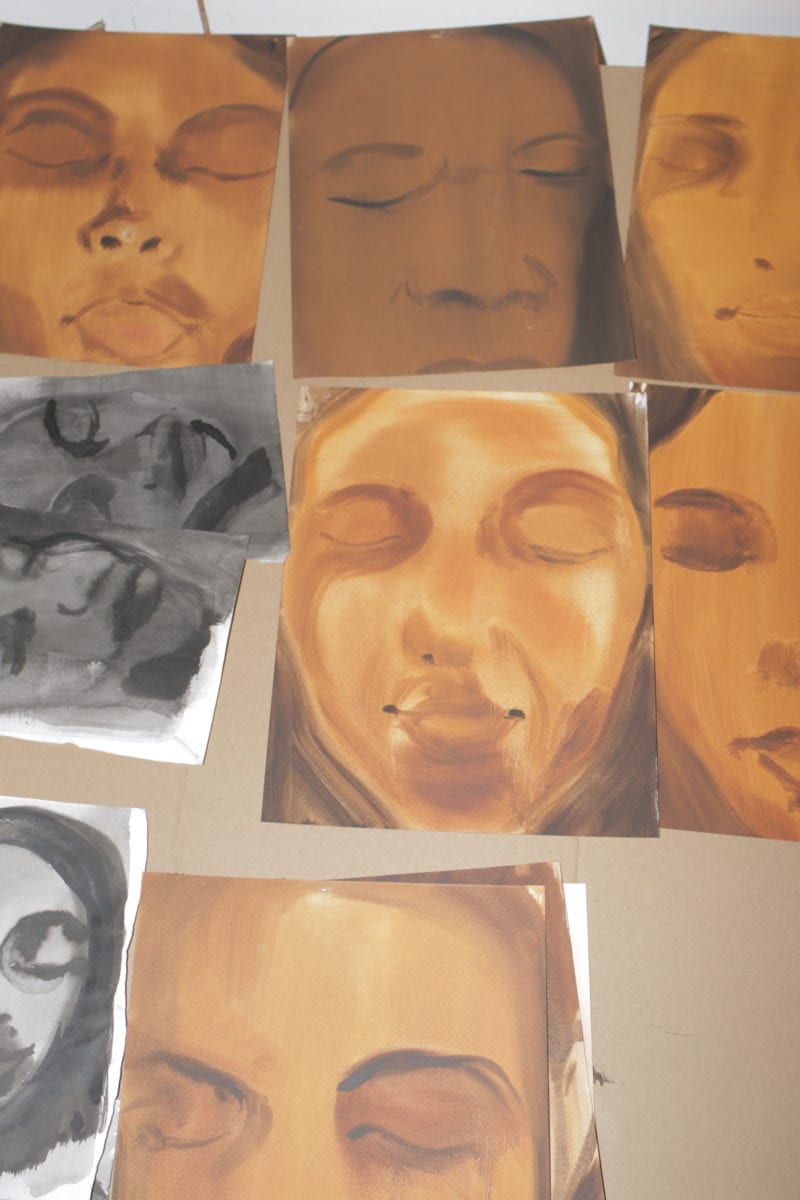

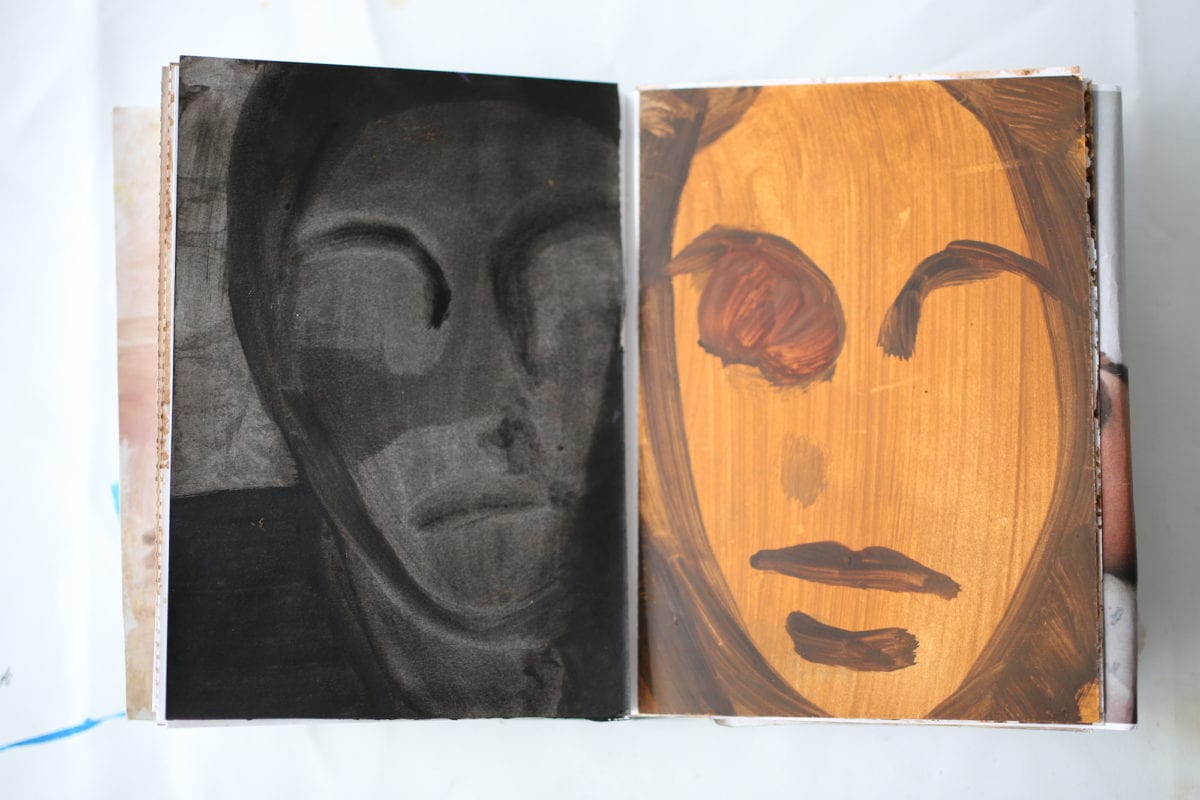

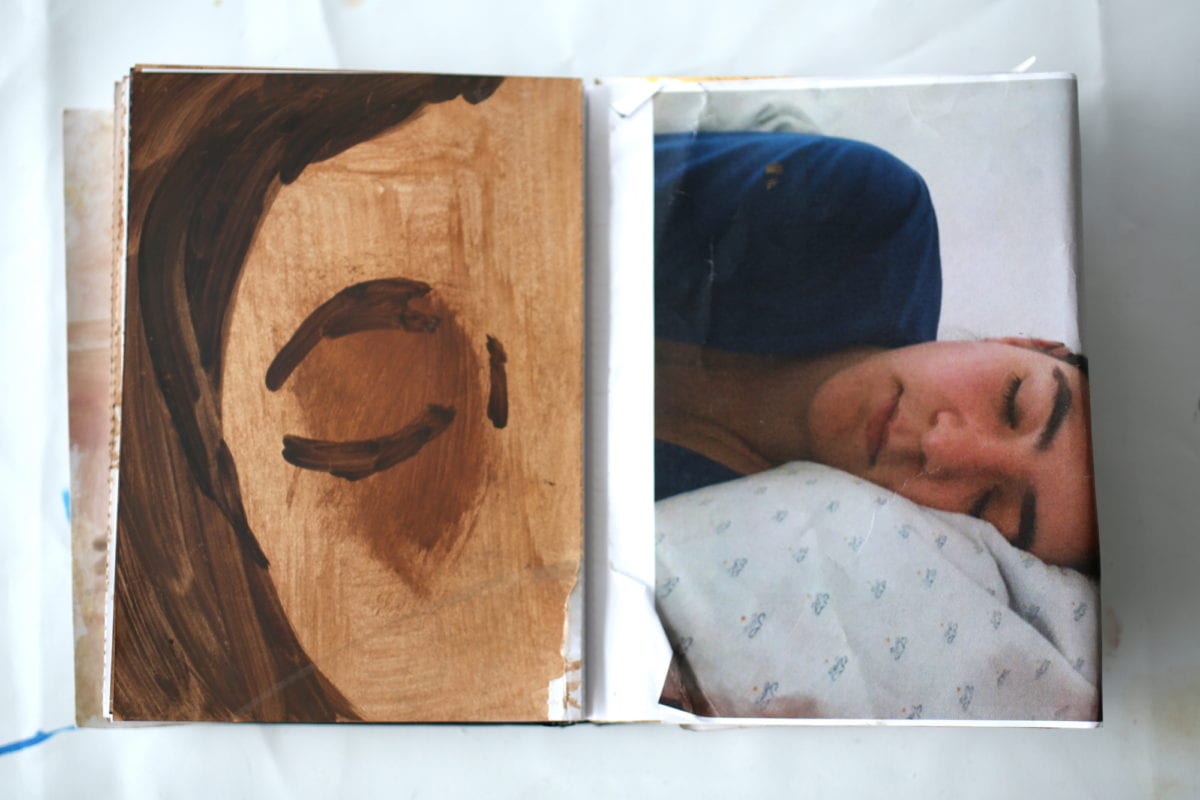

There are a lot of sleeping figures on the floor of Sikelela Owen’s Elephant Lab studio—not actual people, but the faces of friends, loved ones and acquaintances, painted from camera and iPhone images sent to the artist. Their faces are made up of a rich palette of browns and golden tones, with a few depicted in black-and-white. They are super-close-up, larger than life-size in some cases; their faces aren’t contained by the dimensions of the paper they are painted onto, and as the viewer it feels as though you are getting an intimate view into a private moment for each of the subjects.

“Even though I tend to work in very muted colours, I do think about colour a lot”

