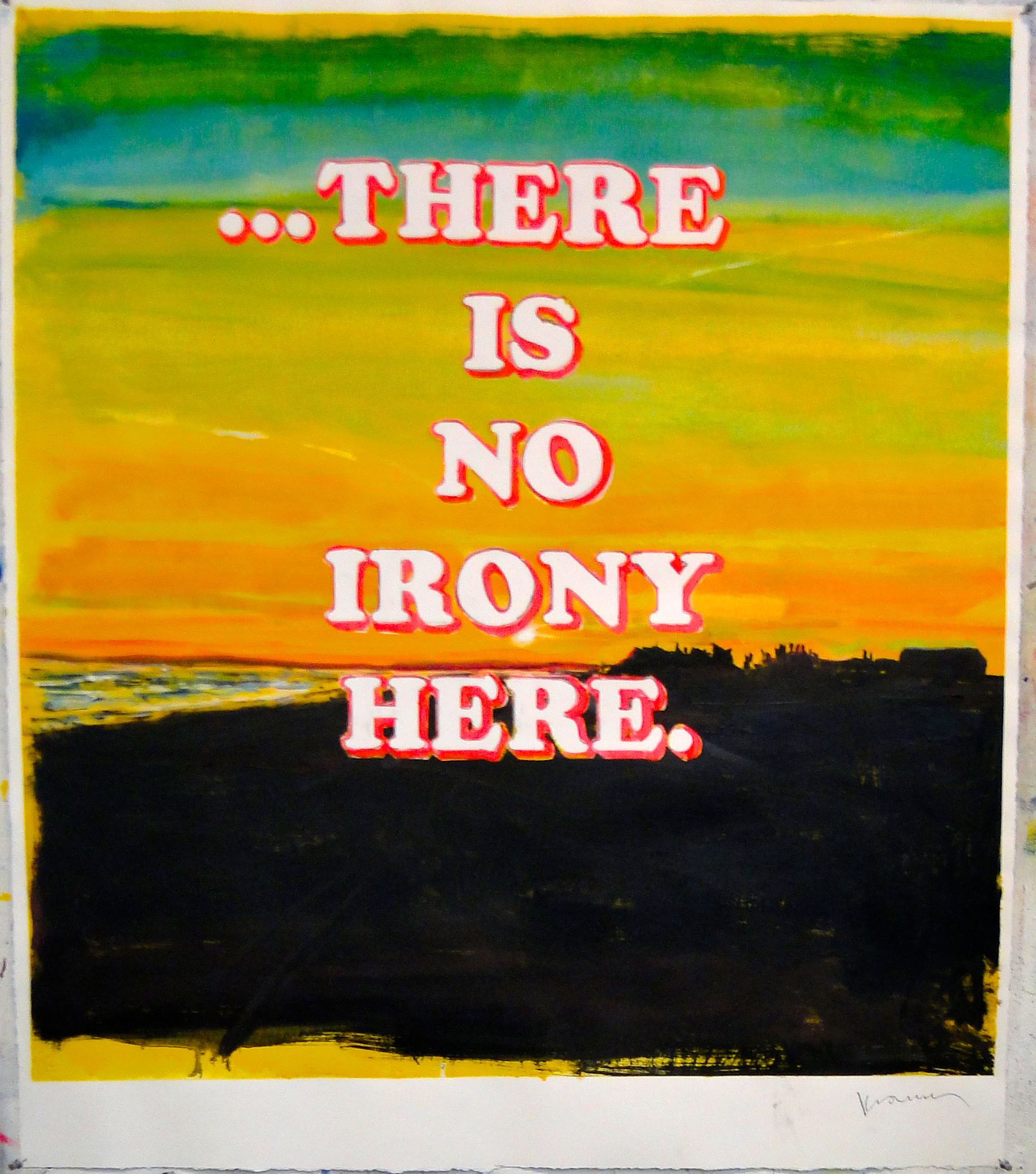

The words, “There’s No Irony Here”, have been pasted onto the vitrine of French fashion house Celine’s rue Duphot storefront in Paris. The statement is the work of American artist David Kramer. It’s funny because it’s not true; there is a grand irony to sardonic political aphorisms being slapped on a straw bag and put up for sale.

