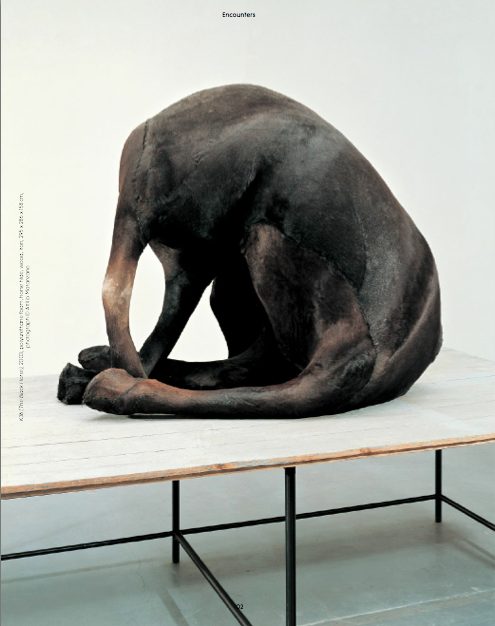

Unlike many of her contemporaries, Berlinde De Bruyckere‘s works do not require any contextualization or background knowledge to communicate their essential meaning to the casual viewer. They possess that old-fashioned Benjaminian ‘aura’. Inspired by masters of intensity like Lucas Cranach the Elder and Pier Paolo Pasolini, the Ghent-born sculptor conjures up visions of chilling beauty, twisted figures that stretch a tense cord between humanity and nature.

When I visit her in the former school where she and her husband – fellow artist Peter Buggenhout – both work and store their creations, De Bruyckere receives me in a room that is furnished with two sober tables (one wood, one black stone) and naturally lit through a glass ceiling. After we sit down at the sober stone table, on two heavy wooden chairs that demand an equally sober posture, she offers me some coffee. When I notice the cups don’t have handles and my hands have to deal with the heat directly, I can’t but think of De Bruyckere’s artworks.

I’ve read you grew up between a boarding school and your father’s butcher shop. Did those experiences shape the way you do art?

People always ask me about the boarding school, but the only thing I want to say about it is I was just five years old, it was normal for me. I had no other examples. When I wasn’t there I went to my grandmother’s place, which was immersed in nature, and that was always really beautiful to me. I liked being overwhelmed by it. As for becoming an artist, it was very lonely at school, so I had to draw to evade that atmosphere. It came quite naturally and that inspired me to continue. In that sense, I think boarding school was important because it forced me to find that way out and it made me stronger.

You’re often associated with Cranach and Bacon. I was thinking Schiele too…

My favourites are mostly video artists, rather than people from the contemporary art world. I get compared to Bacon a lot; they even call me a three-dimensional version of him. There is definitely a link between us, but I discovered him very late. The first time people pointed that out explicitly was in 2005 or 2006, in Düsseldorf, when I had an exhibition right in front of a Bacon show. If I had to find a connection I’d say the topic of the deformation of the body is definitely one, but also we both try to create a distance between the work and the visitor. He used this gold frame and glass that very often reflects you into the painting, while I use horse skin, or sheets, because those things remind people of something from their life. I think that’s a beautiful entry into the work, an invitation, but the beauty also provides distance, in the way Bacon does with the frame and the glass. People often tell me my works are about dead bodies, deformation, destruction, but on the other hand there is also a lot of hope and beauty. This is what I really want to show.

Let’s talk about the Biennale. Your show is curated by the writer J.M. Coetzee. How did the collaboration come about?

I’d known Coetzee’s work for a long time. We made a book together, We Are All Flesh. I asked him if I could take quotes from his work and put them in combination with details of my own pieces. They are excerpts from different books, so the way you read them sheds some light on the works and the evolution between them. Sometimes if you see an old piece after two years it means something completely different, because an artwork is so layered you need another chance to read it. It was the same with me and Coetzee’s writing. I gathered all the quotes, ordered them and sent him the selection. We started having an interesting conversation, and he said it would work better if I also used only details of my pieces, rather than full pictures.

And what about Venice?

I received the invitation to the Biennale last summer. It was very late, and since you have to find a curator yourself I started looking for someone in the contemporary art field. If I have to think of fruitful examples in terms of curatorial collaboration, the two main exhibitions that come to my mind are the one at Kunstmuseum Bern, where my work was in conversation with Pasolini and Cranach, and one at Arter, in Istanbul, where I worked with Selen Ansen as a curator. In that case it took two years to arrange everything, from finding the location, which was a historical building, to getting to know each other. For the Biennale we only had a couple of months, so having to find a curator put more stress on me than working in the studio. Since I am very much into Coetzee’s work I thought it was more logical to ask him to be the curator and continue our collaboration. He agreed.

How did your collaboration work?

I told him I didn’t want him to comment on the structure of the work, since he’s not so familiar with contemporary art, and that for me the meaning of curator is someone who feeds you, gives you inspiration, stays next to you, replies to your letters, who tries to put your project into words. Since the beginning it was clear that I wasn’t working on a museum exhibition, I really wanted to make something that forces you to take a position, rather than an idea deriving from the combination of different works. Just one work, one experience. Since it was something I couldn’t realize in my studio, there was also no need to have Coetzee here to show him the work. We made all the parts here, shipped them to Venice and assembled the installation in the pavilion itself.