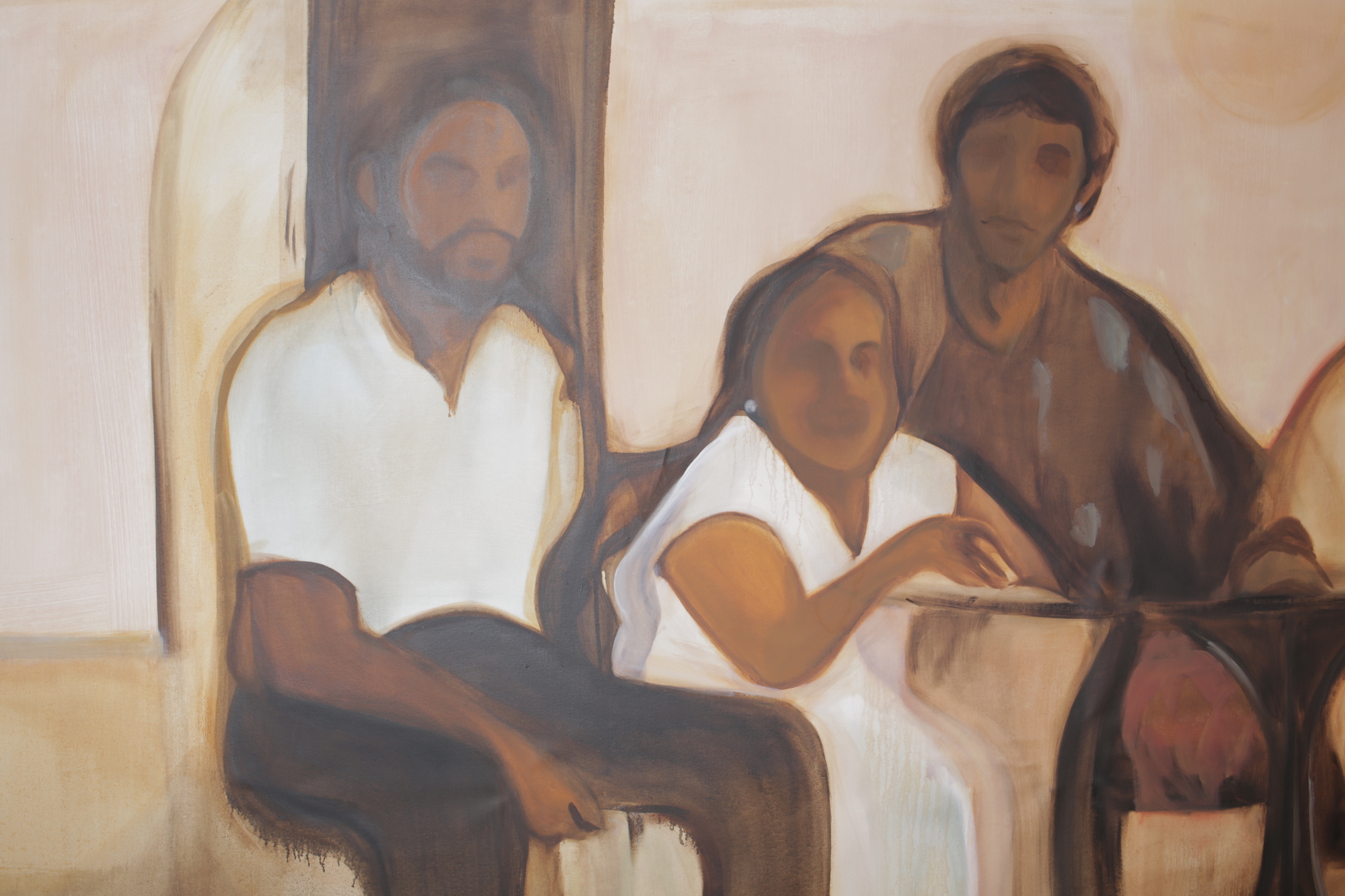

During her one-month residency, she has also painted a few large-scale works, one is inspired by a family photograph taken in Jamaica, another shows her late grandmother sitting proudly with a regal lean on the arm of her chair. I met Owen to discuss memory, family relationships and her sumptuous use of colour.

When you interviewed for the residency, you had quite a set idea of what you wanted to do on it. How has that developed while you’ve been here?