Hedi Slimane, the creative director of Celine, invited Kramer to collaborate with the brand in 2019. The resulting collection of wallets, bags, jumpers and shoes is currently in stores. The artist is in joyous disbelief: “The fashion industry isn’t known for humour

and self deprecation,” he says, gleefully. “Of course I’d heard of Celine before; the great irony of it as a brand is that they advertise everywhere. In New York they advertise on bus stops, which is hilarious because no one taking the bus is buying Celine. But it has this street cred, it has a reputation for being a sexy brand.”

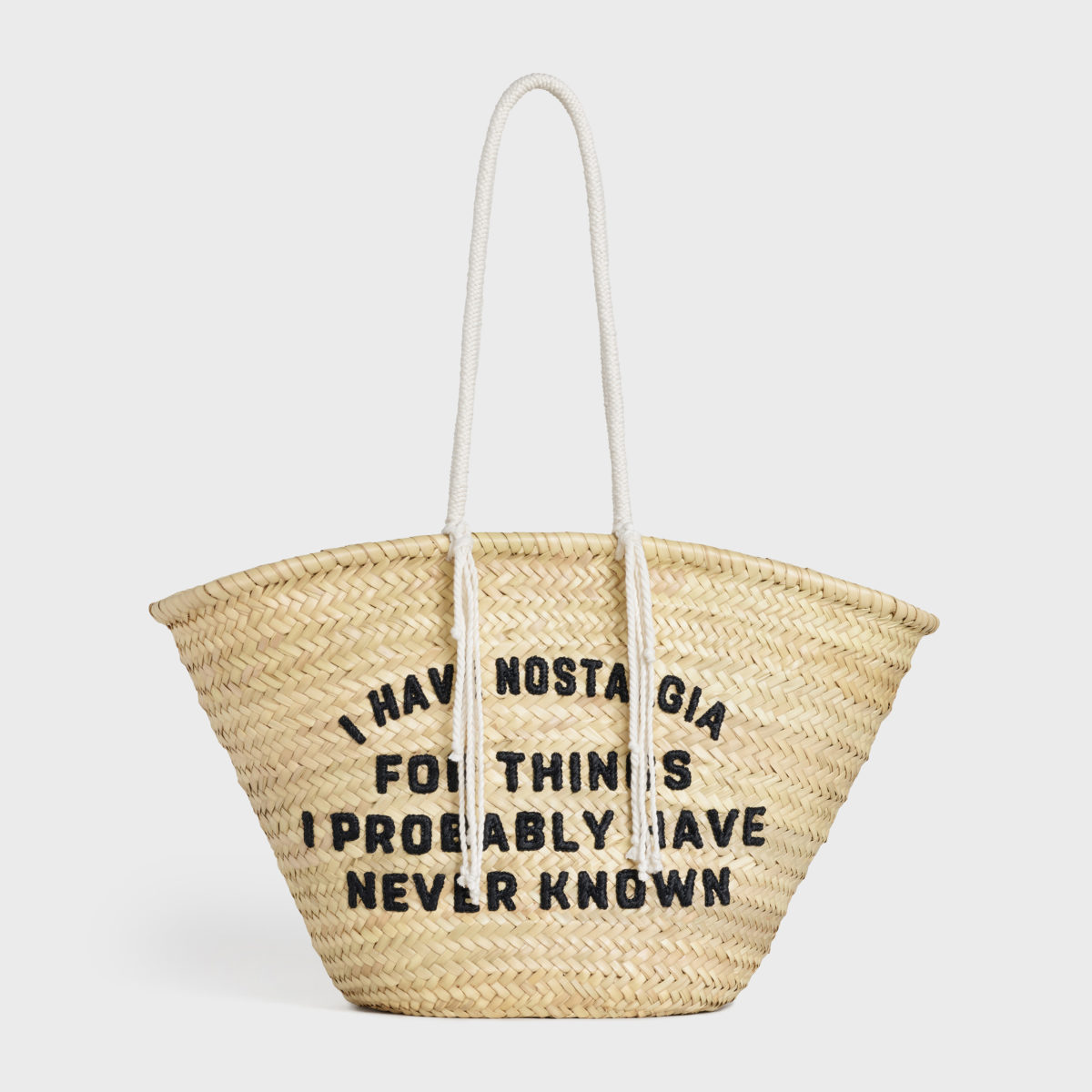

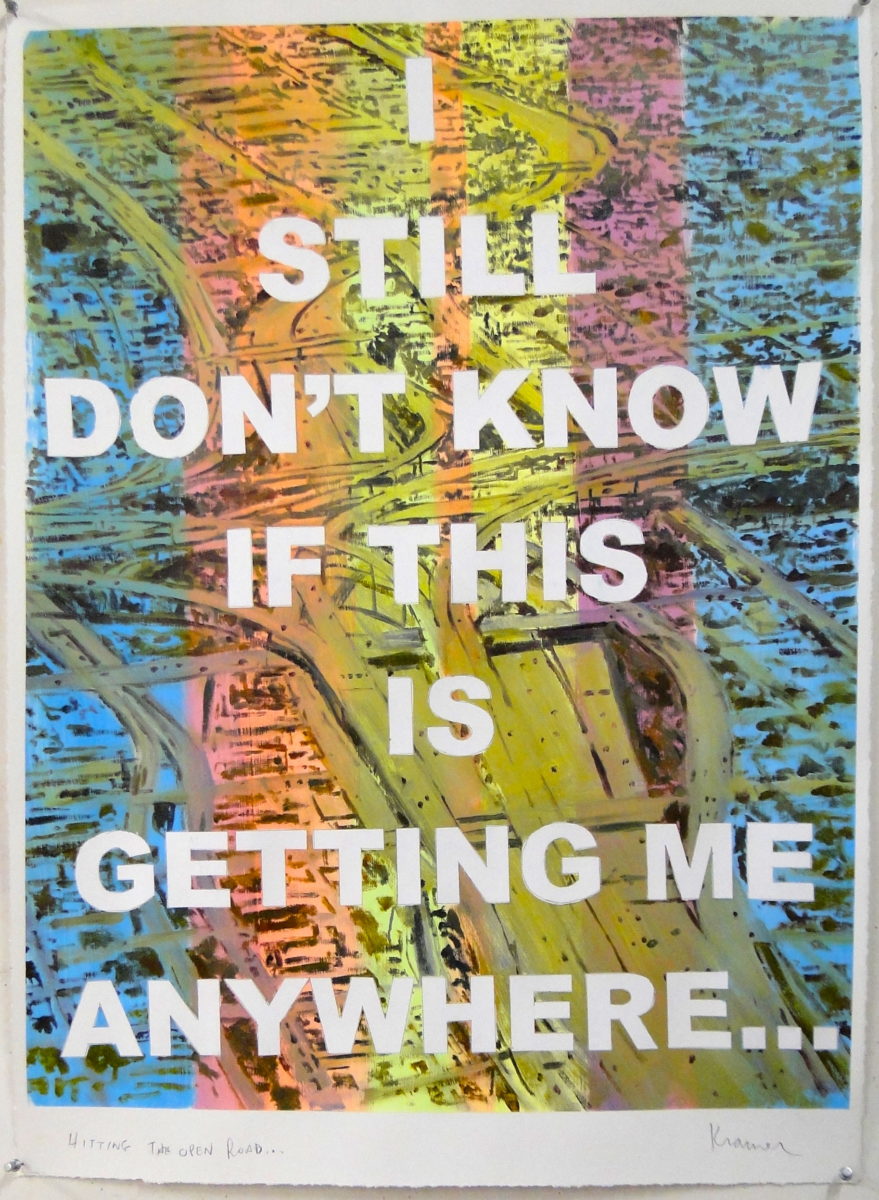

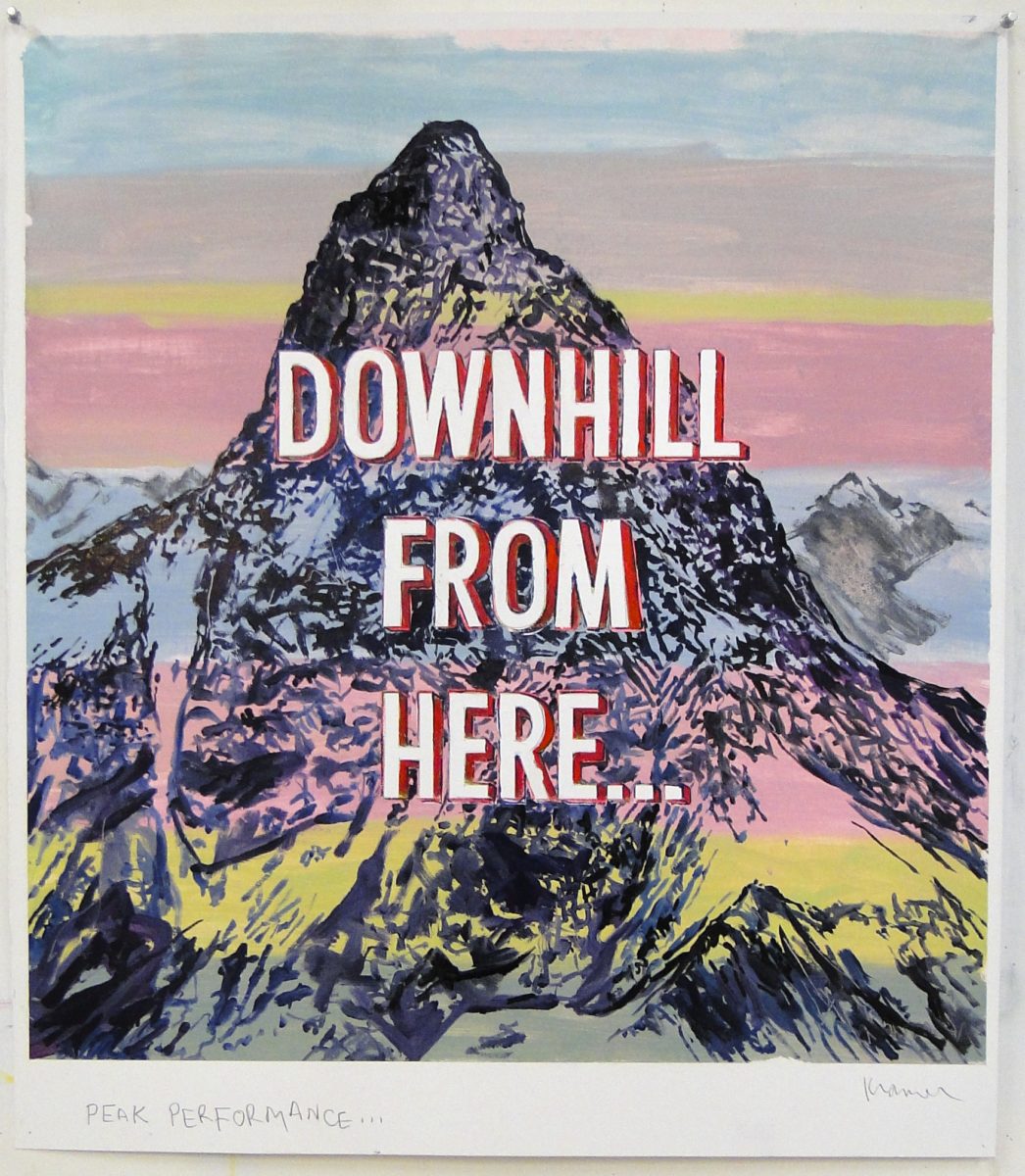

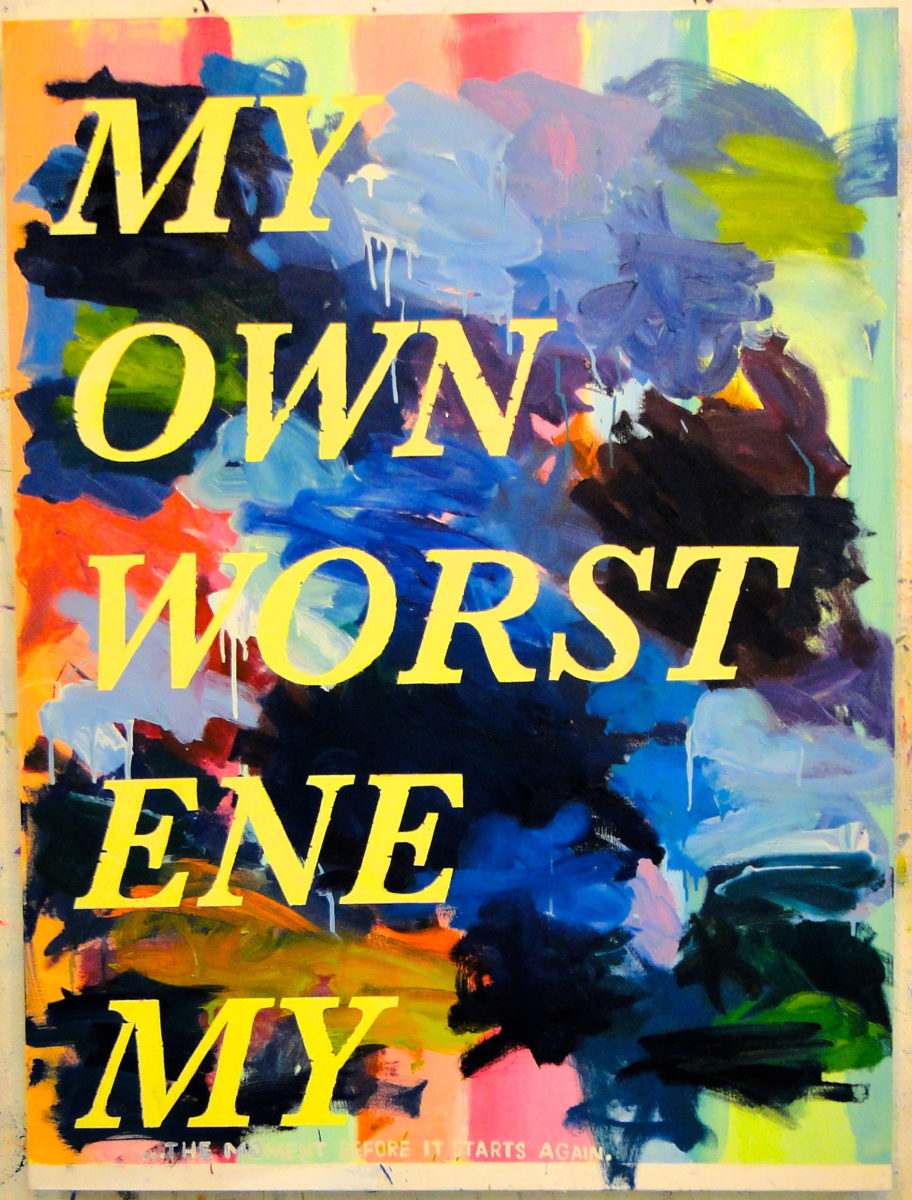

