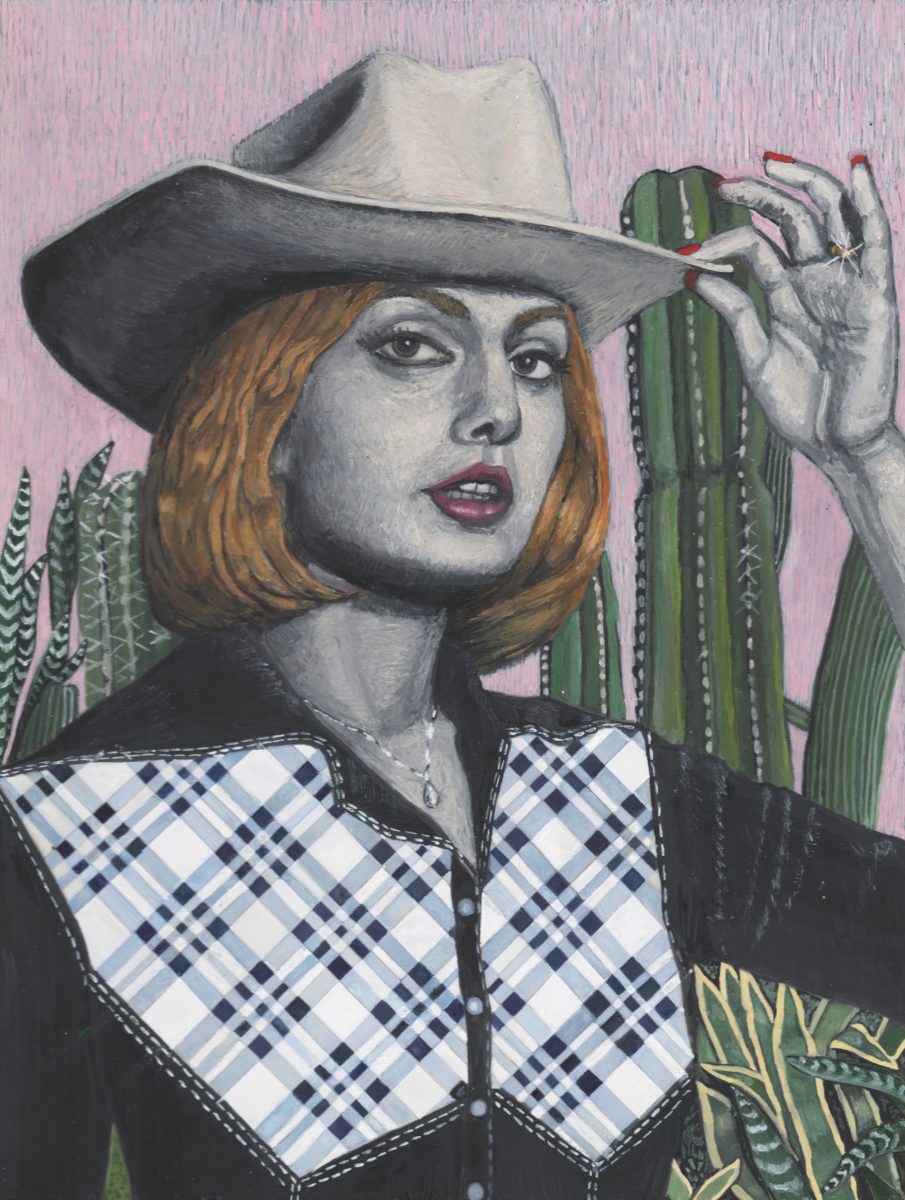

“Magical realism is a language that a lot of Iranian artists use to talk about forbidden topics,” she says. “By allowing real and magic to live side by side, there’s a slippage in meaning.” Humour possesses a similar function in the work; charming the viewer whilst pointing at some hidden truth. This is perhaps most obvious in the artwork Rebel, Rebel, which depicts the actor/singer Googoosh tilting her cowboy hat at the viewer, whilst phallic cacti rise up behind her. The title is imbued with mischief, and Googoosh’s flirtatious pose suggests a liberated self-awareness. At the same time, however, the looming, albeit symbolic male presence nods towards the more sinister reality in which women’s identities were, and continue to be, shaped for and by male consumers.

“Magical realism is a language that a lot of Iranian artists use to talk about forbidden topics. There’s a slippage in meaning”

Even the seemingly archaic medium of paint becomes a form of resistance and rebellion as Sokhanvari refuses manufactured materials, and instead mixes egg yolk with high-grade pigments. In place of canvas, she uses calf vellum, a material that not only lasts longer, but possesses connotations of religious sacrifice. Who or what is being sacrificed, you might ask, when these women are already figures of the past? Here lies the real crux of the artist’s preoccupation, which relates to what she terms as “historical amnesia”, in which a culture experiences collective memory loss due to a traumatic act in the past. “Amnesia,” she explains, “leads to folklore and myth,” or in other words, to the elaboration and blurring of truth or reality. These were real women, yes, but they are also the symbols of a forgotten time, not just for Iran but for those standing on the outside and looking in.