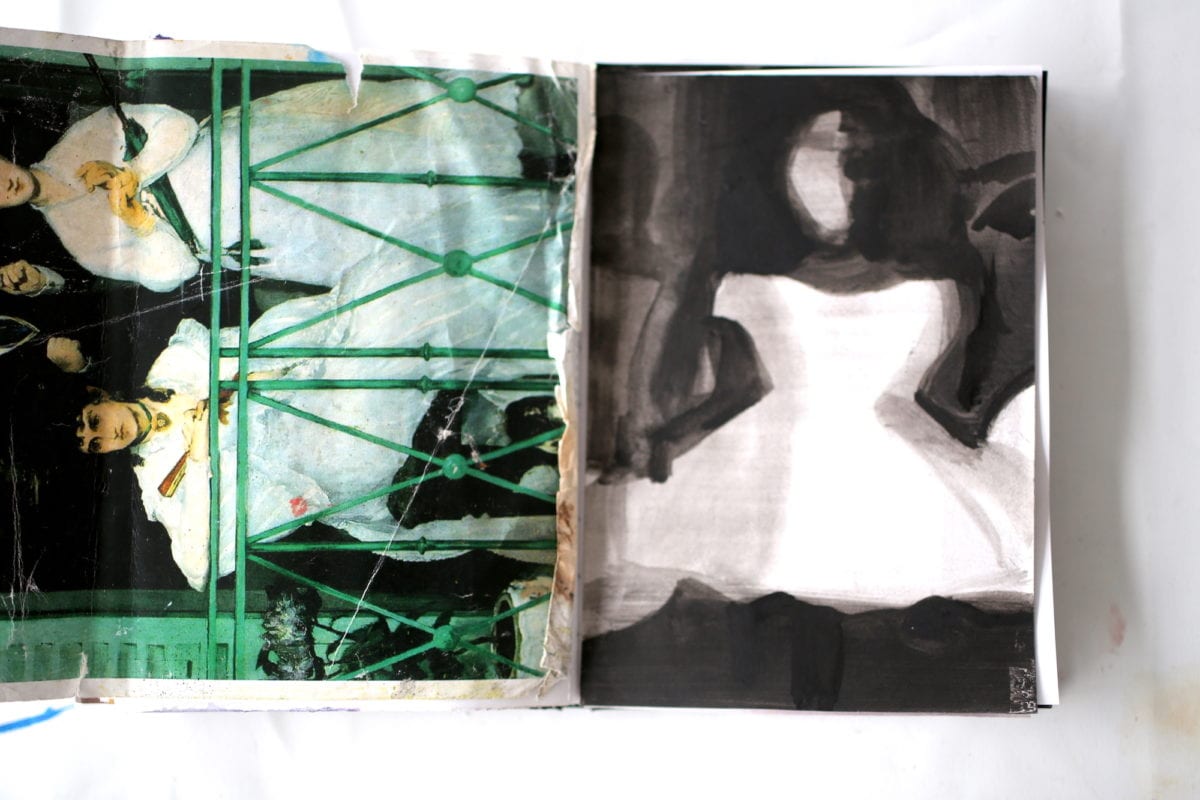

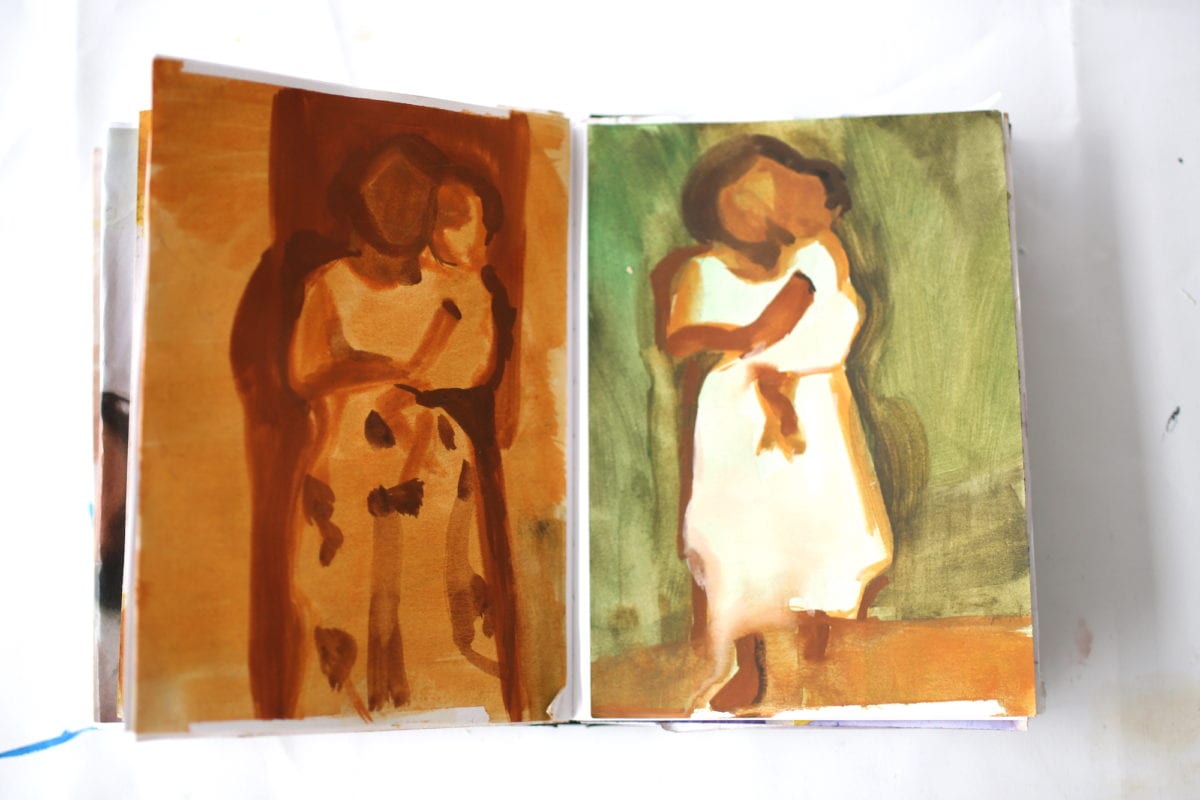

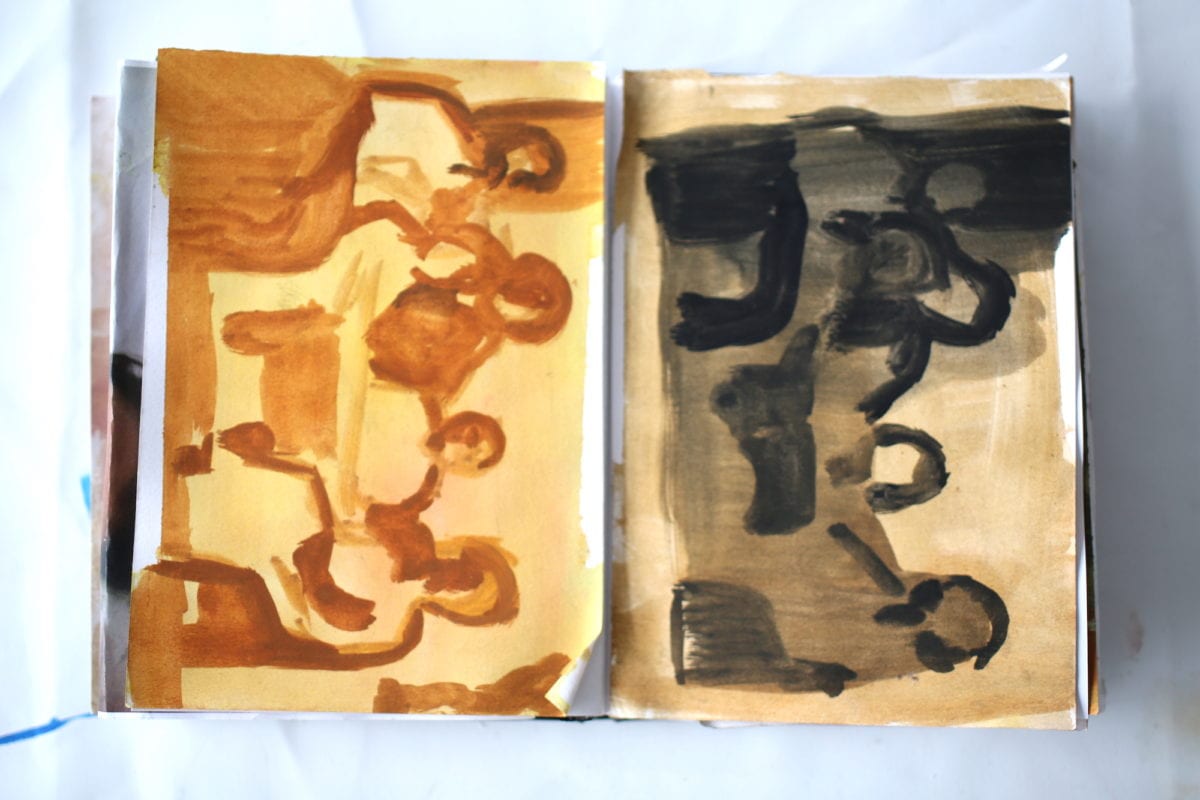

When I came into the interview I was thinking about memory and memorials. I’ve dedicated quite a lot of time to exploring that, with the living room painting and the sleeping portraits, but then I’ve also got really bogged down in material things. So the surfaces, looking at the colours and how the base colour changes the overall painting—like the greens bleeding through—and what it does to other colours. And I’ve been messing around with some mediums. It’s been really really interesting.

The colours are incredible that you’ve been working with.

Thank you. Yeah, I really love colour. I normally mix a lot of colours, I think most people do that—you don’t buy every single colour, but you buy a base palette and then you mix a lot of colours. Even though I tend to work in very muted colours, I do think about colour a lot.

Are all of the paintings you have created here from photographs?

Yes, and one drawing. Previously I went through this phase where I was just using black-and-white photos, then I got to think about colour more. But with these ones, because I’ve been getting them from different people and different sources, I have been using them as they are. I really like the richness of the colours. For the most part I work with black skin, so when I’m moving onto someone else’s skin, I’m trying to make sure it’s truthful. It’s really interesting how much colour is in people’s skin, it’s amazing.

I’m interested in the idea of individual identity in your work. Obviously many of your paintings are of people who you know, but as the viewer you can’t quite reach them, because their face is painted out or their eyes are closed.

I am always trying to decide how much I want the subject to engage with the viewer. [Seeing someone sleeping] is a very intimate thing, even with their eyes closed. Also, working from photography often the eyes and teeth are very highlighted, so making shifts in the painting sometimes means moving away from that. These are people who I know, but I suppose I want the works to be more accessible—it’s not important for the viewer to know what I know. So, I think there is something about leaving space for the viewer to engage with it, with regards to eyes and eye contact and big signifiers.

Although you make a lot of changes when translating an image from a source photograph onto the canvas, do you want the final works to have a photographic element?