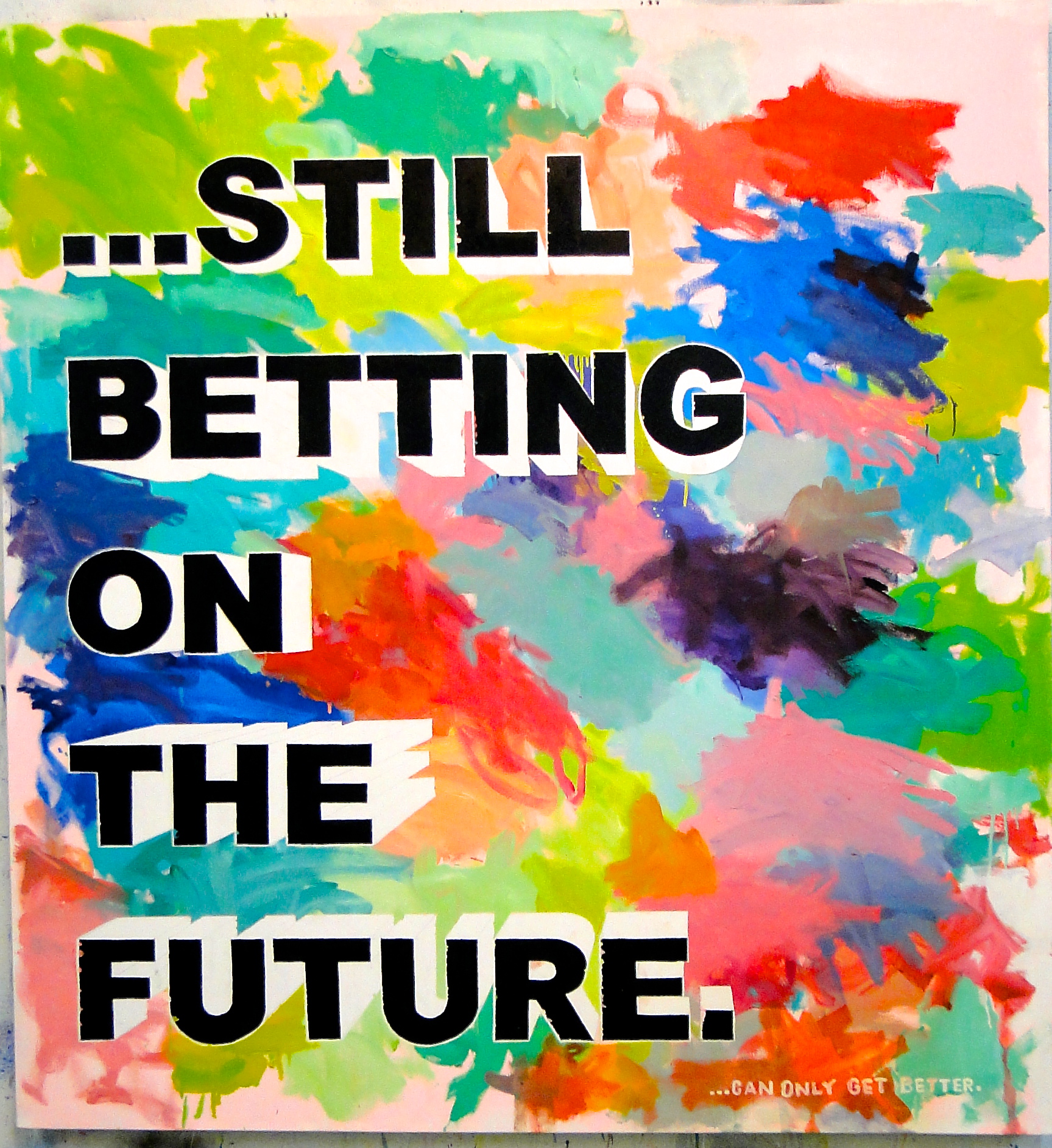

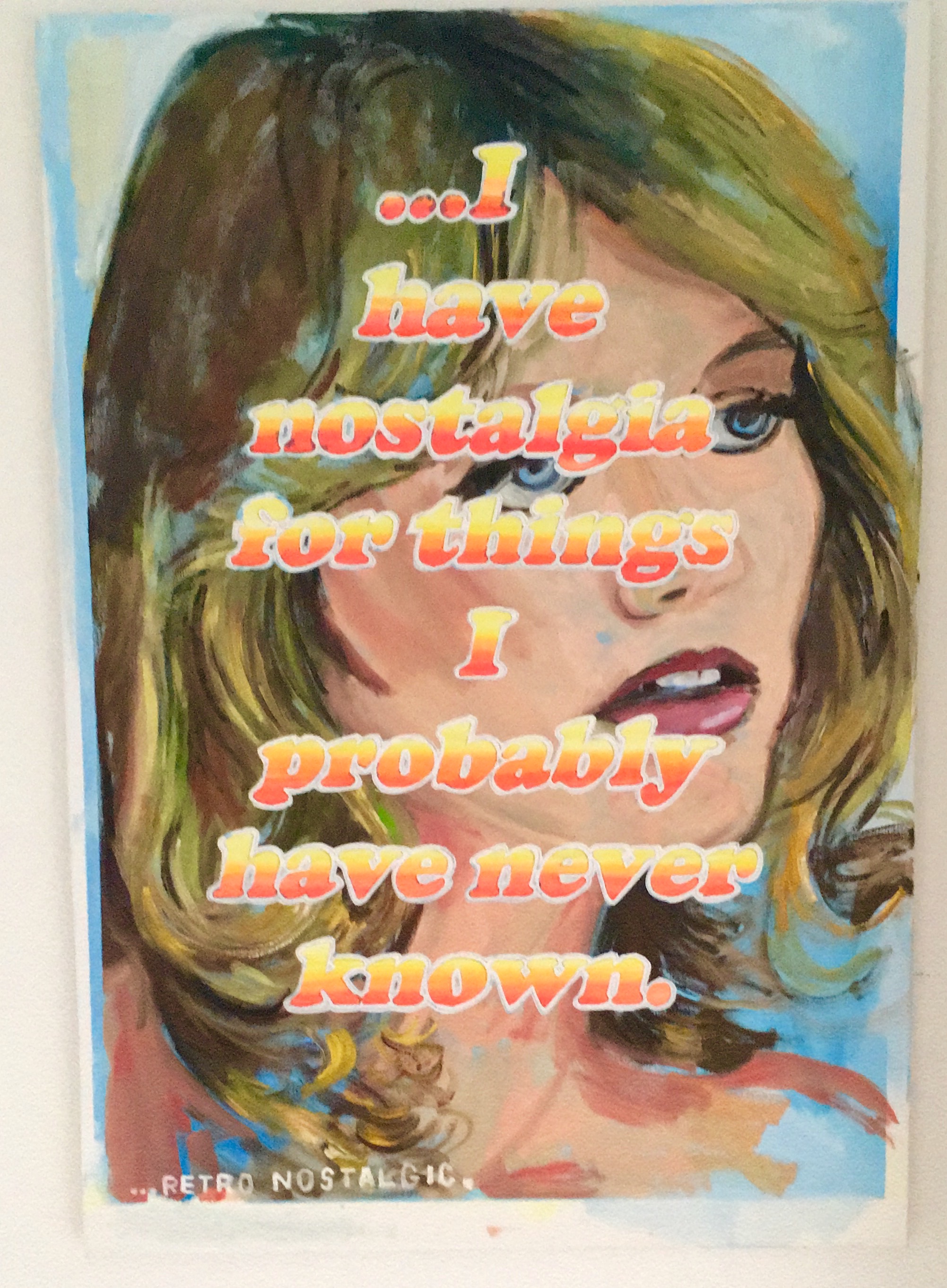

Kramer describes his work as “handmade memes”, painted sunsets or scenes-de-vie that take cues from Instagram trends and 1970s advertising, overlaid with text: “I have nostalgia for things I’ve probably never known”, reads one, “Vaguely Aspirational”, says another. Early on in his career he made process-oriented works with long-winded titles to match, and the realization of the central importance of text to his practice came only when a curator told him flatly these titles were insane. And so the titles became interior to the work: “I became a text-based artist,” he says. “I hate the term, because I’m more of a storyteller; the text is the thing for text-based artists, but for me the text is applied to the thing.”