Your most iconic works deal with the human figure, sometimes with animals. Why the tree this time?

I found the tree in France a couple of years ago, in one of my walks. I immediately fell in love with it, I couldn’t forget it. They did some restoration on a bridge, uprooted it and left it in a field. To me that felt so radical, because when a tree is cut down they make something new with it, but seeing it there, without its roots, made me think of those people who find themselves uprooted from their country, without a second chance.

Which makes sense in relation to Coetzee’s work…

Yes, exactly.

You mentioned video art. Who inspires you in terms of the moving image, apart from Pasolini?

It’s more a sort of familiarity. I like Steve McQueen, Anri Sala and Marijke van Warmerdam – she’s from Holland. But there are many. It’s not that there are no sculptures that inspire me, maybe I like looking at artists that use another medium. In 2014 I’ll have a solo show here in Ghent, at S.M.A.K. The museum is so big that I thought it would be a good idea not to present only pieces of mine. They’re demanding for the public, showing too many could be overkill. I told the director I’d like to invite other artists of my choice to combine their work with mine, maybe not in the same space. For example, Teresa Margolles…

I can see that working.

Another one I have in mind is Wolfgang Tillmans. I think the medium is very important.

Have you always used wax?

I have for about 15 years. I was looking for a way to recreate the feel of human skin, the way you see it at Madame Tussaud’s. I work with it, using different layers, like a painter, applying different colours to make wounds, for example. It gives me a lot of freedom, and it’s not making a sculpture out of something; instead of taking things away, I’m putting things together. That’s why furniture is so important in my work: those objects are coming from another history and I like to build new work on top of that. When I use vitrines I construct the work inside them.

How do you shape your figures?

For one body I have to build four parts in four different moulds. Every layer is about two millimetres, so it needs about 20 layers. It’s like making a watercolour drawing, with the colours melting into each other. That’s the surface you see. After that we continue to strengthen specific parts and make a thicker layer, between one and two centimetres, just in white wax. It’s warm and, once you take it out of the mould, you can shape it. We do the same with all the parts, then we open them up to put a solid structure in epoxy and iron inside, otherwise we wouldn’t be able to move them without breaking the wax.

Many artists are now becoming designers, architects, social engineers. They’re more and more detached from the artwork. Your work speaks by itself, it doesn’t need to be explained. What’s the feedback from the art environment and how has that changed over time?

It’s very interesting. Last month I was in Venice for all those special occasions, and I was very surprised to see people who I had never met coming up to me and hugging me. They were thanking me for doing my work, they said it’s heartbreaking. I was very touched that my piece could do that, it was very hard to put it together in such a short time and that proved it was worth suffering so much for it. On the other hand, when I sat at dinners with collectors and other artists I felt so lonely. I’m so far away from the market. I never worked on my career. But, even though there’s a big gap between what’s going on in the art world and me, a lot of people believe in my work. When I was first at the Biennale, in 2003, my art wasn’t very known, but now that I work with Hauser & Wirth and Galleria Continua my pieces are exhibited worldwide. I still need the distance to be on my own in my studio, though. I was always lucky that I could work with good people that allowed me to do that.

So you’ve never lived in international art cities like New York or London?

No, I always stayed in Ghent. Now we’re moving to another house in the city, but we’re keeping the studio and the house because I normally work with four assistants and we eat here and all. We need the house as a place to have a normal studio situation, to make it more like a place to work with family and not just with employees.

Are there any directions in which you’d like to expand your work?

I’ve done something in relation to architecture, and now I’d like to work with a dance performer. I’ve had some experience with several dancers from a company here in Ghent, directed by Alain Platel, the choreographer. The dancers are not just models anymore, like it was in the beginning, when I was more interested in the iconography of the body. Initially they were just flattered I was asking them, but they were not interested in contemporary art or in my work. Then I started becoming friends with them and I did a small performance with Romeu Luna. I invited him to move with a couple of antlers on and he did different poses, just for a photo shoot. The second day he didn’t want to do that anymore, he wanted to dance with the antlers. He did it for us only, but we didn’t record it, we just took pictures. It was so strong, though, that I asked him to do it again on stage, at a book presentation in London. I’d really love to do more of this, to work together on something similar.

What do your kids think about your work? Does it scare them?

They grew up with it, it’s normal for them. Last night they were watching The Lord of the Rings again, and there is that figure, Shmelly…

Smeagol?

Smeagol. And my son, who’s 15, when he saw it for the first time, he said: ‘Mama, they used one of your sculptures to make Smeagol!’

We actually meet her son on the way back to the entrance, after visiting the former classrooms where she and her assistants mould wax every day (and cool it down with regular hairdryers, which makes me smile). After she tells him something in Dutch, referring to my earlier question, he goes: ‘Scared? Nah.’ And walks away.