I actually quite like some of the photographic lies. I was looking at Caravaggio’s work and all the dramatic lighting, which is similar to photographic images a lot of the time. I specifically deal with a lot of, what would be thought of as “crappy” photographs, because when things are bleached out, when the contrasts are just unreal, I think it gives me more to work with. I do draw from life sometimes, but because I often work from photographs, I have to double check, you know: that is how it really looks, but does it read real?

“You know your family, but you don’t really know them—there are so many things that you don’t know about people”

There’s also a temporariness to the poses in your paintings. Usually when a subject is posing for a painting, it tends to be slightly more formal, a pose that you can hold for ages and ages. In your works the people tend to be leaning in to have a look at the viewer (or original photographer) and it feels like more of a fleeting moment.

They are meant to be like moments. It’s very much… not movement, but the implication of a movement, and a moment, and snapshots. I’m very interested in narrative painting and narratives in cinema and all those bits where nothing’s really happening. I mean don’t get me wrong, I do tend to watch absolute crap cinema, so it’s not that I go around only watching only French things, but it’s the moments where they are just sitting on the couch that really interest me because it’s that sort of idea of pretend real, and what makes it believable and what doesn’t. It’s weird to me that the pose I see it at the National Gallery is very familiar—even the reclining figure, I then see someone trying to sell me something in Ikea with the same pose. Some of my images are taken from spaces like social media where people are often doing a very specific kind of pose.

Can you tell me a bit about the painting of your grandma that you’ve done?

The one-arm lean pose was all my grandmas. She’s queen bee of the family, so she looked like a bit of a don and she looks like the queen here and she looks very regal with her subject/son.

Do you feel like there’s something, not necessarily eerie, but unsettling in the way that the figures faces are slightly hidden from the viewer, almost as though there is something being shrouded?

I mean I do think that that one [of Owen’s grandmother] feels slightly different, because of the power pose, but it’s really hilarious because it is literally an old woman sitting in her house in Jamaica. She’s looking quite content, but I think with the big veil in the background, it creates a certain amount of distance, because the figure almost merges back into it. It is more like memory and memorial and the idea of loss, because the people in these images are no longer with us. I don’t think they are necessarily meant to be eerie but there is that notion of looking back.

Yes, and perhaps trying to sort of grasp something, trying to find that connection?