“When Trump got elected, my phone wouldn’t stop ringing with people telling me I’d predicted it”

It is often the case that in the heavily coded worlds of high fashion and institutional art, audiences don’t know when they’re allowed to laugh. In the case of Kramer, the didactic nature of his slogans gives viewers permission to find it funny. “What I see as humour is not a snarky comment,” says Kramer, “but satire.” The artist spent a childhood on the suburban fringes of New York City in New Rochelle. He would reproduce the images printed in publications such as LIFE magazine or Playboy, imagining a glossy future life informed by the adverts that filled their pages. “I thought that was what adulthood looked like. But then I grew up and moved to the city; I was poor and there was an AIDS crisis and New York was crumbling; there was a crack epidemic. It’s interesting, the point of convergence between what you expect and what you get.”

The artist’s work has long satirized the American Dream. “When Trump got elected, my phone wouldn’t stop ringing with people telling me I’d predicted it. I was like, ‘Oh God, no.’” Kramer admits his work has seen far greater success in Canada and in Europe than in America itself however. “I grew up in New Rochelle, down the street from me there was a country club that didn’t allow Jews to join, and I always felt like an outsider looking over the fence. My work has always been about this particular perspective, and I think this appeals to these audiences, to Europe looking across the Atlantic, or Canada across the border. But for Americans there is no distance.”

The collaboration with Celine is further proof of Kramer’s appeal to French sensibilities, as well as the flirtation with Americana iconography that the French fashion world entertains. “I think it works in France because there is such a keen love-hate relationship with America,” says Kramer. “All the French people I speak to want to move to LA, with the car, the sunglasses, the palm trees.”

When Celine reached out to the artist to collaborate, they didn’t contact his Paris gallery, Laurent Godin, but instead contacted Long Sharp Gallery in Indianapolis. “The women who run it, they’re great, they know all about Celine, they saw it and were like, this is a total scam, it can’t be real, don’t give them your bank details!” But Kramer followed up the request and a few months down the line found his work proudly displayed on the catwalk in Paris. Four other international artists have also worked on the collection: Zach Bruder, Carlos Valencia, Darby Milbrath and André Butzer.

“I don’t want to sound grotesque; my work was always about this failure to live up to the dream”

“It’s not like we were sat up late at night drinking beer and sharing pizza and hammering out the last line, but there was a nice back-and-forth,” says Kramer of the collaborative process. He has great admiration for the fashion world, who have welcomed him in, adulating the speed, efficiency, press coverage and potential for “discovering” artists. “I love being an artist but it is a solitary pursuit, and it’s a very different experience to be here, around people ready to take on any number of tasks.”

We muse on the experience of working as part of a team, as well as often having one foot out of the creative industries we operate in. “For years I worked as a painter decorator to subsidize my career,” says Kramer. “In my forties I left that behind because I got really busy with my career as an artist. I never had business cards; my way of working had always been that people would call me when they needed me. But I was busy all the time so they stopped calling because they thought I wouldn’t be available. It was kind of true, but not true. The point is, though, that the stories I would tell in my performances were often about my carpentry work; I’d always be learning something, or taking things from my day job into the studio. I think it’s important to have a way of externalizing your practice.”

I suggest the collaboration is a new way of having something outside to his artwork. “I don’t want to sound grotesque; my work was always about this failure to live up to the dream,” he responds. “But its hard to complain when the fashion world are inviting you in.”