Exactly, that sort of processing. I got married last year, and I’m thinking about families and kids and stuff, and you think about those connections, like who were these people before I was in existence. Looking back and thinking about people as people. You know your family, but you don’t really know them—there are so many things that you don’t know about people. I’ve been to so many funerals, and it’s that weird thing where you hear the eulogy, and hear all these adventures of this person who you just took for granted because you would just go to their house and eat, and hang out.

And do you feel like it has changed the way you engage with your family and think about your family?

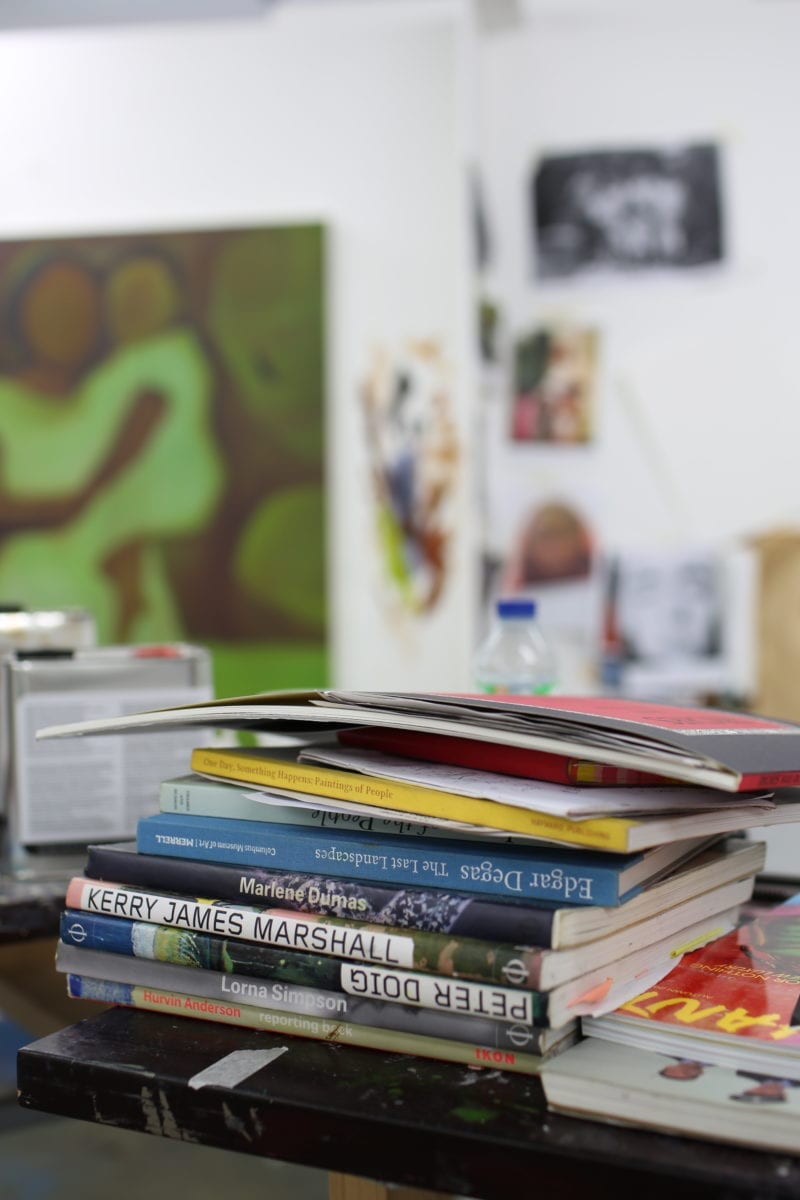

Engage with, probably not. I mean I’ve always had quite an honest relationship with my parents, even though I still learn stuff about my mum all the time. But I am forcing myself to have more conversations, because when I’m looking back I am guessing and thinking and using my experience of them, of the people who are no longer here to look at that. But I’m also having conversations with other artists, such as Marlene Dumas and Kerry James Marshall, so I’m having visual conversations as well as those ones, which is where I think the distance comes in because I don’t want it to be too much like “this is my life”.

Photographs by Louise Benson

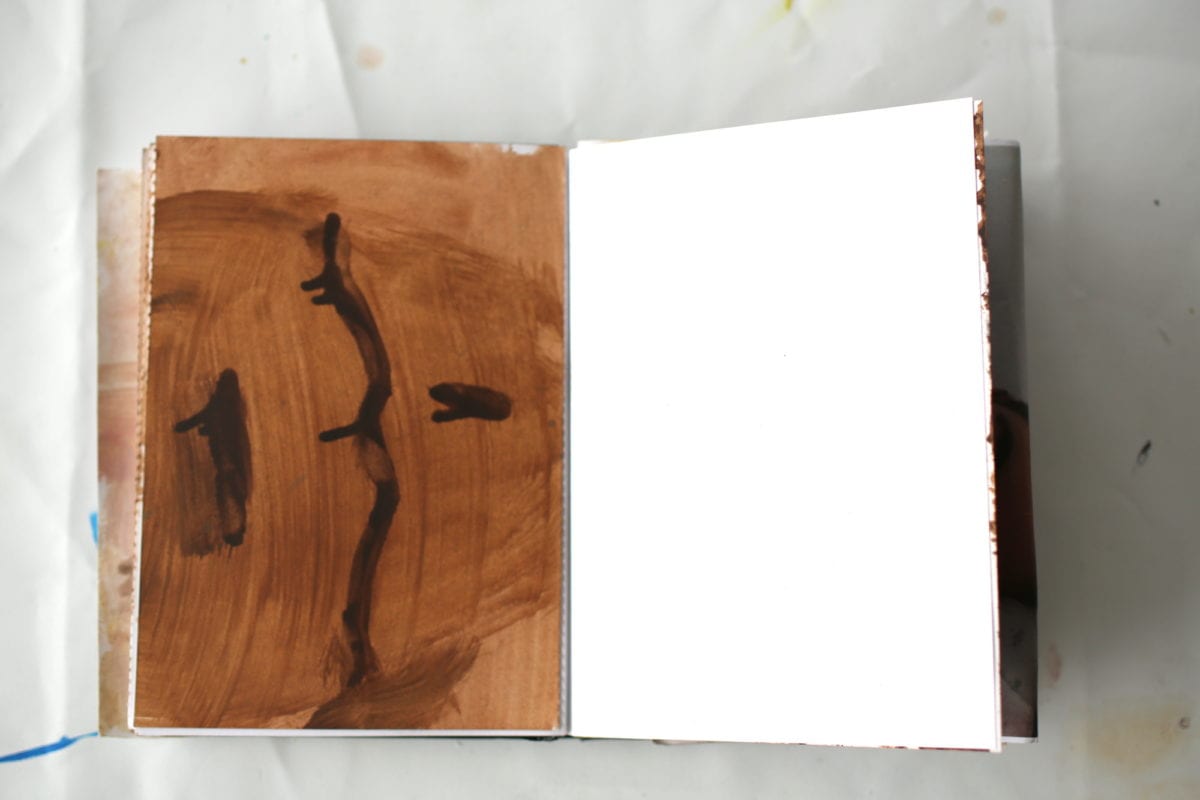

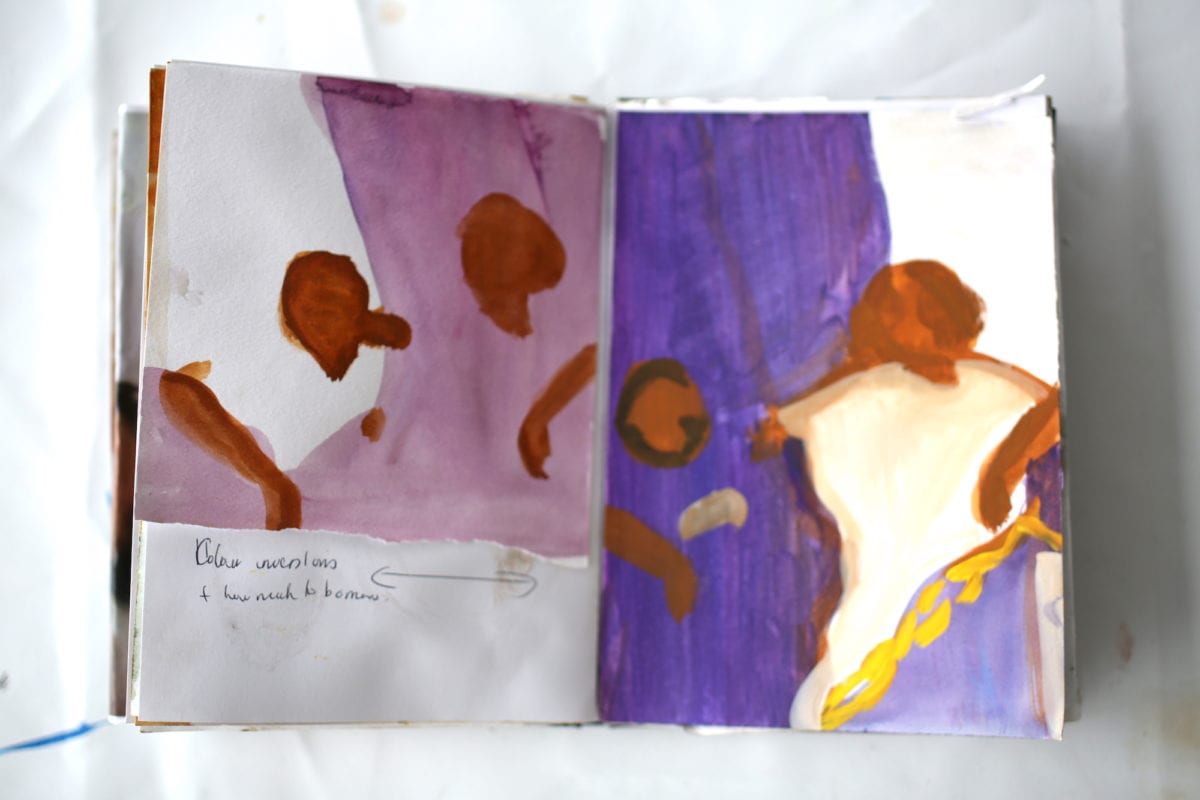

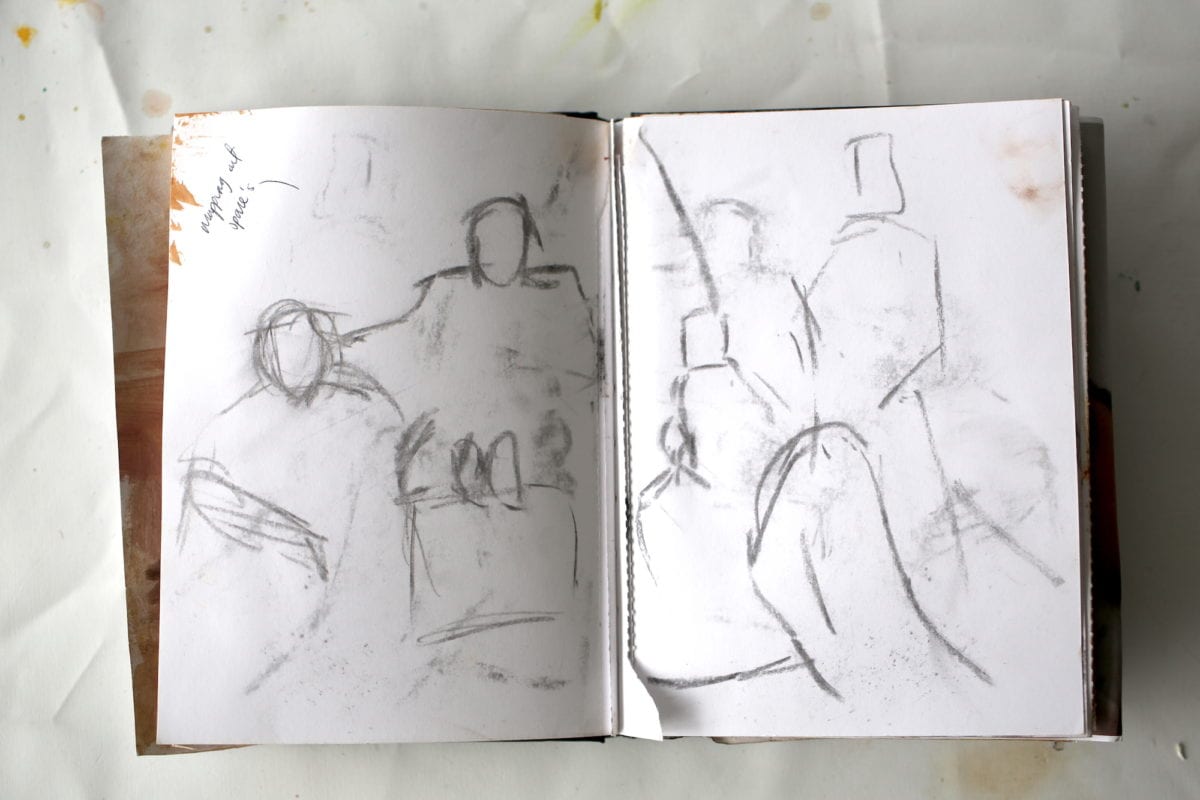

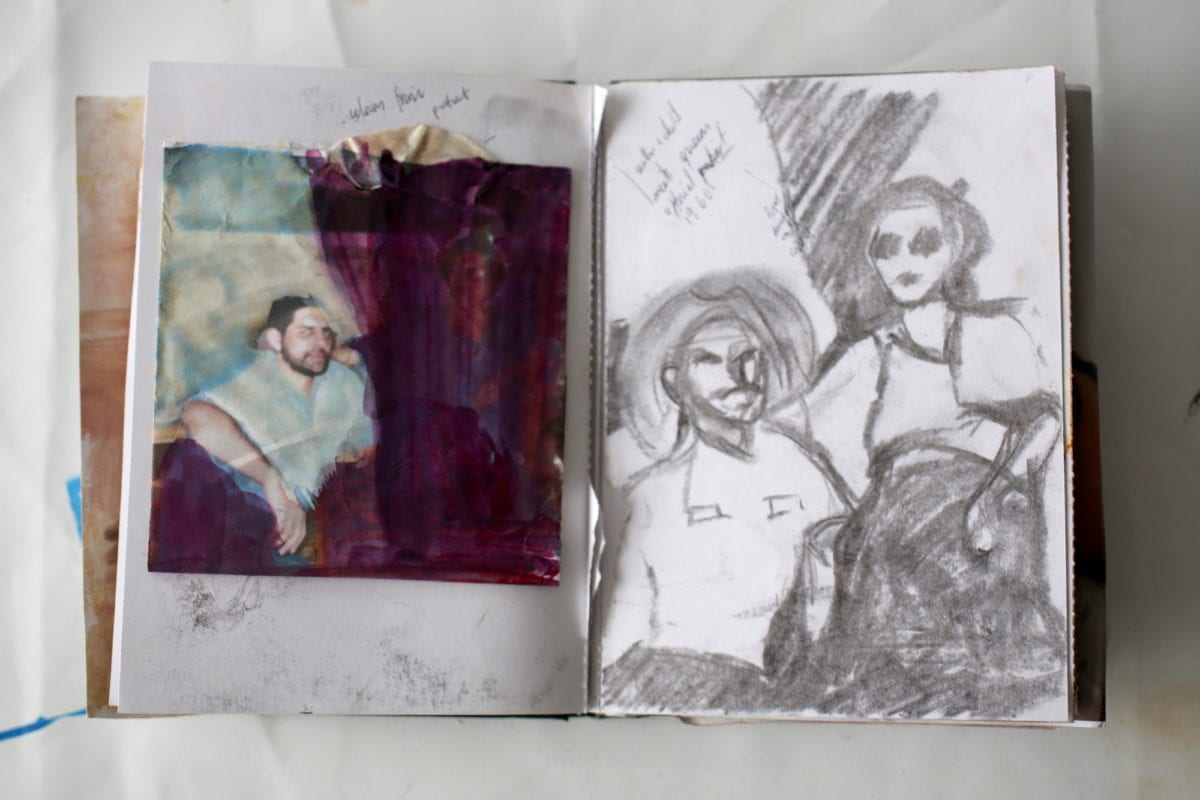

All artists-in-residence are invited to document their time at the Elephant Lab in a Winsor & Newton sketchbook, filling it with drawings, paint samples, odds-and-ends and other personal reflections. This is Sikelela Owen‘s.

Residencies at Elephant Lab

Practising artists are invited to make proposals for a one-month residency at Elephant Lab

APPLY NOW